I’d rather see the world the way it used to be”

A little bit of freedom’s all we’re lack

So catch me if you can I’m goin’ back

Carole King and Gerry Goffin as sung by Dusty Springfield

Blue Remembered Hills

Into my heart an air that kills from yon far country blows:

What are those blue remembered hills,

What spires, what farms are those?

That is the land of lost content,

I see it shining plain,

The happy highways where I went

And cannot come again

From The Shropshire Lad. AE Houseman

Houseman’s famous poem looks back at childhood as a “land of lost content”; when you are a child you are innocent, and you don’t have a care in the world. He says that childhood is a “happy highway where I went and cannot come again”, implying that they are the best years of your life but that you can never go back there. When the late British playwright Dennis Potter took the poem and turned it in to a play about a group of children on their school holidays in the Forest of Dean in Gloucester, he was asking if childhood is indeed such a land of lost content and are children really so innocent.

Nostalgia, then, isn’t all it’s cracked out to be. And indeed, it can bring out the worst in us becoming a millstone of bitterness and regret strung about the necks of discontented souls who drift off into a maze of memories, meanings and emotions.

In the seventeenth century, many considered it an illness that was curable, and could be treated with opium or with trip to the countryside. Other scholars of the phenomenon have noted that until the nineteenth century it was regarded as more a geographical longing than a temporal one, homesickness for a place rather than for an era. American author and essayist Thomas Mallon wrote in a review in New Yorker: “In the same seventeenth century that prescribed methods of relief for nostalgia, writers like the poet John Milton and Robert Burton, who actually wrote a book called The Anatomy of Melancholy. went hunting for twinges of wistfulness as if these were magic mushrooms. Through the centuries, it has been regarded sometimes a harmless solace and occasionally, as a dangerous indulgence, a mental quicksand in which we allow the past to drown the present”.

Nostalgia’s pain can be exquisite, and many of those susceptible to it have sought to cultivate rather than banish the condition. But even if we do not dive in and get lost in the past, it is nevertheless built into us consciously or subliminally. We practice it culturally all of the time. It is often more triggered by the elemental senses, smell and taste and touch, than the sights and sounds from which constant revivals of fashion and music are constructed. Which, I guess, is why folk still flock to ever recycled retreads of the musicals of Andrew Lloyd Webber.

The film Casablanca has probably inspired more feelings of nostalgia than any other movie, no matter that its famous song insists that “the fundamental things apply time goes by”. Likewise Yesterday, , the most covered song in history with well over two thousand iterations: “Yesterday, my troubles seemed so far away. Now it looks as though they’re here to stay. Oh, I believe in yesterday”. As Paul sings in the “outro”, “mmm-mmm-mmm-mmm, hmm-hmm”. I reckon he played us softies like a fiddle. “Oh, it makes you wonder”, exclaims Robert Plant in Stairway to Heaven, another opaquely nostalgic piece

Comedians have been know to lampoon nostalgia. Monty Python’s famous “Four Yorkshiremen” sketch is an absurdist riff on nostalgia itself, its quartet of old codgers wallowing in pseudo-memories of deprivation and competing for pride of place with the sheer awfulness of the pasts that they invent. Australian comic Rodney Rude went outrageously further. Go google.

And then there are “memberberries”. These featured in the long running American TV show South Park in 2016 as a purple sentient grape like-fruit that rots the brain with fake nostalgia. They evoke feelings of nostalgia in those who eat them, recalling pop culture icons that engender comforting feelings for the supposedly good times of the past. They almost constantly talk about things people remember fondly, particularly the original Star Wars trilogy. They always phrase their reminiscing as “member…?” They also make conservative comments, like recalling when marriage was only between a man and Ronald Reagan. “Member when there weren’t so many Mexicans?” They appear seem to be indestructible as one was seen burned by a torch and acid, and electrified with little to no effects, but, can be squished, eaten, and shot. Their exact origin remains unknown, but they are believed to date back to Ancient Rome.

