You cannot stop the birds of sadness from passing overhead, but you can sure as hell stop them nesting in your hair.

It is late summer in 1806, in the colony of New South Wales. After he loses everything he owns in a disastrous flood, former convict, failed farmer, and all-round no-hoper and ne’er-do-well Martin Sparrow heads into the wilderness that is now the Wollemi National Park in the unlikely company of an outlaw gypsy girl and a young wolfhound.

The Making of Martin Sparrow, Historian Peter Cochrane’s tale of adventure and more often than not, misadventure, is set on the middle reaches of the Hawkesbury River, north of Windsor, and the treacherous terrain of the picturesque Colo Gorge.

But first, some background history …

Between 1788 and 1868, about 162,000 convicts were transported by the British government to various penal colonies in Australia. It had began transporting convicts to the American colonies in the early 17th century, but the American Revolution had put an end to this. An alternative was required to relieve the overcrowding of British prisons and on the decommissioned warships, the hulks, that were used to house the overflow. In 1770, navigator Captain James Cook had claimed possession of the east coast of Australia for Britain, and pre-empting French designs on Terra Australis, the Great Southern Land was selected as the site of a penal colony. In 1787, the First Fleet of eleven convict ships set sail for Botany Bay, arriving on 20 January 1788 to establish the first European settlement on the continent. Botany Bay, named by Cook for its abundant and unique flora and fauna, was deemed unsuited, and six days later, the fleet hove to in the natural harbour to its north and established Sydney, named for the fleet’s commander.

Other penal colonies were later established in Tasmania – Van Diemen’s Land – in 1803 and Queensland In 1824, whilst Western Australia, founded in 1829 as a free colony, received convicts from 1850. Penal transportation to Australia peaked in the 1830s and reduced significantly in succeeding decades. The last convict ship arrived in Western Australia in 1868.

Convicts were transported primarily for petty crimes – serious crimes, like rape and murder, were punishable by death. But many were political prisoners, exiled for their participation in the Irish Rebellion of 1798 and the nascent trade union movement. Their terms served, most ex-convicts remained in Australia, and joining the free settlers, many rose to prominent positions in Australian society and commerce. Yet they and their heirs bore a social stigma – convict origins were for a long time a source of shame: “the convict stain”. Nowadays, more confident of our identity and our national story, many Australians regard a convict lineage as a cause for pride. A fifth of today’s Australians are believed to be descended from transported convicts.

A wise man doesn’t burn his bridges until he knows he can part the waters

In the young colony, for free and unfree, men and women alike, life could be nasty, brutish and short, beset by hard labour, hard living and for many, hard liquor, cursed with casual violence, and kept in order by a draconian regime of civil and military justice. Particularly so for the felons, formerly of the convict transports, and only moderately less for free settlers and the expirees, former convicts endeavouring to make a living on hard-scrabble blocks on the outer fringes of the Sydney Basin, far from young and barely civilized Sydney Town.

Cochrane’s history credentials are evident in his feel for the time and the place, the lifestyle and its accoutrements. And it’s a good pitch for a motion picture. A colonial “western” indeed, for the book echoes those fine films that portray the sordid and seedy side of the pioneer story, like Altman’s chilly McCabe and Mrs Miller, and latterly, the magnificently decadent Deadwood, with less brutal elements of Alexandra Iñárritu’s The Revenant. I noted at least two lines borrowed from classic westerns – Clint Eastwood’s avenger tale The Outlaw Josie Wales, and Arthur Penn’s frontier drama The Missouri Breaks – and there are probably more.

Cochrane has assembled a cast that is as representative and as colourful of the transplanted populace as it undoubtedly was, although some may come across to readers as a tad stereotypical and over-the-top. Loyal and honest servants of the crown like dour, Scottish Chief Constable Alister Mackie and his erudite sidekick American Thaddeus Cuff, who is never lost for bon mots and folk wisdom; whores that would not be out of place in Deadwood’s seedy Gem; cruel; corrupt soldiers who are a law unto themselves; and veterans of the Indian wars (waged by the East India Company, that is). Some are soberly righteous and others less so, given to either producing or consuming in excess a hooch named for its after effects: “bang-head”); unscrupulous and violent sealers, hunters, bushmen, and escaped convicts; and a wise and inquisitive doctor and an eccentric and obsessively peregrinating botanist intent on determining how the platypus produces its young. And, that unlikely trio at the commencement of this piece.

