In 1929, there is violence at the Western Wall in Jerusalem – then a narrow alley named for Buraq, the steed with a human face that bore the Prophet Mohammed on his midnight journey to Jerusalem, and not the Kotel Plaza of today. The event, which was actually called the Buraq rising was incited by rumours that Jews planned to overrun the Haram al Sharif, the third holiest site in Islam. A massacre of Jews in Hebron in the south followed. These were a bleak precursor of the wars to come.

Fast forward to mid-April 1936. Following two incidents of killing carried out in by both Arabs and Jews, an Arab National Committee declared a strike in the city of Jaffa. National Committees were formed in other Palestinian cities and representatives of Arab parties formed the “Arab Higher Committee” led by Haj Amin al-Husseini. A general strike spread throughout Palestine, accompanied by the formation of Palestinian armed groups that started attacking British forces and Jewish settlements. Thus began the “Great Palestinian Revolt. It lasted for three years.

Roots and fruits

The ongoing struggle with regard to the existence Israel and Palestine is justifiably regarded the most intractable conflict of modern times. Whilst most agree that its origins lie in the political and historical claims of two people, the Jewish Israelis and the predominantly Muslim Palestinians for control over a tiny wedge of one-time Ottoman territory between Lebanon and Syria in the north, Jordan in the east, and Egypt to the south, hemmed in by the Mediterranean Sea. There is less consensus as to when the Middle East Conflict as it has become known because of its longevity and its impact on its neighbours and the world in general, actually began.

Was it the infamous Balfour Declaration of 1917 promising a national home for Jews in an Ottoman governate already populated by Arabs, or the secretive Sykes Picot Agreement that preceded it in 1916, staking imperial Britain’ and France’s claim to political and economic influence (and oil pipelines) in the Levant? Was it the establishment of the British Mandate of Palestine after the Treaty of Sèvres of 1922 which determined the dissolution of the defeated Ottoman Empire. Or was it the end of that British mandate and the unilateral declaration of Israeli independence in 1948 and the war that immediately followed?

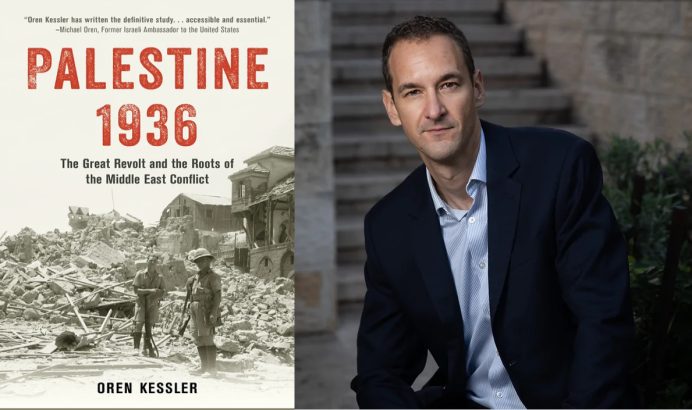

In his book Palestine 1936: The Great Revolt and the Roots of the Middle East Conflict (Rowman & Littlefield, 2023) Israeli journalist and author Oren Kessler argues powerfully that the events in Mandatory Palestine between 1936 and 1939 shaped the subsequent history of the conflict for Israelis and Palestinians. The book identifies what was known at the time as The Great Revolt as the first Intifada, a popular uprising which actually sowed the seeds of the Arab military defeat of 1947-48 and the dispossession and displacement of over seven hundred thousand Palestinian Arabs, which has set the tone of the conflict for almost a century.

It is a tragic history shared with knowledge in hindsight of the decades of violence and bloodshed in the region that followed. It begins in the time before Palestine became political entity, when mainly Eastern European Jews began settling in progressively larger numbers to the consternation of the Arab populace.

The 1936 conflict stemmed from questions of how to divide the land and how to deal with the influx of Jewish people – questions that remain relevant today. In an extensive interview coinciding with the book’s publication (republished below) Kessler notes that, for the Arab residents, the problem was one of immigration and economics; for the Zionists, it was about finding a home. These two positions soon became irreconcilable issues, leading to sporadic violence and then to continual confrontation.

He believes that the Revolt is the point when both sides really came to see the conflict as zero sum. insofar that whichever community had the demographic majority in Palestine would be the one that would determine its fate. However, in the 1920s, the Jews were so far from that majority that both sides were able to postpone the final reckoning. In the 1930s, the Jews threatened to become a majority, and this was the immediate precursor to the rising. There was no way that the objective of bringing as many Jews to the land as possible could be achieved without bringing about some serious Arab pushback.

It is Kessler’s view that it was during revolt that a strong sense of Arab nationalism in Palestine extended beyond the urban elites to all corners of the country. All segments of Arab society – urban and rural, rich and poor, rival families, and even to a large extent Muslim and Christian – united in the same cause against Zionism and against its perceived enabler, the British Empire. The Arab public in Palestine was becoming increasingly politically aware and consciously perceiving itself as a distinct entity – distinct from its brethren in Syria, in large part because it has a different foe: not simply European imperialism but this very specific threat presented by Zionism.

The British government made early efforts at keeping the peace, but these proved fruitless. And when the revolt erupted in 1936, it sent a royal commission to Palestine, known to history as the Peel Commission, to examine the causes of the revolt. It proposed in effect the first ‘two state solution.’ The Emir Abdullah of Transjordan publicly accepted this plan. The main rival clan to the Husseinis, the Nashashibis, privately signaled that they were amenable – not thrilled, but amenable. And their allies held the mayorships of many important cities – Jaffa, Haifa, and even Nablus, Jenin and Tulkarem, which today are centres of militancy. And yet the Mufti makes very clear that he regards this plan as a degradation and a humiliation, and all of these erstwhile supporters of partition suddenly realise that they are against partition.