But seriously, nostalgia is like a “pathology” that presents as an inability to move forward and accept change. As technology frog-marches us into the future, we keep a constant backward glance.

Personal genealogical research, German academic and cultural historian Tobias Becker reminds us in his recent Yesterday- A New History of Nostalgia that it is the third most common use of the internet after shopping and pornography. Some of those pursuing it, he notes, are just casually curious,. Others are taking what feels like refuge in an earlier time, or seeking a more solid sense of an ethnic identity that can shape their own outlooks and politics.

And this is where it can get dangerous because the word itself can be weaponised. People on the left often insist that people overtly inclined to nostalgia are really seeking a fig leaf for their own racism. Folk of the right cleave to the revival of glory days of old, whether they existed or not, which at its most extreme can be used as a battle cry in the “war against woke”, “replacement theory” and the likes of the MAGA movement, and even Brexit.

Thomas Mallon, quoted above, provides what I consider a fair explanation for this present day fascination, and to some, preoccupation, with our past. Nostalgia, he reckons, goes much deeper than just an idea or concept. So deep in fact “that one wonders if it isn’t a neurological condition, something fundamental and immune to the vagaries of history. As people begin living beyond their Biblical allotment of seventy years, they experience the first exaggerated panics over forgetting a name or a date, which is usually remedied by a Google search. But then comes the growing realization that short-term memory has nothing like the staying power of the long-term variety. Mentally, the seven ages of man speed up their full-circling, until the past’s sovereignty over the present is complete. The further along one gets, the more one understands that the past is indeed another country, and that, moreover, it is home. Long-term memory’s domination of short may be a hardwired consolation that nature and biology have mercifully installed in us”.

Margaret Thatcher, however, often she might have invoked her hardworking grocer father, generally regarded the past as a place where she wouldn’t be caught dead (she was happier sitting atop a bulldozer or a tank).

A warm inner glow

There’s nothing inherently or intrinsically wrong with nostalgia. Nostalgia is not just wanting to go back to something that no longer exists, but wanting to go back to something because it no longer exists. It’s not just that the past is another country, to borrow JP Hartley’s famous aphorism, where they did things differently, as did we, they perceived and thought things differently too. Whilst we rejoice in “the good old days” of our youth, like the parable of the blind wise men examining an elephant, our perspective is coloured by our experiences and our circumstances before, during and after, and the expectations and assumptions, prejudices and predilections that these engendered.

When we were younger, time appeared to move more slowly than in our later years. It is in our nature to imagine and indeed, re-imagine our salad days as the best of times and the worst of times. But looking back through our back pages, these years was perhaps no better or worse, no more significant or seminal than any era fore or aft. Like objects seen through the rear-view mirror, memories always seem a lot closer and bigger. When I’ve revisited roads and streets where I grew up, playing or sauntering or rolling home with a skinful in the pale moonlight, they are no way as wide, long or spacious as they are to the mind’s eye.

Vivid memories can distort time, making you feel that that weren’t that long ago. It’s not easy to let go of what you can’t forget, particularly if your imagine yourself in a perpetual winter of discontent in which everything passes and everything changes, and the pace, the degree and the contours of change are difficult to comprehend, leaving you feeling discombobulated, disassociated and maybe, even, a little disappointed. But we do, however, enhance our depth of perception and perspective and accordingly, our understanding.

Yet, memories are fallible at the best of times, and the way we narrate our own lives can often be partial versions of the truth. Whether our images of worse-but-better times are accurate, or just scrappy patchworks of meme, myth and memory, they are deeply ingrained.

But with most things, it’s all a matter of proportion.

call it memory, call it geography, call it

the vast landscape of childhood or night—a thing

disappearing—a country turning into a map.

Stav Poleg, Memory and Geography

Sunbathing in Banalities

When we talk about the past, we always reveal something about the present. It is hard to imagine a more intriguing or overlooked body of evidence for assessing recent British social history than the Facebook groups that have proliferated in the last couple of decades as young folk have surrendered the Facebook social media space to us “boomers”. These nostalgia communities have flourished on Facebook as its user base has grown ever older in the past decade.