For many of the characters, and particularly the melancholy Martin Sparrow, it is a tale of hope and renewal, survival and redemption – again like those iconic westerns. There is something about “the frontier”, on the lawless and dangerous edges of civilization, that tries and proves a man or woman’s soul. Cuff declares that “all life turns on a pitiless wheel”, but, he adds, “we ain’t stuck in brutishness. We got a choice”.

Damnation and redemption walk hand in hand. It is perhaps no coincidence one of the river’s most righteous settlers, the former Redcoat Joe Franks, has a passion for seventeenth century Puritan preacher John Bunyan’s A Pilgrim’s Progress, that allegorical saga of faith in adversity written whilst the author was doing a twelve year stretch for his religious beliefs. Hope springs eternal on the Hobbesian frontier, and we are constantly reminded of this by the sardonic constables: “hope is the poor mans bread”, but he who lives on hope dies fasting. Whilst hope might be “the mainspring of faith, it is also “physician to misery” and “grief’s music”. And yet, to the irrepressible Romany girl, who has seen and suffered much, it might also be the “little songbird in the well of our troubled soul”.

… the search for happiness can be like the search for your spectacles when they’re sittin’ on your nose.

The country into which most of the cast venture is not, as we now acknowledge, an empty land. It was a peopled landscape, a much revered, well-loved, and worked terrain, its inhabitants possessed of deep knowledge, wisdom and respect for “country”. Cochrane acknowledges the traditional owners as they roam the fringes of his story and often venture into it, mostly as a benign presence, aiding and advising the protagonists in the mysterious ways of the wilderness.

Whilst many colonists, particularly the soldiery, regard the native peoples as savages and inflict savage reprisals upon them for their resistance to white encroachment, others, in the spirit of the contemporary ‘Enlightenment’ push back against the enveloping, genocidal tide with empathy and understanding. “It’s the first settlers do the brutal work. Them that come later, they get to sport about in polished boots and frock-coats … revel in polite conversation, deplore the folly of ill-manners, forget the past, invent some bullshit fable. Same as what happened in America. You want to see men at their worst, you follow the frontier”. “They don’t reckon we’re the Christians, Marty … We’re the Romans. We march in, seize the land, crucify them, stringing ‘em up in trees, mutilate their parts”.

But they know in their hearts that this ancient people and its ancient ways are helpless against the relentless tide of the white man’s mission civilatrice. “It might be that the bolters have the ripest imagination, but sooner or later, an official party will get across the mountains and find useful country, and the folk and the flag will follow, that’s the way of the world. It’s a creeping flood tide and there’s no ebb, and there’s no stopping it. No amount of … goodwill”. To paraphrase Henry Reynolds, acclaimed chronicler of the frontier wars, they can hear that uneasy whispering in their hearts.

Waterloo Creek Massacre, January 1838

It is Cochrane’s description of the landscape that makes an otherwise entertaining but derivative “quest” narrative soar to literally panoramic heights:

“They heard the sound of frogmouths and boobooks and night birds unknown to them, and heard the whoosh and splash and smack of fish jumping in the shallows and the constant sound of the tide chafing the banks and far off a dingo howling, and they saw the river rats scurrying for cover and myriad shapes in the dark recesses of the forest, and higher up they saw great bands of ancient sandstone, moonlit, cracked and fissured by the chisel work of ages”.

“They stood atop a cliff wall that ran north to the dense green line that marked the horizon, above a point where the valley was lost in the braided folds of mountain spurs and patches stone and a wash of the darkest forest green … The far cliffs were fractured by heavily forested gullies and slot canyons carved deep through stone. To the north he could see open patches of grassland on the valley floor, the lumpy shapes of marsupials grazing, smaller things foraging, clustered together, wood ducks and a flock of black cockatoos in full flight following the line of the far wall, the stone there fissured and scarred like the hide of a dragon”.

“Soon they were there, standing four in a line atop the stone cliffs, a sheer drop to the thickly timbered slopes that flattened to a valley floor perhaps a mile away, the river there flanked by irregular patches of forest and grass meadow and game feeding on the grasses – emu and wallaby, a wild dog loping along, and wildfowl breaking from the reeds. They saw a flock of parrots skimming the canopy, their colours coursing down like windswept rain. They saw a wedge-tailed eagle, those ragged wings, wheeling, slow, hypnotic, in the heavens above”.

