These were our children who died for our lands: they were dear in our sight.

We have only the memory left of their home-treasured sayings and laughter.

The price of our loss shall be paid to our hands, not another’s hereafter.

Neither the Alien nor Priest shall decide on it. That is our right.

But who shall return us the children?

In an excellent article commissioned by Vanity Fair in 1997, and republished below, the late author and celebrated contrarian Christopher Hitchens told a poignant story of the British poet Rudyard Kipling and the death in battle of his son John in France in 1915.

He prefaced his tale with a scene-setting prelude:

“A ghost is something that is dead but won’t lie down. Those who were slaughtered between 1914 and 1918 are still in our midst to an astonishing degree. On the first day of the Battle of the Somme, in July 1916, the British alone posted more killed and wounded than appear on the whole of the Vietnam memorial. In the Battle of Verdun, which began the preceding February, 675,000 lives were lost. Between them, Britain, France, the United States, Germany, Turkey, and Russia sacrificed at least 10 million soldiers. And this is to say nothing of civilian losses. Out of the resulting chaos and misery came the avenging forces of Fascism and Stalinism”.

Hitchens referred to many of Kipling’s poems in his article, particularly those relating to the First World War, the jingoistic ones that greeted, indeed welcomed the beginning of hostilities, and the melancholy ones that marked their end, reflecting his personal loss and also that of tens of thousands of other parents and partners and siblings.

He does not mention however, Kipling’s post war short story, The Gardener, which directly addresses the grief and the loss felt by so many. John Kipling’s body was never found, but the poet and his wife made fruitless inquiries as to his fate and his whereabouts and, as patrons of the War Graves Commission, made many visits to the military cemeteries of Flanders.

British War Cemetery in Flanders

The Gardener tells the tale of a woman’s search for a loved one who fell. It is told from the woman’s point of view. Is the missing solder her her nephew or or son? Kipling is deliberately ambiguous, reflecting perhaps the morality of his times. It is up to the reader to draw his or her own conclusion. The ending is likewise opaque. Unlike the author, she does indeed find her lost soldier, but only with the the help of a kind, anonymous stranger. Again it is for the reader to judge – although Kipling himself left little room for ambiguity. The story ends in some editions with an asterisk in the text that links to a line from the Bible, John 20:15: “Jesus saith unto her, ‘Woman, why weepest thou; whom seekest thou?’ She, supposing him to be the gardener, saith unto him, ‘Sir, if thou has borne him hence, tell me where thou has laid him.’”

The Gardener is is republished below, following Hitchens’ article.

In 1992 the Commonwealth War Graves Commission announced that it had identified an Irish Guards lieutenant’s body in St Mary’s Advanced Dressing Station (ADS) near Loos as that of John Kipling. Seven years later authors Tonie and Valmai Holt published a book My Boy Jack, named for Kipling’s poem, which disputed that the body in St Mary’s ADS is that of John Kipling. They based their case on two separate arguments: John Kipling was a 2nd lieutenant not a lieutenant when he died, and his body was found six kilometres away from where he fell. My Boy Jack is the story of a father in pursuit oh his son whose body was never found. Although Kipling’s poem, quoted by Hitchens in his piece, was a tribute to a 16 year old sailor, Jack Cornwell, who perished at his post during the Battle of Jutland in 1915, becoming the youngest recipient of the Victoria Cross, the book and the play and film adapted from it tell the story of Kipling and his son.

For all their money, fame and connections, the Kiplings were just another one of the 415,325 British and Irish families whose sons were killed during the first World War and were left with no place to grieve. It was Kipling who gave us the headstone words “known unto God”.

The Death of Son

American novelist Scott Spencer wrote about The Gardener in an opinion piece in The Atlantic in June 2017. He wrote:

“It’s hard to talk about a Kipling story without talking about Kipling, a shameless apologist for English imperialism who coined the phrase “the white man’s burden” and who was the first person to refer to the Germans as Huns. He was a man who glorified war without ever having fought in one—and that’s where you get into the intense mix of grief and shame that Kipling surely brought to this story. Like so many young men at the time, Kipling’s son John was frantic to get into the war, but was at first turned down for duty because of weak eyes. His father, a person of almost unimaginable influence for a writer—the youngest Nobel prize winner, a darling of the English military and the British aristocracy—intervened, greasing the wheels and getting his son into the war, with the result that the younger Kipling was killed almost instantly.

When all hope of finding his son alive or dead was at last abandoned, Kipling, in his famous “Epitaphs of the War,” wrote: “If any question why we died / tell them, because our fathers lied.” You sense this same self-implication in “The Gardener.” After all, why were those boys clamoring to go over and get themselves blown up like that? Because a culture had been created that glorified that military sacrifice, and encouraged you to feel that your life was incomplete if you hadn’t fought for your country. Millions of English boys like John Kipling (and like the fictional Michael) were raised in this atmosphere of almost rabid patriotism, an atmosphere that Rudyard Kipling had not only exploited in his writing but also helped to create. And when war was declared, some six million Englishmen, many of them little more than boys, were put to battle; nearly one million were killed, and still more were grievously injured.

The Gardener gets to the grief and futility Kipling must have felt by the end of it all.

In Kipling’s case, he never found that grave. But in Helen’s case, Jesus leads her right to it. Was Kipling himself looking for an expiation of the shame he felt for his share of the responsibility for the loss of his son in such a useless and meaningless way—and all the other hundreds of thousands of wartime deaths? It could be said that all armed conflicts are a ludicrous and shameful waste of lives, but World War I has a special place in the history of futility—a war without clear purpose, a war whose resolution would ultimately make the world a far worse place. What moves me in “The Gardener” is the way Kipling so artfully seeks relief from his own complicity in the myths that led to war

On his 18th birthday, Michael enlists in the British Army, and is slaughtered shortly after, his body covered over by debris and unable to be located. Much, much later Michael’s body is discovered and finally Helen is able to travel to his grave in a military cemetery in France to pay her last respects. The story, which is not very long, moves with the efficiency of a fable—years go by in a half sentence. The tone is almost matter-of-fact, but we are being set up by a master craftsman for the story’s devastating climactic scene. Helen wanders through a vast expanse of graves, all of them marked with a number, not a name, each individual soldier located only through a painstaking process of record-keeping. (It was Kipling who lifted the phrase “known unto God,” out of the Bible and into the cemeteries and the monuments for unknown soldiers.) Then, while searching the endless sea of crosses, helpless, Helen comes upon a gardener. Kipling describes the exchange this way:

[The gardener] rose at her approach and without prelude or salutation asked: “Who are you looking for?”

