So we march to the rhythm of the revolution;

Oh it is our shining hour.

Move to the rhythm of the revolution,

And the revolution’s power.

Run with the rhythm of the revolution,

Storm the palace, seize the crown.

Rise to the rhythm of the revolution,

Shake the system, break it down!

Paul Hemphill, Rhythm of the Revolution

Recent events in the Middle East seem to validate Vladimir Lenin’s aphorism, “there are decades where nothing happens; and there are weeks where decades happen”.

”For years” wrote Bel Tru, the Independent’s correspondent in the Levant, a worthy successor to the late Robert Fisk and now retired Patrick Cockburn.East, “the world forgot about Syria. Many believed it was lost in an unsolvable abyss following the collapse of the 2011 revolution into a bloody civil war – made increasingly complex by the intervention of a mess of internal and international actors. Most assumed that the immovable regime of Bashar al-Assad had won, and that nothing would ever change. Few could even tell you if the war was still ongoing, let alone what stage it was at”.

Until Syrian rebel fighters stormed out of their fastness in Idlib province, which had been besieged and contained and for years by government forces and Russian bombers, and in an off sense that too the world by surprise, they took control of Aleppo, Syria’s largest city?

Over the space of a week, it seemed as if the nightmares of the past had come rushing into the present as the current wars in Gaza and Lebanon were pushed to the sidelines.

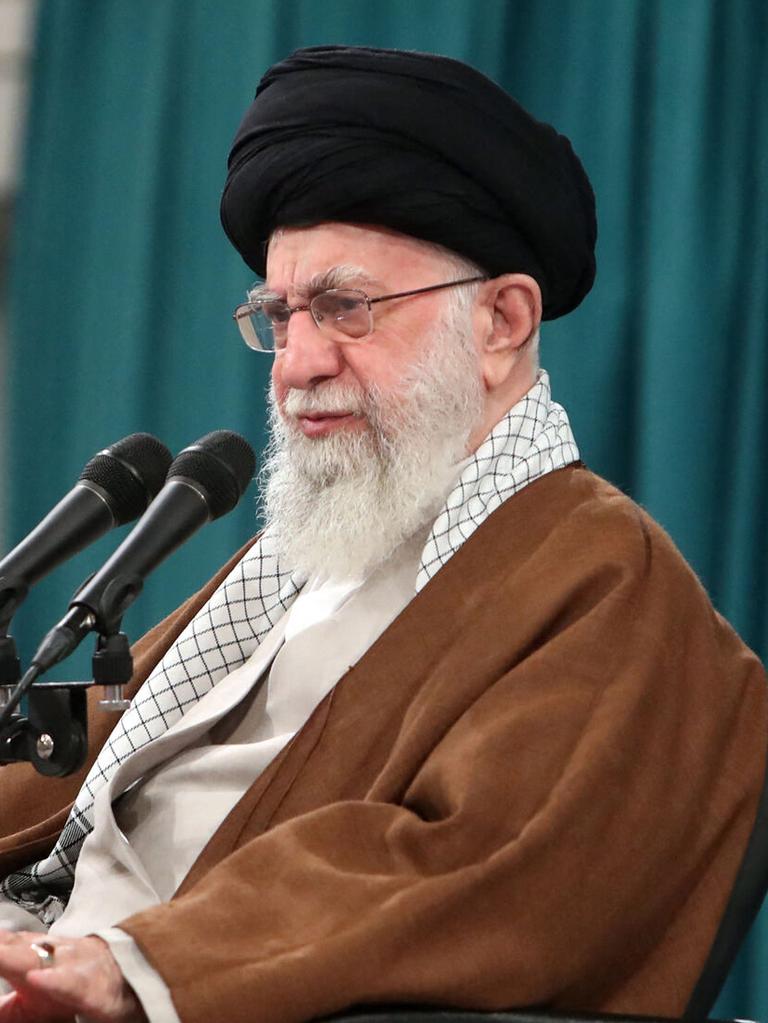

Iran’s theocratic tyrant Ayatollah Khamenei declared that the rebel offensive that destroyed the 52-year-old Assad dynasty in a mere eleven days was all a foreign plot concocted by the Great Satan and the Little Satan, aided and abetted by the wannabe Sultan of Türkiye (and there might indeed be a kernel of truth in that). In his opinion, it had nothing to do with the fact that the brutal and irredeemably corrupt Syrian regime was rotten to its core and that like the Russian army in 1917, its reluctant conscript soldiers, neglected, poorly paid and hungry, refused to fight for it whilst its commanders ran for their lives. Built to fight Israel and then to subdue Syrians, it had over time ate itself in corruption, neglect and ineptitude. Western radicals of the regressive left will doubtless believe the good ayatollah because that is what they are conditioned to believe rather than learning anything about Syria or the region generally.

