But, as author and journalist Luke Slattery has written in a brace of articles published six years apart in The Australian, whilst The Fatal Shore says many true things about early Australia, it leaves many true things unsaid.

“Three decades after its publication”, he writes, “The Fatal Shore remains the most influential work of popular Australian history written – certainly the most widely read. Yet it is, in a very fundamental sense, wrong about early Australia. The book’s flaws have their origins in the same common source: an imagination drawn to the infernal notes of the early Australian story and insufficiently attentive to the lighter tones, the grace notes. Hughes sets out to tell a harrowing tale of systematic oppression and abuse that has been aptly described as a “gallery of horrors”. The result is a ghoulish Goya-esque aquatint rather than a rounded picture of early Australian society”.

I republish both articles below. I do not do so to gild the white settlement lily. As we now acknowledge, Australia was not an empty land. It was a peopled landscape, a much revered, well-loved, and worked terrain, its inhabitants possessed of deep knowledge, wisdom and respect for “country”. I have written passionately and often about whatI have referred to as the darkness at the heart of our history, and what many historians refer to as “the great Australian silence”. The failure of our recent referendum on an Indigenous Voive to Parliament demonstrated that as a nation, we have still to come to terms with our past. Whilst acknowledging this clearly,, Slattery’s pieces, brief as they are, tell a fascinating story of how strangers in a strange land, transplanted from half a world away, struggled, survived and over time, prospered.

But first, some background …,

Farewell to Old England forever …

Now all my young Dookies and Dutchesses

Take warning from what I’ve to say

Mind all is your own as you toucheses

Or you’ll find us in Botany Bay

Traditional folk song

Between 1788 and 1868, about 162,000 convicts were transported by the British government to various penal colonies in Australia. It had begun transporting convicts to the American colonies in the early 17th century, but the American Revolution had put an end to this. An alternative was required to relieve the overcrowding of British prisons and on the decommissioned warships, the hulks, that were used to house the overflow. In 1770, navigator Captain James Cook had claimed possession of the east coast of Australia for Britain, and pre-empting French designs on Terra Australis, the Great Southern Land was selected as the site of a penal colony.

In 1787, the First Fleet of two Royal Navy vessels, three store ships and six convict transports. On 13 May 1787 the fleet under the command of Captain Arthur Phillip, with some 1400 people, mostly convicts with an additional number of marines, sailors, civil officers and free settlers – departed Portsmouth, England on a journey of over 24,000 kilometres (15,000 miles) and over 250 days to eventually arrive in what would become the first British settlement in Australia. On 20 January 1788 the fleet made landfall at Botany Bay, named by Cook for its abundant and unique flora and fauna. Phillip deemed it unsuited due to poor soil, the lack of secure anchorage and of reliable water source. Six days later, the fleet hove to in the natural harbour to its north landing not at wha became Sydney Cove in Port Jackson (or Sydney Harbour as it is known today). On 26th January, raising the British flag and formally claiming the land for King George III. The building for the settlement began on 27th January, and on Phillip officially declared the establishment of the colony of New South Wales on 7th February 1788, becoming its first Governor.

Other penal colonies were later established in Tasmania – Van Diemen’s Land – in 1803 and Queensland In 1824, whilst Western Australia, founded in 1829 as a free colony, received convicts from 1850. Penal transportation to Australia peaked in the 1830s and reduced significantly in succeeding decades. The last convict ship, Hougoumont, left Britain in 1867 and arrived in Western Australia on 10 January 1868. In all, about 164,000 convicts were transported to the Australian colonies from Britain and Ireland between 1788 and 1868 onboard 806 ships.

Convicts were transported primarily for petty crimes – serious crimes, like rape and murder, were punishable by death. But many were political prisoners, exiled for their participation in the Irish Rebellion of 1798 and the nascent trade union movement. Their terms served, most ex-convicts remained in Australia, and joining the free settlers, many rose to prominent positions in Australian society and commerce. Yet they and their heirs bore a social stigma – convict origins were for a long time a source of shame: “the convict stain”. Nowadays, more confident of our identity and our national story, many Australians regard a convict lineage as a cause for pride. A fifth of today’s Australians are believed to be descended from transported convicts.

