Firstly, it’s been there for eons, it’s cliffs of chalk and dolomite keeping a lonely watch over the Judean Desert, the Great Rift Valley with the Dead Sea 400 meters below in its deep, and the limestone plateau of Moab beyond.

Secondly, Herod the Great (37-4BCE) built a palace atop its mesa-like summit (see my King Herod’s edifice complex), and during the great Judean Revolt against Rome which ended in 71CE with the destruction of Jerusalem, it was occupied and fortified by sicarii rebels (named so for their knives, their weapon of choice) and their families.

Third, it’s one of Israel’s most popular tourist attractions.

Fourth, it was a terrible, interminable film. The aging Peter O’Toole could only have done it for the dosh, though all those Judean landscapes are cinematic heaven – the Judean Desert is one of the most beautiful vistas in the world.

And fifthly, and most importantly, Masada is intrinsic to the state of Israel’s national story and its Identity. It was the site of a very famous last stand – like Thermopylae, the Alamo, Gandamak, Little Big Horn, and Isandlwana were famous last stands. An heroic, to the very ‘last man’ of the few against an overwhelmingly, most often ‘savage’ many. But this one raises a finger of defiance at all who threaten the tiny but nuclear state: Never again shall Masada fall!

Masada has long been a favourite place of pilgrimage site for Jewish youth groups, and for years the IDF has held induction ceremonies there. These ceremonies are now also held at various other memorable locations, including the Armoured Corps Memorial at Latrun, the Western Wall and Ammunition Hill in Jerusalem, Akko Prison, and training bases. It was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2001.

But there’s a sixth thing about Masada, or more accurately a 5.2 – the historical truth of the story is open to conjecture.

The popular narrative of what happened long ago in the Spring of 74 CE is that a tiny band of men, women and children, having held out against for two years on a barren mountain top defying the might of the greatest military power the antique world has known, and chose to self-slaughter rather than endure the indignity of execution or captivity.

The only historical account of the siege was written after the event by the Jewish scholar Flavius Josephus who allegedly interviewed a couple of the survivors who has managed to escape before the end.

Josephus was a high born, well-educated rebel leader who had surrendered to the Romans before the siege of Jerusalem. Apparently, he impressed Vespasian, the Roman general but predicting he’d become emperor, and thence acted as his advisor on Jewish affairs. Vespasian did indeed become emperor, so Josephus’ star must’ve shone even brighter, and he served Vespasian’s son Titus when the latter took command of the forces in Judea on his father’s accession and conquered and destroyed Jerusalem in 70CE.

Nowadays, historians and archaeologists are reconsidering the facts of the siege and the suicides, and whilst not arguing outright that Josephus fabricated the story, suggest he may have embellished it. Most interested parties, including our guide Shmuel, have their own interpretation – the archeological evidence is ambiguous at best and is entirely rejected by some scholars. Some believe the holdout and the siege were not that significant by The Romans’ reckoning – they certainly took their time doing something about it two years afterwards in fact. But a sideshow in a successfully concluded war. Others argue that the mass-suicide did not occur and that the rebels and their families were simply massacred. A selection of articles regarding the many theories about Masada are republished below.

As the journalist exclaims at the end of The Man Who Shot Liberty Valence, why let the truth get in the way of a good story?

Climbing Masada

I wrote in my Travel diary for Thursday, 12 July 1971: “A desert ride, traveling the length of the Dead Sea to the mountain fortress of King Herod with a a host of American Jews. It was high summer, and the sun was at its height. The climb was a 35-minute agony but oh, the panorama! And it was heaven to collapse atop as tourists stepped over me on their way to the cable car (at a pound a return trip, way too much for my budget). The summit was an empty ruin of reconstruction, but it must’ve been impressive, and view from below must’ve given the Romans the shits. I came, saw and descended. The return journey to Jerusalem via the Ein Gedi oasis and a Dead Sea resort was a bad trip dominated by those American Jews”.

