… they were standin’ on the shore one day

Saw the white sails in the sun

Wasn’t long before they felt the sting

White man, white law, white gun

Solid Rock, Goanna 1982

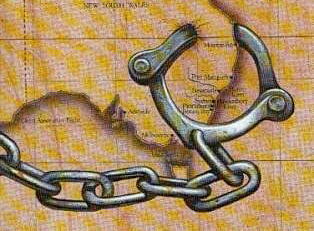

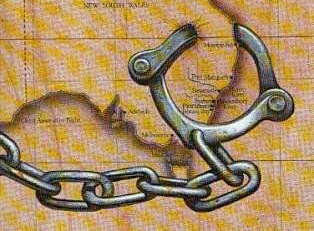

As indigenous author and academic Victoria Grieves-Williams writes below in her essay regarding journalist David Marr’s recently published family history: “We live in a time of reckoning over the colonisation of the land mass that we now know as Australia. While British officials carefully avoided acknowledging that people existed on this continent prior to their arrival by adopting the infamous doctrine of terra nullius, many Australians are now re-examining the historical basis of their presence here. They know that they enjoy the material wealth and lifestyle of the lands they have come to call home and until recently there was no need to doubt, or be self-conscious, about Australia being “home”. Yet there clearly were people here, and it was only the idea of an empty country that made it possible for agents of Empire, such as the Uhr brothers, ancestors of the journalist David Marr, to go about attempting to empty it”.

I’ve written often about the indigenous history of our country. The following passage from my piece on Australia’s The Frontier Wars. This passage therefrom encapsulates my perspective:

”There is a darkness at the heart of democracy in the new world “settler colonial” countries like Australia and New Zealand, America and Canada that we struggle to come to terms with. For almost all of our history, we’ve confronted the gulf between the ideal of political equality and the reality of indigenous dispossession and exclusion. To a greater or lesser extent, with greater or lesser success, we’ve laboured to close the gap. It’s a slow train coming, and in Australia in these divisive days, it doesn’t take much to reignite our “history wars” as we negotiate competing narratives and debate the “black armband” and “white blindfold” versions of our national story”.

Below are pieces published in In That Howling Infinite in regard to Australian history and politics as these relate to Indigenous Australians:

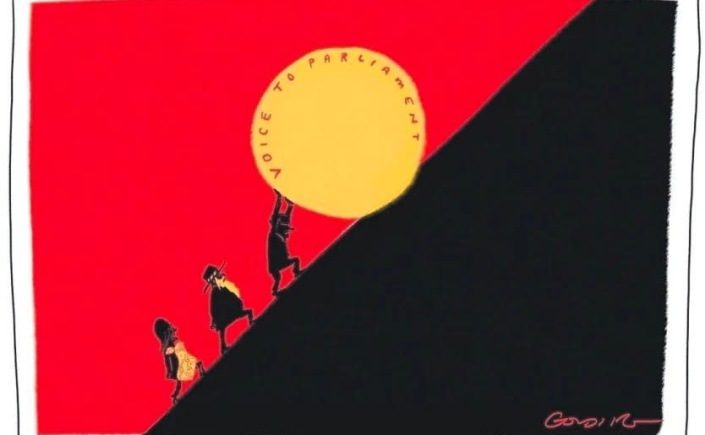

- Silencing The Voice – the Anatomy of a No voter

- Hopes and fears – the morning after the referendum for The Voice

- The Uluru Statement from the Heart

- A Voice crying in the wilderness

- We oughtn’t to fear an Indigenous Voice – but we do

- Warrior woman – the trials and triumphs of Marcia Langton

- If you can bear to hear the truth you’ve spoken … the emptiness of “No”