Almost straight away, the new colony faced starvation. The first crops failed because of the lack of skilled farmers, spoilt seed brought from England, poor local soils, an unfamiliar climate and bad tools. Phillip insisted that food be shared between convicts and free settlers. The British Officers didn’t like this, nor the fact that Phillip gave land to trustworthy convicts. But both actions meant that the colony survived

In a brief but succinct summary, Britannica describes what came next: “Increasingly, the convict element was overshadowed by men and women who came to the colony as free people. The British government encouraged migrants who, it was hoped, could employ, discipline, and perhaps reform the convicts. Few arrived until after 1815, by which time the activities of John Macarthur and other pastoralists had shown that New South Wales was well suited to the production of meat and especially wool. During the 1820s the pastoral industry attracted men of capital in large numbers. They were joined in the 1830s and ’40s by some 120,000 men, women, and children who sought to escape the harsh conditions of industrial England. Their passages were in many cases paid from a fund resulting from the decision of the British government in 1831 to sell crown land in colonies instead of giving it away. Often, they were carefully selected to remedy imbalances perceived in colonial society, such as the young women – “God’s police” – whom the philanthropist Caroline Chisholm worked to settle in pastoral districts. These migrants brought skills rather than capital and added greatly to the workforce”.

The rest, as we say, is our white history. The experience of indigenous Australians is an altogether different story: see, for example, in In That Howling Infinite, The Frontier Wars – Australia’s heart of darkness and Dark Deeds in a Sunny Land – a poet’s memorial to a forgotten crime

© Paul Hemphill 2024. All rights reserved.

Echoes

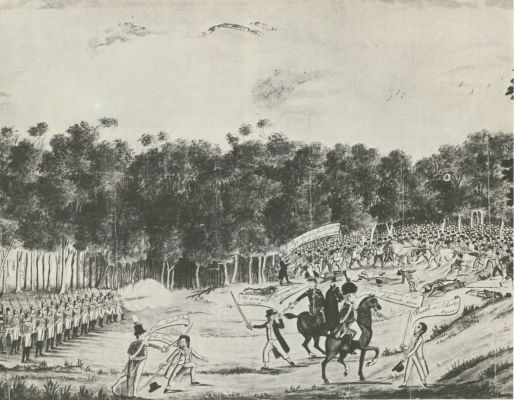

“History – and indeed, our lives – have a way of echoing across the world and down the years. In 1804, Irish convicts in the far-away penal colony of New South Wales, raised the flag of rebellion against the British soldiery and the colonial masters they served. It was the only convict rising in Australia. Many of those convicts would have been involved in the ‘98 and transported to Botany Bay for their part in it. Their quixotic Intifada was crushed at a place they called Vinegar Hill after the Wexford battle. In 1979, having migrated to Australia, I visited what is believed to be the site of the convicts’ revolt, the Castlebrook lawn cemetery on Windsor Road, Rouse Hill, where a monument commemorating the revolt was dedicated in 1988, Australia’s bicentennial year. Once open farmland, a place of market gardens and horse riding (back in the day, Adèle and I would canter across its gently rolling paddocks), it is now a suburban sprawl of McMansions”.

Extract from The Boys of Wexford – memory and memoir

It was one of life’s ironies that in London, I married an Aussie and in April 1979, immigrated Down Under. There I remained, becoming an Australian citizen and learning more and more about Australia’s history, politics and culture. See Down Under.

In Birmingham, back in the day, all I knew about Australia came from Irish folk songs like The Wild Colonial Boy and The Black Velvet Band, and The Rolf Harris Show, with the now disgraced songster painting scenes of the Australian bush on a big canvass with a broad paintbrush. It was all kangaroos, koalas and aborigines, didgeridoo and wobble board, Sun Arise and Tie Me Kangaroo Down, Sport – with winsome long-legged ladies dancing about. Everyone know the chorus of Waltzing Matilda, of course, though few know about swagmen, billabong and coolabah trees (see Banjo’s Not So Jolly Swagman – Australia’s could’ve been anthem). Then there were The Dubliners, entering the Top Ten with their rousing version of The Black Velvet Band (they also recorded the famous Pub With No Beer, about a place that just happens to be quite near where we now live in rural New South Wales – although there are other claimants). At my favourite folk club, there was a Walsall chap called Barry Roberts who sang Australian folk songs – I won a copy of his EP in the raffle – whilst touring Aussie songster, the late Trevor Lucas, gave us Fair Brisbane Ladies. Trevor went on to join Fairport Convention, marry its lead singer Sandy Denny, and later, become a founding member of The Bushwhackers, Australia’s iconic bush band.