I visited Masada again in May 2014 with my wife Adèle – and we decided we’d watch the sunrise from its crest. So, there we were in the car park, five o’clock in the morning, in the deep dark with fellow travelers a third our age. And we were off! at a brisk pace up the zig zag track. It was better maintained since my prior trek, but torturous, nonetheless. Up up and up as the lightening day at our backs reminded us that the clock was tick tick ticking and that any delay or mishap would render our mission pointless. I can’t say whether this climb was any better or worse than my first – but this time, I was much fitter, even at my age, and it was not in the middle of the day in high summer.

And then, there we were – in good time to catch our breath and settle in at a good vantage point as the horizon glowed and old sol peeked bit by bit above the blackness of the Moab wilderness in the east, casting his good day sunshine rays on the glistening Dead Sea over a thousand feet below. It was a glorious feeling – the sense of achievement we felt that we were fit enough to keep pace with the young folk, and the beauty of the view. To our left, a pair of lovely Israeli girls began to sing a joyous Hebrew song. On our right, a gaggle of German Pentecostals were led in prayer by their pastor. Hosanna in excelsis!

And then, it was all over. The daylight revealed the remains of Herod’s palace and the zealot rebels’ village spread out behind us, and the rock-fill ramp the Romans constructed to take Masada by storm. A too-short reconnoiter and it was time to head back to join our bus. We’d looked forward to taking the easy way down, by cable car. But that didn’t start running until nine o’clock; it was seven o’clock and our bus left in less than an hour. So off we went …

Our return journey to Jerusalem was much like my first – a refreshment stop at the oasis of Ein Gedi (and a brief stroll through the scenic national park in the wadi – which hadn’t been established in 1971) and a two-hour stopover at a sad venerate of a resort on the diminishing Dead Sea so our companions could wallow in the mud. We chose to sit at a deserted bar like a couple of Tom Waits’ mates with a couple of glasses of local vino blanco. The resort itself appeared to be designed for Russian tourists, as was demonstrated by the arrival of a bus load of babushkas led by a black-robed and bearded orthodox priest. To borrow from Leonard, I have seen the future baby, and it mundane!

© Paul Hemphill 2024. All rights reserved.

See also in In That Howling Infinite: A Middle East Miscellany

A selection of my photos of Masada:

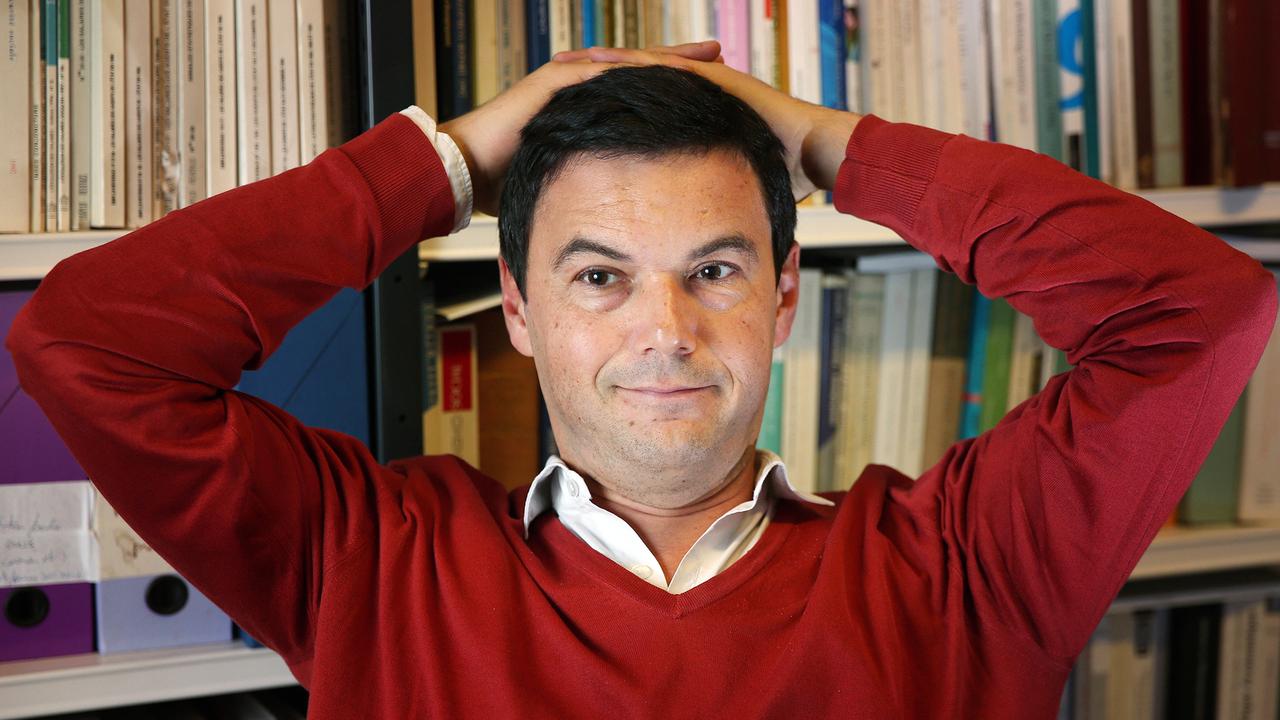

The author on the rampart

Reconstruction in progress

Israel’s Masada myth: doubts cast over ancient symbol of heroism and sacrifice

Herod the Great’s fortified complex at Masada was a winter retreat but also an insurance against a feared rebellion of his Jewish subjects or an attack from Rome. Luxurious palaces, barracks, well-stocked storerooms, bathhouses, water cisterns sat on a plateau 400m above the Dead Sea and desert floor. Herod’s personal quarters in the Northern Palace contained lavish mosaics and frescoes.

But by the time the Jews revolted against the Romans, Herod had been dead for seven decades. After the temple in Jerusalem was destroyed, the surviving rebels fled to Masada, under the command of Eleazer Ben Yair. Around 960 men, women and children holed up in the desert fortress as 8,000 Roman legionnaires laid siege from below.

Using Jewish slave labour, the Romans built a gigantic ramp with which they could reach the fortress and capture the rebels. On 15 April in the year 73CE, Ben Yair gathered his people and told them the time had come to “prefer death before slavery”. Using a lottery system, the men killed their wives and children, then each other, until the last survivor killed himself, according to historian Flavius Josephus’s account.

After the declaration of the state of Israel in 1948, Masada took on a new significance, symbolising heroism and sacrifice. “It is a place of ancient doom which time has turned into a symbol of the pride of a new nation,” wrote Ronald Harker in the Observer book on Masada, published in 1966.

Newly enlisted soldiers were taken to the desert fortress to swear their oath of allegiance, including the shout: “Masada will not fall again!”

But some have cast doubt on the “myth of Masada”, saying it was either exaggerated or the suicide story was simply wrong.

Guy Stiebel, professor of archaeology at Jerusalem’s Hebrew University and Masada expert, said the evolution of myth is common in young nations or societies. “In Israel it’s very typical to speak in terms of black and white, but looking at Masada I see a spectrum of grey.

The left regard Masada as a symbol of the destructive potential of nationalism. The right regard the people of Masada as heroes of our nation. For me, both are wrong.

“If you put me in a corner and ask do you think they committed suicide, I will say yes. But this was not a symbolic act, it was a typical thing to do back then. Their state of mind was utterly different to ours.

“The myth evolved. All the ingredients were there. At the end of the day, it’s an excellent story and setting, you can’t ask for more.”

Yadin Roman, the editor of Eretz magazine, who is compiling a commemorative book on the Masada excavation, said some archaeologists had posited alternative theories, involving escape, although in the absence of evidence many were now returning to the suicide theory.

“Masada became an Israeli myth,” he said. For a nation still reeling from the revelations of the 1961 trial of Adolf Eichmann, “brave Jewish warriors standing up to the might of the Roman army was a much-needed antidote. But some people challenged the merits of the story – you stand alone on a hill to fight your enemies and then commit suicide? This is the ‘Masada complex’? This is the model for Israel?”

