If you could hear, at every jolt, the blood

Come gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs,

Obscene as cancer, bitter as the cud

Of vile, incurable sores on innocent tongues,

My friend, you would not tell with such high zest

To children ardent for some desperate glory,

The old Lie: Dulce et decorum est

Pro patria mori.

Poet Wilfred Owen died on 4 November 1918 – seven days before the guns fell silent in the war that people though would end all wars – as it turned out, the Treaty of Versailles became the peace that ended all peace.

That “old Lie,” from which his most famous poem Dulce et Decorum Est takes its title, comes from the Roman poet Horace. No bitter irony was intended, though, as Horace beseeched Romans to embrace the cleansing fire of a noble death.

In a brief article in the e-zine Quillette, titled The End of War Poetry, Simon British stand-up comic, satirist, writer, and broadcaster Simon Evans wrote: “Privately, I still find the idea of young men gladly ploughing themselves back into the earth of their homeland unbearably moving. But after Owen, recreating such an ecstatic embrace of death in the service of a greater cause became as impossible as nailing Christ back onto the cross, or rather, nailing that cross back onto the wall”.

As Evans observes, the First World War at least gave us some of the most cherished and painfully beautiful verse in our history. “Poetry bubbled from the trenches in France as abundantly as methane, oaths, and blisters … [and] central to earlier war poetry was the tension between the terror, devastation, and death on one hand, and the opportunity for virtues like loyalty and honour on the other”.

Contemplating explanations, he writes that a junior officer’s prospects of survival were considerably worse than those of his men. According to one account, as little as six weeks. That might explain the poetry. Such a violently diminished life expectancy must have focused the mind wonderfully. World War Two was—on that score at least—considerably more democratic and egalitarian … By 1939, the culture had shifted for officers and men alike. The practice of soldiers carrying a slim volume of Browning or Keats, and of aspiring to emulate whoever was in their pockets, had passed. In 1914, the available persona of the poet was still vital—or seems so now, in sepia vignette. He was the sensitive man quietly scratching a wet match against sandpaper and putting it to a candle, careful not to wake the slumbering cattle. Ignoring the grotesque shadows that leapt in the dug-out, he would unfold his notebook, its neat ruled lines like trenches in which the words would hunker, later pressed against his breast as a Talisman once returned to his pocket. Working slowly through his exhaustion and his tobacco ration, setting down his impressions in bottled ink, striving with purpose to resolve the lunacy and the oceans of spilt blood just a few dark yards away”.

Second lieutenant Wilfred Owen, 25 years of age, was one of the last to die in a war that claimed 20 million dead and 20 million injured. At least for the past half-century, his poems have served as a prism through which the so-called Great War is viewed. But, despite being anthologised by his friend Siegfried Sassoon in 1920 and Edmund Blunden a decade later, they did not enter popular parlance until pacifist composer Benjamin Britten incorporated some of Owen’s most potent verses in his War Requiem, written for the 1962 inauguration of the restored Coventry Cathedral

Owen entered Britain’s national curriculum during the 1960s, and eventually the high school curricula of Commonwealth nations, which is where I first encountered him – and I was shocked by his visceral descriptions and implicit denunciations of war. He did not dwell on the causes but seemed to suggest that the sheer awfulness of military conflict between nations had stripped away all justifications.

“There had been many wars before, of course, but none where the poet was the soldier and, therefore, the intimate witness. This war was the rendering of wounds, both flesh and spiritual, by words”.

We republish below two excellent articles on Wilfred Owen and the poets of the First World War.

Othe posts in In That Howling Infinite: Dulce et Decorum est – the death of Wilfred Owen. A Son Goes To War – the grief of Rudyard Kipling and November 1918 – the counterfeit peace

Bent double, like old beggars under sacks,

Knock-kneed, coughing like hags, we cursed through sludge,

Till on the haunting flares we turned our backs,

And towards our distant rest began to trudge.

Men marched asleep. Many had lost their boots,

But limped on, blood-shod. All went lame; all blind;

Drunk with fatigue; deaf even to the hoots

Of gas-shells dropping softly behind.

Gas! GAS! Quick, boys!—An ecstasy of fumbling

Fitting the clumsy helmets just in time,

But someone still was yelling out and stumbling

And flound’ring like a man in fire or lime.—

Dim through the misty panes and thick green light,

As under a green sea, I saw him drowning.