Writing this postscript, I resolved to find out more about Barry Roberts. I discovered that he was much much than a folkie. In his daytime job as a civil liberties campaigner, legal adviser and administrator, he worked prodigiously to improve the rights of Travelers, worked on the case to exonerate the Birmingham Six convicted wrongfully of the 1974 IRA Birmingham bombings, and later, after a stint in South Australia, worked on the campaign to redress victims of Britain’s atomic tests at Maralinga. Read an excellent obituary here: https://www.theguardian.com/news/2007/aug/27/obituaries.mainsection

Further reading

For wider reading about Australian history, I highly recommend William Lines’ challenging Taming of the Great South Land’ – a history of the conquest of naturecin Australia, David Day’s Claiming a Continent, and Bruce Pascoe’s challenging Dark Emu.

In an earlier piece, The agony and extinction of Blinky Bill I wrote about Lines’ book:

“It was, and remains, an eye-opener and a page-turner. All our past, present and future environmental hotspots are covered. Squatters and selectors, rabbits and real estate, hydro and homosexuals, uranium and aluminium, environmental degradation and deforestation, and the trials of our indigenous fellow-citizens who up until a referendum in 1967 were excluded from the census – and therefore not counted [The referendum of October 14th 2023, rejecting the Indigenous Voice to Parliament and the inclusion of our First Nations in the Australian constitution, demonstrates that we have yet to come to terms with our past. [See Silencing The Voice – the Anatomy of a No voter]

Behind many of the names that are attached to our suburbs, our highways, our rivers and our mountains are the names of dead white men who were aware of, even witnessed, and were often complicit in “dark deeds in a sunny land”. Perhaps I shall write more on this at a later date, but meanwhile, the following is what Lines has to say about our iconic wildlife, and particularly, our endangered koalas”.

Lachlan Macquarie, Hyde Park, Sydney

Hughes’s Fatal Shore unfairly shows early Australia as a Gulag

Augustus Earle’s A Government Jail Gang (1830).

A year before his 50th birthday, at the height of his protean literary powers, expatriate art critic Robert Hughes published his masterpiece: a long-arc history of early colonial Australia titled The Fatal Shore. Hughes’s account, written in his engagingly virile prose, would quickly vault to bestseller status.

Three decades after its publication The Fatal Shore remains the most influential work of popular Australian history written — certainly the most widely read. Yet it is, in a very fundamental sense, wrong about early Australia.

The book’s flaws have their origins in the same common source: an imagination drawn to the infernal notes of the early Australian story and insufficiently attentive to the lighter tones, the grace notes. Hughes sets out to tell a harrowing tale of systematic oppression and abuse that has been aptly described as a “gallery of horrors”. The result is a ghoulish Goya-esque aquatint rather than a rounded picture of early Australian society.

Time magazine, to which Hughes contributed his splendid art criticism, got this right when it awarded The Fatal Shore 47th place at in its all-time top 100 nonfiction titles, describing the book as the “shocking story” of Australia’s penal colony origins: a story that submerged readers in “the dark heart of the subject matter”.

Its title, taken from a convict ballad about conditions in Tasmania soon after white settlement, has become shorthand for the early Australian reality. It has never seemed to matter that the “fatal shore” refers to the sites of secondary correction, not the mother colony at Port Jackson. The latter quickly saw itself as a way station between its origins as a penal colony and its future as a branch of civilisation.

The interesting thing about early Australia — interesting socially, politically, philosophically — was how and why it rose from a state of base felonry to democracy and prosperity. But this is not the focus of Hughes’s lengthy narrative. He’s interested in the inner circles of this antipodean hell, the lower realms of the convict system, the heart of darkness.

