And we are here as on a darkling plain

Swept with confused alarms of struggle and flight,

Where ignorant armies clash by night.

Mathew Arnold, Dover Beach

We called 2024 a “year of everything, everywhere, all at once”, and it earned the name. Crises collided, news arrived faster than we could process it, and the world seemed to exist in a state of constant shock. 2025 did not bring relief. Instead, the chaos began to settle. Wars dragged on, political divides hardened, social tensions deepened, and technology reshaped how we saw and understood it all.

It was the year the world stopped exploding in real time and started being what it had already become: messy, uneven, morally complicated, and stubbornly persistent. A year, indeed, in a world of echoes, refrains and unfinished business. And we spent the year watching power bargain brazenly in plain sight, trying to describe what was happening while it unfolded around us.

From Gaza to Ukraine, Sudan to Syria, from America’s self-inflicted fracture to Australia’s sudden wake-up call on Bondi Bondi, 2025 forced a reckoning: the world did not pause, but it did sort itself – deciding what we would notice, what we would ignore, and what we would learn to live with. Alongside human crises came the continuing advance of AI and chatbots, and the dominion of the algorithms that now govern attention, proving that disruption can be structural as well as geopolitical.

Gaza: War, Then “Ceasefire”

The war in Gaza dominated the year internationally and here in Australia, even as attention ebbed and flowed. Military operations continued for months, followed eventually by a “ceasefire” – a word doing far more work than it should or even justified. Fighting paused, hostages living and dead were returned and prisoners released, but the devastation remained: tens of thousands dead, cities demolished, humanitarian catastrophe unresolved. And the causes of the consequences standing still amidst the ruins and the rubble.

Western governments continued to back Israel while expressing concern for civilians, a contradiction that grew harder to defend, while street protests and online anger seethed all across the world. At the same time, antisemitism surged globally, often hiding behind the language of anti-Zionism. Two realities existed together, and too many people insisted on choosing only one.

By the end of the year, the war had not been resolved – merely frozen. Trust in Western moral leadership had been badly damaged, and Israelis and Palestinians remain in bitter limbo.

See Gaza sunrise or false dawn? Spectacle or Strategy

Iran, Israel and America’s bunker busters

Long-simmering tensions between Israel and Iran spilled into open conflict. What had once been indirect – proxies, cyberattacks, covert strikes – became visible. A brief but destructive war of missile exchanges ended with the United States asserting ordinance, deterrence and control.

The episode was brief but telling. It showed that America still reaches for its guns quickly, even as it struggles to define long-term goals. Another line was crossed, then quickly absorbed into the background of “normal” geopolitics.

Russia, Ukraine and Trump’s “Peace”

Ukraine entered 2025 mired in stalemate. Front lines barely moved. Casualties continued to mount. Western support held, but with clear signs of fatigue. And Donald Trump’s re-emergence reshaped the conversation. His promise to deliver instant “peace” reframed the war not as a question of justice or sovereignty, but of exhaustion. Peace was no longer about what Ukraine deserved, but about what the world was tired of sustaining and what the “art of the deal” could deliver.

The war didn’t end. It simply became something many wanted to stop thinking about. Not Ukraine and Russia, but. The carnage continues.

Donald Trump’s one-way crush on Vladimir gave us the one of the+most cringeworthy moments in global politics – Trump greeting the Russian president in Alaska: As the US president rolled out the red carpet for the world’s most dangerous autocrat, Russia’s attack on Ukraine accelerated. Trump got precisely nothing out of the meeting, except for the chance to hang out with a gangster he so obviously admires and of whom he is embarrassingly in awe.

Syria: Free, but stranded at the crossroads

A year after Assad’s fall, Syria remained unstable and unresolved. The regime was gone, but the future was unclear. Old sectarian tensions resurfaced, often in bloodshed, new power struggles emerged, powerful neighbours staked claims and justice for past crimes remained distant.

Syria in 2025 was neither a success story nor a collapse – but suspended between heaven and hell, a country trying to exist after catastrophe with the rest of the world largely moving on.