“Lieutenant Michael Turrell—my nephew,” said Helen slowly and word for word, as she had many thousands of times in her life.

The man lifted his eyes and looked at her with infinite compassion before he turned from the fresh-sown grass toward the naked black crosses.

“Come with me,” he said, “and I will show you where your son lies.”

“The man lifted his eyes and looked at her with infinite compassion before he turned from the fresh-sown grass toward the naked black crosses.

“Come with me”, he said, “and I will show you where your son lies.”

The story ends in some editions with an asterisk in the text that links to a line from the Bible, John 20:15: “Jesus saith unto her, ‘Woman, why weepest thou; whom seekest thou?’ She, supposing him to be the gardener, saith unto him, ‘Sir, if thou has borne him hence, tell me where thou has laid him.’”

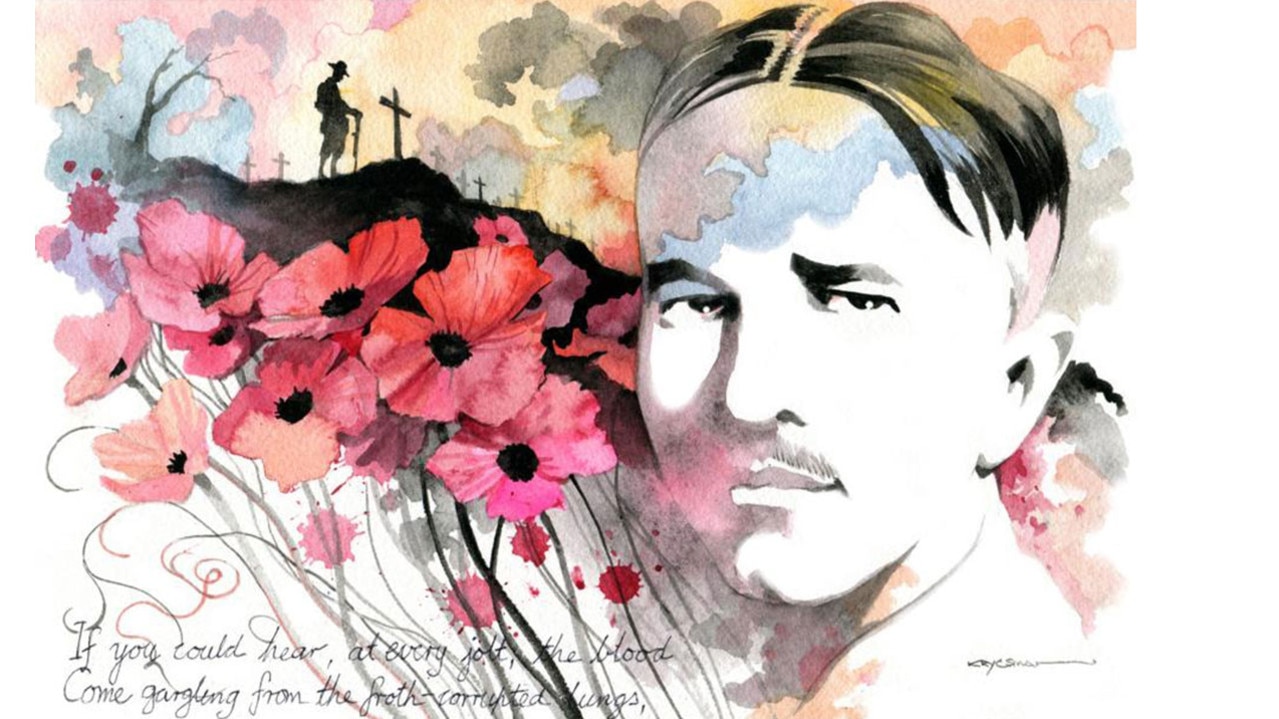

See also in In That Howling Infinite, November 1918 – the counterfeit peace and Dulce et ducorem est – the death of Wilfred Owen

Rudyard Kipling

Kipling and the Great War

© Paul Hemphill 2022. All rights reserved

Christopher Hitchens, Vanity Fair, February 1997

Recently, amid the legions of anonymous W.W.I grave sites that cover northern France, the body of Rudyard Kipling’s son, John, was identified, almost 80 years after he died in the Battle of Loos. His tragic story explains the guilt and rage that consumed his father, England’s immortal Bard of Empire

Fin de Siècle

In Regeneration, the opening book of Pat Barker’s “Ghost Road” trilogy, about the First World War, one of the characters summons the waking nightmare of the trenches: “I was going up with the rations one night and I saw the limbers against the skyline, and the flares going up. What you see every night. Only I seemed to be seeing it from the future. A hundred years from now they’ll still be ploughing up skulls. And I seemed to be in that time and looking back. I think I saw our ghosts.”

A ghost is something that is dead but won’t lie down. Those who were slaughtered between 1914 and 1918 are still in our midst to an astonishing degree. On the first day of the Battle of the Somme, in July 1916, the British alone posted more killed and wounded than appear on the whole of the Vietnam memorial. In the Battle of Verdun, which began the preceding February, 675,000 lives were lost. Between them, Britain, France, the United States, Germany, Turkey, and Russia sacrificed at least 10 million soldiers. And this is to say nothing of civilian losses. Out of the resulting chaos and misery came the avenging forces of Fascism and Stalinism.