By the time Charles Darwin visited the colony on the Beagle in 1836, the student of natural evolution was moved to report: “On the whole, as a place of punishment the object is scarcely gained, but as a means of making men outwardly honest — of converting vagabonds, most useless in one hemisphere, into active citizens in another, and thus giving birth to a new and splendid country — a grand Centre of Civilisation — it has succeeded to a degree perhaps unparalleled in history.” Hughes records Darwin’s visit, yet he ignores this sunny manifesto of the colony’s moral significance.

Hughes framed his narrative around a powerful and lasting image of colonial Australia as a precursor to the Soviet Gulag, or concentration camp, and secondarily as a Grand Guignol, or horror story. “In Australia,” he writes, “England drew the sketch for our own century’s vaster and more terrible fresco of repression, the Gulag.” In the conclusion he again describes it as an “ancestor” of the Gulag.

Conditions at Port Jackson may have been harsh, particularly in the early years before the soils of Rose Hill (Parramatta) and the Hawkesbury began to yield maize, wheat and barley, and the colony’s sheep and cattle began to multiply. But the convicts enjoyed basic freedoms such as protection from harsh treatment under the rule of law. Their masters were not permitted to flog them. Only a court could sentence an offender to corporal punishment.

The image of the roguish convict iron gang is preserved in popular memory thanks to Augustus Earle’s watercolour of a string of malefactors at their morning muster at Hyde Park Barracks. They have threadbare hats, simian stoops, sly grins and glints in their eyes; and they regard the viewer on something like equal terms. This may have been a reality for serious offenders, reoffenders and absconders who were clapped into irons and forced to undergo hard labour. But it was manifestly not the reality for most. Most of the men, in the early years, worked unfettered in the government lumberyards, dockyards and quarries; most of the women were assigned as servants.

“Go and provide lodgings where they can be found for the remainder of the day and come to work in the morning,” the principal supervisor is reported to have told the convicts after their first muster. Before the completion of the Hyde Park Barracks most convicts were lodged in huts under the care of a convict woman. They were expected to pay for their board and washing out of money earned from overtime work.

A 20-year-old marine officer, Watkin Tench, perhaps the most appealing of the early chroniclers, describes how the fledgling colony readied itself in its first autumn for the approach of winter. Barracks were erected for the soldiers and lodgings built for married couples.

“Nor were the convicts forgotten,” he writes, “and as leisure was frequently afforded them for the purpose, little edifices quickly multiplied on the ground allotted them (on the harbour’s western edge) to build upon.” The liberality of this arrangement is astounding in the light of the Gulag metaphor.

The convict system in Tasmania was a much better fit with the Gulag image. But even then recent research of a near complete sample of Tasmanian convicts shows that they lived an average of 10 years longer than their free counterparts back in Britain.

Beyond the hours of work — dawn to 3pm in summer with Saturday afternoons and Sundays off — the convict was permitted to sell his labour, though payment was more often than not in goods or spirits. Profit-sharing schemes were not unknown. James Ruse, the first convict to be granted land by a colonial governor, induced convicts to clear his land in their own time and paid them with a share of the first crop. As skilled labour was scarce it could be sold at a high price. A man who could fix a watch could make a small fortune, even while he was serving out his term.

Before long convicts assigned to settlers on the expanding frontier were earning a set £10 a year for regular overtime, and within the first 30 years of settlement this mutated into a standard £10 annual wage. Convicts working at difficult tasks, such as construction, could earn even more in indulgences such as cuts from the settler’s table, tobacco, tea, sugar and rum.

Before their sentences had expired, usually after four years for a seven-year term, though often earlier, many were given tickets of leave: forms, in effect, of early parole. Conditional and full pardons were also used as incentives to reformation of character and necessary measures to ensure specific projects, such as the road across the Blue Mountains, were completed on time. Following a pardon, the typical emancipist was granted 30 acres (12ha) and implored to go make his fortune.

Skilled convicts such as David Dickenson Mann quickly settled into a life of bondage without any great sense of confinement. Convicted of defrauding his master in 1798, the clerk was transported for life. Arriving in Sydney in 1799, he soon found work as a clerk in the colonial bureaucracy. Less than three years later he had received an absolute pardon.