Kessler believes that this is the point at which a certain uncompromising line became the default position amongst the Arab leadership of Palestine, with dire consequences for the Palestinians themselves, and when Yishuv leader David Ben Gurion saw an opportunity to achieve his long-standing objective of creating a self-sufficient Jewish polity, one that could feed itself, house itself, defend itself, employ itself, without any help from anyone – neither British or Arabs. When the Arabs called a general strike and boycott, cut all contacts with the Jewish and British economies and closed the port of Jaffa in Spring 1936, he lobbied successfully with the British to allow the Jews to open their own port in Tel Aviv, ultimately causing a lot of economic pain to the Arabs and helping the Jews in their state-building enterprise.

This is a mosaic history, capturing the chaotic events on the ground through snippets of action. And also, the people involved.

There are heroes and villains aplenty in this relatively untold story. The urbane and erudite nationalists Muhammed Amal and George Antonius who strive for middle ground against increasingly insurmountable odds, and who died alone and exiled having failed to head off the final showdown that is today known as Al Nakba. The farseeing, resolute, and humourless Ben Gurion and the affable, optimistic Chaim Weizmann, who became Israel’s first prime minister and president respectively. The New York born Golda Meyerson, more of a realist than either leader, who would also one day become prime minister. The irascible revisionist Vladimir Ze’ev Jabotinski, the forebear of today’s virulent rightwing nationalists

The hardliner Mufti Haj Amin al Husseini, whose uncompromising stance, malign political influence, and conspiratorial association with the Nazis set the stage for a long general strike, the Great Revolt, and ultimately, the débâcle of 1948. The flamboyant rebel leaders, Syrian Izz al Din al Qassam, who is memorialized in the name of the Hamas military wing and a Gaza-made rocket, and Fawzi al Qawuqji. Qassam was gunned down by British soldiers during the revolt whilst Qawuqji lived on to become one of the most effective militia leaders in the war of 1948, and to perish therein. Both are remembered today as Palestinian martyrs whilst the Mufti is an arguably embarrassing footnote of history. There’s an article about his relatively unremarked death at the end of this post.

And in the British corner, the well-intentioned high commissioners who vainly endeavoured to reconcile the claims of two aspirant nations in one tiny land, and quixotic figures like the unorthodox soldier Ord Wingate who believed he was fulfilling prophecy by establishing the nucleus of what would become the IDF (like many charismatic British military heroes, and particularly General Gordon and Baden-Powell, both admirers and detractors regarded him a potential nut-case); and the Australian-born ex-soldier Lelland Andrews, assistant district commissioner for Galilee, who also conceived of his mission as divinely ordained. Lewis was murdered by Arab gunmen and Wingate went down in an aeroplane over Burma during WW2.

There are appearances from among many others, Lloyd George, Winton Churchill and Neville Chamberlain, Adolph Hitler and Benito Mussolini, Franklin D Eisenhower and Joseph Kennedy.

The book highlights the work of powerful British functionaries in handling early confrontations: they are memorialized for starting commissions to study the matter and to generate ideas, though many of their ideas weren’t followed or were followed to ill effect. None solved the problem, making this account of the earliest days of the conflict all the more heartbreaking.

All under the shadow of the impending Shoah, and the inevitable showdown that would culminate in al Nakba.

The road to Al Nakba

Kessler argues that the Arab social fabric and economy are completely torn and shattered by the end of this revolt that in many ways the final reckoning for Palestine between Jews and Arabs – the civil war that erupts in 1947 – is actually won by one side and lost by the other nearly a decade earlier.

The final paragraphs of Kessler’s enthralling book are worth quoting because they draw a clear line between the events of the Great Revolt and the catastrophe, al Nakba, of 1948:

In so many ways, for both Israelis and Palestinians, this revolt rages on.

© Paul Hemphill 2024.

Kessler’s interview in Fathom e-zine follows, together with serval informative articles on the Great Revolt and its aftermath

For more on Israel and Palestine in In That Howling Infinite, see: A Middle East Miscellany

The picture at the head of this post shows British troops marching through Ibn Khatib Square in 1936 past King David’s Citadel and towards the Jaffa Gate

British policemen disperse an Arab mob during the Jaffa riots in April 1936 (The Illustrated London News)

An interview with Oren Kessler

Oren Kessler’s new book Palestine 1936: The Great Revolt and the Roots of the Middle East Conflict (Rowman & Littlefield, 2023) argues powerfully that events in Mandatory Palestine between 1936 and 1939 have shaped the subsequent history of the conflict for Israelis and Palestinians. Called ‘the definitive study’ by Michael Oren, Kessler’s book identifies the revolt as the true first intifada, an uprising which laid the ground for the Arab defeat in 1947-48 and which has set the tone of the conflict for almost a century. He sat down with Fathom deputy editor Jack Omer-Jackaman to discuss the book, recently released in the UK.

Jack Omer-Jackaman: The general reader, in English at least, has lacked a history of the Great Revolt and its repercussions. What have they been missing and with what consequences for our understanding of the conflict?

Oren Kessler: I argue that although this is an Arab revolt, it is as much a Jewish story as an Arab story. From the Arab perspective it’s an extremely formative event – it’s the crucible in which Palestinian Arab identity coalesced as virtually all strands of Arab society came together in a common purpose against a common foe. But on the Jewish side this is an equally seminal and decisive event. It’s often forgotten but this is the period in which the words ‘Jewish State’ first appear on the international agenda – not just the ‘national home’ promised in the Balfour Declaration, but a Jewish state to all intents and purposes, as part of a ‘two-state solution.’ It’s also the period in which the British Empire sows the seeds for a Jewish army. So, in all of these ways this is a hugely formative chapter in the history in the Land of Israel/Palestine, for the conflict itself, and for attempts to resolve it. The degree to which this chapter hasn’t gotten its due is actually quite startling. It’s not entirely clear to me why such a pivotal event right before the Second World War hasn’t gotten its due in English outside of a handful of academic works.

JOJ: And why has the 1936-1939 Revolt been relatively ignored?

