Reviewing 2017, I am reminded of Game of Thrones‘ Mance Rayder’s valedictory: “I wish you good fortune in the wars to come”.

On the international and the domestic front, it appeared as if we were condemned to an infernal and exasperating ‘Groundhog Day’.

Last November, we welcomed Donald Trump to the White House with bated breath and gritted teeth, and his first year as POTUS did not disappoint. From race-relations to healthcare to tax reform to The Middle East, South Asia and North Korea, we view his bizarro administration with a mix of amusement and trepidation. Rhetorical questions just keep coming. Will the Donald be impeached? Are we heading for World War 3? How will declining America make itself “great again” in a multipolar world set to be dominated by Russia Redux and resurgent China. Against the advice of his security gurus, and every apparently sane and sensible government on the globe (including China and Russia, but not King Bibi of Iz), his Trumpfulness recognized Jerusalem as the capital of Jerusalem. Sure, we all know that Jerusalem is the capital of Israel – but we are not supposed to shout it out loud in case it unleashed all manner of mayhem on the easily irritated Muslim street. Hopefully, as with many of Trump’s isolationist initiatives, like climate change, trade, and Iran, less immoderate nations will take no notice and carry on regardless. The year closes in, and so does the Mueller Commission’s investigation into Russia’s meddling in the last presidential election and the Trumpistas’ connivance and complicity – yes, “complicit”, online Dictionary.com’s Word of the Year, introduced to us in her husky breathlessness by the gorgeous Scarlett Johansson in a spoof perfume ad that parodies Ivanka Trump’s merchandizing.

Britain continues to lumber towards the Brexit cliff, its unfortunate and ill-starred prime minister marked down as “dead girl walking”. Negotiations for the divorce settlement stutter on, gridlocked by the humongous cost, the fate of Europeans in Britain and Brits abroad, and the matter of the Irish border, which portends a return to “the troubles” – that quintessentially Irish term for the communal bloodletting that dominated the latter half of the last century. The May Government’s hamfistedness is such that at Year End, many pundits are saying that the public have forgotten the incompetence of Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn, and predict that against all odds, his missus could soon be measuring up for curtains in Number Ten.

Beset by devilish twins of Trump and Brexit, a European Union written-off as a dysfunctional, divided bureaucratic juggernaut, appears to have found hidden reserves of unity and purpose, playing hardball with Britain, dismissing the claims of Catalonia and Kurdistan, rebuking an isolationist America, and seeing-off resurgent extreme right-wing parties that threaten to fracture it with their nationalist and anti-immigration agendas. Yet, whilst Marine Le Pen and Gert Wilders came up short in the French and Dutch elections, and centrists Emmanuel Macron and Angela Merkel hold the moderate middle, atavistic, autocratic and proto-fascist parties have risen to prominence and influence in formerly unfree Eastern Europe, driven by fear of a non-existent flood of refugees from the Middle East and Africa (these are headed for the more pleasant economic climes of Germany, Britain and Scandinavia), and perhaps, their historically authoritarian DNA. Already confronted with the Russian ascendency in the east, and the prospects of the Ukrainian – Donetsk conflict firing up in the near future, the EU’s next big challenge is likely to be reacquainting itself with its original raisin d’etre – the European Project that sought to put an end to a century of European wars – and addressing the potential expulsion of parvenu, opportunistic member states who fail to uphold the union’s democratic values. As a hillbilly villain in that great series Justifed declaimed, “he who is not with is not with us”.

The frail, overcrowded boats still bob dangerously on Mediterranean and Aegean waters, and the hopeful of Africa and Asia die hopelessly and helplessly. Young people, from east and west Africa flee poverty, unemployment, and civil war, to wind up in Calais or in pop-up slave markets in free but failed Libya. In the Middle East the carnage continues. Da’ish might be finished on the battlefields of Iraq and Syria, with the number of civilian casualties far exceeding that of dead jihadis. But its reach has extended to the streets of Western Europe – dominating headlines and filling social media with colourful profile pictures and “I am (insert latest outrage)” slogans. Meanwhile, tens, scores, hundreds die as bombs explode in Iraq, Syria, Yemen, Egypt, Afghanistan and Pakistan, with no such outpourings of empathy – as if it’s all too much, too many, too far away.

Bad as 2017 and years prior were for this sad segment of our planet, next year will probably not be much better. The autocrats are firmly back in the saddle from anarchic Libya and repressed Egypt to Gulf monarchs and Iranian theocrats. There will be the wars of the ISIS succession as regional rivals compete with each other for dominance. Although it’s ship of state is taking in water, Saudi Arabia will continue its quixotic and perverse adventures in the Gulf and the Levant. At play in the fields of his Lord, VP Pence declared to US troops in December that victory was nigh, the Taliban and IS continue to make advances in poor, benighted Afghanistan. Meanwhile, Africa will continue to bleed, with ongoing wars across the Sahel, from West and Central Africa through to South Sudan, ethnic tensions in the fragile nations of the Rift Valley, and further unrest in newly ‘liberated’ Zimbabwe as its people realize that the military coup is yet another case what The Who called “meet the old boss, same as the new boss”.