Landscapes such as these are familiar to me. I view them from high places and walk the forests, and I have seen and heard the myriad birds and animals that inhabit the lands east of our Great Dividing Range. Indeed, many of them I view from my home in the forest. I felt the thrill of recognition as Cochrane’s adventurers ventured forth.

Breathtakingly beautiful it might be, but, then and now, it’s a hard and dangerous land. “… deadly cruel if you’re lost in there. I tell you both this: the wilderness in the west begs a certain reverence and demands a certain humility”.

The weather swings from searing heat to devastating floods – it is such a deluge that propels Martin Sparrow on his odyssey. The terrain in treacherous – one careless misstep and a fall can be deadly. The flora and the fauna might be exotic and magical to behold, but not everything is benign. There are snakes, funnel webs, wild dogs, eels, and bull sharks, and a particularly unpleasant wild pig. The travelers are constantly checking for mosquitoes, leeches and ticks. And the deadliest of all, the humans.

Well, these days it seems all the wilderness does is abet a multitude of crimes and occasionally a smidgen of restitution I suppose. Small mercies.

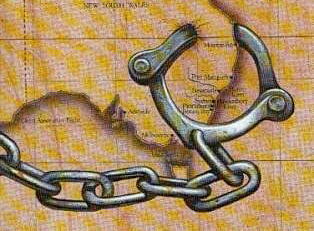

A perilous place the bush may have been, but that did not deter those who sought to venture there and indeed, find a path through the Great Dividing Range. In ensuing decades, many explorers would weave their way westwards to view that “vision splendid of the western plains extended”, as our national bard described it. But in convict days, the vision splendid was one of freedom, from slavery’s metaphorical chains -actual irons were not required in the colony because the dense and impenetrable forests that covered the lowlands and the slopes of the ranges were as “iron bars all the way to the sky” and the nomadic “savages”, de facto guards, so to speak, and for freedmen, from backbreaking toil of the their meagre farmsteads. “… it’s the misery of this mercantile tyranny … or the sovereignty of the commonweal, fire of the brutish parties that govern us here”.

Tales of an inland haven, a sanctuary from the military despotism and the rigours of pioneering were part of the convict “dreaming”. Some say this was a rhetorical ploy to throw the Law off the scent as the real escape route was by boat along the coast. The authorities dismissed it as a fantasy, a fable, or, to quote Robbie Robertson, “a drunkard’s dream if ever I did see one”. All that lay out yonder was trial and tribulation and death by a thousand stings, bites, or spears.

And yet, the magical thinking of a happy land far, far away is part of our human storytelling. “Somewhere over the rainbow, skies are blue, and the dreams that you dream of really do come true”. Even Westworld’s androids, who yearn, like Pinocchio, to be human, roam relentlessly towards the freedom of “the valley beyond”.

The notion of becoming a “bolter”is the primary theme of the story, and indeed the “making” of the luckless, lovelorn, indebted and hence perennially, melancholy Martin Sparrow who was ever wont to “stagger from one calamity to another”. A paradisaical village of free folk beyond the mountain fastness and the long arm of the constabulary, on the banks of “a river of the first magnitude” that winds its way to a mighty, whale-splashed ocean far to the west of the unknown continent, as they note, the celebrated Mr Flinders himself had surmised, their wants satisfied by bevies of copper-coloured women:

“And there it is, the most beautiful grassy woodlands that you are ever to see, and way below, a small village, embosomed in a grove of tall trees, by a most majestic river, flowing west, as far as the eye can see, and small boats gliding the channels between little islands, and women, knee-deep in the shallows, casting their nets … Olive-skinned, well-favored by nature and most pliable and yielding in all regards”.

Give a man his wish, you take away his dreams.

And so, amidst Cochrane’s historical and political exposition – and he wears his historian heart on his sleeve – and remarkable scenic descriptions, a mob of folk of widely disparate authority, status, means, temperament and ability head off in twos and threes into the wild. Some are driven by duty; for others, it’s a living; and for our unlikely duo and dog, it’s a quixotic leap in the dark. Some perish, others sicken, and several arrive at their own epiphanies and apotheoses. I recall Paul Simon: “Some have died, some have fled from themselves, or struggled from here to get there”; and also, Robert Lewis Stevenson’s observation that often, “to travel hopefully is a better thing than to arrive, and the true success is to labour”.