In all my dreams before my helpless sight,

He plunges at me, guttering, choking, drowning.

If in some smothering dreams, you too could pace

Behind the wagon that we flung him in,

And watch the white eyes writhing in his face,

His hanging face, like a devil’s sick of sin;

If you could hear, at every jolt, the blood

Come gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs,

Obscene as cancer, bitter as the cud

Of vile, incurable sores on innocent tongues,—

My friend, you would not tell with such high zest

To children ardent for some desperate glory,

The old Lie: Dulce et decorum est

Pro patria mori.

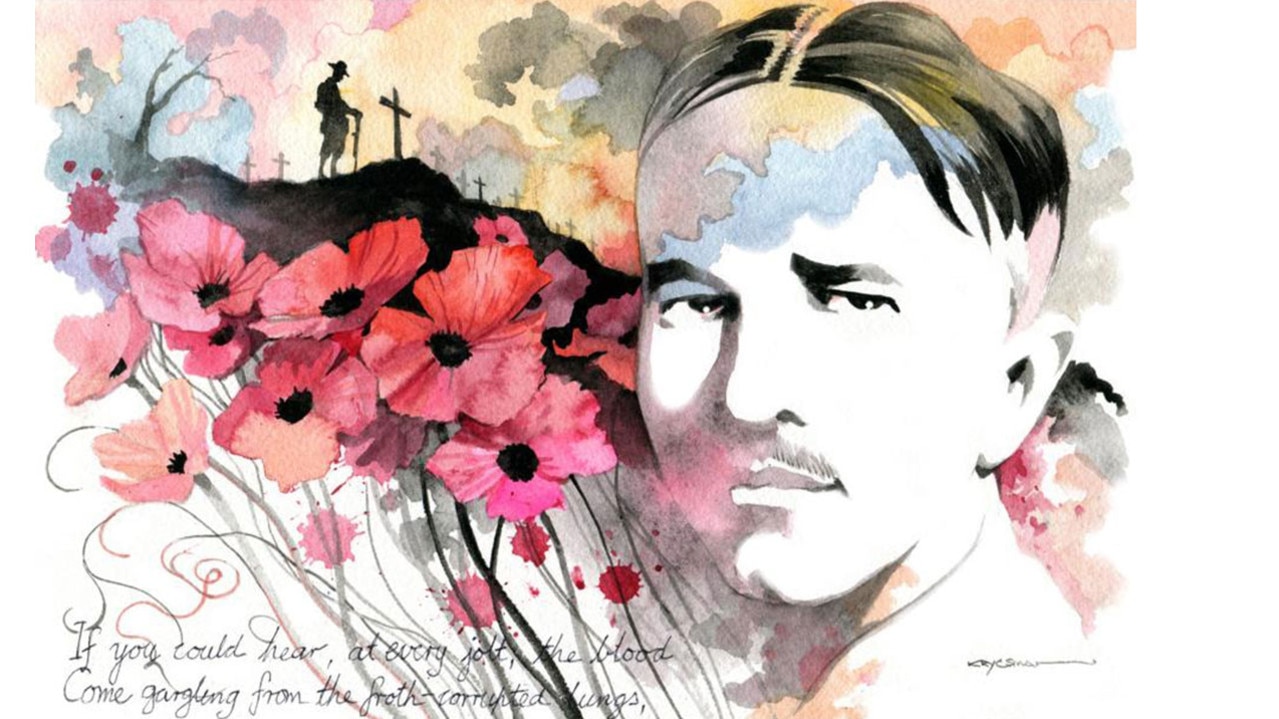

War poet Wilfred Owen: sweet and honourable lie

Artwork: Sturt Krygsman.

Mahir Ali, Weekend Australian, 10th November 2018

During a visit to London in 1920, Bengali poet, philosopher and polemicist Rabindranath Tagore received an unexpected letter from a Mrs Susan Owen. She wished to share some information about her favourite son.

“It is nearly two years ago, that my dear eldest son went out to the War for the last time,” she wrote, “and the day he said Goodbye to me … my poet son said these wonderful words of yours … ‘when I leave, let these be my parting words: what my eyes have seen, what my life received, are unsurpassable’. And when his pocket book came back to me — I found these words written in his dear writing — with your name beneath.”