- Martin Sparrow’s Blues

- The Frontier Wars – Australia’s heart of darkness

- Dark Deeds in a Sunny Land – a poet’s memorial to a forgotten crime

- Farewell to Old England forever … reappraising The Fatal Shore

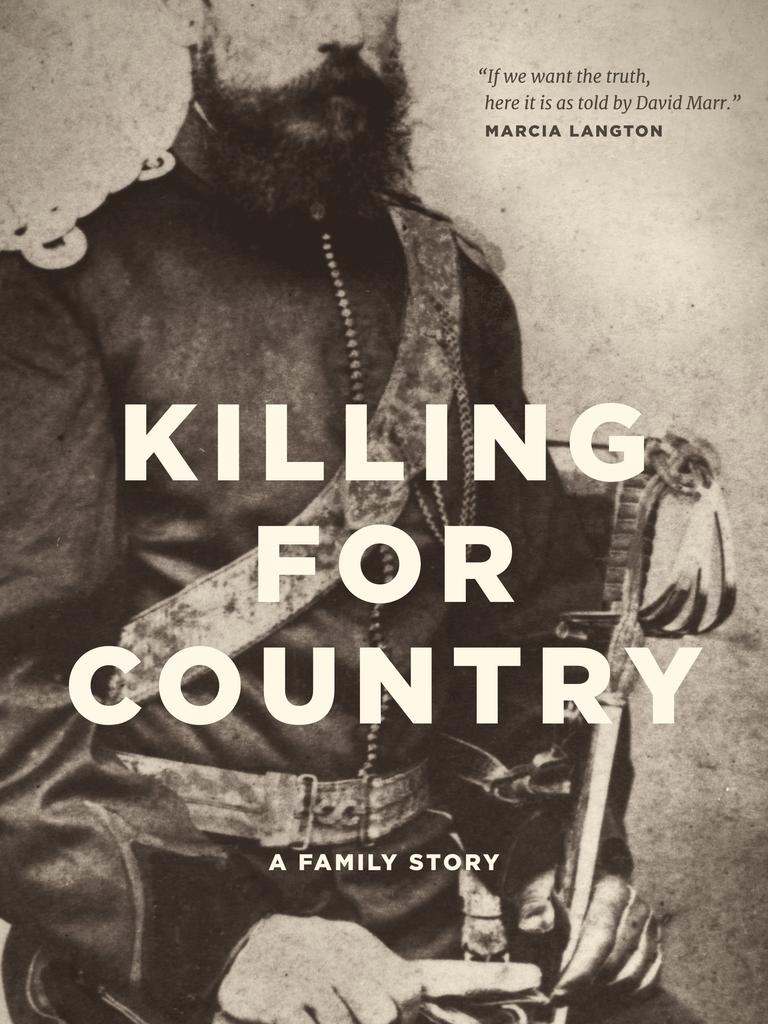

Healing country key in David Marr’s awful family history of murder and mayhem

Victoria Grieves Williams, The Weekend Australian. 16th March 2024

We live in a time of reckoning over the colonisation of the land mass that we now know as Australia. While British officials carefully avoided acknowledging that people existed on this continent prior to their arrival by adopting the infamous doctrine of terra nullius, many Australians are now re-examining the historical basis of their presence here. They know that they enjoy the material wealth and lifestyle of the lands they have come to call home and until recently there was no need to doubt, or be self-conscious, about Australia being “home”.

Yet there clearly were people here, and it was only the idea of an empty country that made it possible for agents of Empire, such as the Uhr brothers, ancestors of the journalist David Marr, to go about attempting to empty it.

Thus, settler colonials are having to come to terms with the fact that their ancestors were often murderous, criminal and racist, to what we may now understand as absurd and totally unnecessary lengths. And if they were not actually involved in these dirty deeds they were condoning them and even cheering them on. There were voices of dissent, but few are in the historical record. It is a ghastly story.

It is hardly surprising that Marr is now at the forefront, telling a family story about one of his great great grandparents and siblings that truly angers him. He has said that researching and writing this history is “partly an act of atonement and partly an act of rage”.

Marr is palpably angry. The book is written with an urgent passion, brave in what it reveals and unforgiving in the light it casts on bloody deeds.

I can only echo all that reviewers and commentators have said about this book. As Richard King said in his review (The Australian, October 13, 2023, republished below)this is “a magnificent achievement and a necessary intervention, on a subject that still divides Australia: the violent dispossession of its native peoples”.