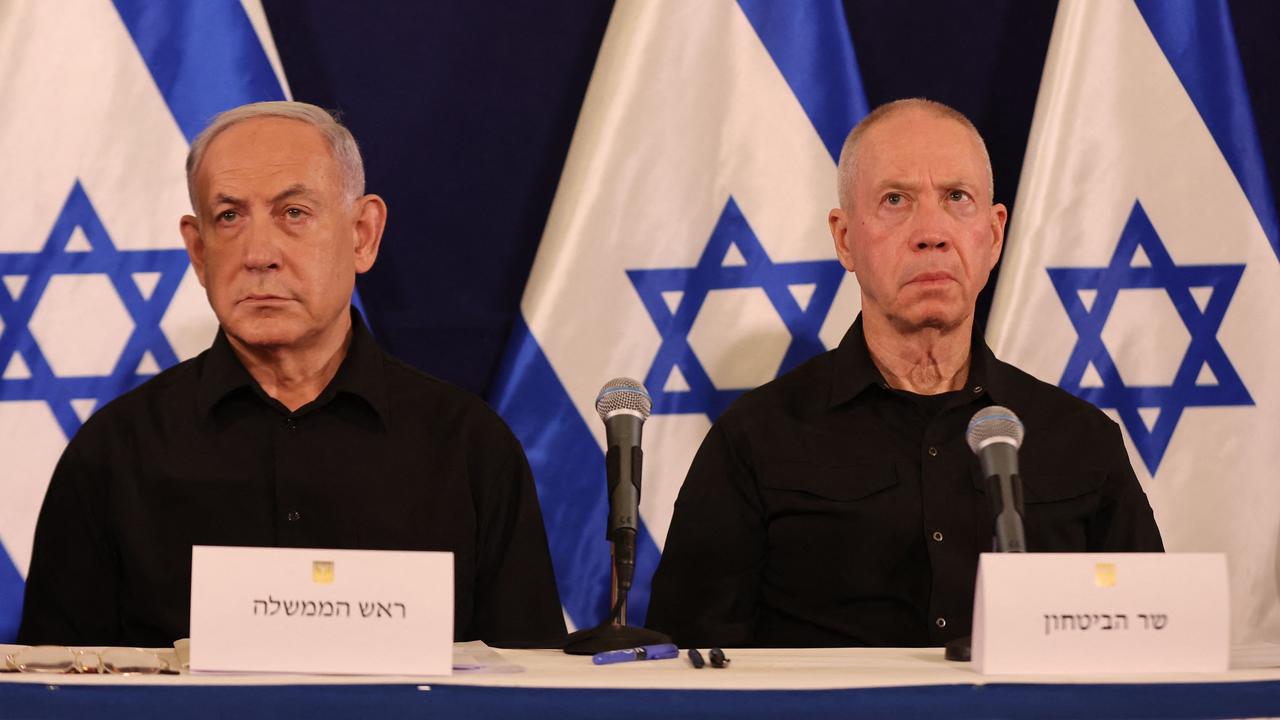

if Khamenei could only have removed the mote from his eye, he’d have seen that the fall of Bashar al Assad was the indirect result of the most disastrous series of foreign policy miscalculations since the theocratic regime took power in Tehran in 1979. In the wake of Hamas’s murderous attack on Israel on October 7, 2023, Iran made the fatal error of ordering its proxy Hezbollah in Lebanon to begin a low-level war against northern Israel, lobbing missiles and drones into it almost daily. What Tehran did not calculate was that once Israel had largely destroyed Hamas in Gaza it would turn its guns on to Hezbollah with stunning force. The indirect effect of Iran’s miscalculation was that neither Hezbollah nor Iran was in a position to help Assad repel the rebels when they launched their assault. Iran has now lost its regional ally Syria, in addition to Hezbollah and Hamas, leaving it unusually isolated in the region when its ageing clerical leadership is increasingly unpopular with its own people.