Tagore was something of a celebrity in Britain at the time, a white-bearded Indian sage who bore a resemblance to the then recently deceased Leo Tolstoy. He had won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1913 on the strength, essentially, of Gitanjali, a collection of poetry he had translated from the original Bengali with the assistance of William Butler Yeats, which is the source for the aphorism that appealed to Owen’s son. That son, Wilfred, is likely to have perceived rather differently from Tagore the context of what each of them considered “unsurpassable”.

It is equally likely that the young Englishman was unfamiliar with Tagore’s thought-provoking critique of nationalism as well as the poem, composed on the last day of the 19th century, that demonstrates a remarkable prescience about the maelstrom that sneaked up on Europe shortly afterwards:

The last sun of the century sets amidst the blood red clouds of the West and the whirlwind of hatred The naked passion of self-love of Nations, in its drunken delirium of greed, is dancing to the clash of steel and the howling verses of vengeance The hungry self of Nation shall burst in a violence of fury from its own shameless feeding For it has made the world its food …

A plate from Poems by Wilfred Owen (1920)

Wilfred Owen’s final foray into that maelstrom came in August 1918. He won a Military Cross shortly afterwards. But while the Armistice Day bells pealed on November 11, his family received a telegram informing them that Wilfred had been killed a week earlier — 100 years ago last Sunday — while leading the men under his command across the Sambre-Oise canal at Ors.

The second lieutenant was 25, his longevity abbreviated by a year even in comparison with the life span of his favourite predecessor poet, John Keats.

Unlike all too many of his contemporaries, though, Owen did not exactly die in vain. At least for the past half-century, his poems have served as a prism through which the so-called Great War is viewed. But, despite being anthologised by his friend Siegfried Sassoon in 1920 and Edmund Blunden a decade later, they did not enter popular parlance until pacifist composer Benjamin Britten incorporated some of Owen’s most potent verses in his War Requiem, written for the 1962 inauguration of the restored Coventry Cathedral.

Coincidentally, about the same time, a fellow composer appropriated a contemporary young poet’s verses as the centrepiece of his 13th symphony: Dmitri Shostakovich immortalised Yevgeny Yevtushenko’s poem Babi Yar, which catapults from a reflection on an egregiously atrocious component of the Judeocide that accompanied World War II into a searing condemnation of anti-Semitism. It also serves as a reminder that the “war to end all wars” not only did nothing of the kind but in fact sowed the seeds for an even more outrageous bloodbath.

Owen entered Britain’s national curriculum during the 1960s, and eventually the curricula of Commonwealth nations, which is where I first encountered him and was blown away by his visceral descriptions and implicit denunciations of war. He did not dwell on the causes but seemed to suggest that the sheer awfulness of military conflict between nations stripped away all justifications.

The alliteration and onomatopoeia of the sonnet Anthem for Doomed Youth made a powerful impression, but so did the realisation that “those who die as cattle” were by no means restricted to Gallipoli or the Somme, and that “the stuttering rifles’ rapid rattle” continued to “patter out” all too many “hasty orisons”.

Dulce et Decorum Est stands out not only for nailing Horace’s destructive untruth about the value of patriotic sacrifice but also because gas attacks against unsuspecting victims remain par for the course on Middle Eastern battlefields — notably in Syria, where chlorine, used to such devastating effect in World War I, continues to serve as a favourite weapon for the Assad regime and some of its opponents.

Owen pictured a gas attack on a retreating column of comrades in which just one fails to fit “the clumsy (helmet) just in time”. “In all my dreams, before my helpless sight, / He plunges at me, guttering, choking, drowning,” he declares, comparing the soldier’s “hanging face” to “the devil’s sick of sin”, before going in for the kill, so to speak:

If you could hear, at every jolt, the blood

Come gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs,

Obscene as cancer, bitter as the cud

Of vile, incurable sores on innocent tongues,

My friend, you would not tell with such high zest

To children ardent for some desperate glory,

The old Lie: Dulce et decorum est

Pro patria mori.

The Latin translates as “it is sweet and honourable to die for one’s country”, and Owen’s oeuvre offers incontrovertible evidence to the contrary.

He goes much further in Futility, whose title has been cited by scholars as a key to framing contemporary conceptions of the conflict. Yet in this poem Owen is questioning not just the war but the very point of life on earth. Again, it’s based on a single casualty, a human being the sun can no longer manage to revive after having roused it for so many years. “Was it for this the clay grew tall?” the poet asks: “O what made fatuous sunbeams toil / To break earth’s sleep at all?”

