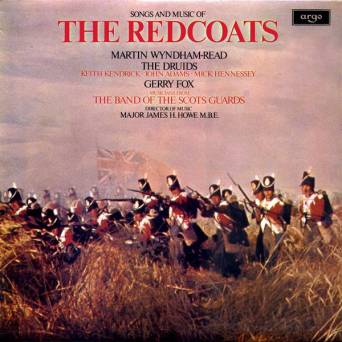

I’m not the martial type and have no temperament, time nor tolerance for militarism as a political creed, but one of my favourite folk music records is a 1970, long out of print vinyl album called Songs and Music of the Redcoats. Never re-issued on CD, it is hard to find – but English folksinger Martyn Wyndham-Read kindly sent me a copy a decade or two ago. Its sequel, The Valiant Sailor: Songs & Ballads of Nelson’s Navy, followed in 1973.

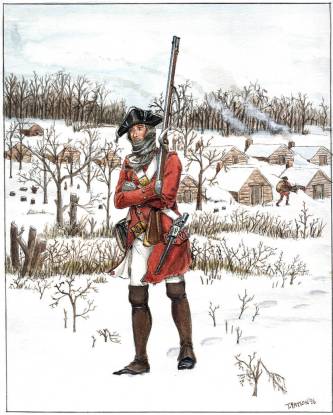

The songs range from the English Civil War to the Boer War, in which the red coat was replaced by khaki, and all the wars between. The War of the Spanish Succession, the Seven Years War (in America, the French and Indian War), the American War of Independence, the French Revolutionary War, the Crimean and Afghan Wars, the Indian Mutiny, the Sudan wars, and the South African War. Standouts for me are The Girl I Left Behind Me, which dates back to 1758, The British Soldier, with its ominous line, “we marched into Kabul and we took the Balar Hizar”, Soldiers of the Queen, which enjoyed immense popularity during the South African War, and in latter days, in the film Breaker Morant, and Stand to Your Glasses Steady, a memento mori of the prevalence of death, most often from disease, in the service of the East India Company. The featured image is from Stanley Kubrick’s 1975 film Barry Lyndon, set during the Seven Years War.

But my favourite was Over the Hills and Far Away.

Then let us list and march, I say …

This traditional English marching song has been around for four centuries, probably originating during the War of the Spanish Succession. It was published in Thomas D’Urfey’s Wit and Mirth, or Pills to Purge Melancholy in 1706 and appeared in The Recruiting Officer in 1706, a comedy by George Farquhar, and in John Gay’s The Beggar’s Opera in 1728. The lyrics refer to the War of the Spanish Succession (1701-1714), the Duke of Marlborough, and Queen Anne of England (1665 -1714).

It recalls a time when poor men joined the army out of need and the rich for glory, and when many a young man “took the king’s shilling” or bought an officer’s commission to fight in foreign wars for king or queen and country and to perish far away from home in “far away places with strange sounding names”.

So far away from home: the last stand of the 44th Foot at Gandamak during the disastrous First Afghan War of 1842.

It was very popular in Colonial and Revolutionary America, with both sides singing their own versions. The song remained popular throughout the British Empire although nowadays, its melody serving as an orchestral leitmotif in many movies, including the 1940 Hollywood classic, Northwest Passage which starred Spencer Tracy as Major Robert Rogers, leading is Rangers through French lines during the Seven Years War (1756-1763) to attack an Indian village allied to the French. But it largely faded from public consciousness, until its use in the television adaptation of Bernard Cornwell’s Sharpe series of the 1990s about the green-jacketed Rifles soldiers. I’ve heard the tune is also used in Morris dancing.

The song may have actually originated in a nursery rhyme. Tom, Tom, the Piper’s Son” mentions a piper who knows only one tune, this one, although the children’s rhyme may have itself may have started actually started its life on the stagy, written for but not included) in Thomas D’Urfey’s 1698 play The Campaigners. This is the version we sang in primary school in late fifties Birmingham:

Tom, Tom, the piper’s son,

He learnt to play when he was young,

The only tune that he could play

Was ‘over the hills and far away’;

Over the hills and a great way off,

The wind shall blow my top-knot off.