A convict such as architect Francis Greenway more or less stepped off the transport and into government employment in his former profession.

In 1819 a French ship commanded by Louis de Freycinet entered Sydney Cove. On board was Freycinet’s wife Rose and an illustrator-writer named Jacques Arago. The latter’s account of his journey, published in 1822 as Narrative of a Voyage Round the World, describes Sydney Cove in tones that seem to anticipate Darwin.

“Spacious buildings assume the place of smoky huts; an active and intelligent population is now in motion, and eager in pursuit of pleasure, on the very spot where savages formerly engaged in bloody combats,” he writes. “Obscure paths become broad and level roads: a town arises — a colony is formed — Sydney becomes a flourishing city.”

Hughes ignores this paean to the convict revolution, just as he had ignored Darwin’s.

“Some Frenchmen — though not, as a rule, those who had actually been there — did admire the English penal settlement in Australia,” he writes

As a matter of fact most French witnesses — including both Freycinets, Francois Peron in 1802 and the splendidly named Hyacinthe de Bougainville (1825) — pondered the miracle of social and moral reformation: the convict revolution.

Early in his book Hughes avers that colonial Australia was “a more normal place than one might imagine”. In his conclusion, too, he acknowledges the powerful reforming impact of the assignment system. And at various points in the book he cites evidence about the convict labour system and convict society that undermines his own broad rhetoric.

Historian John Hirst, author of Convict Society and its Enemies (1983), understood Hughes’s narrative strategy with penetrating clarity. Hughes’s acknowledgment of normality, Hirst insisted, did nothing to disturb the “controlling image of the book: that one society determined on a sort of final solution for crime by shipping its ‘scum’ to the other side of the world”.

Thirty years after its first Australian publication, The Fatal Shore still astonishes with the seductive power of its writing — its rhetoric. And in his wonderful rococo sentences, Hughes gave his all: he shows flashes of lyricism and asperity; he varies the pace of his narrative, its syntax and rhythm.

The 600-page narrative is, above all else, a masterclass in the neglected craft of writing.

He may not make of the grace notes of his narrative what the full story of convict Australian demands, but he doesn’t ignore them.

He records, for example, that the first generations of the native-born currency lads and lasses “turned out to be the most law-abiding, morally conservative people in the country. Among them, the truly durable legacy of the convict system was not ‘criminality’ but the revulsion from it: the will to be as decent as possible, to sublimate and wipe out the convict stain, even at the cost — heavily paid for in later education — of historical amnesia.”

As Hughes winds towards his ambivalent conclusion, his deep target reveals itself: the sin of sublimation, the fog of forgetting. And the book’s great triumph is that it restores the horrors of the convict system to vivid — unforgettable — life.

The Fatal Shore says many true things about early Australia, but it leaves many true things unsaid.

Luke Slattery is a Sydney-based freelance writer

A unique story with a powerful contemporary resonance

There is much to celebrate in their story. It tells how a miserable convict underclass in exile went on to build a dynamic, prosperous, open and relatively egalitarian society. This had never happened before, and it hasn’t happened since.

It’s a historical story with a powerful contemporary resonance. How do contemporary societies, both developing and developed, find ways to improve and empower citizens trapped at the lower end of the social scale? It’s an intractable dynamic that, expressed as grievance, finds expression in Trumpism, nationalism, separatism – even terrorism. But colonial Australia found answers to the problem of social advancement when a criminal class was empowered to create a society defined by the idea of advancement and liberation. It was a social and economic revolution – a revolution without a proclamation. An accidental revolution. But a revolution nevertheless.

The chief obstacle to the dissemination of this story is the usual culprit: ignorance. To take one example: many Australians – and visitors to Australia – picture colonial Sydney and Hobart as vicious prison systems. They imagine convicts incarcerated, in leg irons, flogged for petty offences, subjected to cruel and arbitrary forms of torture.

The Founding of Australia by Captain Arthur Phillip R.N. Sydney Cove, January 26th 1788

Algernon Talmage R.A First Fleet, 1787-1788

At no stage were the run-of-the-mill convicts who went ashore at Port Jackson clapped in chains: that’s part folklore, part colonial Gothic cliche, part lazy assumption.

