“Old stuff. The Old World is full of it. But objects speak.They tell us things”.

The word “loot” derives from from the Hindi lūṭ or “booty” either from Sanskrit loptra, “booty, stolen property” orluṇṭ, “to rob, plunder”. It is one of the many words that entered into the anglophone vernacular in the wake of European imperial expansion. Charles James’s “Military Dictionary, London 1802, defines it as “Indian term for plunder or pillage”, and “goods taken from an enemy”. Like the very concept of empire itself, the word is a loaded one, loaded with historical memories, with national identities, and with differential moralities. Are goods taken in war by the victors as reparations or recompense for blood and treasure spent? Are they stolen goods that the perpetrators have a moral obligation to return to their rightful owners – or, as is the case with most of the inheritors of once imperial patrimony, the current territorial powers that be.

These questions loom large in the commentatary of an entertaining if lightweight, and yet, most informative programme running on the ABC at the moment, called, provocatively, Stuff the British Stole.

In this Australian-Canadian production Marc Fennell, the affable host the ABC’s Mastermind, trots the globe recounting the stories of the artefacts that ended up in British and Australian museums, galleries and churches during the days of Empire. Arriving in the wake of global protests that have seen statues ripped down and colonial legacies scrutinised with renewed vigour, the series offers an accessible beginner’s guide to the British empire’s long shadow and sticky fingers. Along the way, he encounters academics and diasporic communities for whom these objects, and the dispossession, death and cultural erasure they represent, have been open wounds for generations.

Each artefact acquired during the age of Empire is a reminder of colonial rule, be this benign or oppressive as determined from the perspective of the observer. For a long time, Britain’s best excuse for having nicked and then held on to many of these priceless antiquities has been that in a world of chaos and destruction, its institutions have long been the safest place to keep its ill-gotten treasures. The programme asks rhetorically in commentary and actually to museum curators: “is there an honourable way of handing in to your stolen stash?” Shouldn’t you be handing it back to its people? “Is this loot” asks the narrator of the director of the Art Galley of NSW. It is a public art gallery”, he replies.” … it belongs to the people of NSW … it’s there for education and discussion … I think it’s best not to use words like this right away … it was coming out of the rubble in the middle of a war zone … its a bit problematic”.

Britain was not the sole perpetrator of plunder, mind. A lot of loot of found its way into the museums of other European empires and and also the United States and Russia. And it was acquired in much the same way, in a mix of altruism, academic inquiry, subterfuge and outright banditry.

In our own travels, Adèle and I encountered an amusing tale of imperial skulduggery. When we were in Damascus, we stood by the modest catafalque of the celebrated Muslim war lord Salah ad Din al Ayubi, known in the west as Saladin, as our guide recounted the story of how before the First World War, the German Kaiser visited the Levant, then under the rule of the Ottoman Empire. Whilst visiting the Old City of Damascus, Wilhelm cast covetous eyes over the famous sultan’s casket. It is said that his entourage attempted to poach Salah ad Din’s tomb and spirit it back to Germany, but was intercepted by the Sultan’s police. By way of contrition, the emperor presented Damascus with a gaudy new catafalque more suited, he reckoned, to the last resting place of a renowned warrior. The two monuments now sit side by side in Salah ad Din’s small mausoleum beside the looming Roman wall of the splendid Umayyad Mosque, and pilgrims weep beside them. Our guide, a Syrian Kurd, upbraided elderly fellahin visiting from the countryside for praying at the empty fake – “don’t you know that Salah ad Din al Ayubi was not Arab but Kurdi, and he is in that tomb, not this one!”

But I digress …

A stone and a rock, a statue and a shirt …

Episode One kicks off a tad earlier than Imperial age, and closer to home with Scotland’s Stone of Scone, the big brick upon which Scottish kings were crowned until Edward I took it home to Westminster as a symbol of Sassenach conquest. It has seated the arses of British monarchs ever since, and though it was sent back home to Edinburgh in recent times as a recognition of Scottish nationalist sympathies, it will doubtless be lent to London for the enthronement of Charles, Third of His Name.

But the usual imperial suspects follow. There’s the Koh i Nor Diamond “gifted” to Queen Victoria from an adolescent Duleep Singh, maharajah of the independent but defeated state of Punjab, along with his empire, in the mid-19th century It is now in Britain’s Crown Jewels, tucked away in the vaults of Tower of London (the ones on show to the public are replicas). Once the centrepiece of the Great Exhibition, the diamond is now set in a crown that Queen Consort Camilla may or may not wear at her husband’s coronation in May. Britain’s royals have amassed a Smaug-like treasure trove of bling that might featured in future lists of Stuff the British Stole.