David Stacey, a veteran of the excavation 50 years ago, dismissed the story of mass suicide. “It was completely made up, there was no evidence for it,” he said. “Did Yadin pursue this story because he was an ardent nationalist, or because he needed to raise money for his excavation? Yadin was a smart enough operator to know that to succeed, you’ve got to sell a story. He succeeded.”

Masada: From Jewish Revolt to Modern Myth

Jodi Magness. Princeton: Princeton University Press 2019.

“A dream of ages has come true: Masada has been excavated and reconstructed.” So wrote Yigael Yadin of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem in a tourist pamphlet about Masada published in November 1965. Yadin extolled remarkable finds, including “tens of miles of walls; 4000 coins,” and more than 700 inscribed ostraka, which he and his team recovered from the Herodian palace-fortress of Masada during 11 months of excavations between 1963 and 1965. To some scholars in the 21st century, however, the exultant tone of Yadin’s expression (in both the pamphlet and his popular book, Masada: Herod’s Fortress and the Zealots’ Last Stand, Random House 1966) betrayed a political agenda that complicated both his professional legacy and that of the site. In Masada: From Jewish Revolt to Modern Myth, however, Jodi Magness reclaims both the remains of Masada and the work of its famed excavator Yadin by reframing, and thus transforming, the narratives about each. Rather than merely summarizing the results of excavations or associated scholarship, Magness’ treatment does something novel: it constitutes a multidimensional work that uses Masada as “a lens through which to explore the history of Judea” (3) from the middle of the second century BCE through the first century CE.

The renown of Masada, of course, predates Magness’ treatment and more recent explorations of the site. Part of its fame owes to the remarkable geographic position of the elaborate palace-fortress, constructed by Herod, which looms over an extreme and desiccated landscape beside the Dead Sea. Yet Josephus, who composed his Jewish War in Rome under Flavian patronage, is credited for immortalizing this fortress and the demise of the Jewish rebels who had retreated there. Indeed, the soliloquy Josephus attributes to a certain Eleazar Ben-Yair dramatically concludes his account of the Jewish revolt against Rome (66–73 CE). Fully aware that the Romans had encircled their holdout and that the remainder of Judea had already fallen into Roman hands, Ben-Yair exhorts his compatriots in their final hour “not [to] disgrace ourselves. . . . Let us not . . . deliberately accept the irreparable penalties awaiting us if we are to fall alive into Roman hands” (Joseph., BJ 7.553–65; Loeb transl.). Ben-Yair proposes, instead, to enact a mass suicide whereby he and his peers would take their own lives immediately after those of their surviving wives and children (“Let our wives thus die dishonored, our children unacquainted with slavery,” BJ 7.335). Magness begins her preface with Ben-Yair’s words, but then, unexpectedly, challenges the plausibility of the associated account; she introduces readers to why stories in Josephus such as this one are of suspect historicity. In discussing the remains of Roman camps and siege works at Masada, including those she excavated herself, Magness demonstrates why answers to questions about the last days of Masada are best sought through archaeology, outside of Josephus’ narrative (ch. 1). This is so, despite the renown of Josephus’ writings on the topic, which lured generations of explorers and archaeologists to risk their lives in search of the original site where Ben-Yair and his peers purportedly chose death over surrender (ch. 2).