Over the coming weeks and months, commentators, pundits and so-called experts will ruminate on the causes of the fall of one of the Middle East’s most enduring and also, even by the region’s low standards, brutal regime, and on what may or may not happen now.

I republish below two excellent opinion pieces offering some answers to each question respectively. Each in their own way follow the advice of most scholars of the Middle East: expect the unexpected. And whilst most observers admit to having been taken by surprise when Hayat al Tahrir al Sham fell upon Aleppo, including intelligence organizations that ought to have known better, none were perhaps more surprised than the insurgents themselves when only a fortnight ago, they were given the nod by their Turkish patron to endeavour to expand the borders of their statelet and suddenly found themselves on an almost empty highway to Damascus.

Analyst and commentator David McCullen (who has featured prominently on this blog in the past) examines warning signs that may have indicated that all was not well in the Assad kingdom, drawing on on historical parallels to explain why the Bashar al Assad and his longtime all-pervasive and ever-watching security apparatus failed to see the gathering storm unlit it had engulfed them.

He references particularly the political scientist Timur Kuran, the originator of the concept of “preference cascade”: “… under repressive regimes (or ostensibly democratic ones that censor dissent) the gap between public pronouncements and private opinions increases over time, until many individuals dissent from the approved narrative and lose faith in institutions that promote it but remain reluctant to reveal their real views. This “preference falsification” creates a deceptive impression of consensus. It can make regimes believe they have more support than they really do, while convincing dissidents they are all alone so there is no point expressing a contrary opinion. But when an unexpected shock reduces the regime’s power to suppress dissent, people suddenly feel empowered to express their real opinions. They realise these opinions are widely shared and the false consensus evaporates. This can trigger a “preference cascade”, where individuals or institutions suddenly change sides and support for the government collapses overnight”.

Kilcullen concludes: “Given the speed and totality of Assad’s collapse, some observers seem to be assuming that HTS will now, by default, become the dominant player in Syria. On its face, this may seem a reasonable assumption, given what happened in similar situations – Havana 1959, Saigon 1975, Kabul 2021 and so on”. But he cautions that “it would be premature in Syria’s case since the war is very much ongoing. As the northern hemisphere winter closes in and Western allies prepare for a change of administration in Washington, Syria – along with Gaza, Lebanon, the Red Sea, Ukraine, Taiwan and the Korean peninsula – will remain a major flashpoint into the new year”.

Indeed, the immediate future is far from clear. It is axiomatic to say that most commentators who say they understand what is going to happen in the Levant often don’t. To quote B Dylan, something’s happening, and we don’t yet know what it is …

In the second article republished below, Israeli commentator Zvi Bar’el examines possibilities, including the Herculean task of putting the fractured state of Syria back together again. As Australian diplomat David Livingstone wrote in the Sydney Morning Herald on 3 December, “Syria and its conflict is a mosaic of combatants rather than a dichotomy of good versus evil. Loyalties usually reflect a person’s religion or ethnicity. The Sunnis hate the nominally Shiite regime of Assad; Assad himself is the inheritor of atrocities by his father’s regime against the Sunni, including the destruction of Hama and slaughter of many of its inhabitants in 1982; the Kurds want an autonomous homeland; and the Turkmen are no friends to Assad or extremist Sunnis”.

So, where to from here? Syria now pauses at a crossroads, where both hope for a better future, and scepticism that it will be achieved, are equally warranted. Whether or not the new Syrian regime can succeed is an open question.

There is much to be done, with little time and meagre resources to do it. Forces, factions and faiths will now have to be reconciled. The divided country is shattered physically, economically and psychologically. Some 410,000 Syrians are estimated to have been killed in war-related violence up to the end of last year making it the bloodiest conflict of the 21st century to date. The dead will have to counted and accounted for, including tens and tens of thousands lost in the regime’s jails and prisons, and the survivors of rehabilitated. Scores may have to be settled either in blood or in spirit. About half of the country’s pre-war population has either fled abroad or internally displaced. The new government will need to ensure civilians’ safety, enable the return of millions of refugees and internally displaced, and rehabilitate the infrastructure and civil services. But the country is broke, while one economist estimates that the physical damage across the country amounts to $150 billion.