The Peking Shadow Boxer is an ancient bronze statue “rescued” from the ruins of war by a British sea captain during the Boxer Rebellion at end of the nineteenth century and now somewhere in the storerooms of the Art Gallery of New South Wales – the rebellion was one of Australia’s first overseas war. Then there is the story of a ceremonial war-shirt once worn by Native American Blackfoot chief Crow Foot, his “uniform’ or regalia, if you will, “gifted” (no one really knows how or why) to the Mounties during treaty negotiations when Canada was a British Dominion, and now, “in a place where it does not belong”, in London’s V&A Museum. This episode was particularly visceral. Coming almost contemporaneously with the recent revelations of what happened in Canadian “residential schools” that endeavoured to “take the Indian out if the Indians”.

We’ve heard that one in Australia too as we still struggle to come to terms with our past. As Mark Twain quipped, history might not repeat, but sometimes it rhymes. And it is passing ironic that the final episode is a brief, sadly predictable chapter in Australia’s frontier war in the early Nineteenth Century.

The hunt for Yagan’s head

Yagan was warrior and Noongar man whose people lived by what is now the Swan River near Perth in Western Australia. Settlement land grabs and tit for tat robberies and murders, and revenge for the deaths for his brother and father provoked him to violence. The colonial authorities put a price of his head, dead or alive, for a payback killing in 1834-35 and he was shot in the back by two young settlers. His head cut off and was paraded around the colony to send a message to his people.

It took over a century to track down Yagan’s head. Ken Colberg, a Noongar war veteran and elder, made it his mission to find it. He traced it to a house in London – a colonial lieutenant had brought it back to England and endeavoured to sell it to a surgeon who was interested in such “trophies “. The surgeon declined to purchase it so the soldier conveyed it to Liverpool where he flogged it to Liverpool Museum. Over a century later, on the instructions of the museum, it was buried in Everton Cemetery near Liverpool in an unmarked common grave along other with other remains including 22 still born babies interred by a local hospital. Two English archaeologists agreed to assist Ken in his quest, tracing the location of the grave and negotiating with the authorities and descendants of the deceased children to effect Yagan’s exhumation.

It was handed over to a Noongar delegation in Liverpool Town Hall on 28th August 1997 – the day Princess Diana died in Paris. Ken made a passing reference to this during the ceremony: “That is how nature goes … Nature is a carrier of all good things and all bad things. And because the Poms did the wrong thing, they now have to suffer”. That went down well in the. Australian media, his comment prompted a media with newspapers receiving many letters from the public expressing shock and anger. Ken later claimed that his comments had been misinterpreted.

Yagan’s remains were finally laid to rest in Australian soil, on the banks of the Swan River on Noongar country.

And so concluded the first season of Stuff the British Stole. But there’s more to come – season two is promised and is already available as a podcast. It includes Tipu Sultan’s mechanical Tiger from Bengal, India, presently in the British Museum, commissioned by the sultan and depicting a tiger munching down on a prostrate English soldier. That one was taken when Tipu met his doom at the hands of Clive (of India, that is, and looter in chief of Indian artefacts). There’s there’s a revered chalice from Cork from a time when catholic worship was banned by British authorities; the Gweagal Shield acquired by Captain Cook when he hove to in Botany Bay; and the Makomokai tattooed heads from Aotearoa. And, of course, the most celebrated of artefact of all, the Elgin Marbles that most folk associate with the British Museum rather than with the Athens Parthenon which has served successively as a temple, church and mosque before Venetian ships bombed it in the seventeenth century – and from whence the eponymous Lord Elgin lifted them on the dubious pretext of preservation and plonked them down in perfidious Albion.

Which brings us to the mosaic …

This is the story that enticed me into Stuff the British Stole and thence, into this post. Having enjoyed half a century of interest in the Middle East, I was immediately sucked in. And as with Yagan’s los head, it too has as Australian connection.