One reason for the enduring and persistent influence of the Great War (as they had to call it at the time, not knowing that it would lead to a second and even worse one) is that it shaped the literature of the Anglo-American world. Think of the titles that remain on the shelves: Good-Bye to All That, by Robert Graves, Anthem for Doomed Youth, by Wilfred Owen. The poetry of Rupert Brooke and Siegfried Sassoon. Translations from German and French, such as Erich Maria Remarque’s All Quiet on the Western Front and Under Fire, by Henri Barbusse. By enlisting in the Great War, a whole generation of Americans, including William Faulkner, Ernest Hemingway, e. e. cummings, and John Dos Passos, made the leap from small-town U.S.A. to 20th-century modernism. Loss of moral virginity and innocence is the burden of Sebastian Faulks’s elegiac novel, Birdsong, written in this decade, but as full of pain and poetry as if composed in his grandfather’s time. We owe the term “shell shock” to this period, and it sometimes feels as if the shock has never worn off.

I’ve been passing much of my time, over the past year or so, in trying to raise just one of these ghosts. On September 27, 1915, during the Battle of Loos, a young lieutenant of the Irish Guards was posted “wounded and missing.” His name was John Kipling, and he was the only son of the great Bard of Empire, Rudyard Kipling. Kipling never goes out of print, because he not only captured the spirit of imperialism and the white man’s burden but also wrote imperishable stories and poems—many of them to the boy John—about the magic and lore of childhood. And on that shell-shocked September day, the creator of Mowgli and Kim had to face the fact that he had sacrificed one of his great loves—his son, whom he called his “man-child”—to another of his great loves: the British Empire. You can trace the influence of this tragedy through almost every line that he subsequently wrote.

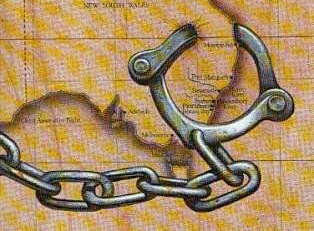

Go to the small towns of northern France today if you want to discover that the words “haunted landscape” are no cliche. Around the city of Arras, scattered along any road that you may take, are cemeteries. Kipling called them “silent cities.” (I came across an article in a French tourist magazine that recommended Arras to those who wished to pursue “de tourisme de necropole”—mass-grave tourism. Indeed, there isn’t much else to see.) This used to be the coal-bearing region of France, and great slag heaps and abandoned mine works add an additional layer of melancholy to the scenery. But otherwise it’s graveyards, graveyards all the way. Some of them are huge and orderly, with seemingly endless ranks and files of white markers stretching away in regimental patterns. But many are small and isolated, off in the middle of fields where French farmers have learned to plow around them. These represent heaps of bodies that simply couldn’t be moved and were interred where they lay. Huge land grants have been made by the government and people of France, in perpetuity, to Britain and Canada and India and the United States, just to consecrate the fallen.

His is one of the few parts of France where the locals are patient with Anglo-Saxon visitors trying to ask directions in French. And those French plowmen know what to do when, as so often happens, they turn up a mass of barbed wire or a batch of shells and mortars or a skeleton. (“A hundred years from now they’ll still be ploughing up skulls.”) They call the police, who alert the Commonwealth War Graves Commission. And then the guesswork can begin. There’s a good deal of latitude. Of the 531,000 or so British Empire dead whose remains have been fertilizing the region for most of the century, about 212,000 are still unidentified.

“Every now and then we have a bit of luck,” I was told by Peter Rolland of the commission, which runs a large and quiet office just outside Arras and which is charged with keeping all the graves clean. “Last year we dug up 12 corpses. Most of their dog tags and uniforms were eroded or decayed hopelessly. But we did manage to identify one Australian chap called Sergeant J. J. White. We even found his daughter, who was two years old when he was killed, and she came over for the funeral.”

And a few years ago, almost eight decades after he went missing, they found Kipling’s son, John. His body had lain in no-man’sland for three years and then been hastily shoveled into an unmarked grave. Kipling and his wife made several desperate visits to the area in the hope of identifying him, touring battlefield after battlefield. But this was in the days before proper dental records and DNA, and they gradually gave up. In 1992, thanks to painstaking record-keeping and the amateur interest taken by a member of the commission staff, one anonymous grave in one small cemetery was finally commemorated as John’s.

This means that a new marker has been erected. The old one read, A LIEUTENANT OF THE GREAT WAR. KNOWN UNTO GOD. The wording is actually that of Kipling Sr., who in order to atone for John’s disappearance became a founding member of what was then called the Imperial War Graves Commission, and helped design its monuments and rituals. As another atonement, he took on the unpaid job of writing the wartime history of the Irish Guards. In that work, he coldly summed up the regiment’s toll of 324 casualties in a single battle and noted that “of their officers, 2nd Lieutenant PakenhamLaw had died of wounds; 2nd Lieutenants Clifford and Kipling were missing. … It was a fair average for the day of a debut.”

John Kipling’s body had lain in no-man’s-land for three years and then been hastily shoveled into an unmarked grave.

Kipling’s autobiography, Something of Myself, is even more eerily detached. “My son John arrived on a warm August night of ’97, under what seemed every good omen.” That’s the only mention of the boy in the entire book. Kipling had already lost a beloved daughter to influenza. He seems to have felt that if he wrote any more he wouldn’t be able to trust himself.

For a father to mourn or to bury his son is an offense to the natural order of things. Yet another reason for the endless fascination of the Great War is the reverse-Oedipal fashion in which, for several lunatic years, the sight of old men burying young men was the natural order. And this in a civilized Europe bred to the expansive optimism of the late 19th century.