What form will a government take? Does the new administration intend to hold elections? Will HTS leader Ahmed al Shara and his comrades set up a government that will be agreed on by all the communities, factions, militia, and foreign forces? Will the new constitution be Islamic? To this his new prime minister replies, “God willing, but clearly all these details will be discussed in the constitutional process.” When Italian journalist Andrea Nicastro asks him “do I understand correctly when I say you’re ready to make peace with Israel and that you’re hostile to Iran, Hezbollah and Russia?” Al-Bashir thanks him and leaves without answering.

Meanwhile, Arab states, who once spurned Assad’s regime and were tentatively cozying up to him only recently, having invited Syria back into the Arab League. European states are contemplating whether or not to remove HTS from their lists of proscribed terrorist organizations. Assad’s erstwhile backers, Iran and Russia, which in fact controlled large parts of Syria, left Dodge in haste and are now replaced by two new-old occupiers, Israel, and Turkey. One took over the “Syrian Hermon” and a little further – to the condemnation of Arab regimes and the United Nations, the other is completing the occupation of the Kurdish regions in northern Syria.

No love is lost between the two of them, but it seems fate insists on making them meet in war fronts. As Bar’el adds, “… once as partners when they helped Azerbaijan in its war against Armenia and once as enemies in the Gaza front or now on Syrian soil. There’s no knowing, maybe al Shara will be the best man who will get to reconcile between them. Miracles happen, even if under the nose of the best intelligence services in the world, who didn’t know and didn’t evaluate the complete collapse of the Assad regime”. “The warm Arab and international envelope tightening around Damascus”, he writes, “is ready to give him credit although it doesn’t know yet where he’s heading, assuming any leader will be better than Assad. That, by the way, is what the Syrians also believed Assad senior would be when he toppled the rule of General Salah Jedid, only to get a new mass murderer.

Right now, as the old song goes, “the future’s not ours to see …” But we might take hope from the last line of the late Robert Fisk‘s last book, The Night of Power, published posthumously earlier this year: “… all wars come to an end and that’s where history restarts”.

Author’s note

There have been many stunning pictures published to date of the Syrian revolution, but none that I’ve found as personally poignant as this one. It depicts jubilant Syrians lining the Roman archway that stands at the eastern end of Damascus’ historic Suq al Hamadiyah. When we were last in Syria, in the Spring of 2009, I photographed the arch from inside the darkened Suq (during one of the city’s frequent power cuts) , revealing the impressive remnants of the Roman Temple of Jupiter and the magnificent Omayyad Mosque, the fourth holiest place in Islam (after Mecca, Medina and Al Quds/Jerusalem).

For more on the Middle East in in That Howling Infinite, see A Middle East Miscellany:

Aleppo shock to Hama huge leap forward: triggers in Syria’s 11-day blitz that unravelled Assad

David Kilcullen, The Australian, 13th December 2024

The speed of the regime’s collapse was startling, but it should not have been. Beyond the general dynamics of government collapse, something else was happening.

The regime’s collapse accelerated dramatically after the fall of the central Syrian city of Hama on the evening of Thursday, December 5, Syria time. Picture: Emin Sansar/Anadolu via Getty Images

This was not strictly true: HTS had been biding its time in its stronghold of Idlib province, on Syria’s northwestern border with Turkey, for five years since a ceasefire brokered by Turkish and Russian negotiators in 2020, avoiding direct confrontation with the regime and building its own structure outside state control.

Its parallel government included several ministries and a civil administration, the Syrian Salvation Government, governing a population of four million, the size of Croatia or Panama. Though dominated by HTS, the SSG has been somewhat politically inclusive, and several non-HTS leaders have had key roles in its administration.

It sought to include the independent governance councils that had arisen organically during the early days of the anti-Assad rebellion, and it established local municipal managers to provide essential services across its territory.

HTS’s small combat groups operated like a fast-moving light cavalry force. Picture: Omar Haj Kadour / AFP

American analysts in 2020 assessed the SSG as technocratic, “post-jihadi”, focused on internal stability and non-ideological governance, seeking acceptance from Turkey and the US, and unlikely to become a launch pad for external attacks.

Aaron Zelin – the Western expert most familiar with HTS and the author of an important book on the organisation, The Age of Political Jihadism – has observed that despite still holding extremist beliefs, HTS acts more like a state than a jihadist group.

While the SSG was focusing on social services and economic activity, HTS commanders were investing in advanced military capabilities. Building on experience from before the 2020 ceasefire, HTS organised its forces into small combat groups of 20 to 40 fighters that could mass quickly to swarm a target using several teams, or disperse to avoid enemy airstrikes or artillery.