OK: It’s a very good question. In the book I quote Professor Mustafa Kabha of the Open University of Israel, who argues that in the Palestinian narrative and consciousness, the revolt has been side-lined, marginalised by the overwhelming primacy of the Nakba. The Nakba is much ‘easier’ to fit into the narrative because, from the Palestinian perspective, it’s the moment at which they are betrayed and unjustly treated by Zionism, by British Imperialism, even by their fellow Arabs who fail to rescue them from the Zionist menace. Whereas dealing with 1936-39 requires a lot more soul-searching. There is a huge convulsion of Arab infighting in this period – there is much Arab bloodshed at the hands of fellow Arabs. That is a lot more difficult for a national narrative to rationalise.

Every national movement has its narrative and its storyline, and the Jewish national narrative tends to be quite forward moving: from the first wave of immigration in the late 19th Century, on to the Balfour Declaration, the start of the British Mandate and the Jewish state-building of the 1920s and 30s, then the agony of the Holocaust and finally the redemption of statehood. That’s essentially the Zionist story, and I think a large-scale, concerted nationalist uprising against that story is a somewhat unwelcome blip in the narrative arc.

JOJ: Let’s set the geopolitical scene at that time: talk to us about the connections between European and local events.

OK: Throughout the book, I bounce back and forth between the situations in Palestine and Europe, because they’re inseparable – certainly from a British perspective, and equally from a Jewish one. The revolt begins only three years after Hitler comes to power in Germany in 1933. There are also other antisemitic movements ascendent across Europe, in places like Poland, Hungary and Romania, and very many Jews are desperate to leave. But almost all potential sanctuaries in the world have been closed; the US has been almost closed to immigration since the Immigration Act of 1924. In many ways, Palestine is the only significant possible refuge left for the Jews of Europe. So Jewish immigration into Palestine is skyrocketing in these years – the Jewish population there doubles in the first half of the 1930s. In 1935, 60,000 Jews come into Palestine, which is nearly double that of the year before, so the Jews are approaching 30 per cent of the population by the time the revolt erupts. The revolt is thus a direct result of the European situation, since it’s very clear to the Arabs of Palestine that if things continue this way, Palestine will have a Jewish majority before long.

From a British perspective, the war clouds looming over Europe make it very difficult for the British army to quash the revolt. They simply don’t have the manpower for it, at least until the Munich Agreement of 1938, granting Hitler the Sudetenland. With the appeasement of Hitler, Britain and all of Europe breathe a sigh of relief and buy some time (at least that’s how it felt at the time). After Munich the British are able to send two divisions to Palestine, which constitutes the largest British army deployment in the interwar period. This is another reason it’s startling that this era has been so overlooked.

JOJ: That leads us neatly onto the next topic, which looks at the balance of power post and ante the revolt. How does each side – and let’s include the British – go into the period and how do they emerge?

OK: Until Munich, the British are severely undermanned in Palestine, and this directly benefits the Jews because this is the period in which the British finally accede to a long-standing demand by the Haganah – the Jewish self-defence group that is technically illegal but tolerated by the British – to arm and train Jews in large numbers. And that’s what happens: 15,000-20,000 Jews join the Palestine Police as Jewish Supernumerary Police. And though they receive their weapons, training and part of their salary from the British government, it’s clear to everyone that they’re ultimately answerable to the Haganah. So the Jews, led by David Ben-Gurion – already in this era the clear leader of Palestine’s Jews – are able to turn adversity to advantage and make tremendous gains, militarily and otherwise, throughout the Arab revolt.

it’s the mirror image for the Arab side. The revolt to crush Zionism crushes the Arabs instead. The initial unity of the revolt’s first phase under the leadership of Grand Mufti Hajj Amin al Husseini – which includes a six-month general strike – gives way in the second phase (from Autumn 1937) to a convulsion of infighting and score settling. Several thousand Arabs are killed by their fellow Arabs, and the Arab leadership – namely the mufti and his associates – is driven into exile. And of course the British begin taking very heavy-handed measures – including a number of incidents that qualify as atrocities – to quash the revolt. Huge numbers of Arab men are put in prison or killed by the British, and thousands of homes demolished. The Arab social fabric and economy are completely torn and shattered by the end of this revolt. I argue in the book, and this is an argument that has also been made by the Palestinian-American professor Rashid Khalidi, that in many ways the final reckoning for Palestine between Jews and Arabs – the civil war that erupts in 1947 – is actually won by one side and lost by the other nearly a decade earlier.

JOJ: The popular narrative is that Palestinian nationalism – as distinct from wider Arab or Syrian nationalism – was a product of the 1930s. What did your study of the period tell you about this?

OK: I think Palestine is sui generis in many ways, including the development of nationalism there. In my view it is during the Arab revolt that a strong sense of Arab nationalism in Palestine extends beyond the urban elites to all corners of the country. All segments of Arab society – urban and rural, rich and poor, rival families, and even to a large extent Muslim and Christian – unite in the same mission against Zionism and against its perceived handmaiden: the British Empire.

The Arab public in Palestine is growing increasingly politically aware and consciously perceiving itself as a distinct entity – distinct from its brethren in Syria, in large part because it has a different foe: not simply European imperialism but this very specific threat presented by Zionism.

JOJ: So was the 1936-1939 Revolt the crucial event in the origins of the modern Israeli-Palestinian conflict? Was this the point at which it became zero sum for both sides? Or was it just the first time there was a wider realisation of this?

OK: I’ve lost track of how many people who, when I start telling them about my book, assume I’m referring to the Hebron massacre of 1929. In my view the Hebron riots were just that: they were riots, they were an outburst of terrorism, but not a sustained nationalist uprising in the way that the Great Revolt of 1936 is – not an intifada in the parlance of today. I think in many ways, the Revolt is when both sides really come to see this conflict as zero sum. But it was always in a way zero sum in that whichever community has the demographic majority in Palestine would be the one that would determine its fate. This is an age in which the world is moving, however haltingly, from imperialism towards self-determination, and it is clear to both Jews and Arabs alike that having a majority would be absolutely key. However, in the 1920s, the Jews were so far from that majority that both sides were able to postpone the final reckoning. In the 1930s, the Jews are threatening to become a majority, and that’s the immediate precursor to this revolt erupting.