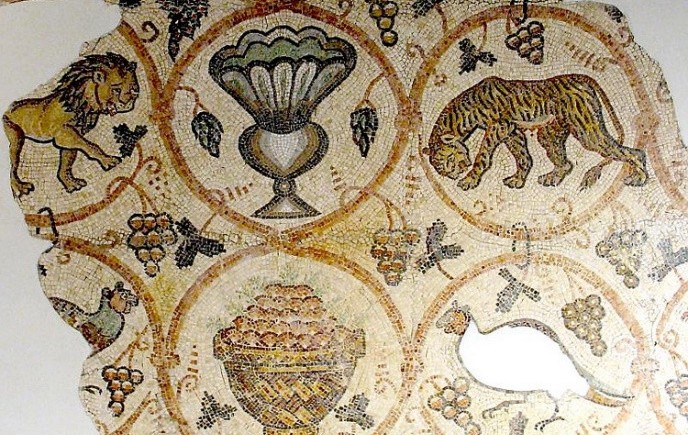

It is April 1917, during the second battle of Gaza, and British General Allenby’s army of soldiers from Britain and its empire is pushing northwards across the Negev Desert towards Ottoman-ruled Gaza and thence Jerusalem. It’s not officially called Palestine yet – the old Roman name, favoured by theologians, romantics, and British tourists and politicians, would not enter world politics and controversy for a few years yet. The Reverend William Maitland Woods is chaplain of the Australian and New Zealand Anzac division, and soldiers of a Queensland brigade of the Australian Light Horse are digging trenches at Besor Springs, near Gaza. The Reverend is an amateur archeologist and made a habit of entertaining the troops with stories about the Holy Lands where they were campaigning. The soldiers uncover the remnant of a 6th Century Byzantine mosaic dating from 561-562, during the reign of Emperor Justinian. A excited chaplain seeks professional advice from curators at the Cairo Museum and is given permission to organise a group of volunteers to uncover and remove the remains. Sapper McFarlane of the New Zealand Wireless Troop was given the job of drawing what they uncovered. That’s him in the picture below.

The reverend convinces his higher-ups that the mosaic must be saved, and sixty three crates are sent to Cairo. Egypt at the time was a British “dependency “ (good word, that).

There then commenced a tussle between British high command in Cairo and the Australian defence department. By September 1917, the Australian Records Section was feverishly collecting battlefield trophies. Charles Bean the official ANZAC historian liked to call them “relics”, consistent with the reverential language of “spirit”, “sacrifice” and “the fallen” he afforded his soldiers. The British : “It’s not a trophy of war – you cannot have it – it may be returned” or words to that effect. TheAussies: we wanted stuff for our prospective Australian War Museum, and anyhow, we’ve shed blood in this fight”.

And so, what would be called the Shellal Mosaic ended up in Canberra. Most of it, anyway. Other fragments found their way to St James Church in the Sydney CBD and in a church in Brisbane. It is believed that some diggers took pieces too. In 1941, when the War Memorial was under construction, an appeal was sent out to ageing members of the light horse regiments to return the bits they’d souvenired, but there were few, if any, volunteers.

Concerned, with very good reason, that the treasure might not get all the way Down Under, Woods gathered up several baskets of tesserae from the site, the individual fragments from which a mosaic is made, and commissioned an artisan to fashion an exact replica of the inscription headstone, one metre by half a metrre. He gave this to a friend, a Colonel John Arnott who at war’s end, returned to his family property at Coolah in rural New South Wakes and embedded itinto his garden steps. The farmhouse and its steps are with the family today.

Ancient History interlude: What makes the Shellal Mosaic such a significant archaeological find? For one, it was a Christian chapel from the Byzantine period when Hellenic pagan culture was giving way to Christianity. For two, the mosaic was made of marble, an expensive material and not commonly used other than by the very wealthy. And for three, the use of exotic animals from different lands, such as lions, tigers, flamingos and peacocks, common images in Byzantine art, all paying homage to a central chalice, could point to other pagan races and lands embracing Christianity.

Yet, the tale gets curiouser and curiouser …

During the excavations, Maitland Woods discovered a chamber beneath the mosaic. It contained human bones lying with its feet to the east and its arms closed on the chest. The bones and inscriptions on the mosaic got the reverend quite excited, more so than the more mosaic itself as a rough translation of the inscription suggested to him that let him they were the bones were those of St George – of England and dragon fame, not the Dragons.the league football team of the eponymous suburb in southern Sydney which was not established until 1920. They were not, however. Saintly George lived in intolerant pagan Roman times and was martyred for his faith. More likely, they belonged to a local bishop time called as George. Woods feared these would be sent to England in perpetuity so he packed them up and gave a ‘parcel’ to his friend, Reverend Herbert Rose, for safe keeping, and this found its way to Rose’s home parish of St Anne’s in Strathfield in Sydney’s inner west, where they are interred in the floor in front of the church’s communion table. Woods’ fears were justified. During the delivery of the remaining bones from Cairo to London, George’s skull disappeared, never to be seen again.

As Yagan would aver, heads do that.

© Paul Hemphill 2023 All rights reserved

For further history stories in In That Howling Infinite, see Foggy Ruins of time – from history’s back pages

For stories about the Middle East, see A Middle East Miscellany

For stories about Australia and also the Frontier Wars, see Down Under – Australian history and politics

Bronze, stone and possum fur