It may not be “representative” in any quantifiable way, but the sample size is vast, and the memes are a canvas for a whole range of contemporary insecurities and collective memories. History might be written by the winners, but anyone can share a post on Facebook. It has given us something like a more chaotic, 21st-century version of Mass Observation, that treasure trove of vox populi reportage from the ‘thirties onwards.

Though there is nothing generationally unique in the desire to bask in the banalities of our pasts, there are now many Facebook groups devoted to commemorating the same mundane aspects of life. They’re not necessarily rivals – many folk subscribe to several. British groups include The Yesteryears Revisited, Do You Remember This?, I Grew Up In The 1970s, The British Nostalgic Bible, and One Hundred and Ten Percent British. Together, these Facebook groups have close to 2 million members: more than the official pages for the Labour Party, the Conservatives and the Lib Dems combined. The baby boomer nostalgia industrial complex is thriving.

I am a member of several such groups. My favorites are Midland Memories, celebrating where I grew up in Birmingham and it’s environs; Swinging Sixties London, rejoicing in those generous times of music, colour and adventure; Yesterday’s Britain, It was a Better Britain, which is long on nostalgia and short on tolerance for “the new “, but has wonderful pictures; and three fabulous Hippie Trail groups which are a kind of virtual “school reunion” for now superannuated former rovers like myself and many friends who journeyed overland to India and beyond in the sixties and seventies.

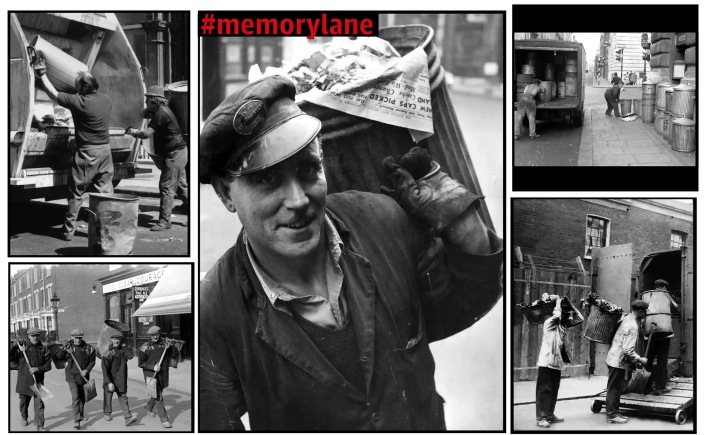

On these blue remembered hills, there are no births, marriages or deaths, no wars, no world-historic events, no great men and women of history. There is no post asking “who remembers the Cuban missile crisis?” or “who remembers the sinking of the Belgrano?” Or even, given the recent broadcasting of deliciously subversive The Crown, “where were you when you heard that Prince Di had died?” Those questions are too remote from ordinary life. Instead, we have “Who remembers ….? … bin men, street cleaners, milkmen and coal men, dinky toys and chocolate bars, gramophones, Dixon of Dock Green and Listen With Mother. We truly are … The Village Green Preservation Society:

We are the Sherlock Holmes English Speaking Vernacular

Help save Fu Manchu, Moriarty and Dracula

We are the Office Block Persecution Affinity

God save little shops, china cups and virginity

We are the Skyscraper condemnation Affiliate

God save Tudor houses, antique tables and billiards …

Preserving the old ways from being abused

Protecting the new ways for me and for you

What more can we do?

Ray Davies, The Kinks

The “proper binmen” (the featured picture of this post) and like memes are popular to a degree that may feel initially baffling. They attract phenomenal interest and enthusiasm from older Britons on Facebook, where a whole constellation of meanings and memories are projected on to them: pride, anger, resentment, weariness, ennui and fond, at times very touching, personal recollection. They embody a lost postwar idyll – and often, in many people’s imaginations, point to a decline in the fortunes of a once-proud and powerful nation and its national character, as seen in what is perceived as the apparently appalling state of their modern-day counterparts, and indeed, society as a whole, which is rotten in spirit, character and service.