JOJ: Is it fair to say that the tone was set at this time, on the Palestinian side, for this being a conflict that demands hardliners? That the tone was set of leadership by extremists like Qassam and Hajj Amin[1] and not more moderate figures like Faisal or the Nashashibis?

OK: Yes, I do think that this is the period in which the intransigent line taken by Hajj Amin becomes not just mainstream but one from which it is very dangerous to deviate. Hajj Amin, even after fleeing the country in Autumn of 1937, manages to exert his will over the revolt from afar, and anyone who dares step out of line or contemplate reaching some sort of modus vivendi with the Zionist movement tends to find himself dead or in some other serious trouble. A prime example of that is the reaction among prominent Arabs to the partition plan. In late 1936, the British government sends a royal commission to Palestine, known to history as the Peel Commission, to examine the causes of the revolt, and famously it proposes the first ‘two state solution.’ The Emir Abdullah of Transjordan publicly accepts this plan. The main rival clan to the Husseinis, the Nashashibis, privately signal that they are amenable; not thrilled, but amenable. And their allies hold the mayorships of quite a few important cities – Jaffa, Haifa, and even Nablus, Jenin and Tulkarem, which today are centres of militancy. And yet the Mufti makes very clear that he regards this plan as a degradation and a humiliation, and all of these erstwhile supporters of partition suddenly realise that they are against partition. So yes, I do think that this is the point at which a certain uncompromising line becomes the default one amongst the Arab leadership of Palestine, with really devastating results for the Palestinians themselves.

JOJ: Let’s look to the Jewish side. Is it the first, or at least a formative, time when differing approaches to state-building and self-defence within the Zionist movement are clearly exposed?

OK: Absolutely. During the Arab Revolt the Haganah adheres to a policy called havlagah, meaning self-restraint, despite the revolt’s very high toll in Jewish blood. Some 500 Jews are killed in this revolt; these are huge numbers, comparable to those in the Second Intifada in much more recent times. The logic is to convince the British that they can be trusted with weapons and, as mentioned earlier, that’s exactly what happens. The Irgun – the Revisionist, right-wing dissident Zionist group, whose ideological leader is Vladimir Jabotinsky – has a very different view, much more in line with ‘an eye for an eye’. They believe that it has to be made very clear to the Arabs that Jewish blood could not be shed unanswered, and that taking the fight to the Arabs, including civilians, would have a deterrent effect. We see dozens of Irgun attacks targeting Arab civilians during the revolt. I don’t think there’s any other way to describe this than terrorism – this isn’t ‘collateral damage’ in an attempt to target militants, but a mentality in which ‘If the Arabs target our civilians, we’ll target theirs’. So, there’s a real schism between these two Zionist movements, but the Haganah are able to convince the British that they are in control and are the mainstream, and that the Irgun is merely a fringe group. And that’s how this crucial British-Jewish military cooperation begins.

JOJ: Could the Yishuv leadership have acted any differently in the years prior to the revolt and forestalled it? Or not without sacrificing immigration?

OK: A very good question, and one which gets back to this question of whether it’s a zero sum conflict. I don’t agree with the rose-tinted analyses of history that I sometimes hear, which claim that in the Ottoman and early Mandate eras the two communities were able to get along in peace and it is somehow British mismanagement that prompted the conflict. Rather it seems to me that when the Jews were a minority, they didn’t present too much of a disruption to the status quo, but as soon as they began to threaten to reach a majority, there is almost no alternative to this conflict breaking out. That’s how Ben-Gurion looks at this situation throughout, and he never agrees to even slowimmigration. By contrast, Chaim Weizmann, head of the world Zionist Organisation, is willing to slow immigration to try to cultivate Arab goodwill and cooperation. I don’t see how that objective of bringing as many Jews to the land as possible could be achieved without bringing about some serious Arab pushback.

JOJ: To what extent was the Arab general strike self-defeating in allowing Ben-Gurion unprecedented opportunities for a key Zionist priority: the conquest of labour?[2]

The general strike starts almost at the very beginning of the revolt and lasts six months – still one of the longest general strikes anywhere in history. It is a source of great Arab pride. As I mentioned, Ben-Gurion really is an expert in turning adversity into advantage. He sees a tremendous opportunity to achieve his long-standing objective of creating a self-sufficient Jewish polity, one that could feed itself, house itself, defend itself, employ itself, without any help from anyone – not the British or the Arabs. In the strike, the Arabs cut all contacts with the Jewish and British economies, and when Jaffa port closed in Spring of 1936, Ben-Gurion pleads successfully with the British to allow the Jews to open their own port in Tel Aviv. The British agree and Ben Gurion is euphoric, hailing the fact that the Jews now have an outlet to the world as a second Balfour Declaration. That’s just one example of how the Arab strike and boycott ultimately cause a lot of economic pain to the Arabs and help the Jews in their state-building enterprise.

JOJ: You benefited tremendously from the declassification of the Peel Commission’s secret testimonies, which threw up some fascinating revelations. What did we learn about the origins of the Balfour Declaration, for example?

This was one of the most interesting troves of archival documents that I found in my research. The British Government kept the Peel Commission documents classified for 80 years, and they were very quietly declassified only in 2017. I wrote an article in Fathom in 2020 about the 1937 secret testimony of David Lloyd George, the Prime Minister at the time of the Balfour Declaration, on why the government had issued that historic and controversial document. Explaining his decision of two decades earlier, he says the Jews ‘are a dangerous people to quarrel with, but they are a very helpful people if you can get them on your side.’ He says that he and his ministry were very concerned, in the midst of the First World War, that the Jews of America and Russia might not support the allies but go over to the German side. There were even murmurings that the Germans were thinking of a ‘Balfour Declaration’ of their own. Lloyd George makes very clear in this testimony that that was a primary reason that the Declaration was given at that time. And he says that, in his opinion, the declaration more than paid for itself by the help that the Jews of America and Russia gave in various ways during the war.