They were highly mobile, operating like a fast-moving light cavalry force, mounted in a mix of hard and soft-skinned vehicles that included captured armoured vehicles and armed pick-up trucks (known as technicals).

Reconnaissance teams, scouts and snipers moved in civilian cars or on motorcycles. HTS combat groups carried heavy and light weapons including rocket launchers, captured artillery pieces, mortars, recoilless rifles, anti-tank missiles and Soviet-bloc small arms seized from the government or rival resistance groups including Islamic State.

Rebel fighters stand next to the burning gravesite of Syria’s late president Hafez al-Assad at his mausoleum in the family’s ancestral village of Qardaha. Picture: Aaref Watad / AFP

HTS also used the ceasefire to professionalise itself, studying the wars in Ukraine, Gaza and Lebanon. It established a military academy to educate officers in “military art and science”, and created civil affairs units, humanitarian agencies and a specialised organisation to convince government supporters to defect.

It used drones for reconnaissance, for leaflet drops on regime-controlled areas and as one-way attack munitions to strike targets with explosive warheads. It manufactured weapons and drones, and modified technicals with additional armour. HTS leaders built intelligence networks and command-and-control systems while allegedly also forging relationships with regional intelligence services and special operations forces.

Thus, the strength of HTS was not unexpected in itself. On the other hand, the rapidity of the regime’s collapse – which accelerated dramatically after the fall of the central Syrian city of Hama on the evening of Thursday, December 5, Syria time – was startling. It probably should not have been. Governments, unlike resistance movements, are tightly coupled complex systems that rely on numerous institutions and organisations, all of which must work together for the state to function.

As Joseph Tainter showed in The Collapse of Complex Societies, once co-ordination begins to break down, these interdependent systems unravel, the collapse of each brings down the next, and the entire structure falls apart. For this reason, in a process familiar to practitioners of irregular warfare, resistance groups (which tend to be loosely structured and thus more resilient to chaos) degrade slowly under pressure – and rebound once it is relieved – whereas governments collapse quickly and irrevocably once initial cohesion is lost.

As a team led by Gordon McCormick showed in a seminal 2006 study, governments that are losing to insurgencies reach a tipping point, after which they begin to decay at an accelerating rate. The conflict then seems to speed up and the end “is typically decisive, sudden and often violent”.

This pattern was very noticeable during the fall of the Afghan republic in 2021, for example, which also occurred in an 11-day period. The final Taliban offensive captured every province but one, and took the capital, Kabul, in a series of victories between August 4 and 15, 2021. Many garrisons surrendered, fled without fighting or changed sides.

Initial rebel successes made the regime look weak, allies failed to offer support, the security forces defected and other rebel groups suddenly rose up across the country. Picture: Aaref Watad / AFP

To be sure, the Taliban’s final campaign was built on years of coalition-building and insurgent warfare. Similar to HTS, the Taliban relied on patient construction of parallel networks largely illegible to an Afghan state increasingly alienated from, and seen as illegitimate by, its own people.

It also was enabled by a stunningly shortsighted political deal with the US in 2020 and an incompetent US-led withdrawal in 2021. Even so, the collapse of the Kabul government was faster than expected, with president Ashraf Ghani fleeing by helicopter in a manner remarkably similar to Bashar al-Assad’s exit last weekend.

The fall of South Vietnam in 1975 was likewise extraordinarily rapid, occurring in just nine days after the decisive battle of Xuan Loc, with South Vietnam’s last president, Nguyen Van Thieu, fleeing for Taiwan on a military transport plane.

Similarly, Fulgencio Batista’s government in Cuba fell in only five days, between December 28, 1958 – when a rebel column under Che Guevara captured the town of Santa Clara – and the early hours of January 1, 1959, when Batista fled by aircraft to the Dominican Republic. He had announced his resignation to shocked supporters a few hours earlier at a New Year’s Eve party in Havana, starting a scramble for the airport.

In Syria’s case, beyond these general dynamics of government collapse, something else was happening: a military version of what political scientists call a “preference cascade”.