It is what we have come to expect from a master journalist and storyteller who has a brilliant track record in publishing. The research is thorough and in this Marr was assisted by his partner Sebastian Tesoriero who connected with the joys of Trove, the online historical newspaper database. The search for the deeds of the Uhr brothers and the bloody swathe they and the Black Troopers cut through northern NSW and up through Queensland and into The Gulf country during the 19th century is satisfyingly forensic.

The aim of my essay is to place the book Killing for Country: A Family Story in the context of a process of truth telling. There is no doubt about the truth and veracity of this argument, that the frontier was a place of bloody mayhem and murder. Many Aboriginal people have always known this; the more naive of us have known at least since the early 1980s, with the publication of Geoffrey Blomfield’s groundbreaking Baal Belbora: The End of the Dancing and Henry Reynold’s important work, The Other Side of the Frontier.

What is left is to find a way to deal with this history in the best way possible, so as not to exacerbate social tensions and negatively impact race relations. My contention is that this is indeed a family story, to be resolved at that level.

On finishing reading the book I was left with the question: “What now?” What do we do with this awful history of murder and mayhem, the rage and need for atonement?

The first thing is to understand these events as history in a deeper sense, that is within a larger historical frame. Perhaps then we can understand what it is telling us of the true nature of human beings. This is the approach evident in Aboriginal cultural understandings of time and the ways in which conflicts are resolved.

Historians are now recognising that the colonial wars unleashed from the 16th century onwards are the first of the Great Wars. The death toll was immense: the Spanish conquest of the Americas from the 16th-18th centuries has an estimated death toll of 28 million. The British Empire, which held 24 per cent of the Earth’s total land area by 1920, wrought an estimated death toll of 100 million people. It was by far the largest empire in history and a source of great pride for those who tied their fortunes to it.

One could say that it was the fashion. Colonial wars were fought by European powers over the Indigenous people of the global south, not only in Australia but in Africa, Asia, South America and Mexico, India and China. The aim was to dispossess, enslave, destroy and claim all of what these people had of value, for the Empire. They were enormously successful.

No small part of this success is due to the specific kind of white masculinity that enabled the bloody conquest, that seemed to relish the lawless frontier and the opportunity to prove oneself.

This specific masculine ideal of violence as normative was nurtured and fostered as a part of the imperial ambitions of Britain, and thus built into colonial culture and politics. The workings of what the anthropologist Rita Laura Segato refers to as the masculine mandate whereby the libido is conscripted into providing constant proof that one truly is a man was the order of the day. Subservience to the masculine mandate is for both men and women the only way to exercise any power “power is expressed … exhibited and consolidated, as virile potency in a brutal form”.

Thus arises the pedagogy of cruelty through which Segato names all of what is manifest on human bodies to reduce them to things – violence, terror and cruelty.

In interviews, Marr has been emphatic that the people of the killing times are the same as those of today. It is my view that they are separated by huge social, cultural and political gaps and contexts that shape them. This has been a long debate in sociology, is it nature or nurture that produces certain kinds of people? In the case of settler colonial masculinist ideology, the society back in Britain was often shocked by the excessive violence of the frontier. They sought ways to curb them. Perhaps some realised they were a necessary evil and continued to fund and support them.

However, Marr has a point about the unchanged nature of people over time when you consider the murdered and missing Aboriginal women and children in Australia. For example, the crimes of the serial murderer Richard Dorrough against Aboriginal and Pacifica women. He, who perversely wanted his crimes to be known, can be seen as subservient to the masculinist mandate. There are many other perpetrators. The phenomenon of murdered and missing Aboriginal women and children is evidence of the continuation of the gendered conquest and pedagogy of cruelty in contemporary Australian society.

To enlarge on the macro view, the huge death toll in all of the worldwide wars since the 16th century has not seemed to make a dent on the continuing overpopulation of the Earth. We need to consider that huge hordes of Europeans moved out to the global south because they could not continue to live in home countries that were already overpopulated. The 18th century saw famines and food riots in Britain and France.