See Between heaven and hell … Syria at the Crossroads

Sudan: what genocide actually looks like

Sudan’s civil war continued with little international attention. Mass killing, ethnic cleansing, famine, and displacement unfolded slowly and relentlessly. This was genocide without spectacle. No clear narrative. No sustained outrage. It showed how mass atrocity can now occur not in secrecy, but in plain sight – and still be ignored.

see The most nihilistic war ever …Sudan’s waking nightmare

America: a country divided against itself

The United States spent 2025 deeply divided, with no sign of healing. Pew Research polling showed that seven out of ten republicans think that the opposite side is immoral while six of ten democrats thinks the same of their rivals.

Trump’s return to power sharpened those divisions. His administration governed aggressively: mass deportations, punitive tariffs, the dismantling of foreign aid, political retribution, and pressure on democratic institutions. The country looked inward and outward at the same time – less cooperative, more transactional, more openly nationalist. Democratic norms eroded not overnight, but through constant stress and disregard. With three years still to run and the tell-tale midterms approaching, allies and cronies are adjusting, bickering rivals are taking notes, and uncertainty has become the defining feature of American leadership. Meanwhile, #47 is slapping his name on everything he can christen, from bitcoins to battleships.

See, for light relief, Danger Angel … the ballad of Laura Loomer

Monroe Redux: the return of “the Ugly American”

US foreign policy took on a blunt, old-fashioned tone. Pressure on Canada and Mexico increased. Talk of annexing Greenland resurfaced. Venezuela, caught in the maw of Yanqui bullying and bluster, waits nervously for Washington’s next move. The administration promised imminent land operations – and then bombed Nigeria! The revival of the old Monroe Doctrine felt, as baseball wizz Yogi Berra once remarked, like déjà vu all over again, not as strategy, but as instinct. Influence asserted, consultation discarded. The “ugly American” was back, and unapologetic.

See Tales of Yankee power … Why Venezuela, and why now?

Europe at a inflection point

Europe in 2025 didn’t collapse, as many pundits suggested it might, but it shifted. Far-right ideas gained ground even where far-right parties didn’t win and remained, for now, on the fringes albeit closer to electoral success. Borders tightened; policies hardened; street protests proliferated – against immigration and against Israel, Support for Ukraine continued, but cautiously. The continent stood at a crossroads: still committed to liberal values in theory, but increasingly selective in practice.

Uncle Sam’s cold-shoulder

Rumbling away in the background throughout year was the quiet but cumulative alienation of America’s allies. Not with a single rupture, but through a thousand small slights. transactional diplomacy dressed up as realism, alliances treated as invoices rather than covenants, multilateralism dismissed as weakness. Europe learned that security guarantees come with a mood swing; the Middle East heard policy announced via spectacle; Asia watched reassurance coexist uneasily with unpredictability.

The new dispensation was illustrated by the Trump National Security Strategy. It is at once candid and contradictory: it outlines a narrower, realist vision of American interests, emphasising sovereignty, burden-sharing, industrial renewal, and strategic clarity, yet it is riddled with silences, evasions, and tensions between rhetoric and likely action. Allies are scolded for weakness while the document avoids naming Russia’s aggression, underplays China, and projects American cultural anxieties onto Europe. These contradictions expose both strategic incoherence and the limits of paper doctrine against presidential temperament, leaving Europe facing an irreversible rupture in trust and revealing a strategy as much about America’s insecurities as its actual global posture.

The post-WW2 order has not so much been dismantled as shrugged at, and indeed, shrugged off. Trust eroded not because the United States has withdrawn from the world, but because it has remained present without being reliable, and presumed itself to be in charge. Power, exercised loudly but inconsistently, has discovered an old truth: allies can endure disagreement, but they struggle with contempt.

Australia in 2025 … high flight and crash landing

Though beset by a multitude of crises – the cost of living, housing, health and education services – the Albanese Labor government was returned comfortably in May, helped by a divided, incoherent, and seemingly out of touch opposition. For the rest the year, federal politics felt strangely frictionless with policy drift passing for stability. The Coalition remained locked in internal conflict, unable to present a credible alternative. The Greens, chastened by electoral defeat and in many formerly friendly quarters, ideological disillusionment, treaded water.