As Timur Kuran, originator of the concept, points out, under repressive regimes (or ostensibly democratic ones that censor dissent) the gap between public pronouncements and private opinions increases over time, until many individuals dissent from the approved narrative and lose faith in institutions that promote it but remain reluctant to reveal their real views. This “preference falsification” creates a deceptive impression of consensus. It can make regimes believe they have more support than they really do, while convincing dissidents they are all alone so there is no point expressing a contrary opinion.

But when an unexpected shock reduces the regime’s power to suppress dissent, people suddenly feel empowered to express their real opinions. They realise these opinions are widely shared and the false consensus evaporates. This can trigger a “preference cascade”, where individuals or institutions suddenly change sides and support for the government collapses overnight.

In particular, the moment when security forces, particularly police, refuse to fire on protesters is often decisive, as seen in the fall of the Suharto government in 1998, the overthrow of Hosni Mubarak in 2011 or the collapse of the East German regime in 1989.

Kuran’s initial work centred on the East European revolutions of 1989, which were unexpected at the time but seemed inevitable in retrospect, something Kuran later came to see as inherent in revolutionary preference cascades.

The most extreme case was the fall of Nicolae Ceausescu in Romania. During a mass rally on December 21, 1989 the dictator suddenly realised, his face on camera registering utter shock, that what he had initially perceived as shouts of support were actually calls for his downfall. When his security services refused to fire on the protesters, Ceausescu was forced to flee by helicopter. Four days later, he and his wife Elena were dead, executed after a brief military trial.

A woman poses for a photograph with a rebel fighter’s gun in Umayyad Square in Damascus. Syria’s population finally felt free to dissent from the dominant narrative. Picture: Chris McGrath/Getty Images

Syria this week was another example of a preference cascade. Initial rebel successes made the regime look weak, allies failed to offer support, the security forces defected and other rebel groups suddenly rose up across the country. Syria’s population – previously reluctant to express anti-regime sentiment for fear of repression or social ostracism – finally felt free to dissent from the dominant narrative. Assad lost control, was forced to flee, and his government collapsed. It is worth briefly recounting the sequence of events.

On November 27, the HTS offensive began with a sudden attack on Aleppo City. The outskirts of Aleppo are only 25km from the HTS stronghold in Idlib, so although the outbreak of violence was a surprise, there was little initial panic. The regime responded with airstrikes and artillery, with Russian warplanes in support.

The first major shock was the fall of Aleppo on November 30, after three days of heavy fighting. As Syria’s second largest city, scene of a bloody urban battle in 2012-16, Aleppo’s sudden collapse was a huge blow to the government. The HTS capture of Aleppo airport, east of the city, denied the regime a key airbase from which to strike the rebels, and cut the highway to northeast Syria. At this point the regime seemed capable of containing HTS, though clearly under pressure, and there was still relatively little panic.

But then on December 4, HTS attacked the city of Hama, which fell on the evening of December 5. This was a huge leap forward – Hama is 140km south of Aleppo down Syria’s main north-south M5 highway, meaning the rebel forces had covered a third of the distance to Damascus in a week. The fall of Hama was another political and psychological blow to Assad’s regime: Hama had never been under rebel control at any time since 2011.

Syrian rebel fighters at the town of Homs, 40km south of Hama, a critically important junction controlling the M5 and the east-west M1 highway that links Damascus and central Syria to the coast, and dominating Syria’s heavily populated central breadbasket. Picture: Aaref Watad / AFP

The collapse at Hama – and the perception of regime weakness this created – triggered a preference cascade. Immediately, commanders began negotiating with or surrendering to the rebels or evacuating their positions. Also, after Hama’s fall, Iranian forces negotiated safe passage and began withdrawing from Syria, denying the government one of its key allies, further weakening Assad’s credibility, and encouraging yet more supporters to defect.

The regime’s other main ally, Russia, had already retreated to its bases at Khmeimim and Tartous, on Syria’s Mediterranean coast, after losing large amounts of military equipment and a still-unknown number of casualties. The same day, Hezbollah declined to offer material assistance to the Syrian government, given that it was still under Israeli pressure and had taken significant damage in 66 days of conflict.

The town of Homs lay 40km south of Hama – not much closer to Damascus but a critically important junction controlling the M5 and the east-west M1 highway that links Damascus and central Syria to the coast, and dominating Syria’s heavily populated central breadbasket. By early Friday, December 6, HTS combat groups were massing to assault Homs, but the city’s defences collapsed and it fell without a significant fight. By this point, security forces were dispersing, some retreating to Damascus but many fleeing to coastal areas.