The gripes of wrath

There used to be trams

Not very quick got you from place to place

But now there’s just jams, half a mile thick

Stay in the human race, I’m walking

They’ve stuck parking meters outside our door to greet us

No, Fings ain’t wot they used t’be

Monkeys flying around the moon

We’ll be up there wiv ’em soon

Fings ain’t wot they used t’be

Once our beer was froffy, but now its froffy coffee

No fings ain’t wot they used t’be

Lionel Bart, as sung by Max Bygraves

This was actually the title song of a 1959 musical produced by British playwright Joan Littlewood with songs by Lionel Bart (of Oliver fame). It launched the career of “Carry On …” star Barbara Windsor. The Carry On films, featuring the cream of contemporary British comedy, were themselves an audiovisual time capsule of a simpler time with their contrived plot lines, slapstick humour and “nudge nudge wink wink” innuendo.

It is a revelation to observe how lovely snaps of the past and “the way we were” (yet another retroflective weepy) can so easily trigger the rantings of “grumpy old white folk” against “wokey snowflakes”. The past was not better or worse than the present. It was just different and we held different views, perceptions, prejudices and, as importantly, expectations. And maybe, it is disappointed expectations and the realities of ageing that engender a jaundiced view of today’s world. To quote American baseball ace Yogi Berra, “the future ain’t what it used to be”.

Those were days when boys were boys, girls were girls, and “when chips were chips”, not microchips, and preferably with lashings of salt and vinegar and wrapped up in newspaper. These, like so much else, were much better then.

“Everyone knew their place”, lament some aging nostalgists. One member of a “memories” group shared: “In those days we had capital punishment, homosexuals were jailed, and prison was not like a holiday camp. Hardly any illegal immigrants, most children were brought up in a family with two parents who were allowed to discipline their children if necessary. The woke brigade did not exist and snowflakes only fell from the sky in the winter” Another wrote of “a lack of discipline in all walks of society, therefore lack of respect. Too many immigrants from the 50s on, not heeding Mr Powell’s wise words. Glad I’m old and won’t be here in 20 years time; I feel sorry for generations to come. Certain areas are already like the lawless, drug-fuelled, murderous parts of the Caribbean. You can never bring back those wonderful early post war times portrayed in that picture”. And another: “No wokey snowflakes, no oil protesters, no green loonies, people being allowed to get on with their lives. Happy days!” Also, while we’re at it, let’s reclaim well-loved and once casually used words like “gay”, “queer” and “fag” and many others that mean something else, usually unpleasant, today. And we never did get an answer to Spike Milligan’s Goon Show query: “What’s become of that crispy bacon we had before the war, ey?

Back in those days, we were “a gentler, kinder more law abiding and respectful society”. There was respect, you read. “Men were men and women were women. Streets were cleaner, as was our language. Policemen were politer. There were no litter, no wogs, no tattoos”. There was no intrusive and onerous health and safety regulations, so kiddies could play on the spotless streets and on unfenced and cluttered bombsites without fear of accident and stranger danger, and almost ever face you’d see was white, and you could actually see those faces

The right wing has an advantage in appealing to dislocated and atomised people: It doesn’t have to provide a compelling view of the future. All it needs is a romantic conception of the past, to which it can offer the false promise of return. When people are scared and full of despair, “let’s go back to the way things were” is a potent message, especially for those with memories of happier times. Those were invariably remembered as socially cohesive – and white.