John Kipling was only 16 when the war broke out. Pressed, by his father to volunteer, he was rejected on the grounds of poor eyesight. (Those who have read “Baa Baa, Black Sheep,” Rudyard’s chilling story derived from his own childhood at the mercy of sadistic guardians, will remember the horror of the small boy being punished for clumsiness and poor scholarship when actually he has an undiagnosed myopia.) The proud and jingoistic father used his influence with the high command to get young John commissioned anyway. His mother’s diary recorded that “John leaves at noon. . . . He looks very straight and smart and young, as he turned [sic] at the top of the stairs to say: ‘Send my love to Dad-o.’ “

He didn’t last more than a few weeks. The village of Loos, where he disappeared, was also where the British found out about modern warfare; it was at Loos that they first tried to use poison gas as a weapon of combat. (It blew back into their own trenches, with unimaginable results.) In a neighboring sector a short while later, the British became the first to deploy a tank. But in late 1915, war was mainly blood, mud, bayonets, and high explosives.

Accounts of the boy’s last moments differ, but Kipling’s friend H. Rider Haggard (creator of King Solomon’s Mines and She) took a lot of trouble interviewing witnesses. He recorded in his diary that one of them, a man named Bowe, “saw an officer who he could swear was Mr Kipling leaving the wood on his way to the rear and trying to fasten a field dressing round his mouth which was badly shattered by a piece of shell. Bowe would have helped him but for the fact that the officer was crying with the pain of the wound and he did not want to humiliate him by offering assistance. I shall not send this on to Rudyard Kipling—it is too painful.”

Indeed it would have been: a halfblind kid making his retreat under fire and in tears, with a devastating wound. No definition of stiff upper lip would have covered it. And almost the last of John’s letters home had said, “By the way, the next time would you get me an Identification Disc as I have gone and lost mine. . . . Just an aluminum Disc with a string through it.” Probably it’s a good thing that the poet of the Raj never knew his boy died weeping. At one point he wrote, in a cynical attempt to brace himself, “My son was killed while laughing at some jest. I would I knew / What it was, and it might serve me in a time when jests are few.”

To a friend he wrote, “I don’t suppose there is much hope for my boy and the little that is left doesn’t bear thinking of. However, I hear that he finished well. . . . It was a short life. I’m sorry that all the years’ work ended in one afternoon, but lots of people are in our position, and it’s something to have bred a man.” His wife, Caroline, wrote more feelingly to her mother, “If one could but know he was dead …”

Haggard may have wished to spare Kipling pain, but one has to say that Kipling did not try to spare himself. His whole personality as an author underwent a deep change. At different stages, one can see the influence of parental anguish, of patriotic rage, of chauvinistic hatred, and of personal guilt. A single couplet almost contrives to compress all four emotions into one: “If any question why we died, / Tell them, because our fathers lied.”

These Spartan lines are anti-war and pro-war to almost the same extent. The fathers had lied, not just by encouraging their sons to take lethal risks, but by not preparing enough for war and therefore letting the young people pay for their complacency. Kipling’s longer poem “The Children” possesses the same ambiguity:

These were our children who died for our lands: they were dear in our sight.

We have only the memory left of their home-treasured sayings and laughter.

The price of our loss shall be paid to our hands, not another’s hereafter.

Neither the Alien nor Priest shall decide on it. That is our right.

But who shall return us the children?

At the hour the Barbarian chose to disclose his pretences,

And raged against Man, they engaged, on the breasts that they bared for us,

The first felon-stroke of the sword he had long-time prepared for us—

Their bodies were all our defence while we wrought our defences.

They bought us anew with their blood, forbearing to blame us,

Those hours which we had not made good when the Judgment o’ercame us.

They believed us and perished for it. Our statecraft, our learning

Delivered them bound to the Pit and alive to the burning

Whither they mirthfully hastened as jostling for honour—

Nor since her birth has our Earth seen such worth loosed upon her.

Nor was their agony brief, or once only imposed on them.

The wounded, the war-spent, the sick received no exemption:

Being cured they returned and endured and achieved our redemption,

Hopeless themselves of relief, till Death, marveling, closed on them.

That flesh we had nursed from the first in all cleanness was given

To corruption unveiled and assailed by the malice of Heaven—

By the heart-shaking jests of Decay where it lolled in the wires—

To be blanched or gay-painted by fumes— to be cindered by fires—

To be senselessly tossed and retossed in stale mutilation

From crater to crater. For that we shall take expiation.

But who shall return us our children?

After a few lines of expressive loathing about the German foe, Kipling returns to the idea that the massacre of the innocents has an element of domestic responsibility to it:

(Chalk Pit Wood was the last place his son was seen alive.) And then, giving vent to all the ghastly rumors he and his wife had heard about what happened to bodies caught in no-man’sland, he continues:

Uncertainty was torturing Kipling here into imagining the worst and most obscene fate for his son. At other times he was more resigned and more wistful, as in the short poem “My Boy Jack” (1915):

“Have you news of my boy Jack? ”

Not this tide.

“When d’you think that he’ll come back?”

Not with this wind blowing, and this tide.

“Has any one else had word of him?”

Not this tide.

For what is sunk will hardly swim,

Not with this wind blowing, and this tide.

“Oh, dear, what comfort can I find?”

None this tide,

Nor any tide,

Except he did not shame his kind—

Not even with that wind blowing, and that tide.

Then hold your head up all the more,

This tide,

And every tide;

Because he was the son you bore,

And gave to that wind blowing and that tide!

The impression that the seeker in the poem is a woman. Odd to think of Kipling as having a feminine aspect, but perhaps the verse is meant as a tribute to his American wife, who was driven almost out of her mind with grief. On the other hand, one might throw sentiment to one side and remember that Kipling famously wrote (in a poem designed to tease a daughter who favored female suffrage) that “the female of the species is more deadly than the male.” And this is most certainly true of the main character in a subsequent short story of Kipling’s entitled “Mary Postgate.” Angus Wilson once described it as evil; at all events it is a paean of hatred and cruelty and shows Kipling banishing all his doubts and guilts in favor of one cathartic burst of sickening revenge.

Mary Postgate is a wartime spinster who looks after an elderly lady in an English village. One day, a German airman crashes in her garden and lies crippled in the laurel bushes. Mary Postgate decides to see how long it will take him to die. She tells nobody about the intruder and makes no effort to summon help. She waits and watches “while an increasing rapture laid hold on her.” As the young man finally expires, she “drew her breath short between her teeth and shivered from head to foot.” Then she takes a “luxurious hot bath before tea” and, “lying all relaxed on the other sofa,” startles her employer by looking, for once, “quite handsome!”