In 1822, the British government published the detailed report of a punctilious London lawyer named John Thomas Bigge – reputedly very small – who’d been sent to investigate the state of the convict system and suggest reforms. At their first muster the newly arrived convicts were, Bigge found, “told by the principal superintendent ‘to go and provide lodging where they could for the remainder of the day, and to come to their work in the morning’.” They weren’t chained. They weren’t imprisoned. They weren’t even confined – and they didn’t shuffle around town in leg irons.

After the hours of 3pm weekdays and on Saturdays, the convicts generally worked for themselves – fixing watches, building fences or furniture – and with their earnings they were expected to pay for their “weekly lodgings and their washing”, in Bigge’s words.

[Slattery’s account of Bigge’s inquiry does not mention that he and Governor Macquarie did not get on at all, and indeed were at loggerheads over political and bureaucratic seniority – see his entry in The Australian Dictionary of Biography]

The most remarkable thing about the convict colony at the end of the earth was its air of liberality, despite the harshness of the work and the climate. Convicts were formed into various work gangs. Only hardened criminals and repeat offenders were assigned to the chain gangs.

Commissioner Bigge observed that tradesmen were generally paid “a certain weekly sum, generally amounting to 10 shillings … In return for this payment, and so long as it is regularly made, the convict is allowed to be at large at Sydney, and elsewhere, and to be at his own disposal.”

A Tory and a snob with an unshakeable disdain for the convict classes, Bigge was determined to stamp out the payment of wages drawn from His Majesty’s coffers to felons who had subverted the British property system. As the Yale historian Peter Gay wrote in his groundbreaking study of the Enlightenment, British law in these years “grew more stringent, religiously safeguarding property – or, rather, safeguarding property as if it were a new religion”.

In 1810, more than 220 offences, most of them petty, incurred the death penalty.

Convicts in government service benefited from the shortage of skilled labour in the early years. Francis Greenway, the colony’s first architect – and a convicted forger – stepped straight from his transport into permanent employment. The most common gubernatorial indulgence was the ticket-of-leave – an early form of parole that gave the convict freedom, though not freedom to leave the colony. Between 1810 and 1816, some 50 per cent of male convicts who had been sentenced to seven-year terms were paroled in this fashion after they had served three years or less.

The trouble with Robert Hughes’ Fatal Shore myth of an antipodean gulag is that it’s not only an illusion, it’s an occlusion: it obscures the very real social, moral and political value in those features of the convict system that were in part a pragmatic response to economic need. We get a very different impression from the witness accounts of visitors to, and, in one rather special case, victims of the system.

The First Fleet in Sydney Cove. Picture: National Library of Australia

In 1802, a young Frenchman named Francois Peron arrived at Sydney Harbour as part of the French “scientific” expedition commanded by Nicholas Baudin. In his journals of that voyage, Peron explicitly, though fleetingly, uses the term “revolution” to describe the mechanism of social advancement he’d witnessed first-hand at the penal colony at the end of the earth.

The mechanism of this “revolution” was, in Peron’s view, rational self-interest. The emancipated convicts were generally given land grants and starter provisions from the government stores. They were concerned with “the maintenance of order and justice, for the purposes of preserving the property they have acquired”, Peron observed.

At the same time, they “behold themselves in the situation of husbands and fathers; they have … powerful motives for becoming good members of the community in which they exist”.

Peron’s account has an English equivalent in the witness account of the 26-year-old Charles Darwin, who arrived at Sydney Cove in 1836 aboard HMS Beagle. “On the whole, as a place of punishment the object is scarcely gained, but as a means of making men outwardly honest – of converting vagabonds, most useless in one hemisphere, into active citizens in another, and thus giving birth to a new and splendid country – a grand Centre of Civilisation – it has succeeded to a degree perhaps unparalleled in history,” Darwin wrote.

It was the French who seemed the most acutely attuned to the political and moral force of the social experiment at Sydney Cove. The writer and illustrator Jacques Arago arrived in Sydney in 1819 aboard a ship commanded by Louis de Freycinet, who had smuggled his spirited wife Rose on board in the disguise of a deckhand.