Ever since then, to quote another song, “It’s been a hard days night …”

Many folk comment about the absence of coloured faces, hijabs, etcetera in old photos, and rant about “the invasion”. They blame “the government” for introducing mass immigration. Hardly surprising when half the government are immigrants themselves”. Some add that politicians ought to to be indigenous – whatever that means as indigeneity is a murky subject. One states that any politician should be an indigenous person . “What idiot first allowed immigrants to take office. Us ordinary folk know they don’t give a hoot for their own people they are in it for themselves and power trip and I’m talking about our own indigenous MPs as for the others …Can you imagine Brits going to Asian countries and being elected to the three highest offices in their government?it just would not happen, but here is does. this is why were are the state we are in”.

When a group member declared “time take the country back!”, I cheekily replied “where to? 1950?”

“There was a time”, someone wrote, “a time when the Sceptred Isle [that came from the Bard of Avon] was full of proper born and bred British folk … who had been through two world wars … Fought for this country … got married had two lovely white children, a boy wearing boys’ things a girl wearing girls’ things … No doubt husband still slogging away twelve hours a day down some coal pit, not sunning himself on some Caribbean island … Showed respect to king and queen … Armed forces … Police and doctors … And discipline was enforced in school and home … There was conscription and hanging and children called out “mum and and dad, auntie and uncle” … A policeman, doctor, teacher were Sir or Miss or Mrs … church on Sunday .. Christening, Confirmation, Holy Matrimony. The priest was a Vicar for the CofE … Vicar was called “Father” there were no women vicars … Catholics were tolerated but the Irish were a problem … I could go on reminiscing but it’s time for my meds and an afternoon nap … GOD SAVE THE KING and GOD SAVE THIS SEPTIC ISLE …

At this point, I realized that this stream of unconsciousness was probably a wind-up. But it encapsulated perfectly a mindset of disconsolate misery. We are not only surrounded by the ghosts of Old Britain – and here in Australia by a comparable cohort – but also by its living dead, the remnants and survivals, the attitudes and assumptions, the fallacies and fears, the nostalgia and the neurosis. As American author William Faulkner wrote, “the past is never past. It is always with us”.

Glory days

And so, the past takes on the appearance of a mythical landscape, and escapist fantasy even, of the monoculture, the civility, the cleanliness of minds, hearts, and places, the abiding sense of order, the and the idea – or the lie, more like, that if things were better run nowadays, we can retreat to it.

The following comment to an article like this one in my favourite e-zine Unherd on 3rd October 2023 put it thus: “… as my generation has aged and the future hasn’t perhaps turned out as well as our parents would have hoped, we have created a slightly cartoonish overly sentimental narrative that harks back to ‘our’ glory days. But of course, they weren’t our glory days at all – they were the glory days of our parents”.

There were never any “good old days”, really. There was poverty, slum dwellings, inequality, intolerance, deference, corporal and capital punishment. Things might seem bad today, but social, medical and technological change and growing awareness and concern for others have made life better overall. The “freedom” of those “good old days” was an illusion. Step out of line, be you female, gay or Red, long-haired or “other”, and you were taunted, cold-shouldered, black-balled or bullied. Homosexuals were jailed. “It was hard”, one member once commented, “but respectful of community. To which I replied: “…yeah, but no, but … there was always an “other”. Irish, Catholics, travelers, beatniks, teddy boys, gays, West Indians

As for everyone “knowing their place”, my place would’ve been at the bottom if not for the social and political change, including free healthcare and education, that enabled working class children to grow up healthy and ambitious.

And what’s with the discipline thing? One group member commented that the banning of corporal punishment in schools was “the start of the rot”, whatever that meant to him (yes, it’s usually males who seem dig a bit of biffo against school children – you see it often on social media when schoolies walk out on climate strikes). I never relished the ruler, cane or gym pump (which I endured, infrequently, fortunately).

Corporal punishment was often administered by teachers who enjoyed meting it out – that it was a power thing, and arguably, at times psycho-sexual. In short, child abuse. I was caned and slippered on several occasions, not for indiscipline at all but for academic performance. The teachers inflicting it were known to be bullies but the powers that be tolerated it because such measures were for “our own good” and didn’t cause long term harm. The “it made a man of me” school are possibly retrofitting their childhood experience to suit their contemporary grumpiness.