Till a voice, as bad as Conscience, rang interminable changes

On one everlasting Whisper day and night repeated—so:

“Something hidden. Go and find it. Go and look behind the Ranges—

“Something lost behind the Ranges. Lost and waiting for you. Go!

Rudyard Kipling, The Explorer (1898)

Orphan Girl

This beautiful song was written by Brendan Graham for the Annual Great Famine Commemoration at Sydney’s Hyde Park Barracks in 2012 to commemorate the immigration to Australia of over four thousand female orphans who, between 1848 and 1850, were brought from Ireland during the Great Hunger. It is performed by the celebrated Choral Scholars of University College of Dublin, featuring soloist Abby Molloy

For wider reading about Australian history, I highly recommend William Lines’ challenging Taming of the Great South Land’, the late Robert Hughes’ magisterial The Fatal Shore, and David Day’s Claiming a Continent. Posts in In That Howling Infinite include We got them Australia Day Blues and Outside Looking In.

As part of its marketing strategy, publisher Penguin Books, has seen fit to share extracts from the opening chapter of The Making of Martin Sparrow. I have republished them below.

1.

Sparrow woke on wet sand somewhere downriver with a terrible stink in his nostrils, the smell of death and decay, rot and ruin all about. At first he did not stir, there in the pre-dawn, pale light to the east beyond the river, the tide on the turn, ebbing now, the flow yet a faint murmur in his ears.

Confusion held him still, as did the formidable lassitude in his bones and the damp cold on his skin. The sound of his breathing confirmed the likelihood that he was alive. He raised his head and looked about, sucked up a wad of gritty phlegm and spat onto the sand. He wondered if perhaps his deliverance was the work of a kindly fate, a chance to make good his miserable existence. Hard to know.

The sand was strewn with muck and wreckage. The hen coop was there, his hens dead, in company with tangles of lumber and thatch, fence posts and scoured saplings, a big, raggedy cut of wagon canvas and a lidless coffin, the muddied panelling infested with yellow mould that glowed bright in the soft dawn light.

He sat up and brushed himself off, noticed a long cut on the inside of his forearm, but it wasn’t bad. If it was bad, deep, he might have bled to death while he lay there in the dark, half drowned. But it wasn’t and he didn’t. That was lucky.

He studied the coffin; reckoned sooner or later he’d have to take a look, in all probability stare rotting death in the face. A crow alighted on the rim, shuffled one way then the other, then hopped in, keen to join its companions. Sparrow saw a flurry of black wings as the disputatious gathering settled to its work.

There was a blood-soaked tear in his britches and a hungry leech on his thigh, like a small, fat velvet purse. He flicked the greedy little sucker onto the ground, took a twig and pierced it, watching his own blood spill out and colour the sand to russet.

In the shallows he scooped up a fragment of the Sydney Gazette, but the newspaper dissolved in his fingers as he tried to unfold the sodden sheet.

Sparrow surveyed the farms beyond the river, the flooded fields; wildfowl feeding on the flattened corn, flood-wrack washing seawards on the flow. He dropped to his knees and laved water onto the little puncture wound on his thigh and the cut on his arm. Quite why he did that he did not know for he was otherwise layered in muck all over.

Memories washed about inside his head dispelling some of the confusion – the lightning storm, the torrents of rain, the hen coop caught in the violent flow; wheat stacks coursing the river; the unremitting fury of the waters, crops awash, the bottoms gone; the exodus of reptiles; the dismal cries from distant quarters, the sound of muskets dangerously charged.

He got up and turned about, scanned the lowlands to the west, the mountains far off, full of mystery and foreboding, and full of promise too.

The sound: the ebbing tide, the pecking crows.

Sparrow stepped quietly from the water. Stood. Listened some more. He crossed the sand, took hold of the wagon sheet, heavy with wet, and edged towards the coffin until he could see the beaks spearing into that shrunken face riddled with wounds, a fledgling on the old man’s chest, pecking at his coffin suit. He did not hesitate, for their pleasure had filled him with an unfamiliar wrath and rendered him vengeful. He hurled the wagon sheet across the coffin. The captive birds panicked and leapt into the cloth and flapped and squawked and leapt again, like hearts beating in some hideous thing.