Arago, too, was keen to lay bare the mechanisms of social elevation. “A convict arrives, condemned to seven years’ transportation. If he be of any trade, he may procure employment at it as soon as he arrives: and if he be industrious and frugal, he is soon enabled to work on his own account, and to earn money enough to begin a little business.”

A convict in this condition – unable to leave the colony yet free to earn wages – “is given as an assistant, or servant” in the form of a convict whose term has recently finished or “has been granted an exemption”. The servant’s labours are “recompensed; and, if he be frugal when his time has expired, he in his turn, obtains the same advantages as his master, and, like him, receives servants, who assist him in clearing fresh lands. In this manner the labour, the trouble, and the reward have been equally distributed; and while the country is improved, the man becomes better, and society is benefited.”

The Governor’s rest house at Rooty Hill in 1918. Picture: State Library of NSW

We have another early colonial narrative of personal elevation, though one that lies outside this French tradition of looking on – somewhat admiringly as Voltaire had also done – to English society from without. It’s the narrative of Joseph Mason, a convict who arrived in the colony in 1831 and returned home after an early pardon. Far from being fettered or in any sense constrained, Mason was free to roam and explore the countryside. “I have traced the (Nepean) river its whole length through the mountain both alone and with company,” he boasted.

These witness accounts of early Sydney miss much detail, some supporting their vision of a benign social revolution, some challenging it. They fail, for example, to note the tensions in the colony between ex-convict emancipists, free settlers, convicts and the military; there is only a glancing mention of the fact that many convicts spend their earnings on grog, while others return to crime. And they fail by and large to see that the sunny social experiment was made possible by an act of colonial dispossession.

Contemporary Australians, and particularly the young, tend to view the early settlement solely through the prism of colonisation and dispossession. Many others have absorbed the gulag myth propagated by Hughes, who wilfully confused the harshness of the places of secondary punishment – such as Port Arthur, Norfolk Island and Moreton Bay – with conditions and practices in the main settlements.

The untold story of the Australian revolution carries its freight – moral, political, philosophical – into our century. It suggests that individuals, and entire societies, can be improved by improving their conditions; that work and purpose are, in fact, morally uplifting.

It illuminates some of the causes of social misery, as well as some of the cures. It’s an optimistic, and a badly needed, tale.

Peron, Arago and de Bougainville were convinced they’d witnessed something worthy of philosophical reflection. Their compatriot Jules (20,000 Leagues Beneath the Sea) Verne would later embellish Peron’s account in a non-fiction mash-up of famous maritime voyages. “A more worthy subject for the reflection of a philosopher or statesman never existed – no brighter example of the influence of social institutions can be imagined – than that afforded on the distant shores of which we are speaking,” wrote Verne.

But philosophers and statesmen were a little short on the ground at Sydney Cove.

This cheering vision of what has often been seen as an infernal colony, shouldn’t skew towards utopianism. In its broad outlines the convict experience was, as Darwin put it, about remaking, conversion and elevation. But it was, nevertheless, at heart, a form of extreme punishment for mostly petty offences. For many coveys the pursuit of freedom, despite the considerable risks, was preferable to the rigidities of indentured servitude. They escaped – even from the strictly supervised chain gangs – into the bush. Many perished there.

The reason, I think, that French observers were keen to stress the philosophical implications of the Australian revolution – the wonderfully named Hyacinthe de Bougainville also makes this point during his visit of 1825 – is that the French Revolution had been so heavily freighted with unrealised, or betrayed idealism. They were attuned to the sentiments of equality and fraternity. But they had lived through bloodshed, repression and, at the end of it all, the heady swell of Bonapartism and the restoration of a repressive monarchy. What they observed at Sydney Cove was the realisation of humane social ideas without any espousal of those ideals: a revolution without a Robespierre; a revolution without a guillotine.

It was not, of course, a revolution without bloodshed. Or violence, in the form of dispossession. Or murder, on both sides. But it would be facile to reduce the one story – the celebratory story with a powerful contemporary resonance – to the other. To reduce everything to black and white. Sophisticated cultures deal with complex origin stories of many strands.

Luke Slattery is the author of four works of non-fiction and one of fiction

[…] Farewell to Old England forever … reappraising The Fatal Shore […]