The “this will hurt me more than it hurts you”, “it’s for your own good”, and “spare the rod …” etcetera, left me cold. Nor the likes of “manners maketh the man”. I can’t say that this made a “man” of me! That, I put down to the National Health Service, free public education right through to sixth form and scholarships to university – and public libraries.

[As an aside, Fintan O’Toole’s “personal” history of modern Ireland, We don’t know ourselves, describes the horrific abuse meted out on generations of Irish children by church run schools, children’s homes and reformatories – to which the authorities turned a blind eye, and which the public tacitly condoned with its silence. O’Toole is mostly definitely in the “corporal punishment is potentially sadism or sado-masochism” camp]

When it comes to modern devices and distractions, folk hark back with a “we didn’t have … and ….” and “we had to made do with …” To which I reply “we would’ve if we could’ve if it had been invented”. Which is probably the case as we boomers took enthusiastically to music cassettes and cds, Walkman and PCs, mobile phones and smart TVs. Odds are the group members are typing their griping on an iPad or iPhone or similar.

I get it that, for some folk, there is an atavistic, rueful longing for the good old days, a golden age when things were simpler albeit less comfortable, when folk were respectful and deferential, and appreciative of the achievements and sacrifices of their fellow countrymen and, at times, women. otherwise”. But, those “seasons in the sun” were, to quote Boz, “… the worst of times and the best of times”. They were then and now is now.

Think I’m going down to the well tonight

And I’m going to drink ’til I get my fill

And I hope when I get old, I don’t sit around thinking about it

But I probably will

Yeah, just sitting back

Trying to recapture a little of the glory of

Well, the time slips away

Leaves you with nothing, mister, but boring stories of

Glory days

They’ll pass you by, glory days

In the wink of a young girl’s eye, glory days

Bruce Springsteen

A glass half full

“So what? Yes, things change. I’ve noticed. Yes”, wrote British stand-up comic, satirist, writer, and broadcaster Simon Evans, in Quillette, 2nd March 2023. “The sands of time will run through the hourglass and the desert winds will blow away the dust of my bones and raze my vainglorious monuments to the ground. Big deal. I like change. New things replace the old and the world would be boring were it not so”.

Indeed! To riff once more on Charles Dickens, the past and the present are no better or worse, just different. Times change. Things change. We change. I was born in 1949, grew up in the fifties and came of age in the sixties. “Then” was good. It is now 2023, and “now” is good too. Back “then”, I could never have imagined today.

I’m a glass half full person, and also, a keen participant on social media nostalgie. Not because I’m embittered or regretful, but rather, I derive great enjoyment from basking in “les temps perdu”. Things change, for change they must – and not all change is for the best. To some changes, I am reconciled. Others sadden me, but I have accepted that it is less than politic and also quite pointless to complain.

The “good old days” narratives that “we might’ve been poor, but we were happy” and that simpler, slower-moving times were better than today’s fast-paced, economically and socially and culturally changing world, might be comforting, but may not be realistic ones. Yes, we recall that might’ve been happier, more contented even, as Houseman might’ve thought, and our world seemed bigger and brighter, like objects seen through the rear-view mirror, as noted above; but we were young and naïve and everything was new to us. We looked about ourselves with fresh and un-taught eyes and minds. Back then, we may have been young gods and goddesses, and the open road was laid out before us.

And yet, give me today any day for all its faults, challenges and complications – and its cultural and technological advances. In truth my wife and I would not be here now if not for modern medicine. And that might well be the problem when it comes to our present “civilization and its discontents” (that’s from my old friend Nietzsche). In olden days we’d’ve been dust by now and wouldn’t have had to go through this existential “vale of tears”.