JOJ: Herbert Samuel’s testimony was interesting, too.

OK: Samuel was the first High Commissioner for Palestine, as well as a Jew and a Zionist. In his testimony he is asked why he appointed Hajj Amin as Grand Mufti in the first place in the early 1920s – this is the only occasion I’ve ever seen him asked about this decision, which is one of the most fateful taken in the entire history of the Israeli-Arab conflict. He basically says, and I’m paraphrasing: ‘look, I had no choice. We had to appoint someone from the Husseini family because we had already given the other great Arab families various other perks, and so the Husseinis needed to get the muftiship. And Amin was the only Husseini with the requisite religious education having studied at al Azhar in Egypt.’ Samuel doesn’t admit it was a mistake but defends the decision and says that Hajj Amin had more or less behaved well until that point. (That is not quite true: the British had sentenced him in absentia for rabble rousing in 1920.) These are fascinating documents that were originally slated for destruction; the witnesses who give testimony do so on that understanding. But one very forward-looking British official has the foresight to stow them away, scribbling in the margins that they chronicle ‘an important chapter in the history of Palestine and the Jewish people, and will, no doubt, be of considerable value to the historians of the remote future.’

JOJ: Let’s look at Peel’s partition proposals a little deeper. We tend, optimistically, to think that decisions taken by high level politicians and civil servants are subject to forensic detail and informed by expert knowledge. How does the British process for proposing the first two-state solution correct us on this?

OK: That is one of the most fascinating discoveries contained in the secret testimonies: just how this two-state solution is arrived at. One of the commission members is an Oxford don by the name of Professor Reginald Coupland, an Africa-focused historian not particularly well-versed in the Middle East. He arrives at the idea that just as the Greeks and Turks were separated after World War One, in what he referred to as a ‘clean cut’, so Jews and Arabs need to be separated in that same way. It is really Coupland, with the help of a few British colonial servants in Palestine, who pushes through this idea of a two-state solution. And they do so quite hastily – when you look at the minutes of these secret testimonies, it’s just a few pages in which they discuss the practicability and the details of such a solution. It’s Coupland, an irrigation advisor by the name of Douglas Harris, and the assistant district commissioner for Galilee, Lewis Andrews (who shortly thereafter is assassinated) who draft the first two-state solution, which becomes the ideological template for every subsequent attempted solution to the conflict, from the UN’s exactly a decade later onto the various subsequent iterations until our time.

JOJ: Let’s talk about another piece of Mandate administration, the 1939 MacDonald White Paper, which barred Jews entry to Palestine just months before the outbreak of World War Two. Does your book have anything to say on this that is new?

OK: There’s a general familiarity, at least among Jews, with the White Paper and that it is a bad an unjust thing. But the genesis of the White Paper has not been researched to the degree it deserves, and in the book I devote a whole chapter to it. The Colonial Secretary at the time is Malcolm MacDonald, who is only 37 years old (he is the son of the first Labour Prime Minister, Ramsay MacDonald). This is the Chamberlain government, which is dedicated to appeasement, not just in Europe but in the Middle East. Even though MacDonald is a member of the National Labour Party, he is a loyal member of the ministry and determines, with the advice of senior officials in the army and the government, that some drastic changes need to be made to Britain’s Palestine policy in such a crucial period. There is a feeling that world war would break out at any point and that Muslim opinion, particularly in India, has to be appeased, lest Muslim subjects of the empire side with Hitler.

When you look at the discussion, you see that the British policy makers plan to go far in the direction of Arab demands when they call the St James’s Conference in 1939. And yet, throughout these negotiations, they go quite a bit farther even than they originally intend. So, where 60,000 Jews immigrated to Palestine in 1935, the 1939 White Paper limits Jewish immigration to a total of 75,000 over five years, after which Palestine would become an independent state. The White Paper doesn’t say an independent Arab state, but of course if Jewish immigration is limited to keep the Jews under 35 or 40 per cent of the population, it’s clear to everyone that this would be a de facto Arab state. This is mid-1939, when the Jews of Europe are most desperate to find sanctuary outside of Europe, and the White Paper is seen by the Jews and their supporters as a tremendous betrayal, and a reneging not just on the Peel Commission plan of two years previous, but on the Balfour Declaration itself.

This is one of the tremendous ‘what ifs’ of history: what would have happened had the White Paper not been passed, or had the Peel partition plan of 1937 gone through? Ben-Gurion, after the Holocaust, said that had the Jews had the small state promised to them in 1937, six million could have been saved. I think that’s perhaps an overstatement: I’m not sure that the very small state offered to them was developed enough to absorb six million people. It was Golda Meir who said that had the Jewish state been established (and the White Paper not implemented), hundreds of thousands could have been saved: I think that’s a plausible reading of history. The White Paper is what finally turns Ben-Gurion against the British. It’s when he decides that the British-Zionist partnership is essentially over and when he starts to look across the ocean to America as the great potential supporter of Zionism.

JOJ: Finally, it’s fascinating to see how the 1936-1939 Revolt and this period lives in the iconography of both Israelis and Palestinians. You don’t have to look too hard to see it referenced or deployed in the present day. It occupies a place of glory for Palestinians, which is rather ironic given its role in the catastrophe of 1948. And on the Israeli side, it was referenced not too long ago by Finance Minister Bezalel Smotrich.

OK: I argue that the revolt has cast its shadow over the Israeli-Palestinian conflict ever since – for the Arabs, for the Jews, and for attempts to resolve the conflict. Just recently, for example, in the Gaza conflict of May 2021, you may remember that the war extended to the battlefield of social media. When the Arabs of Israel and the West Bank joined together in a one-day strike, Twitter was abuzz with comparisons to 1936. And, as you mention, Bezalel Smotrich tweeted: ‘the riots of the Arab enemy take us back many years to the great Arab revolt. Back then a hostile British government protected rioters. Today a worthless, weak Jewish government, a contaminated judiciary and a law enforcement system emasculated by dangerous post-national and post-modern notions…’ Palestinian folk songs still celebrate the revolt, and in my view the BDS movement is a direct descendant of the general strike. Finally, as I mentioned earlier, the two-state solution that is still the international community’s the favoured solution to the conflict is simply a variation of the original partition plan of 1937. In so many ways, for both Israelis and Palestinians, this revolt rages on.