The colonial wars and subsequent mass migrations were a result of the very pressing need to find other lands on which to grow food and be able to live, as well as the search for the bounty that these lands could offer in timber, animal and mineral resources. While the idea of Manifest Destiny propelled settlers in North America, settlers in Australia were not untouched by this and also had the idea of an empty continent – therefore those who were there beforehand were not legitimate, had no rights, were not truly human.

And still yet – what now?

It’s important to understand that the way people see history, utilise it or deal with it varies according to cultural approaches. Aboriginal cultural understanding has it that our ancestors beyond the last two generations (that are usually in living memory) go back into eternal time where they are part of the paradigms for the proper human behaviour on Earth, also known as the Law. These paradigms are accessed through stories that are often attached to constellations and landforms. Eternal time is ever-present, it is here “running along beside us” enabling a connection through eruptions of eternal time into the present.

Eternal time then is connected to normal time in which we live, this is the “everywhen” that is often used to describe Aboriginal understandings of time. It is more than that, it is known as tjukurpa by Central Australian Anangu, and by other names elsewhere. Altogether it is the sacred, that is more easily accessed when in the state between dreaming and wakefulness. Hence the misnomer, the Dreaming.

If the Law is transgressed then people have to be held to account for their actions and the aim of a full and frank hearing is for people to be able to continue to live together in a good way. All involved are given an opportunity to speak their truth and an appropriate punishment is decided on and meted out. Once resolved, settled, these matters are never spoken of again. It is considered that the business is finished.

So, what now? The Yoorrook Commission in Victoria defines truth telling as the act of telling true history by listening to the experiences of First Peoples.

Marr has written this book as a contribution to the truth-telling process and this is, as he says, a family story. It holds the key to the important connections and relationships that can grow out of meeting with the “other” side. There are many descendants of the survivors of the killing times in north Queensland who have their own stories to tell. In some places the notorious Darcy Uhr is still in living memory.

What remains is for the Uhr family descendants to reach out and begin to make connections across the divide of a brutal history, for which no-one alive today is responsible or culpable, but for which we can feel deep regret and seek to heal the bonds that bind us as human beings. Our lives will all be so much better for it.

Victoria Grieves Williams is an historian and Warraimaay woman whose mother worked as a cook and housemaid at sheep stations at Brewarrina. She is based in New York

Killing for Country book review: examining the Native Police’s violent dispossession of Indigenous Australians

Richard King, The Australian. October 13th 2023

Running to almost half a thousand pages, prodigiously researched and immaculately written, David Marr’s Killing for Country: A Family Story is surely one of the books of the year. Modestly described as a “family story”, it is in fact as solid a work of history as one could hope to find on the shelves. Clearly, the book holds enormous significance – enormous personal significance – for its author. But Marr brings the same forensic approach to this narrative of the frontier wars as he did to his celebrated biography of Patrick White, to his monographs of Tony Abbott and George Pell, and to his indispensable account of the Tampa/Children Overboard affair and Pacific Solution, Dark Victory.

It is a magnificent achievement, and a necessary intervention, on a subject that still divides Australia: the violent dispossession of its native peoples.

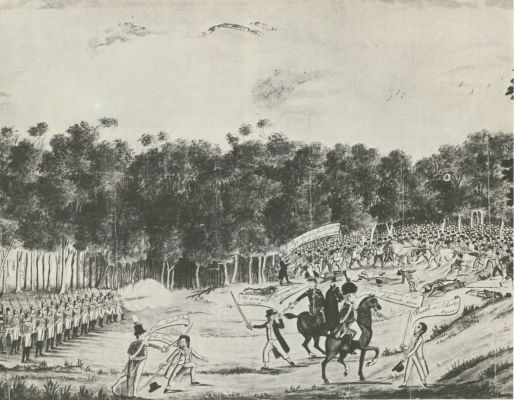

It was the discovery that his great-great-grandfather had served with the Native Police that set Marr off on this bold endeavour. The son of Edmund Blucher Uhr, scion of a poorly connected family with pretensions to Irish nobility, Reginald Uhr and his brother D’arcy were both officers in this notorious outfit, which cleared land of its Aboriginal owners at the behest of the squattocracy, avenging attacks on farmers’ livestock and “dispersing” troublesome gatherings. “Dispersing” was a euphemism, of course, but so too was “police”: as even contemporaries understood, the NP was a quasi-military unit, not a tool of law enforcement. It’s estimated that over 60 years it murdered more than 10,000 people (Marr says a “cautious interpretation” of these figures has seen estimates rise from 10,000 to 20,000 and now to more than 40,000).