Sparrow took hold of a heavy stick and began to beat the cloth with all his might. A wing appeared askew the panelling and he smashed at it and heard the creature scream. And he kept on just so, until the canvas lay sunken in the coffin and the birds were all but still, dead or dying, their frames faintly visible. He leant on the stick, sucking for breath, awaiting further movement in the coffin, watching as blood seeped into the cloth. The birds made a few pitiful sounds, now and then a ripple or a shudder or the flap of a wing.

Sparrow stood over the coffin until the cloth stopped moving. He looked west to the mountains. Tiredness took hold. ‘Maybe it’s true, maybe I don’t got the mettle,’ he said.

He crossed the sand, stood over his coop, dropped to his knees. His hens in death, his good, sweet, giving birds, were naught but a lumpy pile of dirty feathers and claws.

He reached into the coop and gently palmed his birds apart, settling his hand upon a muddied wing; recalled the signs: the lightning storm in that inky blackness over the mountains, the discolouration of the flow and the rapid rise of the river.

But the waters had receded, briefly – a most deceptive interval that filled Sparrow with a false notion of security and he had not then seized his opportunity. He had not got in his crop, not one ear of corn; nor had he got his scarce possessions off the floor of his hut, nor moved the coop to higher ground, thus condemning the hens to a most frightful expiration, such an end as filled Sparrow with dread for reasons he did not care to contemplate. For all that, he was truly sorry.

More than once Mortimer Craggs had told him to stop being sorry. ‘Sorry for this, sorry for that,’ said Mort. ‘You got to stop being sorry, Marty, you gotta stop forthwith and seize the dream, for therein lies our path to an unfettered liberty, y’foller me?’

Sparrow did not quite follow, but he’d said yes anyway for he did not want further badgering from Mort, who was a fierce badgerer and a most indiscriminately violent man once roused. Mort might well whack a man; or he might take a filleting knife and slit his nose. You never did know what Mort might do.

Sparrow felt the sun on his back at last. Once more he looked west across the water-logged lowlands to the foothills and thence the mountains. He recalled his last conversation with Mort Craggs, before Mort took off with Shug McCafferty, before they bolted for freedom.

‘I just ain’t ready to go,’ he’d said. He was uncertain as to why Mort had invited him to join the bolt, for they were not friends, just acquaintances, a lethal acquaintance dating back to the years of his youth in the village of Blackley on the river Irk.

‘I think you don’t got the mettle, Martin,’ said Mort, fingering the ridge of proud flesh on his cropped ear.

‘I have things to say to Biddie first,’ said Sparrow.

‘Forget the whore, there’s women on the other side, there’s a big river, there’s a village, women aplenty, copper-coloured beauties, the diligence of their affections something to behold.’

‘How do you know that?’

‘Can’t say, not till you commit to the venture, swear a binding oath.’

‘I cannot swear an oath, binding or otherwise, not yet.’

The very idea of copper-coloured women on the other side of the mountains puzzled Sparrow, deeply. He was somewhat lost for a perspective on this startling infomation. ‘Like the Otahetians?’ he said.

‘No, nothin’ like them and I can say no more Marty, not another word.’

And that was the last conversation he’d had with Mort Craggs.

Sparrow had to wonder if perhaps his yearning for Biddie Happ was a foolish dream. If it was not a foolish dream before the flood it most likely was now. His thirty-acre patch was swamped, his corn crib gone, his corn crop flat in the mud, the wildfowl, the borers and the mould most likely hard at work this very day. His hut might well be gone too, lost to the flood. His hens were dead, he was deep in hock, mostly to Alister Mackie, and would have to beg for seed for another crop and that meant more hock, regardless of the weather to come. In short, it was now most unlikely that Biddie would see any chance of elevating her prospects by joining with him, Martin Sparrow, former felon, time-expired convict, failed farmer on the flood-prone bottoms of the Hawkesbury River. Fool of a man.

He sat on the sand, bowed his head and ran his fingers down his forehead, over the faint indentations that continued onto his eyelids and cheeks, the all but faded scars that folk took to be the remnants of small pox.