It’s really seriously creepy to find Kipling—normally rather reticent in such matters—writing a caricature of a female orgasm and wallowing in the voluptuousness of sadism. The justification for it all is that a child has been killed by a bomb in the village. “I have seen the dead child,” says Mary Postgate to the dying airman. So the link is unmistakable. And the story—published in 1917—is closed by one of the worst sets of verses that this splendid poet ever composed. Its refrain is the line “When the English began to hate.” Omitted from most anthologies, it is a vulgar and bullying rant, which promises that “Time shall count from the date / That the English began to hate.”

I first became aware of the poem when it was dished out as a leaflet by a British Nazi organization in the 1970s. (David Edgar makes use of it in Destiny, his incisive play about the mentality of Fascism.) I have often thought it very fortunate that Kipling died in 1936. He had already begun to praise Mussolini by then, and God knows what he might have said about the manly new Germany-even though his visceral dislike of all Germans would perhaps have kept him in check. He certainly disliked Germans (whom he habitually called “Huns”) even more than he did Jews (whom he generally called “Hebrews”).

His letters are fiercer than his poems and short stories, and like them they took a turn for the worse after John’s disappearance. To his old friend L. C. Dunsterville he wrote, at the height of the bloodletting in September 1916, that things seemed to be going jolly well on the Western Front. “It’s a scientific-cumsporting murder proposition with enough guns at last to account for the birds, and the Hun is having a very sickly time of it. He has the erroneous idea that he is being hurt, whereas he won’t know what real pain means for a long time. I almost begin to hope that when we have done with him there will be very little Hun left.”

The word for this, in or out of context, is “unseemly.”

Most interesting, though, was his extensive wartime correspondence with Theodore Roosevelt. One has to remember that Kipling at that time was the best-known living writer in the English language. His following in the United States was immense. His famous poem “The White Man’s Burden,” more often quoted than read, had actually been written for Roosevelt in 1898 and was addressed to the U.S. Congress. It urged that body (successfully) to “take up the white man’s burden” by annexing the newly conquered Philippines. Such was Kipling’s ability to sway public opinion on both sides of the Atlantic that in 1914, when the Liberal British foreign secretary, Sir Edward Grey, heard that Kipling was planning a trip to America, Grey told the Cabinet that unless he was assured that this dangerous Tory poet was going in an unofficial capacity he would resign at once.

Teddy Roosevelt, of course, favored American entry into the Great War, and Kipling made a point of supplying him with ammunition. The poet didn’t hesitate to make very emotional appeals, and as a result gave a few hostages to fortune. In December 1914 he wrote to T.R. telling him encouragingly that the Germans “have been sending up their younger men and boys lately on our front. This is valuable because these are prospective fathers, and they come up to the trenches with superb bravery. Then they are removed.”

The letter goes on, “Suppose my only son dies, I for one should not View with equanimity’ Mr Wilson (however unswayed by martial prejudice) advising or recommending my country how to behave at the end of this War.” Kipling really despised Woodrow Wilson and his hypocritical neutrality, and after John’s death he gave his contempt free rein, describing Wilson as equivalent to an ape looking down from a tree. “My grief,” he wrote, “is that the head of the country is a man unconnected by knowledge or experience with the facts of the world in which we live. All of which must be paid for in the lives of good men.”

This relentless drumbeat, which also urged T.R. in menacing tones to beware of the millions of potentially disloyal German-Americans, helped breed a prowar atmosphere in the United States. Many of the Americans who went to fight in Europe did so as volunteers, preparing the ground for later, full-scale intervention. And when the American Expeditionary Force got going, it took heavy casualties. Among these was Quentin Roosevelt, son of Teddy, who was killed while serving as a pilot. T.R.’s response was almost Kiplingesque in its gruffness. “My only regret is that I could not give myself,” he said. But of course he could not have given himself, any more than Kipling could. This was an opportunity open strictly to sons.

The creator of Mowgli and Kim sacrificed one of his great loves-his son-to another of his great loves: the British Empire.

The current tenant of Headstone Two I in Row D of Plot Seven in St. Mary’s I Advanced Dressing Station Cemetery never had any idea of what a titanic conflict had snuffed out his life. Nor had he any notion of the role his death would play in his father’s poetry or his father’s propaganda. His is just one of 1,768 British and 19 Canadian graves in St. Mary’s ADS, 1,592 of which are unidentified and likely to remain so forever.

The gardener, Ian Nelson, met me at the gate and took me around. He was a working-class type from my hometown in Hampshire, just one of the many hundreds of people who live and work in northern France, stranded in time, preserving a moment and observing the decencies. He wasn’t the garrulous type, preferring to roll his own cigarettes and to say briefly that he was “old-fashioned” and “felt we owed something” to the fallen. His main enemies were the moles, which spoil the flower beds and lawns. He explained to me how certain alpine and herbaceous plantings protect the headstones from mud splashes in the winter and mowing machines in the summer. Floribunda roses were in profusion, and baby maple trees, and there was the odd Flanders poppy.

The register and the visitors’ book were kept in a metal-and-stone safe in a corner of the cemetery, and as we got there we found an old metal button in the dirt. It was a standard-issue Great War soldier’s button, with a faded lion-and-unicorn motif, and Mr. Nelson let me keep it with a look that said, Plenty more where that came from. Most of the names in the register are printed and have been for decades, and it is reprinted every few years. But a handwritten addition had just been made, showing that John, only son of Mr. and Mrs. Rudyard Kipling of Bateman’s, Burwash, Sussex, England, had made the supreme sacrifice while serving as a lieutenant in the Irish Guards. The visitors’ book had a space for remarks, and many visitors had done their best to say something. I didn’t want to let down the side, so I put in the last few lines of Wilfred Owen’s “The Parable of the Old Man and the Young.”