But beneath the surface, social cohesion frayed. Immigration debates sharpened. Antisemitism rose noticeably, no longer something Australians could pretend belonged elsewhere. Attacks on Jewish Australians forced a reckoning many had avoided and hoped would resolve once the tremors of the war in Gaza had ameliorated. Until 6.47pm on 7th December, a beautiful evening on Sydney’s iconic Bondi Beach. Sudden, brutal and in our summer playground, sectarian violence shattered the sense of distance Australians often feel from global disorder. At that moment, politics stopped feeling abstract. The world, with all its instability, barged in and brought the country down to earth.

See This Is What It Looks Like

Featured photograph and above:

A handful of bodies on Bondi Beach, and behind them, the howling infinite of expectation, obligation, and the careful rationing of human empathy. The smallness of the beach against the vastness of consequences. On December 20, 2025, Bondi’s iconic lifesavers formed a line stretching the entire length of the beach -silent, solemn, a nation visibly in mourning. Similar tributes unfolded from Perth to Byron Bay, gestures of unity in the face of a shock that touched the whole country.

The Year of the Chatbot: Promise, Power, and Risk

And now, a break from the doom and gloom …

2025 was the year when artificial intelligence became part of daily life. Chatbots ceased to be experimental and became integral, transforming from novelty to utility seemingly overnight. People used it to write, research, translate, plan, argue, comfort, and persuade; institutions and individuals adopted it instinctively. Setting tone as much as content, the ‘bots have lowered barriers to knowledge, sharpened thinking, and helped people articulate ideas they might otherwise struggle to express. Used well, they amplified curiosity rather than replace it.

The opportunities are obvious – but so are the risks. Systems that can clarify complexity can also flatten it. Chatbots sound confident even when wrong, smooth over disagreement, and made language cleaner, calmer, and more persuasive – but not necessarily truer. They reinforce confirmation bias, outrage, and tribal certainty, generating arguments instantly and flooding the zone with plausible-sounding text. As information has became faster, cheaper, and less reliable, Certainty has spread more easily than truth, so truth has to work much harder.

Dependence is subtler but real. Outsourcing thinking – summaries instead of reading, answers instead of wrestling – did not make humans stupid, but less patient. Nuance, doubt, and slow understanding became harder to justify in a world optimised for speed. Yet conversely, man people still seek context, history, and complexity. Used deliberately, AI could slow the pace, map contradictions, and hold multiple truths at once.

By the end of 2025, the question was no longer whether AI would shape public life – it already had. The real question is whether humans would use it as a shortcut, or as a discipline. The technology is neutral. The danger – and the promise – lies in how much thinking we are willing to give up, and how much responsibility we are prepared to keep.

See The promise and the peril of ChatGPT

Algorithm and blues

Alongside the chatbot sat a quieter, more insidious force: the algorithm itself. By 2025 it no longer simply organised information – it governed attention. What people saw, felt, and argued about was shaped less by importance than by engagement. To borrow from 20th century philosopher and communication theorist and educator Marshall McLuhan, the meme had become the message. Complex realities were compressed into images, slogans, clips, and talking points designed not to inform but to travel. The algorithm rewarded speed over reflection, certainty over doubt, heat over light. Politics, war, and grief were all flattened into content, stripped of context, and ranked by performance. What mattered most was not what was true or necessary, but what disseminated.

Passion without Wisdom

I wrote during the year that we seemed “full of passionate intensity” – Yeats’ phrase still apt in the twenty first century- but increasingly short on wisdom and insight. 2025 confirmed it. Anger was everywhere, empathy highly selective, certainty worn like armour. People felt deeply but thought narrowly. Moral energy surged but rarely slowed into understanding. The problem was not indifference; it was excess – too much feeling, too little reflection. In that environment, nuance looked like weakness and patience like complicity. What was missing was not information, but judgement – the harder work of holding contradiction, of resisting instant conclusions, of allowing complexity to temper conviction. Passion was abundant. Insight, increasingly rare.