The fall of Hama and Homs in quick succession encouraged other rebel groups to pile on, with several now mounting their own offensives against the regime. Uprisings broke out in the southern cities of Daraa and As-Suwayda on Friday and Saturday, December 6 and 7. These were less of a shock than the loss of Hama – Daraa was, after all, the cradle of the revolution in 2011 – but given everything else that was happening, the government simply lacked the forces to suppress them.

Simultaneously, US-backed forces in the far south advanced north from their base at al-Tanf, near the Jordanian border, while US-allied Kurdish troops of the Syrian Democratic Forces attacked in the east, crossing the Euphrates and seizing regime-controlled territory near Deir Ezzour. American aircraft flew airstrikes to support the SDF, which also seized the border post at Bou Kamal, blocking access to Iraqi militias that had been crossing into Syria to support the regime.

By Sunday, the regime had collapsed and the rebels occupied Damascus without a fight. Picture: Louai Beshara / AFP

By this point – last Saturday evening, December 7, Syria time – the government was on its last legs. That night an uprising broke out in Damascus, launched by civilian resistance groups and disaffected military units keen to distance themselves from the regime as the rebels closed in. Government troops began abandoning their posts, changing into civilian clothes, ditching their equipment and disappearing into the night. Large numbers of armoured vehicles, including T-72 tanks, were abandoned in the streets of the capital. Assad had planned to address the nation that evening but did not appear.

Later that night, apparently without asking Assad, the high command of the Syrian armed forces issued an order to all remaining troops to lay down their weapons and disperse. Assad fled about 2am on Sunday, flying out in a Russian transport aircraft. Assad’s prime minister, Mohammed al-Jalali, announced that he was willing to act as caretaker during transition to a provisional government, showing that Syria’s civil government, like the regime’s military forces, had collapsed. Despite initial reports that Assad’s aircraft had been denied entry into Lebanese airspace then shot down over Homs, Russian media reported later on Sunday that he had arrived in Moscow.

By Sunday, the regime had completely collapsed and the rebels, led by HTS commander Ahmed al-Sharaa, formerly known as Abu Mohammed al-Jolani, occupied Damascus without a fight.

The same day, US aircraft mounted dozens of airstrikes across the country, targeting Islamic State or regime forces, while Israeli troops crossed the Golan Heights buffer zone and began advancing towards Damascus. By Monday, despite initially claiming their incursion was limited and temporary, Israeli forces were 25km from Damascus, Israeli politicians had announced the permanent annexation of the Golan, and Israeli aircraft were striking Syrian military bases and sinking Syrian ships at the Latakia naval base.

The SDF has seized a chunk of eastern Syria, other US-allied rebel groups hold key parts of the south, and Islamic State still has numerous supporters and active cells in the country. Russia still controls its two Syrian bases, while Syria’s ethnic and religious minorities including Christians and Alawites are deeply anxious about the future, despite promises of tolerance from HTS.

Given the speed and totality of Assad’s collapse, some observers seem to be assuming that HTS will now, by default, become the dominant player in Syria. On its face, this may seem a reasonable assumption, given what happened in similar situations – Havana 1959, Saigon 1975, Kabul 2021 and so on.

But it would be premature in Syria’s case since the war is very much ongoing. As the northern hemisphere winter closes in and Western allies prepare for a change of administration in Washington, Syria – along with Gaza, Lebanon, the Red Sea, Ukraine, Taiwan and the Korean peninsula – will remain a major flashpoint into the new year.

David Kilcullen served in the Australian Army from 1985 to 2007 and was a senior counter-insurgency adviser to General David Petraeus in 2007 and 2008, when he helped design and monitor the Iraq War troop surge.

The Most Courted Leader in the Middle East Still Has No State

Arab and European heads of state are lining up to meet Ahmed A-Shara, the leader of the Syrian rebel organizations that ousted Assad, who has returned to his original name and is no longer calling himself al-Golani

Qatar isn’t alone. In the race to the presidential palace in Damascus the Turkish Foreign Minister Hakan Fidan came first to shake A-Shara’s hand. The foreign ministers of other Arab states, such as Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE are preparing to land in Damascus in the coming days to personally congratulate the leader of the sister state.

- The wicked witch is dead, but will Syria return to life?