If, like dear dead Dusty, my school boy crush, who opened this piece, I’d like think that if I could go back “to the things I learned so well in my youth, those days when I was young enough to know the truth”, I’d like to take with me my twenty first century septuagenarian sense and sensibility, sans the world-weary cynicism and physical inconveniences of my age and aging – and my iPad. Forget the phone!

And every day can be my magic carpet ride

On a personal note, back in those dear gone days, I was a Roman Catholic and my folks were paddies and went to a school that was secular with a very strong CofE ethos. Boy Scout, Senior Scout. Working class, obedient to a degree but never deferential to the powers that be, republican from an early age, socialist when I reached the age of independence, though with half-informed thinking, got into fabulous music, went to uni, had sex, did drugs, hitchhiked, travelled the hippy trail, dodged the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune, and even worked for the MoD, emigrated to Australia, where, through hard yakka and a shitload of good fortune, I did quite well for myself. So I’ll admit that my up-beat perspective of today is to a very large degree due to my good fortune. Not that I’ve been especially astute, canny, and opportunistic, but rather, I’ve been lucky with the hands that have been dealt me throughout my life.

And that went right back to the beginning. As I have written often before, my brothers and I grew up in a a comfortable, happy home with loving parents and a great aunt, “with free medical treatment for all our ailments, and free optical and dental care. I still have crooked teeth – no fancy orthodontics on the NHS – but I have all my teeth still. And my eyesight. We were educated, for free. This came in during the war with the Butler Act. So, thanks to the Welfare State, we were housed and healthy enough to get to primary school and beyond. Once there, we had free books, free pens and paper, and compulsory sport, and doctors and nurses would turn up on a regular basis to check our vitals. When we came out the other side, we were free to make our own choices, and chart our own course through the reefs and shoals of life. And thus, we were able to reach the glorious ‘sixties ready to rock ‘n roll”.

Back in the days gone by

My memories are my greatest riches

From back in the days gone by ,,,…

Time moves on like a melody, and

I can hear those memories sing

Larkin Poe, Tears of Blue and Gold (2020)

Yes, my formative years were the sixties, and I wouldn’t have missed them for quids (not that I’d had anything to do with being born at the right time in the right place), when, if we wished, we were able to break free of the surly bonds of the past. I have written earlier:

“Cynics say that most people who remember the sixties were not there. Well, I was, and I remember it all so well. And was it as great as they say? Yes it was, to me at any rate. But in reality, the story of the ‘swinging sixties’ has grown with the telling. In the closing scene of The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, the journalist says: “This is the West, sir. When the legend becomes fact, print the legend”. And much of what has been remembered, written, and said about those years has followed that maxim.

This was indeed a decade of change and ferment. Values changed, morals changed, habits changed, clothes changed, music changed (the best music ever, many have argued). The way people looked at the world and thought about it. We often look back and remark that a supernova of creativity burst over the western world during those years, the likes of which was not seen before and has never been seen again. And nowhere more so than in decadent, decaying, depressing, old England, trapped in tradition, class, and prejudice.

And yet, this revolution road was walked by but a few. The greater proportion of the populace, young and old alike, carried on as if nothing untoward was happening. Following in their fathers’ footsteps, faithful to social and economic scripts written before their time, possessed of neither time, means, opportunity or inclination to indulge in the sensual, intellectual, artistic and political playground that was accessible to students and socialites of that generation. People were more affluent, no doubt, more comfortable in a maslovian sense, more socially mobile, better educated (a relative term, this), but overall, not overly adventurous. And truth be said, many of the social and political changes that are said to epitomize the ‘sixties, were well underway during the ‘fifties and even earlier or did not reach true fruition until the decades that followed.

But for we few, we happy few, in our own private Idahos, our little self-important backwaters of intellectual and cultural elitism, times were indeed a’changin”.

London was the “scene”, and then only the West End. The rest of the was still pretty drab and monochrome. But everywhere, clothes and music started to brighten things up.