Looking Toward 2026

Looking back on 2025, it seems that there were no endings, neither happy or sad. Just a promise, it seems, of more of the same. The year didn’t solve anything. It clarified things. And if it clarified anything, it was that the world has grown adept at managing, ignoring, or absorbing what it cannot fix. It revealed a world adjusting to permanent instability. In this year of echoes, refrains, and unfinished sentences.

Passion, intensity, and outrage were abundant, but patience, wisdom, and insight remained scarce. Democracies strained under internal and external pressures. Wars lingered unresolved. Technology reshaped thought and attention.

Some argue that hope springs eternal, that yet, even amid the drift and the fractures, glimpses of understanding and resistance persisted, that although the world has settled into its chaos, we can be riders on the storm. But, I fear, 2026 arrives not as break, a failsafe, a safety valve, but as continuation. It looms as a test of endurance rather than transformation. In my somnolent frame of mind, I’ve reached again for my Yeats. “Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold; mere anarchy is loosed upon the world, the blood-dimmed tide is loosed …”

After the chaos of 2024 and the hardening of 2025, the question is no longer what might go wrong. It’s what we’re prepared to live with.

And so we come to what In That Howling Infinite wrote in 2025.

What we wrote in 2025

It was a year that refused neat endings.

It began in a wasteland – Gaza as moral ground zero – and moved, restlessly, through revolutions real and imagined: Trump as symptom and accelerant, Putin as a man racing his own shadow, Syria forever at the crossroads where history idles and then accelerates without warning. Gaza returned, again and again, sunrise and false dawn, as spectacle and strategy; Sudan burned in near silence; Venezuela re-entered the frame as empire’s backyard as the US disinterred its Monrovian legacy. In That Howling Infinite featured pieces on each of these – several in many cases , twenty in all, plus a few of relevance to them, including an overview of journalist Robert Fisk’s last book (The Night of Power – Robert Fisk’s bitter epilogue). A broadranging historical piece written in the previous year and deferred, Modern history is built upon exodus and displacement, provided a corrective of sorts to the distorted narratives that have emerged in recent years due to a dearth of historical knowledge and the partisan weaponisation of words.

It was almost as light relief that we turned to other subjects. Of particular interest was AI. Approaching remorselessly yet almost unrecognised in recent years, it banged a loud gong and crept from curiosity to condition, from tool to weather system, quietly rewriting the newsroom, the internet, and the idea of authorship. ChatGPT and other chatbots appeared not as saviours but as promise and peril in equal measure. By year end, we were fretting about using ChatGPT too much and regarding it as something to moderate like alcohol or fatty foods. We published three pieces on the subject in what seemed like rapid succession, and then pestered out – sucked into the machinery, I fear.

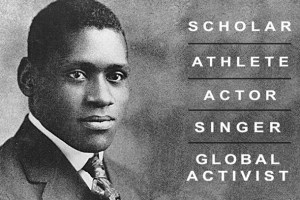

What with so much else attracting our attention, we nevertheless managed to find time for some history – including a particularly enthralling and indeed iconoclastic book on the fall of the Ottoman Empire; the story of an Anzac brigade lost in Greece in 1942; “the Lucky Country” revisited after half a century; and a piece long in the pipeline on the iconic singer and activist Paul Robeson.

In August, as on a whim, for light relief, we summoned up a nostalgic old Seekers’ song from the mid-sixties, a time when the world was on fire with war and rage much as it is today, but for us young folk back in the day, a time of hope and hedonism. For us, the carnival, clearly, is not over. The machinery is still whirring, the music still loud, and the lights still on. History is insisting on one more turn of the wheel, and the dawn, so often promised, so frequently invoked, has not yet broken.

January

The Gaza War … there are no winners in a wasteland

The way we were … reevaluating the Lucky Country

February

Let’s turn Gaza into Mar e Largo

Trump’s Second Coming … the new American Revolution

Cold Wind in Damascus … Syria at the crossroads

March

Trumps Revolution… he can destroy but he cannot create

Where have all the big books gone?