He tried to sort his pictorial thoughts. That wasn’t easy with Biddie presenting herself in one instant and the copper-coloured beauties in the next. ‘I should have gone with Mort,’ he said aloud. He thought about the birthmark on Biddie’s face, the mark she tried to hide with that lovely sweep of hair, pinned just so. He wondered if copper-coloured women ever got birthmarks. As to that, he just didn’t know. The mysteries, numberless.

2

Alister Mackie sipped his Hai Seng tea, treading the porch boards by the tavern door, treading to waken his bones as the pale grey light of dawn brought the distant mountains into view and the mass of huddled humanity on the village square came to life, the refugees from the flood stirring from makeshift tents on rickety frames, tattered paniers lumpy with tools and keepsakes, waifs bedded in carts and barrows, piglets trussed and tumbled in the mud, game dogs on tethers and crated fowls crooning their disquiet.

He held the mug in his two hands, sniffed at the steam coming off the brew, searching the scene: the double guard on the stone granary and the commissariat store; soldiers by the barracks door in various measures of infantry undress; washerwomen in and out of the washhouse; the butcher, busy on his scaffold, a hundred pounds of pork on the hook; the little church, the smithy, the stone gaol. The village they called Prominence.

The drudge called Fish joined Mackie on the porch. He wiped his hands on his apron. ‘You want I take the mug?’ he said.

Mackie handed him the mug.

‘They’re hammered, like castaways, every last one of them,’ said Fish.

‘They are, yes.’

‘I seen floods, but I never seen a flood like this one.’

‘Nor I.’

‘Here and there the tops of trees, otherwise an ocean.’

‘Yes.’

Mackie stepped off the porch. He weaved his way through the bivouac to the commissariat store on the far side of the square and from there he followed the ridgeline past the granary to the top of the switchback path, where he paused by the doctor’s cabin to scrutinise the work of the floodwaters below. The government garden, gone, an acre of greens torn from the slope as if scythed away by some pale rider’s mighty blade; the cottages on the terrace, squat and sodden, the weatherboard swollen and warped. Felons in the shallows, gathering up the ruins of the wharf, the guards perched on their haunches.

Mackie joined his constables, Thaddeus Cuff and Dan Sprodd, at the foot of the switchback path and together they stepped from spongy duckboards into the shallows and clambered aboard the government sloop. Packing away the mooring lines, they drifted into the current and settled at their ease. A light westerly, a port tack, the wind and the tide obliging.

Cuff patted the planking beneath the rowlock, looking up into the big gaff rig as the sail took the wind. ‘This tub reminds me of Betty Pepper,’ he said. ‘Deceptive quickness in stout disguise, charms you’d never guess first off.’

He glanced back at the cottages on the terrace and there she was, Bet, watching them go; her porch strewn with soaked possessions, the high-water mark like a dirty wainscot on the cottage wall. The young strumpet Biddie Happ was there too, squaring a muddied rug on a makeshift line. Cuff raised his hat and Bet responded with a curt swish of her hand and took a broom and set to sweeping the mud off her porch. Biddie patted at the swathe of red hair that covered the birthmark on her face.

‘They’ll miss me,’ said Cuff, ‘they cannot help themselves.’ He grabbed the wicker handles on a gallon glass demijohn, upended it, took a swig, then another, and then he passed the receptacle to Dan Sprodd.

Sprodd took a swig and passed it back to Cuff who took another swig, knowing it would aggravate the chief constable.

‘Hardly underway, you set a fine example, Thaddeus,’ said Mackie.

‘Thank you!’ said Cuff.

‘You should ration that.’ Mackie wagged a finger at him.

‘I don’t go with the shoulds, the shoulds are a tyranny. I see no joy in rationing bang-head, or anything else for that matter,’ said Cuff.

‘Americans take their liberties very seriously,’ said Sprodd, as if Mackie was sorely in need of the information.

‘Indeed, we do!’ said Cuff.

‘As do I,’ said Mackie.

‘I’ll tell you now, spirits put clout and vigour in a man. You’ll get honest toil from a pint of bang-head, miracles of effort from a quart.’

‘That or the fatal dysenteries!’

Cuff quite liked the sound of the chief ’s lowland brogue but it was too early to argue with any persistence. Sleepiness, briefly, had the better of his contrarian temperament. ‘Hear that Dan?’ he said, ‘We are not to be trusted with the drink; we, the meritorious constabulary.’