With these metaphorical themes, so then did the threads unravel, so began a journey that is now drawing to a conclusion. These were the moments I occupied, looking out onto England, but imagining the wider world. And then, from the far side of the world, where the journey will most likely end, in the midst of an Australian forest. Here we are then, with the world literally at our fingertips, as we look out onto a world that is smaller, more knowledgeable, more prejudiced, less wise, more dangerous, more enthreatened, but as ever, beautiful, unfathomable, and magical. And at times like these, perhaps like Banjo, “I somehow fancy that I’d like to change with Clancy” as he “sees the vision splendid of the sunlit plains extended, and at night, the wondrous glory of the everlasting stars”. And hope that like the Bobster, we shall “dance beneath the diamond sky with one hand waving free, silhouetted by the sea, circled by the circus sand, with all memory and fate driven deep beneath the waves”. But let’s leave the last words to AA Milne as we bid farewell forever to The House at Pooh Corner: “wherever they go, and whatever happens to them on the way, in that enchanted place on the top of the Forest, a little boy and his Bear will always be playing”.

The beat goes on

When we reminisce about our “salad days”, they’re nothing more emotionally satisfying than the music we listened to; it is a portal to those times because there is nothing like songs and music from our past for unlocking memories. As the old crooner used to sing, those “magic moments” provided us with our very own soundtrack, a veritable code that even today, connects us to our contemporaries.

One constant nostalgist Facebook meme is the audio cassette tape. It inaugurated an era when it was possible to control one’s private soundscape, something we all take for granted now. It was cheap, portable, easy to use, and eminently shareable. It could live in the footwell of the a car or the bottom of a backpack. And was thrilling to those of us raised on vinyl. Suddenly, anyone with a cheap tape player could record music and share it. With its advent of the audio cassette, many of us took to compiling party tapes and car tapes of favourite songs to mark our passage from adolescence to adulthood, tapes that we would share with friends and also, with the objects of our young emotions and affections.

Nowadays, we have more ways to access music than at any time in history and a whole world of unfamiliar styles to explore, aided by instant access if we desire, to platforms like You Tube. And yet, there has been research to show that our willingness to explore new or unfamiliar music declines with age. It’s as if we believe, like American songwriter and musician Bob Seger: “today’s music ain’t got the same soul; like that old time rock ‘n’ roll”. There appears to be a consensus that people are highly likely to have their taste shaped by the music they first encounter in adolescence when our brains have developed to the point where we can fully process what we’re hearing, whilst the new experiences and heightened emotions of those years create strong and lasting bonds of memory based on pleasures past.

Farewell Middle Earth

I’ll leave my conclusion to American writer, artist and Druid (yes), Cerri Lee:

I suddenly realized it is a profound and overwhelming sense of loss for their world and mine that I feel as the Elves sail away from the Grey Havens. When the Elves leave, they take with them the enchantment from the land, something dies in it and I am left on the shores of Middle Earth amidst a fading beauty, as they sail on into the distance. The realization that now humans will have no restraints in their actions and will push forward the rise of mechanism, commerce on a global scale, and a discarding of anything that even looks like ‘fluffy’ thinking. My Middle Earth will never be the same again and I am constantly mourning its passing through this story. It leads me to wonder if some part of that feeling is what drove Tolkien to write his story.

As a fifty something woman I am starting to feel my age in the way I think. Occasionally I fall pray to the “In my day” ‘rose-tinted’ view of how things were ‘back in the day’. I don’t really think times were ever any better as such, no, definitely not better. But maybe the problems seemed more understandable, more bite sized and chewable. In truth they were not, but memory is a funny thing, as we all know, it can warp and change how we view the past.

I know that things on the global scale have always been complicated, difficult and a fine tightrope walk between warring factions, people in famine and glut, all striving for a peaceful coexistence. It is only the access to media coverage that bring the problems so close to home leaving me with the sense that I am standing before the Black Gates of Mordor, with the armies of the enemy massing on the other side and the Great Eye glaring down on me from his Tower.

© Paul Hemphill 2023. All rights reserved