In our Land Down Under, we endured the longest, most boring election campaign in living memory, and got more of the same: a lacklustre Tory government, and a depressingly dysfunctional and adversarial political system. Politicians of all parties, blinkered by short-termism, and devoid of vision, insist on fiddling whilst the antipodean Rome burns. All this only accentuates Australians’ disenchantment with their representatives, warps their perception of the value and values of “democracy”, and drives the frustrated, disgruntled, fearful and alienated towards the political extremes – and particularly the Right where ambitious but frustrated once, present and future Tory politicians aspire to greatness as big fishes in little ponds of omniphobia.

Conservative Christian politicians imposed upon us an expensive, unnecessary and bitterly divisive plebiscite on same-sex marriage which took forever. And yet, the non-compulsory vote produced a turnout much greater than the U.K. and US elections and the Brexit referendum, and in the end, over sixty percent of registered voters said Yes. Whilst constituencies with a high proportion of Muslims, Hindus, Christians and Chinese cleaved to the concept that marriage was only for man and women, the country, urban and rural, cities and states voted otherwise. The conservatives’ much-touted “silent majority” was not their “moral majority” after all. Our parliamentarians then insisted on dragging the whole sorry business out for a fortnight whilst they passed the legislation through both Houses of Parliament in an agonizingly ponderous pantomime of emotion, self-righteousness and grandstanding. The people might have spoken, but the pollies just had to have the last word. Thanks be to God they are all now off on their summer hols! And same-sex couples can marry in the eyes of God and the state from January 9th 2018.

Meanwhile, in our own rustic backyard, we are still “going up against chaos”, to quote Canadian songster Bruce Cockburn. For much of the year, as the last, we have been engaged in combat with the Forestry Corporation of New South Wales as it continues to lay waste to the state forest that surrounds us. As the year draws to a close, our adversary has withdrawn for the long, hot summer, but will return in 2018, and the struggle will continue – as it will throughout the state and indeed the nation as timber, coal and gas corporations, empowered by legislation, trash the common treasury with the assent of our many governments.

And finally, on a light note, a brief summary of what we were watching during the year. There were the latest seasons of Game of Thrones and The Walking Dead. The former was brilliant, and the latter left us wondering why we are still watching this tedious and messy “Lost in Zombieland”. Westworld was a delight with its fabulous locations and cinematography, a script that kept us backtracking to listen again to what was said and to keep up with its many ethical arcs and literary revenues. and a cavalcade of well cast, well-written and original characters. Westworld scored a post of its own on this blog – see below. The Hand Maid’s Tale wove a dystopian tale all the more rendered all the more harrowing by the dual reality that there are a lot of men in the world who would like to see women in servitude, and that our society has the technology to do it. To celebrate a triumphant return, our festive present to ourselves were tee-shirts proclaiming: “‘ave a merry f@#kin’ Christmas by order of the Peaky Blinders”. And on Boxing Day, Peter Capaldi bade farewell as the twelfth and second-best Doctor Who (David Tennant bears the crown), and we said hello to the first female Doctor, with a brief but chirpy Yorkshire “Aw, brilliant!” sign-on from Jodie Whittaker.

Whilst in Sydney, we made two visits to the cinema (tow more than average) to enjoy the big-screen experience of the prequel to Ridley Scott’s Alien and the long-awaited sequel to our all-time favourite film Blade Runner. Sadly, the former, Alien: Covenant, was a disappointment, incoherent and poorly written. The latter, whilst not as original, eye-catching and exhilarating as its parent, was nevertheless a cinematic masterpiece. It bombed at the box office, just like the original, but Blade Runner 2049 will doubtless become like it a cult classic.

This then was the backdrop to In That Howling Infinite’s 2017 – an electic collection covering politics, history, music, poetry, books, and dispatches from the Shire.

An abiding interest in the Middle East was reflected in several posts about Israel and Palestine, including republishing Rocky Road to Heavens Gate, a tale of Jerusalem’s famous Damascus Gate, and Castles Made of Sand, looking at the property boom taking place in the West Bank. Seeing Through the Eyes of the Other publishes a column by indomitable ninety-four year old Israeli writer and activist Uri Avnery, a reminder that the world looks different from the other side of the wire. The Hand That Signed the Paper examines the divisive legacy of the Balfour Declaration of 1917. The View From a Balcony in Jerusalem reviews journalist John Lyons’ memoir of his posting in divided Jerusalem. There is a Oh, Jerusalem, song about the Jerusalem syndrome, a pathology that inflects many of the faithful who flock to the Holy City, and also a lighter note, New Israeli Matt Adler’s affectionate tribute to Yiddish – the language that won’t go away.