In subsequent chapters, Magness takes a panoramic view, contextualizing Masada in its natural, architectural, political, and historical settings. “Masada in Context” (ch. 3) manifests how harsh, inaccessible, and challenging for human habitation were the landscapes surrounding and including Masada, even if, under periods of Hasmonean control of Judea, rulers systematically constructed fortresses in comparable locations (e.g., Hyrcania, Machaerus, Callirhoe). Whether the Hasmoneans originally built on Masada remains debatable, but Magness’ summary of Herod’s local construction illustrates how elaborate his northern palace was, with a service quarter, synagogue, western palace quarter (which included a bathhouse and rooms with elaborate mosaic decoration), and southern portion, which included water installations and cisterns that Yadin once estimated could hold 1,400,000 cubic feet of water (69; cf. BJ 7.290–91). But while Masada might have reflected multiple feats of engineering, particularly given its topography and climate, Magness notes that it was merely one component of Herod’s legendary building program, which entailed extensive construction in Jerusalem (including Herod’s palace, the western hill, Temple Mount, and Antonia fortress), Caesaria Maritima (a man-made harbor, pagan temples, and aqueducts), as well as Samaria-Sebaste, Jericho, and Herodium (ch. 4). “Judea Before Herod” (ch. 5) and “From Herod to the First Jewish Revolt Against Rome” (ch. 6) collectively offer a valuable historiography of the region, emphasizing the social, political, economic, and religious unrest that ultimately impelled the revolt in 66 CE. Magness chronicles how Judea grew increasingly fractious, following internal divisions between “sects” of Pharisees, Essenes, Sadducees, and Jesus followers; political machinations of the Hasmoneans; and intersections between local and regional geopolitics. These last included Parthian invasions; the ascendancy and reign of Herod; the division of Herod’s kingdom among his three sons; and the subsequent imposition of a series of Roman governors, including procurators Lucceius Albinus in 62–64 CE and Gessius Florus in 64–66. By 66, Judea had indeed become a “tinderbox about to go up in flames” (141). Jewish rebellions in Caesaria Maritima followed provocations of non-Jewish residents; revolt spread to Jerusalem and ultimately precipitated the Roman destruction of the Jerusalem Temple. Yet, as Magness details, Jewish rebellions against Rome also spread outside urban centers; Herod’s old fortresses in Machaerus and Masada became sites of refuge for ragtag groups of rebels and refugees, brigands, and those identified as the Sicarii (164–65), as well as women and children.

In “The Rebel Occupation of Masada (66–73/74 CE)” Magness resumes her direct consideration of the site (ch. 8). This chapter offers a significant payoff: its evaluation of the stratigraphy and quality of finds at Masada yields a gripping analysis of the rebels’ last days in the fortress. Magness’ interpretations of distributions of cooking pots, ovens (tabuns),utensils, domestic objects, and cosmetic items, as well as hair nets, louse-ridden combs, plaited human hair, and remains of olives, fish, dough, dried figs, nuts, and pomegranates, recreate the tenor of daily life for those who had taken over Herod’s fortress. This analysis reflects the strengths of her previous work, Stone and Dung, Oil and Spit: Jewish Daily Life in the Time of Jesus (Eerdmans 2011). It is in fact the very abundance of food and daily supplies found on Masada that prompts Magness to suggest that “Josephus’s account of the mass suicide” (BJ 7.336), which had also detailed the rebels’ preliminary destruction of their means of subsistence, “is all or partly fabricated” (170). In chapter 9 (“‘Masada Shall Not Fall Again’: Yigael Yadin, the Mass Suicide, and the Masada Myth”), Magness continues to reassess aspects of the excavation and reception history of Masada in the 20th and 21st centuries.

Among the most satisfying portions of the book are its final chapters, where the work of preceding sections comes to fruition in revealing why Masada fell as it likely did. These are also the places where Magness fully enters the narrative, describing her own role in the history of the site. For instance, while she chronicles the life and excavations of Yadin, as well as his professional career in archaeology and Israeli politics; she also situates her personal experience studying with him as an 18-year-old student at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Indeed, she declares that Yadin was “. . . the most mesmerizing speaker I have ever heard” (190). After briefly engaging with the work of scholars who have critiqued Yadin’s interpretations of data, including Nahman Ben-Yehuda (The Masada Myth: Collective Memory and Mythmaking in Israel, University of Wisconsin Press 1995), Magness consolidates her appreciation for Yadin’s methods and cautiousness as an archaeologist, particularly following her own excavation of the Roman military camp. The epilogue also plays a significant role in concluding the book, where Magness rewards readers by giving them directions for her favorite route to tour Masada, detailing how and where to ascend the site, in which order to view its remains, and where to gaze. She thereby invites readers, as future tourists, to enter the same spatial continuum as Herod, ancient rebels, explorers, and archaeologists, who once occupied the same ground under wildly discrepant circumstances and conditions.