Then there’s Strange Meeting, a reinforcement of the trope whereby warriors in the battlefield come up against a foe who is a doppelganger, as in Bob Dylan’s relatively obscure early song John Brown, where the narrator informs his mother: “But the thing that scared me most was when my enemy came close / And I saw that his face looked just like mine.” In Owen’s case, the resemblance is not physical but spiritual, in a poem replete with the half-rhymes that distinguished his style; groined/groaned, moan/mourn, spoiled/spilled, mystery/mastery and so on.

He escapes “down some profound dull tunnel” to a “sullen hall”, and by the “dead smile” of an inmate who greets him “with piteous recognition in fixed eyes” knows that “we stood in Hell”. Back in the day, those social democrats (synonymous at the time with socialists and communists) who had not fallen into the patriotic trap tended to describe a bayonet as “a weapon with a worker at both ends”. Owen sees a blade with a poet at both ends: “Whatever hope is yours, / Was my life also,” his new acquaintance tells him. “I went hunting wild / After the wildest beauty in the world … For by my glee might many men have laughed, / And of my weeping something had been left, / Which must die now. I mean the truth untold, / The pity of war, the pity war distilled.” The poem concludes thus:

I am the enemy you killed, my friend.

I knew you in this dark: for so you frowned

Yesterday through me as you jabbed and killed.

I parried; but my hands were loath and cold.

Let us sleep now …

In The Parable of the Old Man and the Young, meanwhile, Owen subverts a key narrative from the Old Testament to formulate his angst. An angel intervenes as Abraham prepares to murder his firstborn, Isaac, and offers a ram instead. “But the old man would not so, but slew his son / And half the seed of Europe one by one.” It’s unlikely he would have quarrelled with American “singer-journalist” Phil Ochs’s declaration almost a half-century later: “It’s always the old to lead us to the war / It’s always the young to fall / Now look at all we’ve won with the sabre and the gun / Tell me is it worth it all …”

It wasn’t, of course, just the seed of Europe that perished in the early 20th-century carnage. We never cease to be reminded how Australia answered the call — and paid proportionately a higher price than any other country in what purportedly served as a nation-building cull. Its effort was voluntary, a precursor to almost every Western-waged war through the 20th century and beyond — from Korea to Vietnam, Afghanistan and Iraq — to which our nation has contributed its young blood, chiefly as a means of ingratiating itself with its imperial “protectors”, and partly by regurgitating “the old Lie”.

But plenty of countries that were still colonies in 1914 also contributed their spawn — a million men in India’s case, as reflected in Trench Brothers, a play premiered in Brighton a couple of weeks ago. Besides, the Ottoman Empire was a participant, on Germany’s side, in the Great War, so substantial parts of the Middle East were not immune to the conflict. And the war’s last shots were fired in southern Africa, where the imperial urge had drawn several European nations, including Britain and Germany.

Owen wasn’t a conscientious objector by nature. As a Shropshire lad he was deeply religious, to the extent that initially the liturgy trumped his second love, poetry, and for a time he was expected to join the clergy. But better sense prevailed, and he was teaching in France when the war broke out. He returned home, joined up and underwent training, but wasn’t cast into the cauldron until January 1917. He was back home by midsummer, after having been blown out of a trench into a well. He recuperated at Craiglockhart Hospital near Edinburgh, a facility for the shell-shocked, or those with what today would be designated as post-traumatic stress disorder.

It was there that he encountered Sassoon, an army captain who had been dispatched partly as means of silencing his increasingly trenchant anti-war propaganda.

Owen was familiar with the poetry of Sassoon, who was six years older, and tentatively approached him for an autograph before sharing his own efforts at wartime verse. In response, Sassoon combined constructive criticism with a great deal of encouragement, and soon enough the pent-up poems began pouring out of Owen.

Almost all of his best-known poems surfaced during the year or so between then and his demise, most of them emotions recollected during the relative tranquillity of sojourns in his homeland. Among the first was The Send-Off, in which he compares soldiers on an outward bound train, their “faces grimly gay”, with “wrongs hushed-up”. He goes on to ask: “Shall they return to beating of great bells / In wild train-loads? / A few, a few, to few for drums and yells, // May creep back, silent, to village wells, / Up half-known roads.”