Owen was killed in a futile canal crossing skirmish just a few days before the end of the war, in November 1918 (his mother got the telegram just as the church bells were pealing for victory and a general rejoicing was getting under way), but before he died he composed the most wrenching and lyrical poetry of the entire conflict. Nearly 50 years later, it furnished the libretto for Benjamin Britten’s War Requiem. In Owen’s rewriting of the story of Abraham and Isaac, the old man is about to press the knife to the throat of his firstborn:

When lo! an angel called him out of heaven, Saying, Lay not thy hand upon the lad, Neither do anything to him. Behold,

A ram, caught in a thicket by its horns; Offer the Ram of Pride instead of him.

But the old man would not so, but slew his son,

And half the seed of Europe, one by one. □

British women tending war graves, Abbeville

By Rudyard Kipling

Every one in the village knew that Helen Turrell did her duty by all her world, and by none more honourably than by her only brother’s unfortunate child. The village knew, too, that George Turrell had tried his family severely since early youth, and were not surprised to be told that, after many fresh starts given and thrown away he, an Inspector of Indian Police, had entangled himself with the daughter of a retired non-commissioned officer, and had died of a fall from a horse a few weeks before his child was born.

Mercifully, George’s father and mother were both dead, and though Helen, thirtyfive and independent, might well have washed her hands of the whole disgraceful affair, she most nobly took charge, though she was, at the time, under threat of lung trouble which had driven her to the south of France. She arranged for the passage of the child and a nurse from Bombay, met them at Marseilles, nursed the baby through an attack of infantile dysentery due the carelessness of the nurse, whom she had had to dismiss, and at last, thin and worn but triumphant, brought the boy late in the autumn, wholly restored, to her Hampshire home.

All these details were public property, for Helen was as open as the day, and held that scandals are only increased by hushing then up. She admitted that George had always been rather a black sheep, but things might have been much worse if the mother had insisted on her right to keep the boy. Luckily, it seemed that people of that class would do almost anything for money, and, as George had always turned to her in his scrapes, she felt herself justified – her friends agreed with her – in cutting the whole non-commissioned officer connection, and giving the child every advantage. A christening, by the Rector, under the name of Michael, was the first step. So far as she knew herself, she was not, she said, a child-lover, but, for all her faults, she had been very fond of George, and she pointed out that little Michael had his father’s mouth to a line; which made something to build upon.

As a matter of fact, it was the Turrell forehead, broad, low, and well-shaped, with the widely spaces eyes beneath it, that Michael had most faithfully reproduced. His mouth was somewhat better cut than the family type. But Helen, who would concede nothing good to his mother’s side, vowed he was a Turrell all over, and, there being no one to contradict, the likeness was established.

In a few years Michael took his place, as accepted as Helen had always been – fearless, philosophical, and fairly good-looking. At six, he wished to know why he could not call her ‘Mummy’, as other boys called their mothers. She explained that she was only his auntie, and that aunties were not quite the same as mummies, but that, if it gave him pleasure, he might call her ‘Mummy’ at bedtime, for a pet-name between themselves.

Michael kept his secret most loyally, but Helen, as usual, explained the fact to her friends; which when Michael heard, he raged.

“Why did you tell? Why did you tell?” came at the end of the storm.

“Because it’s always best to tell the truth”, Helen answered, her arm round him as he shook in his cot.

“All right, but when the troof’s ugly I don’t think it’s nice.”

“Don’t you, dear?”

“No, I don’t and” – she felt the small body stiffen – “now you’ve told, I won’t call you ‘Mummy’ any more – not even at bedtimes.”

“But isn’t that rather unkind?” said Helen softly.

“I don’t care! I don’t care! You have hurted me in my insides and I’ll hurt you back. I’ll hurt you as long as I live!”

“Don’t, oh, don’t talk like that, dear! You don’t know what – “

“I will! And when I’m dead I’ll hurt you worse!”

“Thank goodness, I shall be dead long before you, darling.”

“Huh! Emma says, ‘Never know your luck’.” (Michael had been talking to Helen’s elderly, flat-faces maid.) “Lots of little boys die quite soon. So’ll I. Then you’ll see!”

Helen caught her breath and moved towards the door, but the wail of ‘Mummy! Mummy!’ drew her back again, and the two wept together.

At ten years old, after two terms at a prep. school, something or somebody gave him the idea that his civil status was not quite regular. He attacked Helen on the subject, breaking down her stammered defences with the family directness.

“Don’t believe a word of it”, he said, cheerily, at the end. “People wouldn’t have talked like they did if my people had been married. But don’t you bother, Auntie. I’ve found out all about my sort in English Hist’ry and the Shakespeare bits. There was William the Conqueror to begin with, and – oh, heaps more, and they all got on first-rate. ‘Twon’t make any difference to you, by being that – will it?”

“As if anything could – ” she began.

“All right. We won’t talk about it any more if it makes you cry”. He never mentioned the thing again of his own will, but when, two years later, he skilfully managed to have measles in the holidays, as his temperature went up tot the appointed one hundred and four he muttered of nothing else, till Helen’s voice, piercing at last his delirium, reached him with assurance that nothing on earth or beyond could make any difference between them.

The terms at his public school and the wonderful Christmas, Easter, and Summer holidays followed each other, variegated and glorious as jewels on a string; and as jewels Helen treasured them. In due time Michael developed his own interests, which ran their courses and gave way to others; but his interest in Helen was constant and increasing throughout. She repaid it with all that she had of affection or could command of counsel and money; and since Michael was no fool, the War took him just before what was like to have been a most promising career.

He was to have gone up to Oxford, with a scholarship, in October. At the end of August he was on the edge of joining the first holocaust of public-school boys who threw themselves into the Line; but the captain of his O.T.C., where he had been sergeant for nearly a year, headed him off and steered him directly to a commission in a battalion so new that half of it still wore the old Army red, and the other half was breeding meningitis through living overcrowdedly in damp tents. Helen had been shocked at the idea of direct enlistment.

“But it’s in the family”, Michael laughed.