- Syria’s fragile hope is being battered by Israel’s predatory campaign of destruction

- Syrian liberal circles are wary of the religious leadership, despite widespread optimism

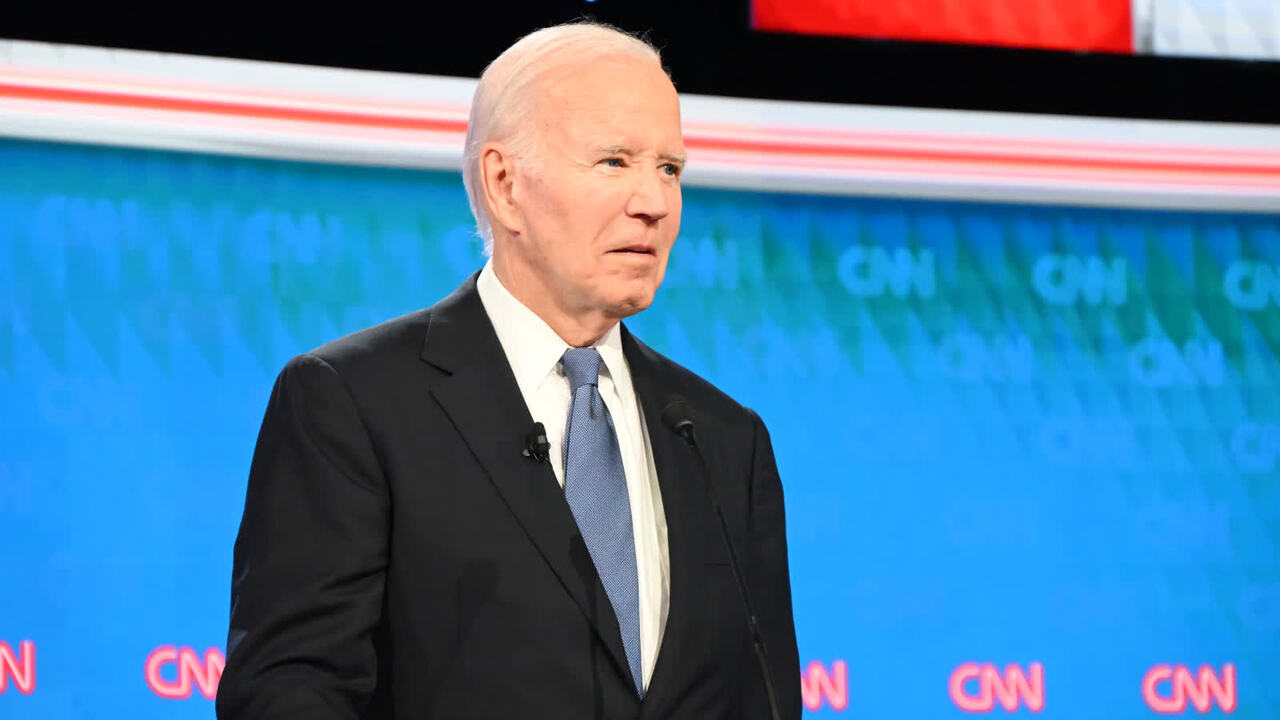

At the same time Biden’s administration is examining the possibility of removing A-Shara and his group from the terrorists’ list while European leaders, headed by Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni, who only two weeks ago spoke of the possibility to normalize their relations with the Assad regime, are already trying to coordinate meetings with the new regime’s leadership.

Once as partners when they helped Azerbaijan in its war against Armenia and once as enemies in the Gaza front or now on Syrian soil. There’s no knowing, maybe A-Shara will be the best man who will get to reconcile between them. Miracles happen, even if under the nose of the best intelligence services in the world, who didn’t know and didn’t evaluate the complete collapse of the Assad regime.

The warm Arab and international envelope tightening around Damascus is ready to give him credit although it doesn’t know yet where he’s heading, assuming any leader will be better than Assad. That, by the way, is what the Syrians also believed Assad senior would be when he toppled the rule of General Salah Jedid, only to get a new mass murderer.

But it’s not clear yet under what terms. Will they want to preserve their provinces’ autonomy, and will the Syrian regime agree, when Turkey operates its military and economic leverages. Will the Kurds even have a bargaining chip left when Trump enters the White House? Trump tried already in 2019 to withdraw U.S. forces from Syria and was blocked by internal and external pressure. Now he may implement his wish with his ally Recep Erdogan.