In Exposure, we encounter frozen corpses as: “The burying-party, picks and shovels in shaking grasp, / Pause over half-known faces. All their eyes are ice, / But nothing happens.” In Mental Cases, there is the devastating verse: “Surely we have perished/ Sleeping, and walk hell; but who these hellish?”

In a draft preface to a planned 1919 collection of his verse, Owen wrote: “Above all, this book is not concerned with Poetry. The subject of it is War, and the pity of War. The Poetry is in the pity. Yet these elegies are to this generation in no sense consolatory. They may be to the next. All the poet can do to-day is to warn.’’

Less than 30 years later, Wilfred Burchett, the Australian who became the first Western journalist to witness the devastation of Hiroshima, prefaced his account with the words: “I write this as a warning to the world.”

Unheeded warnings remain one of the driving forces of history’s chariot wheels, clogged as they are with much blood, but who can sensibly argue that they ought not to have been articulated? Who can say when we will ever learn, but it’s unlikely Owen would have disputed his contemporary Robert Graves’s reflection on November 11, 1918:

When the days of rejoicing are over,

When the flags are stowed safely away,

They will dream of another ‘War to end Wars’

And another wild Armistice Day

Poets in action: How writers captured the horrors of the Great War

Warwick McFadyen, Sydney Morning Herald 2nd

One hundred years ago today, Wilfred Owen, poet and soldier, had 24 hours to live. On November 4, 1918, Owen and his men were trying to cross a canal near Ors in France. As Owen was walking among his men, offering encouragement, German machine guns burst into action. Owen fell. He was one of the last to die in a war that claimed 20 million dead and 20 million injured. He was promoted to lieutenant the next day.

In the cruellest twist, Owen’s mother in Shrewsbury received the telegram of his death on November 11, Armistice Day, as the bells were ringing for peace.

Poetry would mourn the loss of a singular talent, whose star was just beginning to light the sky. Owen had seen but a handful of his poems in print before his death, aged 25. He had written all we have, in little more than 12 months, from August 1917.

The first collection, edited by Siegfried Sassoon, was published in 1920, and then in 1931 appeared an expanded collection. In the latter edition, editor Edmund Blunden wrote that Owen “was a poet without classifications of war and peace. Had he lived, his humanity would have continued to encounter great and moving themes, the painful sometimes, sometimes the beautiful, and his art would have matched his vision.”

Apart from what are regarded as classics such as Anthem for Doomed Youth and Dulce Et Decorum Est, it is Owen’s preface to the collection that is as famous as the poems: “Above all I am not concerned with Poetry/ My subject is War, and the pity of War/ The Poetry is in the pity/ Yet these elegies are to this generation in no sense consolatory/ They may be to the next/ All a poet can do today is warn/ That is why the true Poets must be truthful.”

The First World War was a charnel house. A generation of young men marched to the front, often singing and with cheerful abandon, at least in the beginning, to be slaughtered. Poetry, unlike any time before or since, was the vehicle for their voices and those of bystanders. At first, it was celebratory, but as the days of carnage rolled on and on, truth came to be heard.

There had been many wars before, of course, but none where the poet was the soldier and, therefore, the intimate witness. This war was the rendering of wounds, both flesh and spiritual, by words.

Robert Giddings, in The War Poets, writes that “before 1914, when poets dealt with war it was to render it exotically or historically removed from immediate experience. War, in the hands of Macaulay, Tennyson, Arnold, Newboult and Aytoun, had all the conviction of modern television costume drama. There were two outstanding exceptions – Rudyard Kipling and Thomas Hardy.”

The primacy of the poet in people’s lives a century ago can be seen in the immediate bringing into action of writers to support war aims. On September 2, 1914, only five weeks after war was declared, The Times, published a letter from the Poet Laureate, Robert Bridges, in which he likened the good soldiers of empire fighting the Devil. The image of the soldier as Christ was popular in these early stages, as was the theory that war was a necessary purification of nations. The government’s Propaganda Bureau enlisted writers such as Arthur Conan Doyle and G.K. Chesterton to promote Britain’s war aims. It took the pre-eminent war poet Sassoon to use the figure of Christ in a heightened awareness of spirit, flesh and suffering that had nothing to do with patriotism.

Professor Tim Kendall, in Poetry of the First World War, writes that during the war “poetry became established as the barometer for the nation’s values: the greater the civilisation, the greater its poetic heritage”. He believes that the “close identification of war poetry with a British national character persists to the present day”.