Putin’s War … an ageing autocrat seeks his place in history

April

The Trump Revolution … I run the country and the world

The Fall of the Ottoman Empire and the birth of Türkiye

Let Stalk Strine .. a lexicon of Australian as it was spoken (maybe)

May

The phantom of liberty … the paradoxes of conservativism

Shadows in search of a name … requiem for a war

The continuing battle for Australia’s history

July

A mighty voice … the odyssey of Paul Robeson

August

109 years of Mein Kampf … the book that ravaged a continent

High above the dawn is breaking … the unlikely origin of a poo song

September

Gaza sunrise or false dawn? Trump’s peace plan

Gaza sunrise or false dawn? Spectacle or Strategy

Will there ever be a Palestinian state?

Why Osana bin lost the battle but won the war

The Night of Power … Robert Fisks bitter epilogue

The promise and peril of ChatGPT

Who wrote this? The newsroom’s AI dilemma

October

AI and the future of the internet

Danger Angel … the ballad of Laura Loomer

November

A forgotten Anzac story in Greece’s bloody history

The most nihilistic war ever … Sudan’s waking nightmare

Answering the call … National Service in Britain 1945-1963

Tales of Yankee Power … at play in Americas backyard

December

Delo Kirova – the Kirov Case … a Soviet murder mystery

Between heaven and hell … Syria at the crossroads

This Is What It Looks Like

Tales of Yankee power … Why Venezuela, and why now?

Marco Rubio’s Venezuelan bargain

Read out reviews of prior years:

A song for 2026: Lost love at world’s end …

It is our custom to conclude our annual wrap with a particular song that caught our attention during the year. Last year, we chose Tears for Fears’ Mad World. It would be quite appropriate for 2025. But no repeats! so here is something very different. An outwardly melancholy song that is, in the most ineffable way quite uplifting. that’s what we reckon, anyway …

The Ticket Taker is on the surface a love song for the apocalypse; and it’s it’s one of the prettiest, most lyrically interesting songs I’ve heard in a long while. I could almost hear late-period Leonard Cohen and his choir of angels.

The apocalypse is both backdrop and metaphor. We’re not sure which. Is it really about a world ending, or just about the private ruin of a man left behind by love and fortune. The lyrics are opaque enough to evade final meaning, but resonant enough to keep circling back, like the ferry itself, between hope and futility. A love song, yes, but also a confession of entrapment: the gambler’s hope, the ark one cannot board.

The “Ticket Taker” song was written by Ben Miller and Jeff Prystowsky and is featured on The Low Anthem’s album Oh My God, Charlie Darwin. It features on Robert Plant’s latest foray into roots music – this time with English band Saving Grace. This flawless duet with Suzi Dian is mesmerising and magical.

Jeff will tell you that the song is “pure fiction,” that Ben “just made it up one day” – but fiction, as we know, has a way of smuggling deeper truths than fact dares admit.

Tonight’s the night when the waters rise

You’re groping in the dark

The ticket takers count the men who can afford the ark

The ticket takers will not board, for the ticket takers are tied

For five and change an hour, they will count the passers-by

They say the sky’s the limit, but the sky’s about to fall

Down come all them record books, cradle and all

They say before he bit it that the boxer felt no pain

But somewhere there’s a gambling man with a ticket in the rain

Mary Anne, I know I’m a long shot

But Mary Anne, what else have you got?

I am a ticket taker, many tickets have I torn

And I will be your ark, we will float above the storm

Many years have passed in this river town, I’ve sailed through many traps

I keep a stock of weapons should society collapse

I keep a stock of ammo, one of oil, and one of gold

I keep a place for Mary Anne, soon she will come home

Mary Anne, I know I’m a long shot

But Mary Anne, what else have you got?

I am a ticket taker, many tickets have I torn

And I will be your ark, we will float above the storm

Mary Anne, I know I’m a long shot

But Mary Anne, what else have you got?

I am a ticket taker, many tickets have I torn

And I will be your ark