Under African Skies

A decade or so ago, British born South African singer and songwriter the late and much lamented Johnny Clegg (he died of cancer in July 2018) performed with his band at Newtown’s antique Enmore Theatre in inner Sydney. Renowned worldwide for his fusion of western and South African township music, the “White Zulu” as he was called, had captivated us and thousands of others with his bilingual songs and anthemic choruses – and he danced! The high kicking Zulu warrior dances of rejoicing, of rites of passage, and of war. And his choruses! Could he write choruses. They didn’t rise – they soared like African eagles and they made the hairs on the back of our heads stand up. The audience would sing along entranced, enthralled and seemingly word-perfect in a language they could not even begin understand. Towards the climax of his concert, when such was the energy you could sense an ascension to heights of glory, he’d introduce Impi, his story of the battle of Isandhlwana on January 22nd 1879, a battle considered the greatest ever defeat of a modern army by an indigenous people. A thousand voices joined him in song …

Impi! wo ‘nans’ impi iyeza

Obani bengathinta amabhubesi?

War, O here comes war!

Who can touch the lions?

It was an ironic moment in time and historical memory.

The South Africa’s apartheid regime has long since fallen, and Johnny Clegg was world famous for his decades-long anti-apartheid stand and for his fusion of western and African music and lyrics. Paul Simon had cited Clegg’s early band Juluka as an influence in his own iconic album Graceland. Whenever Clegg played in Australia, white South Africans made up a large proportion of the audience. And they and us, again mostly white, would sing along and even dance in the aisles. But very few there that night would have much of an awareness of the historical and cultural backdrop to his songs – particularly the events described in Impi, those leading up to it, and the aftermath.

Indeed, few westerners are aware let alone knowledgeable of southern Africa’s history. It is a faraway land, distant geographically and culturally from the northern hemisphere, and we known more for its wildlife and its troubles. For a long, long time it was called “the dark Continent”. In the excellent British espionage thriller Spooks, the Foreign Secretary declares contemptuously: “The continent of Africa in nothing but an an economic albatross around our necks. It’s a continent of genocidal maniacs living in the Dark Ages”.

Moreover, few people actually interested in the British Empire and the imperial wars of conquest of what is now the Republic of South Africa are aware of the fact that the military disaster at Isandhlwana and the heroic defense of Rorke’s Drift in the southern summer of January 1879 were the chaotic prelude to the conquest of the powerful and independent kwaZulu, a kingdom established half century earlier by the charismatic and canny but brutal, paranoid and arguably psychotic warlord Shaka Zulu.

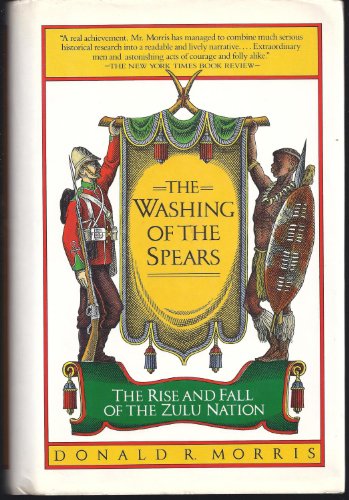

I do not profess be an expert although cognizant of African History and politics from my own reading over the years, ranging from studying sub-Saharan politics in the late sixties to reading James A Mitchener’s sprawling novel The Covenant (1980), which traces the history, interaction, and conflicts between South Africa’s diverse populations, from prehistoric times up to the 1970s. Recently, I read Australian author Peter Fitzsimmon’s The Breaker in which he relates the story of Boer War, and Donald R Morris’s critically acclaimed The Washing of the Spears – the Rise and Fall of the Great Zulu Nation (1966).

The Washing of the Spears

American historian Donald R Morris’s seminal work on the rise and fall of the Zulu nation is near on sixty years old, and it shows in both the archaic lyricism of his prose – a style characteristic of his academic peers – and that mid twentieth century conservative mindset of shifting presumptions and prejudices that was so much part of the sixties, that inform his point of view of events so long ago that shaped the development of modern Africa.

The book takes its title from the Zulu idiom for shedding the blood of enemies with the short tabbing spear developed by Shaka himself from the traditional Bantu assegai – an onomatopoeic word for the sound made when the spear was extracted from a wound.

While hardly the book to consult for a fast grasp of the outlines of Zulu history, it provides a sweeping, all-inclusive military, political, and personal record. It is a rousing narrative and highly informative, although it does get bogged down in the minutiae of political, administrative and military matters. The book is a close-typed 612 pager. The first 214 describe the rise of Zulu power – Shaka, Dingaan, Mpandi and Cetshwayo.