As to Australia’s war effort in poetry, despite more than 415,000 men enlisting (from a population of fewer than 5 million) with 60,000 killed and more than 150,000 injured or taken prisoner, the results hardly trouble the margins of anthologies.

As Geoff Page noted in Shadows from Fire: Poems and Photographs of Australians in the Great War, the literary efforts of those Australians with direct experience in the war were less than memorable. His intention with the book was to juxtapose recent poems “with Australians poems actually written during the conflict”.

“On closer examination, however, I found the quality of these latter poems to be depressingly low – especially when contrasted with those of the English war poets: Owen, Sassoon and Rosenberg . . . It rapidly became apparent that a much more appropriate and powerful record of the conflict could be found among the contemporary photographs held by the Australian War Memorial. These speak with a directness and truth seldom attempted, at that time, by our poets.”

By the end of 1914, two anthologies of wartime verse had been published. Many poets in the early years were no more than writers of patriotic doggerel. The Georgian movement, of pastoral whimsy, and gentle beauty, had found a cause in which to celebrate England. The modernism that had slowly been growing in Europe had not permeated English literary minds, but in the aftermath of the war it blossomed, seen no more so than in T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land, published in 1922.

Dominic Hibberd and John Onions, in their book The Winter of the World, cite the work of historian Catherine Reilly in which she records 2225 British writers who experienced the war, and published poems of their experience. A quarter of the writers were women. By contrast Westminster Abbey honours 16 poets of WWI, all men: Richard Aldington, Laurence Binyon, Edmund Blunden, Rupert Brooke (“If I should die, think only this of me: That there’s some corner of a foreign field that is for ever England”), Wilfred Gibson, Robert Graves, Julian Grenfell, Ivor Gurney, David Jones, Robert Nichols, Owen, Sir Herbert Read, Isaac Rosenberg, Sassoon, Charles Sorley and Edward Thomas.

Since suffering and death were universal there were no frontiers in the writing of it, geographically, with Austrian Georg Trakl, German Alfred Lichtenstein, Italian Giuseppe Ungaretti, Canadian John McCrae and Frenchmen Guillaume Apollinaire and Henri Barbusse, or in gender, Edith Sitwell, Margaret Sackville, Alice Meynell and Vera Brittain, whose Testament of Youth is regarded as a masterpiece of the period.

This was the flowering that has not been captured again. The poets of the Second World War do not go much beyond Keith Douglas and Paul Celan.

It seems curious and strange now, but the biggest barricade to the acceptance of the war poets in the immediate years after came from the towering figure of Nobel Laureate W.B. Yeats.

The Oxford Book of Modern Verse 1892-1935, published in 1936, was edited by Yeats. It contained nothing from the war. Yeats defended his decision thus: “In poems that had for a time considerable fame, written in the first person, they made suffering their own. I have rejected these poems . . . passive suffering is not a theme for poetry. In all the great tragedies, tragedy is a joy to the man who dies, in Greece the tragic chorus danced. If war is necessary, or necessary in our time and place, it is best to forget its suffering, as we do the discomforts of fever, remembering our comfort at midnight when our temperature fell.”

Yeats was wrong, comprehensively so. But the glory was that Owen, Sassoon, Thomas, Rosenberg et al showed that there was art in death and suffering. The war poets found in the desolation of France and in the ruined bodies and spirits in hospital wards, a voice transcendent. Theirs was the fundamental expression of what it meant – still means – to be human. And there was a warning, but as history turned, no one was listening.

“Out there, we’ve walked quite friendly up to death;/ Sat down and eaten with him, cool and bland,/ Pardoned his spilling mess tins in our hand./ We’ve sniffed the green thick odour of his breath,/ Our eyes wept, but our courage didn’t writhe./ He’s spat at us with bullets and he’s coughed/ Shrapnel. We chorused when he sang aloft;/ We whistled while he shaved us with his scythe.” (The Next War, Wilfred Owen)

Siegfried Sassoon wrote in his diary of November 11: “The war is ended. It is impossible to realise. I got to London about 6.30 and found masses of people in streets and congested Tubes, all waving flags and making fools of themselves – an outburst of mob patriotism. It was a wretched wet night, and very mild. It is a loathsome ending to the loathsome tragedy of the last four years.”