The NP began its campaign of killing in the Darling Downs in 1848, but its brutality reached its feverish peak as it moved north in the 1860s, in the wake of Queensland’s break from New South Wales. Its campaigns were characterised by a basic asymmetry, as the belligerents in the frontier wars operated according to different principles: the Indigenous peoples saw themselves as redressing grievances through evening up the score, while white retaliation was inordinate. A pattern quickly established itself. Colonial expansion led to Indigenous resistance, which led in turn to further dispersals. Notwithstanding that these acts of violence were often met with disapproval by the colonial authorities, the indulgence shown towards them was baked in, in a way that gives the lie to the idea that the NP was dispensing justice. The reality is that it was clearing the land of black bodies.

This picture is complicated by the fact that the NP comprised units of eight to ten such bodies under the command of a single white one. But in Marr’s telling, this organisational structure was something of a genius-stroke, in that it drew on the multinational nature of the Indigenous population and on the profound connection to place – to country – that characterises Indigenous society in general. As he puts it:

“What made them strange and dangerous to each other was being away from their own country, the country that made them who they were. Here was a deadly conundrum. While officially denying their attachment to land, colonial authorities would rely on that profound attachment – and the divisions it provoked – to raise a black force that would strip them of their country.”

Such an arrangement also allowed the NP to characterise the murdering as what a US Republican might call “black on black” violence. The recruitment of Aboriginal men gave white officers a handy alibi when questioned by their superiors.

Why would the killers need an alibi? The question may sound ridiculous, but conservative history warriors who criticise histories such as these, will often suggest that their authors are guilty of projecting modern values backwards (this is the so-called “black armband” charge). But what emerges from these grisly pages, and from the accounts of the contemporary outrage directed against the clearances, is a picture of a system of “justice” founded on a gargantuan hypocrisy – hypocrisy being the compliment that vice implicitly pays to virtue. In other words, many of the men in this “story” knew full well that they were involved in an immoral undertaking, and commentary that attempts to downplay this reality is, itself, unhistorical. This is not to say that the picture is simple: history is a tragedy, not a morality play. It is simply to agree with the author that if it is possible to feel pride in one’s country, it should be possible to feel ashamed of it too.

Marr does not make a show of such feelings. In his television appearances, he will often adopt the sort of demeanour that (I imagine) sends conservatives round the bend: the more-in-sorrow-than-in-anger eyes; the casual, cruising exasperation at the politics he doesn’t share, and is, therefore, self-evidently preposterous. But here the tone is even and controlled. One notes the slightly ironic adjectives and the occasionally sardonic descriptions. (“He recruited blacks as guides. He also shot blacks who stood in his way. Somerville was a genial and unscrupulous gentleman of the warrior class.”) But in general he lets the material speak for itself. Goodness knows, there’s plenty of it. As Marr notes – again, a little sardonically – one good thing about the colonists is that they wrote plenty of fine letters home.

The attitudes evinced in those letters, or the language in which those attitudes are couched, will no doubt distress most contemporary readers, and it would be vacuously polemical to assert that nothing’s changed. It has. Nevertheless, it is the achievement of this book to invite us to reflect on the many connections between contemporary Australia and its bloody past. That past is not a foreign country. It just speaks in thicker accents than we are used to.

Richard King is an author and critic. His most recent book is Here Be Monsters: Is Technology Reducing Our Humanity? (Monash University Press)

Killing for Country: A Family Story

By David Marr

Black Inc, Nonfiction

$39.99; 468pp