The battles are done and dusted in just seventy six pages. The remainder is taken up with the preparations for the invasion of Zululand, the second invasion, the defeat of the Zulus at Ulundi and the annexation of Zululand to the colony of Natal.

But this does not detract for one moment from the quality and detail, and also, the empathy and objectivity of Morris’s narrative. He treats the Zulu, as well as the Boers and British, fairly, portraying both admirable behaviors and the foibles of all parties. Whilst some readers might conclude that despite its evenhanded approach, it fails to meet the high standards of contemporary political correctness, I am highly impressed by the author’s undisguised empathy for the Zulu people as demonstrated by the depth of his research into Zulu customs and etymology and the degree to which he describes by name and in detail the Zulu regiments arrayed against the Crown.

When it comes to the timeline of the battles of Isandhlwana and Rorke’s Drift, which occurred almost in tandem, it is a riveting re-enactment of the combat – a timeline that spoke to the the big screen films, Zulu released in 1964 and Zulu Dawn which depicted Isandhlwana and was released to coincide with its centenary in 1979.

Here they come, black as hell and as thick as grass!

Long story short, the Zulu War of 1879 was an unprovoked, preventive war waged by an expansionist imperial power against an independent kingdom. After the initial disaster at Isandlwana, the native state was broken in a conquest that largely determined the place of the indigenous population within the European civilization of southern Africa, and it freed that civilization from any imperative nor the willingness listen to the voice of black Africa for nigh on one hundred years.

The Zulus did not want war, and were in effect enticed into it by colonial authorities who desired to break Zulu power once and for all. Morris describes in great detail the depths of skulduggery Britain’s representatives on the ground were pro armed to descend to. Pertains were in plain view, both the gathering of military and paramilitary forces and the supply chain and logistic required to sustain them in the field.

Once committed, the outcome was inevitable. The first invasion ended, however, in disaster – the massacre at Isandhlwana. But this was more due to the mistakes made by British commanders than to the undeniable overwhelming numbers and resolve of the Impi deployed against them. Lieutenant-General Lord Chelmsford divided his numerically inferior forces. The relatively small force left behind at the base camp at Isandlwana as poorly deployed, denying them the advantage of concentrated fire. critical ammunition boxes that could not be opened quickly because the tools were inadequate, and scouting that was lackadaisical in the extreme – so much so that 20000 warriors were able to gather in a ravine close to the camp undetected until it was too late.

The rest, as they say, is the study of military history. The defense of the border mission at Rorke’s Drift at about the same time as the battle was reacting its climax, itself a sideshow as thousands of warriors stormed the beleaguered outpost. The quotation at the head of this section is the cry of Chaplain George Smith on lookout on the ridge behind the mission. Rorke’s Drift was an opportunistic target for a small army of Zulus who had not engaged in the main battle, and probably had no intention of proceeding onward into Natal – Cetshwayo had expressly forbidden it. In the wake of the disaster, it became the stuff of legend, More Victoria Crosses were awarded here than in any other engagement by the British Army.

The next time, General Chelmsford took no chances. Thousands of soldiers and horsemen supported by thousands of wagons and tens is tens of thousands of draught animals slowly traversed miles and mile of uncharted bush to array before Cetshwayo’s Royal kraal at Ulundi. Maximum force was applied on a chosen field of battle and massed firepower of combined arms – Henry Martini rifles, cannon and Gatling guns against waves of Zulus attend with assegais and cow hide shields with cavalry of the flanks to harry the foe once he was broken and scattered.

Morris’s conclusion to the battle of Ulundi is a poignant synopsis of the rise and fall of the Zulu nation. It is well worth reproducing in part:

“The camp on the the White Umfolozi was quiet that night. The war was over, and the battalions would soon be sailing to England. Chelmsford slept the sleep of the just. He had successfully concluded two arduous campaigns in a year and a half. Providence has been very good to him and he could hold his head high in the future. Sir Garnet Wolsey was welcome to whatever remained of the Zulu campaign.