The words have changed over the years, the only consistent element in early versions being the title line and the tune. D’Urfey’s and Gay’s versions both refer to lovers, while Farquhar’s version refers to fleeing overseas to join the army, whilst Gay’s lyrics reference transportation and indentured labour in the American colonies – which is an altogether different and largely untold story.

MacHeath:

Were I laid on Greenland’s coast,

And in my arms embrac’d my lass;

Warm amidst eternal frost,

Too soon the half year’s night would pass.

And I would love you all the day.

Ev’ry night would kiss and play,

If with me you’d fondly stray

Over the hills and far away.

Polly:

Were I sold on Indian soil,

Soon as the burning day was clos’d,

I could mock the sultry toil

When on my charmer’s breast repos’d.

I would love you all the day.

Ev’ry night would kiss and play,

If with me you’d fondly stray

Over the hills and far away.

My favourite version is by English folksinger Martin Wyndham-Read. Based on Farquar’s song, it is well sung with a melodic and measured martial fife or flute accompaniments. Wyndham-Read renders it wistful, poignant, nostalgic, romantic even. It is in itself a perfect recruitment advertisement, part patriotic, part propaganda – the two often operate in unison – promising not only financial reward to folk in straightened circumstances, but camaraderie in a noble purpose, and to riff the Bard of Avon, a “happy few”, a “band of brothers”.

Hark now the drums beat up again

For all true soldier gentlemen,

Then let us list and march, I say,

Over the Hills and far away.

(Chorus)

Over the hills and o’er the main

To Flanders, Portugal and Spain,

Queen Anne commands and we’ll obey,

Over the hills and far away.

All gentlemen that have a mind,

To serve the queen that’s good and kind,

Come list and enter into pay,

Then over the hills and far away.

No more from sound of drum retreat,

While Marlborough and Galway beat

The French and Spaniards every day,

When over the hills and far away.

The song is at 5.18 on the YouTube video below. It is a recording of the full album, so indulge yourselves and listen to it in its entirety. The Sharpe version, below, is also based on Farquhar’s, acquiring new lyrics for successive episodes. It was recorded by John Tams who played Dan Hagman in the series.

If I should fall to rise no more

As many comrades did before

Then ask the fifes and drums to play

Over the Hills and Far Away

Postscript- Irish soldiers

By happenstance, as I was completing this post, I was reading The Great Hunger, published in 1962, by English historian Cecil Woodham-Smith (well known back in the day for The Reason Why, her acclaimed story of the Charge of the Light Brigade). It is, she wrote, “a curious contradiction, not very often remembered by England, that for many generations, the private soldiers of the British Army were largely Irish. The Irish have natural endowments for war, courage, daring, love of excitement and conflict; McCauley described Ireland as “an exhaustible nursery of the finest soldiers”. Poverty and lack of opportunity at home made the soldier’s shilling a day, and the chance of foreign Service, attractive to the Irishman; and the armies of which England is proud, the troops who broke the power of Napoleon in the Peninsula and defeated him at Waterloo, which fought on the scorching plains of India, stormed the heights of the Alma in the Crimean campaign, and planted the British flag in every quarter of the globe in a hundred forgotten engagements, were largely, indeed in many cases, mainly Irish”.

It has been estimated that during the American War of Independence, 16% of the rank and file in the British Army, and 31% of the commissioned officers, were Irishmen. There were indeed Irishmen fighting on both sides (Scots too, as portrayed in the final few series of that entertaining Highland fling, Outlander). In following years, the Irish would swell the ranks to the extent that by 1813 the British Army’s total manpower was estimated to be half English, a sixth Scottish and a third Irish.

For other posts about folk song in In That Howling Infinite, see: The Boys of Wexford – memory and memoir; Mo Ghile Mear in Irish myth and melody; O’Donnell Abú – the Red Earl and history in a song; Over the sea to Skye, and Outlander – if I didna hae bad luck, I’d hae no luck at all …

In addition to Songs and Music of the Redcoats and The Valiant Sailor: Songs & Ballads of Nelson’s Navy, I would also highly recommend Strawhead’s 1987 album Law Lies Bleeding (see below). My own marching song, The Marching Song of the New Republic is also included below.

© Paul Hemphill 2024. All rights reserved.