“You don’t mean to tell me that you believed that story all this time?” said Helen. (Emma, her maid, had been dead now several years.) “I gave you my word of honour – and I give it again – that – that it’s all right. It is indeed.”

“Oh, that doesn’t worry me. It never did”, he replied valiantly. “What I meant was, I should have got into the show earlier if I’d enlisted – like my grandfather.”

“Don’t talk like that! Are you afraid of its ending so soon, then?”

“No such luck. You know what K. says.”

“Yes. But my banker told me last Monday it couldn’t possibly last beyond Christmas – for financial reasons.”

“I hope he’s right, but our Colonel – and he’s a Regular – say it’s going to be a long job.”

Michael’s battalion was fortunate in that, by some chance which meant several ‘leaves’, it was used for coast-defence among shallow trenches on the Norfolk coast; thence sent north to watch the mouth of a Scotch estuary, and, lastly, held for weeks on a baseless rumour of distant service. But, the very day that Michael was to have met Helen for four whole hours at a railway-junction up the line, it was hurled out, to help make good the wastage of Loos, and he had only just time to send her a wire of farewell.

In France luck again helped the battalion. It was put down near the Salient, where it led a meritorious and unexacting life, while the Somme was being manufactured; and enjoyed the peace of the Armentières and Laventie sectors when that battle began. Finding that it had sound views on protecting its own flanks and could dig, a prudent Commander stole it out of its own Division, under pretence of helping to lay telegraphs, and used it round Ypres at large.

A month later, and just after Michael had written Helen that there was noting special doing and therefore no need to worry, a shell-splinter dropping out of a wet dawn killed him at once. The next shell uprooted and laid down over the body what had been the foundation of a barn wall, so neatly that none but an expert would have guessed that anything unpleasant had happened.

By this time the village was old in experience of war, and, English fashion, had evolved a ritual to meet it. When the postmistress handed her seven-year-old daughter the official telegram to take to Miss Turrell, she observed to the Rector’s gardener: “It’s Miss Helen’s turn now”. He replied, thinking of his own son: “Well, he’s lasted longer than some”. The child herself came to the front-door weeping aloud, because Master Michael had often given her sweets. Helen, presently, found herself pulling down the house-blinds one after one with great care, and saying earnestly to each: “Missing always means dead.” Then she took her place in the dreary procession that was impelled to go through an inevitable series of unprofitable emotions. The Rector, of course, preached hope end prophesied word, very soon, from a prison camp. Several friends, too, told her perfectly truthful tales, but always about other women, to whom, after months and months of silence, their missing had been miraculously restored. Other people urged her to communicate with infallible Secretaries of organizations who could communicate with benevolent neutrals, who could extract accurate information from the most secretive of Hun commandants. Helen did and wrote and signed everything that was suggested or put before her.

Once, on one of Michael’s leaves, he had taken her over a munition factory, where she saw the progress of a shell from blank-iron to the all but finished article. It struck her at the time that the wretched thing was never left alone for a single second; and “I’m being manufactured into a bereaved next of kin”, she told herself, as she prepared her documents.

In due course, when all the organizations had deeply or sincerely regretted their inability to trace, etc, something gave way within her and all sensations – save of thankfulness for the release – came to an end in blessed passivity. Michael had died and her world had stood still and she had been one with the full shock of that arrest. Now she was standing still and the world was going forward, but it did not concern her – in no way or relation did it touch her. She knew this by the ease with which she could slip Michael’s name into talk and incline her head to the proper angle, at the proper murmur of sympathy.

In the blessed realization of that relief, the Armistice with all its bells broke over her and passed unheeded. At the end of another year she had overcome her physical loathing of the living and returned young, so that she could take them by the hand and almost sincerely wish them well. She had no interest in any aftermath, national or personal, of the war, but, moving at an immense distance, she sat on various relief committees and held strong views – she heard herself delivering them – about the site of the proposed village War Memorial.

Then there came to her, as next of kin, an official intimation, backed by a page of a letter to her in indelible pencil, a silver identity-disc and a watch, to the effect that the body of Lieutenant Michael Turrell had been found, identified, and re-interred in Hagenzeele Third Military Cemetery – the letter of the row and the grave’s number in that row duly given.

So Helen found herself moved on to another process of the manufacture – to a world full of exultant or broken relatives, now strong in the certainty that there was an altar upon earth where they might lay their love. These soon told her, and by means of time-tables made clear, how easy it was and how little it interfered with life’s affairs to go and see one’s grave.

“So different”, as the Rector’s wife said, “if he’d been killed in Mesopotamia, or even Gallipoli.”

The agony of being waked up to some sort of second life drove Helen across the Channel, where, in a new world of abbreviated titles, she learnt that Hagenzeele Third could be comfortably reached by an afternoon train which fitted in with the morning boat, and that there was a comfortable little hotel not three kilometres from Hagenzeele itself, where one could spend quite a comfortable night and see one’s grave next morning. All this she had from a Central Authority who lived in a board and tar-paper shed on the skirts of a razed city of whirling lime-dust and blown papers.

“By the way”, said he, “you know your grave, of course?”

“Yes, thank you”, said Helen, and showed its row and number typed on Michael’s own little typewriter. The officer would have checked it, out of one of his many books; but a large Lancashire woman thrust between them and bade him tell her where she might find her son, who had been corporal in the A.S.C. His proper name, she sobbed, was Anderson, but, coming of respectable folk, he had of course enlisted under the name of Smith; and had been killed at Dickiebush, in early ‘Fifteen. She had not his number nor did she know which of his two Christian names she might have used with his alias; but her Cook’s tourist ticket expired at the end of Easter week, and if by then she could not find her child she should go mad. Whereupon she fell forward on Helen’s breast; but the officer’s wife came out quickly from a little bedroom behind the office, and the three of them lifted the woman on to the cot.

“They are often like this”, said the officer’s wife, loosening the tight bonnet-strings. “Yesterday she said he’d been killed at Hooge. Are you sure you know your grave? It makes such a difference.”

“Yes, thank you”, said Helen, and hurried out before the woman on the bed should begin to lament again.