The flames across the river died away, and the drifting black smoke was hidden by the soft night. A few miles to the west of the sleeping camp stood th kwaNabomba kraal, where Shaka had arrives 63 years ago to claim his inheritance. He had found an apathetic clan no one ever heard of, who numbered less than the Zulu dead that now lay and buried across the river, and out of them he had fashioned an army, and that army, he had built an empire.The proud and fearless regiments had carried that assegais south to the Great Kei, west to the high wall of the Drakensberg Range, and north to Delagoa Bay. He had smashed more than 1000 clans and driven them from their ancestral lands, and more than 2 million people had perished in the aftermath of the rise of his empire, which had survived in by a scant 50 years. The last independent king of the Zulus was now a homeless refugee without a home, and his capital lay ashes. His army had ceased to exist, and what was left of the regiments had silently dispersed to seek their own kraals. The house of Shaka had fallen, and the Zulu empire was no more …

… The cost has been high. The house of Shaka had been overthrown and Zulu kingdom fragmented. Some 8000 Zulu worries it died and more than twice a number had been wounded, to perish or recover without medical attention. Thousand of Zulu cattle had been runoff into Natal or slaughtered to feed the invaders, scores of kraals had been burned and the fields in fields had gone untended …

… Over 32,400 men and taking the field in the Zulu campaign. The official British returns listed 76 officers and 1007 men killed in action and 37 officers and 206 men wounded. Close to 1000 Natal kaffirs had been killed; the returns were never completed. An additional 17 officers and 330 men had died of disease and 99 officers and 1286 men had to be invalids home. In all, 1430 Europeans had died, over 1300 of them at Isandhlwana. The war cost the crown £5,230,323 – beyond the normal expense of the military establishment: the naval transport alone cost £700,000. A tremendous sum gone for the land transport which has employed over 4000 European and native drivers and leaders, more than 2500 carts and wagons, and has seen as many as 32,000 draft animals on the establishment at one time. No one ever counted the tens of thousands of oxen that had died.”

The captains and the kings depart

The world at large took little note of the war – except perhaps for France. In a brief chapter entitled The Prince Imperial, Morris recounts the story of how the son of the deposed and exiled Emperor Napoleon III of France, a graduate of Woolwich military academy had joined the invasion force and had perished when his scouting patrol was was ambushed. As Morris describes it, the displays of mourning by the British establishment and also the public far exceeded their reaction to the deaths at Isandlwana.

But the breaking of Zulu power, removing the threat it posed to the emerging Boer republics, and Britain’s halting progress towards the confederation of the South Africa colonies, was to have a critical influence what came afterwards: two Anglo-Boer Wars, the creation of the Union, and the emergence of the white supremacist Apartheid republic with its system of racial segregation which came to an end in the early nineteen nineties in a series of steps that led to the formation of a democratic government in 1994.

As for Cetshwayo, he was tracked down and captured after Ulundi. In an early form of home detention, he was detained in Capetown. In time, he became in the eyes of the British public, a tragic, less the bloodthirsty Bantu as he’d been portrayed during the war, and more the noble savage as victim of predatory imperialism. He journeyed to England and was well received by all, and even enjoyed an audience with Queen Victoria who treated him with respect and amity. On his return to Capetown, moves to restore him to his throne were truncated by his death – ostensibly poisoned by rivals. Shaka’s heirs are recognized as kings in kwaZulu to this day.

In a memorial wall at Ulundi, the battle that ended the way and the Zulu nation, there is a small plaque that reads: “In memory of the brave warriors who fell herein 1979 in defense of the old Zulu culture”. From what I can gather, it the only memorial erected to honour the Zulu nation.

A cinematic coda

Reading Morris’s book recently, I succumbed to the urge to watch both Zulu and its later prequel Zulu Dawn.. Their cinematic technology, character development and acting have not stood the test of time – and few of the lead characters are still with us – one cannot fault their faithfulness to the author’s narrative.

What the films miss, however, is what I perceived as Morris’s oblique perspective of the Zulu war. They present the conflict in literal black and white – the mission civilatrice, white man’s burden, whatever, bringing justice and order, not in that order, to bloodthirsty savages. In Zulu, the doughty British soldiers are well led and respond with courage and resilience. In Zulu Dawn, those soldiers are badly led by their snobbish and ineffectual leaders, and most particularly by General Chelmsford portrayed with smarmy insouciance by Peter O’Toole, and his supercilious staff. The “good guys”, Denholm Elliot’s Colonel Pulaine, Burt Lancaster’s Colonel Dunford, and Simon Ward’s Lieutenant Vereker and others are cardboard cutouts. Lieutenants Chard and Bromhead,the commanders at Rorke’s Drift, played by Stanley Baker and Michael Caine respectively, are the acme of bulldog spirit and stiff upper lip, and poster boys for many an imperial Facebook page.