[1] Editor’s note: Hajj Amin al Husseini, appointed by the British Mandate as Grand Mufti in 1921, would become a determined supporter of Nazi Germany. At his 1941 meeting with Hitler, Hajj Amin declared himself ‘fully reassured and satisfied’ with Hitler’s reassurance that once having achieved the ‘total destruction of the Judeo-Communist empire in Europe… Germany’s objective would then be solely the destruction of the Jewish element residing in the Arab sphere’. In 1943, the SS enlisted Hajj Amin to lead a recruitment drive among Bosnian Muslims, SS Main Office Chief Berger noting the ‘extraordinarily successful impact’ of the Mufti’s activities.

[2] Editor’s note: The concept of Kibbush Haavoda, the conquest of labour, was a key plank in Labour Zionism. Its priorities were the encouraging of manual and agricultural labour amongst Jewish immigrants to Palestine and a reliance on Jewish labour for the Jewish economy

THE MUFTI OF JERUSALEM, SAYID AMIN AL HUSSEINI, MEETS WITH HITLER, NOVEMBER 1941.

Iraq won limited independence in 1932, just before the Nazis came to power. When the Mufti ensconced himself in Iraq seven years later, the country was under nominally ‘pro-British’ Prime Ministers, and Regent ‘Abd al-Ilah for the four-year-old king, Faisal II. This uneasy British-Iraqi equilibrium ended on first day of April 1941, when four Iraqi officers known as the Golden Square, wanting full independence (and similarly aligning themselves with the fascists in the foolish belief that doing so would help them get it), staged a coup d’état. It lasted two months. British troops ousted the coup on the first day of June — and as they did, anti-Jewish riots rocked Baghdad. An estimated 180 Jewish Iraqis were killed and 240 wounded in this pogrom known as the Farhud.

Why would the momentary power vacuum of the British takeover lead to anti-Jewish terror? While doing research for my 2016 book, State of Terror, I was intrigued by the claim of one Iraqi Jewish witness, Naeim Giladi, that these ‘Arab’ riots were orchestrated by the British to justify their return to power.[3] Indeed, the riots seemed unnatural in a society where Jews had lived for two and a half millennia, and the “pro-Axis” Golden Square takeover two months earlier had not precipitated any such pogrom. Yet it was also true that Zionism had created ethnic resentment, and Giladi did not question that junior officers of the Iraqi army were involved in the violence. The evidence provided by Giladi was compelling enough to seek out clues among British source documents that were not available to him.

And that, along with the hope of shedding new light on the Mufti’s pro-fascist activities, brought me to the archive at issue and my qualified (redacted) success in getting the first part declassified– officially titled, CO 733/420/19. Not surprisingly, much of the file focused on legitimate worry over the Mufti’s dealings with the Italian fascists. Some of the British voices recorded considered him to be a serious threat to the war effort, and a report entitled “Inside Information” spoke of the Mufti’s place in an alleged “German shadow government in Arabia”. Others dismissed this as “typical of the sort of stuff which literary refugees put into their memoirs in order to make them dramatic” and suggested that the Mufti’s influence was overstated.

Whatever the case, by October 1940, the Foreign Office was considering various methods for “putting an end to the Mufti’s intrigues with the Italians”, and by mid-November,

it was decided that the only really effective means of securing a control over him [the Mufti] would be a military occupation of Iraq.

British plans of a coup were no longer mere discussion, but a plan already in progress:

We may be able to clip the Mufti’s wings when we can get a new Government in Iraq. F.O. [Foreign Office] are working on this”.

So, the British were already working on re-occupying Iraq five months before the April 1941 ‘Golden Square’ coup.

A prominent thread of the archive was: How to effect a British coup without further alienating ‘the Arab world’ in the midst of the war, beyond what the empowering of Zionism had already done? Harold MacMichael, High Commissioner for Palestine, suggested the idea “that documents incriminating the Mufti have been found in Libya” that can be used to embarrass him among his followers; but others “felt some hesitation … knowing, as we should, there was no truth in the statement.”

But frustratingly, the trail stops in late 1940; to know anything conclusive we need the second part’s forbidden ten pages: CO 733/420/19/1.

The redacted first part partially supports, or at least does not challenge, Giladi’s claim. It proves that Britain was planning regime change and sought a pretext, but gives no hint as to whether ethnic violence was to be that pretext. Interestingly, Lehi had at the time reached the same conclusion as Giladi: its Communique claimed that “Churchill’s Government is responsible for the pogrom in Baghdad”.[4]

Does the public have the right to see still-secret archives such as CO 733/420/19/1? In this case, the gatekeepers claimed to be protecting us from the Forbidden Fruit of “curiosity”: They claimed to be distinguishing between “information that would benefit the public good”, and “information that would meet public curiosity”, and decided on our behalf that this archive fit the latter.[1] We are to believe that an eight-decade-old archive on an important issue remains sealed because it would merely satisfy our lust for salacious gossip.

Perhaps no assessment of past British manipulation in Iraq would have given pause to the Blair government before signing on to the US’s vastly more catastrophic Iraqi ‘regime change’ of 2003, promoted with none of 1940’s hesitation about using forged ‘African’ documents — this time around Niger, instead of Libya. But history has not even a chance of teaching us, if its lessons are kept hidden from the people themselves.

Note: According to Giladi, the riots of 1941 “gave the Zionists in Palestine a pretext to set up a Zionist underground in Iraq” that would culminate with the (proven) Israeli false-flag ‘terrorism’ that emptied most of Iraq’s Jewish population a decade later. Documents in Kew seen by the author support this. But to be sure, the Zionists were not connected with the alleged British maneuvers of 1941.