Few would be better suited to produce a work such as this one. Magness herself studied with Yadin; she co-published the military equipment from his excavations and, in 1995, excavated the assault ramp and Camp F at Masada alongside Gideon Foerster, Haim Goldfus, and Benny Arubas. As Yadin never completely published his teams’ discoveries from Masada (he produced only one report, The Excavation of Masada 1963/4: Preliminary Report, Israel Exploration Society 1965, and popular assessments in Hebrew and English in 1966), various archaeologists and specialists, including Ehud Netzer and Magness, published the findings from his original excavations in eight volumes after his death (Masada: The Yigael Yadin Excavations 1963–1965 Final Reports, Israel Exploration Society and Hebrew University of Jerusalem 1984–2007). Amnon Ben-Tor subsequently synthesized these reports, making their contents accessible to the “educated and inquisitive layperson” (Back to Masada, Israel Exploration Society 2009, quote from p. 2). Magness’ project expands on these preceding works, as she redefines the story of Masada by vivifying its historical age as much as the state of its remains. She is also a rare field archaeologist skilled in transforming technical findings into riveting and thoroughly readable historiography, thereby successfully filling a lacuna in existing literature about the period; her account meaningfully integrates literary and archaeological evidence and scholarship in ways that differently benefit researchers, undergraduate students in archaeology and ancient history, and an interested public. Her Masada is a distinctive one, revealing why Masada has mattered to so many people throughout history and continues to do so today.

Karen B. Stern

Department of History, Brooklyn College of the City University of New York

Did the Jews Kill Themselves at Masada Rather Than Fall Into Roman Hands?

The tradition of mass suicide at the ancient desert fortress as described by Josephus has little archaeological support

“Since we long ago resolved never to be servants to the Romans, nor to any other than to God Himself, Who alone is the true and just Lord of mankind, the time is now come that obliges us to make that resolution true in practice … We were the very first that revolted, and we are the last to fight against them; and I cannot but esteem it as a favor that God has granted us, that it is still in our power to die bravely, and in a state of freedom.” Elazar ben Yair, leader of the Sicarii rebels

A servant of the American people, the new U.S. president, Donald Trump, will be visiting Israel next week on his very first foreign tour. Among the rumored stops on his brief trip – later debunked – was Masada, icon of Jewish resistance. But is the story behind Masada and the suicide of the Jews cornered there, rather than capitulate to Roman hegemony, fake news?

Every schoolchild in Israel knows the story of how Jewish heroes revolted against the pagan Romans, holed up in the desert fortress of Masada – and opted for mass suicide, killing themselves and their families, over capture and humiliation by Emperor Vespasian’s forces.

The story of the Siege of Masada was brought down the ages thanks to Joseph ben Matityahu, a.k.a. Flavius Josephus, once a commander in the Great Jewish Revolt that began in 67 C.E. who turned coat and became an advisor to Vespasian. He told of the defenders led by Elazar ben Yair and their decision to die rather than be taken.

Josephus’ account in “The Wars of the Jews” states that there were 967 people at the fortress of Masada. They had been waging a guerrilla campaign against the Romans, the historian recounted, but in 73 C.E., with the war all but won by the Romans, Flavius Silva and his legions arrived to complete the victory.

Born free, die free

The late general and archaeologist Yigael Yadin, who led the 1963 excavations of the fortress built by King Herod, felt that the archaeological evidence supported Josephus’ account. However, despite the general acceptance of this account among Israelis as fact, scholars do not all agree.

The truth is that Yadin’s excavations yielded little archaeological material to corroborate, or negate, the account of the siege laid out by Josephus. The finds remain open to interpretation. And the fact is that Josephhus’ account remains the only one of the events on the windswept desert plateau by the Dead Sea.