The rest of a large cast of extras, be they the Boer and native auxiliaries or the massed Zulu regiments chanting “uSuthu! USuthu!”, the war cry of the Shaka dynasty, are the backdrop to imperial derring do and disaster. In both movies, the scenes at the Zulu kraals present the cinematographers with an opportunity to indulge in a bit of National Geographic soft porn with dusky, lithe and bare-breasted maidens dancing in lines towards long-limbed and youthful Zulu warriors. Men march, men charge, men stand, men run, and men die. The action is not graphic by modern standards – no Vikings or Game of Thrones blood and gore here.

Mark Stoler’s Things have changed blog spot provides a brief but informative review of The Washing of the Spears, including a synopsis of the story line, including some interesting facts about the author. I have reproduced it below for your convenience- but the eclectic blog, similar in content and diversity to In That Howling Infinite, is worth checking out.

© Paul Hemphill 2022. All rights reserved

See also In In That Howling Infinite: The ballad of ‘the Breaker’ – Australia’s Boer War

Impi

John Clegg

Impi! wo ‘nans’ impi iyeza

Obani bengathinta amabhubesi?

Impi! wo ‘nans’ impi iyeza

Obani bengathinta amabhubesi?

Impi! wo ‘nans’ impi iyeza

Obani bengathinta amabhubesi?

Impi! wo ‘nans’ impi iyeza

Obani bengathinta amabhubesi?

All along the river

Chelmsford’s army lay asleep

Come to crush the Children of Mageba

Come to exact the Realm’s price for peace

And in the morning as they saddled up to ride

Their eyes shone with the fire and the steel

The General told them of the task that lay ahead

To bring the People of the Sky to heel

Impi! wo ‘nans’ impi iyeza

Obani bengathinta amabhubesi?

Impi! wo ‘nans’ impi iyeza

Obani bengathinta amabhubesi?

Mud and sweat on polished leather

Warm rain seeping to the bone

They rode through the season’s wet weather

Straining for a glimpse of the foe

Hopeless battalion destined to die

Broken by the Benders of Kings

Vainglorious General, Victorian pride

Would cost him and eight hundred men their lives

Impi! wo ‘nans’ impi iyeza

Obani bengathinta amabhubesi?

Impi! wo ‘nans’ impi iyeza

Obani bengathinta amabhubesi?

They came to the side of the mountain

Scouts rode out to spy the land

Even as the Realm’s soldiers lay resting

Mageba’s forces were soon at hand

And by the evening the vultures were wheeling

Above the ruins where the fallen lay

An ancient song as old as the ashes

Echoed as Mageba’s warriors marched away

Impi! wo ‘nans’ impi iyeza

Obani bengathinta amabhubesi?

Impi! wo ‘nans’ impi iyeza

Obani bengathinta amabhubesi?

Impi! wo ‘nans’ impi iyeza

Obani bengathinta amabhubesi?

Impi! wo ‘nans’ impi iyeza

Obani bengathinta amabhubesi?

Impi! wo ‘nans’ impi iyeza

Obani bengathinta amabhubesi?

Impi! wo ‘nans’ impi iyeza

Obani bengathinta amabhubesi?

Impi! wo ‘nans’ impi iyeza

Zulu: The Washing Of The Spears

Things Have Changed blogspot, Mark Stoler, 24th September 2016

I first came across the tale of Rorke’s Drift in a long-forgotten collection of stirring deeds written for children. I could not have been more than ten years old at the time . . .

The Defense of Rorke’s Drift, Alphonse de Neuville, 1880

The Defense of Rorke’s Drift, Alphonse de Neuville, 1880Donald Morris (1924-2002) began research for The Washing of the Spears in 1956, completing the bulk of it between 1958 and 1962 when, according to the 1965 introduction to his book, he was “a naval officer stationed in Berlin“. Fascinated by the Battle of Rorke’s Drift, which occurred on January 22-3, 1879, and the stunning defeat of the British Army by the Zulus at Isandhlwana, earlier that same day, he planned to write a magazine article on the battles, until persuaded by Ernest Hemingway to compose an account of the entire Zulu War of 1879, as none had ever been published in the United States.

Islandhlwana, 1879,

The mention of Hemingway, alerted me that Morris might be an interesting person in his own right. I originally read the book in the mid-1970s on the recommendation of an acquaintance who had been enthralled by it. At that time, there was very little information available on the author. More recently I’ve read the 1998 edition (the book has gone through several printings over the years), as well as Morris’ 2002 obituary and found that, indeed, he was quite an interesting character.

Educated at the Horace Mann School for Boys in New York City, he entered the navy in 1942 and then went on to the Naval Academy, graduating in 1948, remaining on active service until 1956, and retiring as a Lieutenant Commander. It turns out that his assignment as a naval officer in Berlin was a cover; from 1956 through 1972 he was a CIA officer in Soviet counterespionage, serving in Berlin, Paris, the Congo and Vietnam. From 1972 through 1989 he was foreign affairs columnist for the Houston Post. Morris spoke German, French, Afrikaans, Russian and Chinese, held a commercial pilot’s license and was a certified flight instructor.