Sailing to Byzantium reviews Aussie Richard Fidler’s Ghost Empire, a father and son road trip through Istanbul’s Byzantine past. Pity the nation that is full of beliefs and empty of religion juxtaposes Khalil Gibran’s iconic poem against a politically dysfunctional, potentially dystopian present, whilst Red lines and red herrings and Syria’s enduring torment features a cogent article by commentator and counterinsurgency expert David Kilcullen.

On politics generally, we couldn’t get through the year without featuring Donald Trump. In The Ricochet of Trump’s Counterrevolution, Australian commentator Paul Kelly argues that to a certain degree, Donald Trump’s rise and rise was attributable to what he and other commentators and academics describe as a backlash in the wider electorate against identity and grievance politics. Then there is the reblog of New York author Joseph Suglia’s original comparison between Donald Trump’s White House and Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar. But our particular favourite is Deep in the Heart of Texas, a review of an article in The New Yorker by Lawrence Wright. His piece is a cracker – a must-read for political junkies and all who are fascinated and frightened by the absurdities of recent US politics.

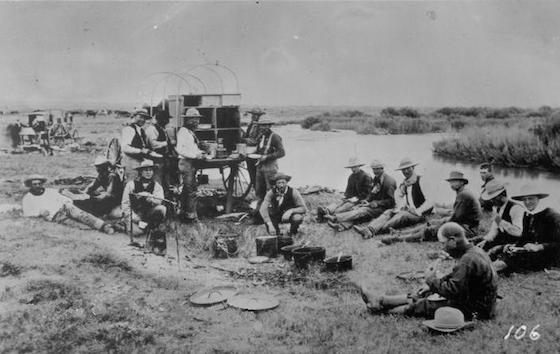

Our history posts reprised our old favourite, A Brief History of the Rise and Fall of the West, whilst we examined the nature of civil wars in A House Divided. Ottoman Redux poses a hypothetical; what if The Ottoman Empire has sided with Britain, France and Russia in World War I? In the wake of Christopher Nolan’s blockbuster movie, Deconstructing Dunkirk looked at the myths surrounding the famous evacuation. On the seventieth anniversary of the birth of India and Pakistan, we looked at this momentous first retreat from Empire with three posts: Freedom at Midnight (1) – the birth of India and Pakistan, Freedom at Midnight (2) – the legacy of partition, and Weighing the White Man’s Burden. Rewatching the excellent sci-fi drama Westworld – one of the televisual gems of 2017 – we were excited to discover how the plays of William Shakespeare were treasured in the Wild West. This inspired our last post for the year: The Bard in the Badlands – Hell is empty and the devils are here, the title referencing a line from The Tempest.

Our continuing forest fight saw us return to Tolkien’s Tarkeeth, focusing this time around on fires that recalled Robert Plant’s lyrics in Ramble On: In the darkest depths of Mordor. The trial in Coffs Harbour of the Tarkeeth Three and the acquittal of two of our activists were chronicled on a series of interviews recorded by Bellingen’s Radio 2bbb, whilst other interviews were presented in The Tarkeeth Tapes. On a lighter note, we revisited our tribute to the wildlife on our rural retreat in the bucolic The Country Life.

And finally to lighter fare. There was Laugh Out Loud – The Funniest Books Ever. Poetry offerings included the reblog of Liverpudlian Gerry Cordon’s selection of poetry on the theme of “undefeated despair”: In the dark times, will there also be singing?; a fiftieth anniversary tribute to Liverpool poets Roger McGough, Adrian Henri and Brian Patten, Recalling the Mersey Poets; and musical settings to two of our poems, the aforementioned Oh, Jerusalem, and E Lucevan Le Stelle.

And there was music. Why we’ve never stopped loving the Beatles; the mystery behind The Strange Death of Sam Cooke; Otis Redding – an unfinished life, and The Shock of the Old – the Glory Days of Prog Rock. Legends, Bibles, Plagues presented Bob Dylan’s laureate lecture. We reprised Tales of Yankee Power – how the songs of Jackson Brown and Bruce Cockburn portrayed the consequences of US intervention in Latin America during the ‘eighties. And we took an enjoyable journey into the “Celtic Twilight” with the rousing old Jacobite song Mo Ghille Mear – a piece that was an absolute pleasure to write (and, with its accompanying videos, to watch and listen to). As a Christmas treat, we reblogged English music chronicler Thom Hickey’s lovely look at the old English carol The Holly and the Ivy, And finally, for the last post of this eventful year, we selected five christmas Songs to keep the cold winter away.

Enjoy the Choral Scholars of Dublin’s University College below. and here are Those were the years that were : read our past reviews here: 2016 2015

In That Howling Infinite is now on FaceBook, as it its associate page HuldreFolk. Check them out.

And if you have ever wondered how this blog got its title, here is Why :In That Howling Infinite”?

See you in 2018.