Tea in a crowded mauve and blue striped wooden structure, with a false front, carried her still further into the nightmare. She paid her bill beside a stolid, plain-featured Englishwoman, who, hearing her inquire about the train to Hagenzeele, volunteered to come with her.

“I’m going to Hagenzeele myself”, she explained. “Not to Hagenzeele Third; mine is Sugar Factory, but they call it La Rosière now. It’s just south of Hagenzeele Three. Have you got your room at the hotel there?”

“Oh yes, thank you, I’ve wired.”

“That’s better. Sometimes the place is quite full, and at others there’s hardly a soul. But they’ve put bathrooms into the old Lion d’Or – that’s the hotel on the west side of Sugar Factory – and it draws off a lot of people, luckily.”

“It’s all new to me. This is the first time I’ve been over.”

“Indeed! This is my ninth time since the Armistice. Not on my own account. I haven’t lost anyone, thank God – but, like everyone else, I’ve lot of friends at home who have. Coming over as often as I do, I find it helps them to have someone just look at the – place and tell them about it afterwards. And one can take photos for them, too. I get quite a list of commissions to execute.” She laughed nervously and tapped her slung Kodak. “There are two or three to see at Sugar Factory this time, and plenty of others in the cemeteries all about. My system is to save them up, and arrange them, you know. And when I’ve got enough commissions for one area to make it worth while, I pop over and execute them. It does comfort people.”

“I suppose so”, Helen answered, shivering as they entered the little train.

“Of course it does. (Isn’t lucky we’ve got windows-seats?) It must do or they wouldn’t ask one to do it, would they? I’ve a list of quite twelve or fifteen commissions here” – she tapped the Kodak again – “I must sort them out tonight. Oh, I forgot to ask you. What’s yours?”

“My nephew”, said Helen. “But I was very fond of him”.

“Ah, yes! I sometimes wonder whether they know after death? What do you think?”

“Oh, I don’t – I haven’t dared to think much about that sort of thing”, said Helen, almost lifting her hands to keep her off.

“Perhaps that’s better”, the woman answered. “The sense of loss must be enough, I expect. Well I won’t worry you any more.”

Helen was grateful, but when they reached the hotel Mrs Scarsworth (they had exchanged names) insisted on dining at the same table with her, and after the meal, in the little, hideous salon full of low-voiced relatives, took Helen through her ‘commissions’ with biographies of the dead, where she happened to know them, and sketches of their next of kin. Helen endured till nearly half-past nine, ere she fled to her room.

Almost at one there was a knock at her door and Mrs Scarsworth entered; her hands, holding the dreadful list, clasped before her.

“Yes – yes – I know”, she began. “You’re sick of me, but I want to tell you something. You – you aren’t married, are you? Then perhaps you won’t… But it doesn’t matter. I’ve got to tell someone. I can’t go on any longer like this.”

“But please -” Mrs Scarsworth had backed against the shut door, and her mouth worked dryly.

“In a minute”, she said. “You – you know about these graves of mine I was telling you about downstairs, just now? They really are commissions. At least several of them are.” Here eye wandered round the room. “What extraordinary wall-papers they have in Belgium, don’t you think? … Yes. I swear they are commissions. But there’s one, d’you see, and – and he was more to me than anything else in the world. Do you understand?”

Helen nodded.

“More than anyone else. And, of course, he oughtn’t to have been. He ought to have been nothing to me. But he was. He is. That’s why I do the commissions, you see. That’s all.”

“But why do you tell me?” Helen asked desperately.

“Because I’m so tired of lying. Tired of lying – always lying – year in and year out. When I don’t tell lies I’ve got to act ’em and I’ve got to think ’em, always. You don’t know what that means. He was everything to me that he oughtn’t to have been – the real thing – the only thing that ever happened to me in all my life; and I’ve had to pretend he wasn’t. I’ve had to watch every word I said, and think out what lie I’d tell next, for years and years!”

“How many years?” Helen asked.

“Six years and four months before, and two and three-quarters after. I’ve gone to him eight times, since. Tomorrow I’ll make the ninth, and – and I can’t – I can’t go to him again with nobody in the world knowing. I want to be honest with someone before I go. Do you understand? It doesn’t matter about me. I was never truthful, even as a girl. But it isn’t worthy of him. So – so I – I had to tell you. I can’t keep it up any longer. Oh, I can’t!”

Next morning Mrs Scarsworth left early on her round of commissions, and Helen walked alone to Hagenzeele Third. The place was still in the making, and stood some five or six feet above the metalled road, which it flanked for hundreds of yards. Culverts across a deep ditch served for entrances through the unfinished boundary wall. She climbed a few woodenfaced earthen steps and then met the entire crowded level of the thing in one held breath. She did not know that Hagenzeele Third counted twenty-one thousand dead already. All she saw was a merciless sea of black crosses, bearing little strips of stamped tin at all angles across their faces. She could distinguish no order or arrangement in their mass; nothing but a waist-high wilderness as of weeds stricken dead, rushing at her. She went forward, moved to the left and the right hopelessly, wondering by what guidance she should ever come to her own. A great distance away there was a line of whiteness. It proved to be a block of some two or three hundred graves whose headstones had already been set, whose flowers were planted out, and whose new-sown grass showed green. Here she could see clear-cut letters at the ends of the rows, and, referring to her slip, realized that it was not here she must look.

A man knelt behind a line of headstones – evidently a gardener, for he was firming a young plant in the soft earth. She went towards him, her paper in her hand. He rose at her approach and without prelude or salutation asked: “Who are you looking for?”

“Lieutenant Michael Turrell – my nephew”, said Helen slowly and word for word, as she had many thousands of times in her life.

The man lifted his eyes and looked at her with infinite compassion before he turned from the fresh-sown grass toward the naked black crosses.

“Come with me”, he said, “and I will show you where your son lies.”

When Helen left the Cemetery she turned for a last look. In the distance she saw the man bending over his young plants; and she went away, supposing him to be the gardener.