Once Morris took up Hemingway’s suggestion and began research on the Zulu War, he realized he needed to find out more about its origins. It was a process that ended up taking him all the way back to the early 17th century, when both the Dutch and the Bantus (of whom the Zulu were a subgroup) first entered the lands that later became the Republic of South Africa, the Dutch in the southwest via the Capetown settlement and the cattle-herding Bantus migrating from the north. The result is a 603 page epic (excluding footnotes), encompassing almost 300 years of history, and all of it accomplished without visiting South Africa.

Morris tells us of the fate of the Bushmen and Hottentots, most of whom were destroyed, caught between the advancing Dutch settlers (who came to call themselves Boers) and Bantus. We learn of the coming of the English in the late 18th century, which accelerated the migration of Boer farmers, north, northeast and east of Capetown in order to escape British control. We learn of the emergence of the Zulu nation in the 1820s under Shaka, and of his brilliant in leadership, tactics and strategy as well as his erratic behavior and brutality. Zulu impi)

The innovative military system he developed and the incredible endurance and bravery of the Zulu warriors, made Shaka’s kingdom feared across the land, among both natives, Boer (who had also come to consider themselves natives) and English. Under Shaka and his successors, the Zulu controlled most of the coastal strip of southern Africa, eventually coming up against the Boers, who began their Great Trek in the 1830s to escape the encroaching English; a journey which took them to what was to become the Orange Free State, the Transvaal and Natal.

(Map by Lt

Map made by Lieutenant Chard, co-commander at Rorke’s Drift

Morris takes us through the conclusion of the war in which the British regrouped and reinvaded, finally conquering the Zulu, and of the sad decline of Zululand over the next decades.

The book is a rousing narrative and highly informative. My only criticism is that it does become bogged down at one point in the minutiae of the formation of the Natal Colony and the very confusing religious disputes among its European settlers. About 50 pages could have been edited out.

The author treats the Zulu, as well as the Boers and British, fairly, portraying both admirable behaviors and the foibles of all parties. Given the times it was written in, my guess is it would not meet with the full approval of today’s social justice crowd, despite its evenhanded approach.

I’ve read a bit about more recent historiography of the Zulu and this general period in South African history to get a sense of how the book is regarded today. In the decades since its publication much new information about the Zulu kingdom has become available that provides a more complete explanation of their thinking in the run up to the 1879 war and their strategy in conducting it. Some different takes on the campaign and battles have also become available. Nonetheless, the book remains highly regarded.

The 1988 edition of the book contains an unusual introduction from Mangosuthu Buthelezi, Chief Minister of kwaZulu, and descendant of King Shaka. In it, Buthelezi gives tribute to Morris’ efforts, placing it in the context of its time:

Forced to use the only sources available in the vast amount of research he undertook in order to write the book, he nevertheless could not entirely escape the clutches of a very biased recording of the past. It is, however, not the extent to which some of his observations could be questioned that is important, for at the time of its publication in 1966, The Washing of the Spears was the least biased of all accounts ever published about kwaZulu.

He traces the process of colonial domination over the Zulu people and step by step shows how the British occupation of Natal led to the formation of what the world now knows as an apartheid society. He writes with indignant awareness of how today’s apartheid society was made possible by brutal conquest and subjugation during British colonial times, and he had attributed historically important roles to the Zulu kings in his awareness of the Black man’s struggle against oppression.

He undertook a mammoth task and acquitted himself brilliantly. The Zulu people owe a debt of gratitude to Donald Morris. He saw the world through our eyes and he was at his brilliant best in writing about the major White actors who shaped events in South Africa during the nineteenth century. He stands with us as we revere the memory of people such as Bishop Colenso; he stands with us in the knowledge of what Sir Bartle Frere did; and he stands with us in an intense awareness of how people like Sir Theophilus Shepstone turned traitor to the people who had befriended him and about whom he talked as his friends.

Of course no account of the Zulu War, or at least no account at THC, would be complete without mention of the 1964 film Zulu, about the fight at Rorke’s Drift. Starring as the two young officers in charge of the defense were Stanley Baker as Lt. John Chard and newcomer Michael Caine as Lt Gonville Bromhead. King Cetshwayo was played by his great-grandson Chief Buthelezi! I quite enjoyed the movie as a teenager. Here’s a nice piece on the film from an historical perspective.