1. Correspondence from the UK government, explaining its refusal to allow me access to CO 733/420/19/1:

Section 23(1) (security bodies and security matters): We have considered whether the balance of the public interest favours releasing or withholding this information. After careful consideration, we have determined that the public interest in releasing the information you have requested is outweighed by the public interest in maintaining the exemption. It is in the public interest that our security agencies can operate effectively in the interests of the United Kingdom, without disclosing information that would assist those determined to undermine the security of the country and its citizens.

The judiciary differentiates between information that would benefit the public good and information that would meet public curiosity. It does not consider the latter to be a ‘public interest’ in favour of disclosure. In this case, disclosure would neither meaningfully improve transparency nor assist public debate, and disclosure would not therefore benefit the public good.

2. Ben-Gurion looked ahead to when the end of the war would leave Britain militarily weakened and geographically dispersed, and economically ruined. He cited the occupation of Vilna by the Poles after World War I as a precedent for the tactic. For him, the end of WWII only presented an opportunity for the takeover of Palestine with less physical resistance; it also left Britain at the mercy of the United States for economic relief, which the Jewish Agency exploited by pressuring US politicians to make that assistance contingent on supporting Zionist claims to Palestine. At a mid-December 1945 secret meeting of the Jewish Agency Executive, Ben-Gurion stressed that “our activities should be directed from Washington and not from London”, noting that “Jewish influence in America is powerful and able to cause damage to the interests of Great Britain”, as it “depends to a great extent on America economically” and would “not be able to ignore American pressure if we succeed in bringing this pressure to bear”. He lauded Rabbi Abba Silver in the US for his aggressiveness on the issue, while noting that he was nonetheless “a little fanatical and may go too far”. (TNA, FO 1093/508). The Irgun was more direct in 1946, stating that Britain’s commuting of two terrorists’ death sentences and other accommodations to the Zionists “has been done with the sole purpose to calm American opposition against the American loan to Britain”. (TNA, KV 5-36). Meanwhile, in the US that year Rabbi Silver’s bluntness on the tactic worried Moshe Shertok (a future prime minister). Although like Ben-Gurion, Shertok said that “we shall exploit to the maximum the American pressure on the British Government”, in particular the pre-election period (and in particular New York), but urged “care and wisdom in this” so as not to give ammunition to “anti-Zionists and the anti-semites in general”. Shertok criticized Silver for saying publicly that “he and his supporters opposed the loan to be granted to the British Government”. (TNA, CO 537/1715)

3. Suárez, Thomas, State of Terror: How Terrorism Created Modern Israel[Skyscraper, 2016, and Interlink, 2017]; In Arabic, هكذا أقيمت المستعمرة [Kuwait, 2018]; in French, Comment le terrorisme a créé Israël[Investig’Action, 2019]

Giladi, Naeim, Ben-Gurion’s Scandals: How the Haganah and the Mossad Eliminated Jews [Dandelion, 2006]

4. Lehi, Communique, No. 21/41, dated 1st of August 1941

Update: This post originally referred to the “four-year-old Prime Minister, ‘Abd al-Ilah,” not the four-year-old King Faisal under Regent ‘Abd al-Ilah. Commenter Jon S. corrected us, and the post has been changed.

The day the Mufti died

Yes, Hajj Amin al-Husayni collaborated with the Nazis, but that’s not why he was dropped from the Palestinian narrative

Martin Kramer, Times of Israel Blogs, July 5, 202

Please note that the posts on The Blogs are contributed by third parties. The opinions, facts and any media content in them are presented solely by the authors, and neither The Times of Israel nor its partners assume any responsibility for them. Please contact us in case of abuse. In case of abuse,

“To His Eminence the Grand Mufti as a memento. H. Himmler. July 4, 1943.” Israel State Archives.

Fifty years ago, on July 4, 1974, Hajj Amin al-Husayni, the “Grand Mufti” of Jerusalem, passed away in Beirut, Lebanon, at the American University Hospital. At age 79, he died of natural causes. The Mufti had faded from the headlines a decade earlier. In 1961, his name had resurfaced numerous times during the Jerusalem trial of Adolf Eichmann. But a couple of years later, the Palestinian cause gained a new face in Yasser Arafat. With that, the Mufti entered his final eclipse.

When he died, the Supreme Muslim Council in Jerusalem asked the Israeli authorities for permission to bury him in the city. Israel refused the request. Any Palestinian who wanted to attend the funeral in Lebanon would be allowed to do so, but the Mufti of Jerusalem would not be buried in Jerusalem. Instead, the Mufti was laid to rest in the Palestinian “Martyrs’ Cemetery” in Beirut.

The Mufti was appointed to his position by the British in 1921. Within the British Empire, authorities preferred to work through “native” institutions, even if they had to create them on the fly. So they established a supreme council for Palestine’s Muslims and placed the Mufti at its helm. Although he lacked religious qualifications, he came from a leading family and appeared capable of striking deals.

In fact, he used his position to oppose the Jewish “National Home” policy of the Mandate. The “Arab Revolt” of 1936 finally convinced the British that he had to go, and in 1937 he fled the country.

After a period in Lebanon, he ended up in Iraq, where he helped foment a coup against the pro-British regime. When British forces suppressed the coup, he fled again, making his way through Tehran and Rome to Berlin. There, the Nazi regime used him to stir up Arabs and Muslims against the Allies. He was photographed with Hitler and Himmler, recruited Muslims to fight for the Axis, and attempted to secure promises of independence for colonized Arabs and Muslims. None of his efforts met with much success. His role, if any, in the Holocaust is a contested matter. Hitler and his henchmen hardly needed any prompting to execute their genocidal plans. Clearly, though, the Mufti rooted for Jewish destruction from the fifty-yard line.

After the Nazi collapse, he fell into French hands and spent a year in comfortable house detention near Paris. Later, he fled to Egypt and subsequently moved in and out of Syria and Lebanon. Following the Arab debacle of 1948, Egypt established an “All Palestine Government” in the refugee-choked Gaza Strip, leaving the presidency open for the Mufti. It didn’t last long. He continued to maneuver through Arab politics, but he was yesterday’s man to a new generation of Palestinians born in exile. During the Eichmann trial, the prosecution sought to implicate the Mufti as an accomplice. Yet the Mossad never came after him, and he didn’t die a martyr’s death.