The walls of the Masada fortress, built by King Herod, once bore frescoes.Credit: Ilan Assayag

What wasn’t there

The excavators under Yadin were disappointed by how little they found to confirm Josephus’ account, admits Professor Nachman Ben-Yehuda, professor at Hebrew University in Jerusalem. He for one feels that Yadin modified his conclusions to support Josephus’ version in his own book “The Masada Myth: Collective Memory and Mythmaking in Israel” (1995).

Among the items that Yadin found at Masada were scrolls, pottery, clothes, including a sandal, weapons that include arrow heads of indeterminate origin and slingshot stones, and Jewish coins that date up to the year of the siege, proving human occupation at the time. However, what these items do not prove, is what happened at Masada in 73 C.E.

Haim Goldfus, professor at Ben Gurion University of the Negev, has long cast doubt on the existence of a siege. In fact he suspects there was no war there at all. “There is no evidence at all at the site of blood being spilled in battle,” Goldfus told Haaretz in the past.

Any tour guide worth his salt immediately points at the battery, otherwise known as the “Roman ramp,” which the Roman soldiers were supposed to have used to position a battering ram to break through the fortress’ massive stone walls.

Nonsense, say some scholars. “It couldn’t have fulfilled the role attributed to it in breaking through the wall, because it was too narrow and small and couldn’t have been used by the Roman army to position a battering ram. In light of the finds in the area where the [Romans] broke through, we understood that nothing happened there,” Goldfus says.

Other scholars argue in favor of tradition. Jonathon Roth of San Jose State University in California believes that a siege did take place, and that due to the height of the rock spur the Romans used as a foundation for their construction, they would have been able to construct their ramp in as little as four to six weeks. The siege would have been over shortly after that, Roth feels.

Though the first interpretation is tempting, unfortunately, no one can say for certain.

The missing dead

Despite Josephus’ account that 967 people called the fortress of Masada home in their final day, only 28 bodies were discovered by excavators, and only three were found in the palace, where Josephus said all were killed.

While wild animals, scavengers, and weather could explain why more intact bodies have not been found, thus far there have been no signs of any other bodies.

The missing bodies cast further doubt on Josephus’ account. It raises the possibility that Professor Jerome Murphy-O’Conner, from Ecole Biblique, was correct: there was no mass suicide at Masada.

Professor Yadin thought the remains had to be of Masada’s defenders and that the three found together were a family, perhaps the last defender who killed his men and his family and then finally killed himself. Yadin based his interpretation on the remains of armor found nearby, as Richard Monastersky wrote in 2002.

However, an anthropologist on the excavation team estimated that the man was between 20 and 22 years old, the woman was between 17 and 18, and the child was 11 or 12. While the man and woman could have been a married couple, the child could not have been theirs.

The other 25 bodies were found in a cave, which isn’t mentioned in Josephus’ account, while the bodies he did mention just aren’t there.

Shay Cohen, professor of Hebrew literature and philosophy at Harvard University, suspects these remains were indeed of Jews hiding from the Romans, but not well enough, and they were killed.

If so, that would contradict the account that the defenders of Masada were willingly killed by their own people to avoid capture by the Romans.

Joseph Zias of Jerusalem’s Rockefeller Museum suggests another possibility. He believes that the remains could be those of Roman soldiers. This would fit with Yadin’s admission that he had found the bones of pigs with the remains.

Dwelling with the swine would have been taboo for the Jewish rebels. However, Zias says, the Romans had no such constraints and also sacrificed pigs during burials.

The Legion Tenth Fretensis, who conducted the siege, even had a boar as one of their emblems, Zias says

Fourteen of the skeletons found in the cave were adult males. Six of them were between the ages of 35-50 and had builds that were of a “distinctly different physical type from the rest,” Prof. Ben Yehuda told Monastersky. That begs the thought that some of the bodies belonged to Romans soldiers, who may have been killed during a fight for the fortress, or may have been part of the occupation force left behind after the siege.

Unfortunately, the question of what happened to the remaining defenders is still unanswered. And if some of the few bodies belonged to Romans, killed in fighting for the fortress of Masada or otherwise, the story of a mass suicide becomes more questionable.

3 Comments