Man without a country

The Mufti was a formidable politician. In 1951, a State Department-CIA profile of him opened with this evocative enumeration of his many talents, which is worth quoting at length:

King of no country, having no army, exiled, forever poised for flight from one country to another in disguise, he has survived because of his remarkable ability to play the British against the French, the French against the British, and the Americans against both; and also because he has become a symbol among the Arabs for defending them against the Zionists. His suave penchant for intrigue, his delicate manipulation of one Arab faction against another, combined with the popularity of his slogan of a united Muslim world, has made him a symbol and a force in the Middle East that is difficult to cope with and well nigh impossible to destroy. The names of Machiavelli, Richelieu, and Metternich come to mind to describe him, yet none of these apply. Alone, without a state, he plays an international game on behalf of his fellow Muslims. That they are ungrateful, unprepared, and divided by complex and innumerable schisms, does not deter him from his dream.

Profilers would later write similar things about Arafat, but the Mufti had none of Arafat’s cultivated dishevelment. He was manicured, even chic:

The Mufti is a man of striking appearance. Vigorous, erect, and proud, like a number of Palestinian Arabs he has pink-white skin and blue eyes. His hair and beard, formerly a foxy red, is now grey. He always wears an ankle length black robe and a tarbush wound with a spotless turban. Part of his charm lies in his deep Oriental courtesy; he sees a visitor not only to the door, but to the gate as well, and speeds him on his way with blessings. Another of his assets is his well-modulated voice and his cultured Arabic vocabulary. He can both preach and argue effectively, and is well versed in all the problems of Islam and Arab nationalism. His mystical devotion to his cause, which is indivisibly bound up with his personal and family aggrandizement, has been unflagging, and he has never deviated from his theme. For his numerous illiterate followers, such political consistency and simplicity has its advantages. The Mufti has always known well how to exploit Muslim hatred of ‘infidel’ rule.

So why did the Mufti fade into obscurity? (By 1951, he was on his way out.) Many mistakenly believe his collaboration with Hitler and the Nazis discredited him. It didn’t. Not only did the Arabs not care, but Western governments eyed the Mufti with self-interest. The general view in foreign ministries held that he had picked the wrong side in the war, but not more than that.

The above-quoted American report expressed this view perfectly: “While the Zionists consider him slightly worse than Mephistopheles and have used him as a symbol of Nazism, this is false. He cared nothing about Nazism and did not work well with Germans. He regarded them merely as instruments to be used for his own aims.” If so, why not open a discreet line to him and let him roam the world unimpeded?

Nakba stigma

What finally discredited the Mufti in Arab opinion, where it mattered most, was his role in the 1948 war. It was a war he wanted and believed his side would win. In late 1947, the British sent someone to see if there might be some behind-the-scenes flexibility in his stance on partition, which he had completely rejected. There wasn’t. He explained:

As regards the withdrawal of British troops from Palestine, we would not mind. We do not fear the Jews, their Stern, Irgun, Haganah. We might lose at first. We would have many losses, but in the end we must win. Remember Mussolini, who talked of 8,000,000 bayonets, who bluffed the world that he had turned the macaronis back into Romans. For 21 years he made this bluff, and what happened when his Romans were put to the test? They crumbled into nothing. So with the Zionists. They will eventually crumble into nothing, and we do not fear the result, unless of course Britain or America or some other Great Power intervenes. Even then we shall fight and the Arab world will be perpetually hostile. Nor do we want you to substitute American or United Nations troops for the British. That would be even worse. We want no foreign troops. Leave us to fight it out ourselves.

This underestimation of the Zionists proved disastrous, even more so than his overestimation of the Axis. He later wrote his memoirs, blaming “imperialist” intervention, Arab internal divisions, and world Zionist mind-control for the 1948 defeat. To no avail: his name became inseparable from the Nakba, the loss of Arab Palestine to the Jews. His reputation hit rock bottom, along with that of the other failed Arab rulers of 1948.

Upon his death in 1974, he received a grand sendoff in Beirut from the PLO. In 1970, Arafat had transferred the PLO headquarters from Jordan to Lebanon, and the funeral finalized his status as the sole leader of the Palestinian people. Four months later, Arafat addressed the world from the podium of the UN General Assembly, achieving an international legitimacy that the Mufti could never have imagined.

The PLO then dropped the Mufti from the Palestinian narrative; nothing bears his name. Even Hamas, which inherited his uncompromising rigidity and Jew-hatred, doesn’t include him in their pantheon. (Their man is Izz al-Din al-Qassam, a firebrand “martyr” killed by the British in 1935.)

If anyone still dwells on the Mufti, it’s the Israelis, including their current prime minister, who find him useful as a supposed link between the Palestinian cause and Nazism. One can understand Palestinians who push back on this; the Mufti was no Eichmann. But that doesn’t excuse Palestinian reluctance to wrestle candidly with the Mufti’s legacy. He personified the refusal to see Israel as it is and an unwillingness to imagine a compromise. Until Palestinians exorcise his ghost, it will continue to haunt them.

“VISIT OF H.R.H. PRINCESS MARY AND THE EARL OF HARWOOD. MARCH 1934. PRINCESS MARY, THE EARL OF HARWOOD, AND THE GRAND MUFTI, ETC. AT THE MOSQUE EL-AKSA [I.E., AL-AQSA IN JERUSALEM].” LIBRARY OF CONGRESS, LC-M33- 4221.

“VISIT OF H.R.H. PRINCESS MARY AND THE EARL OF HARWOOD. MARCH 1934. PRINCESS MARY, THE EARL OF HARWOOD, AND THE GRAND MUFTI, ETC. AT THE MOSQUE EL-AKSA [I.E., AL-AQSA IN JERUSALEM].” LIBRARY OF CONGRESS, LC-M33- 4221.

3 Comments