When our gallant Norman foes

Made our merry land their own,

And the Saxons from the Conqueror were flying,

At his bidding it arose in its panoply of stone,

A sentinel unliving and undying.

Insensible, I trow, as a sentinel should be,

Though a queen to save her head should come a-suing,

There’s a legend on its brow that is eloquent to me,

And it tells of duty done and duty doing.

The screw may twist and the rack may turn,

And men may bleed and men may burn,

O’er London town and its golden hoard

I keep my silent watch and ward!

WS Gilbert and Arthur Sullivan, The Yeomen of the Guard

I read British historian David Fry’s informative Walls: a history of civilisation in blood and brick a few years ago.

We’re not talking here of idioms, metaphors and analogies, like “facing the wall”, “up against the wall”, “another brick in the wall” and the anodyne “blank wall”. It’s all about imposing and impressive, massive and deliberately built structures designed to protect, contain or separate.

The breaching of Israel’s formidable high-tech wall which ostensibly sealed off the Palestinian enclave of Gaza on October 7th 2023 (more on that later) brought me back to my earlier notes. I’d gathered a few excellent reviews and random thoughts thereon, and I resolved to complete this article. The reviews republished below are informative and comprehensive, and well-worth reading.

I offer my own thought on the subject by way of an introduction. Neither they or I mention of a certain iconic song by Pink Floyd (I “almost mentioned the war” above) but I couldn’t resist opening with what many would call “the wall of walls”. It’s not Hadrian’s Wall, which has fascinated me since our first visit in 2015, when we stood atop the windswept knoll that is Housesteads Roman Fort on a freezing May morning. Nor is the Great Wall of China, iconic and impressive as it is – though I’m sure that if it had existed, you’d’ve been able to see this too from space. By the way, the opening quotation is a paean to the Tower of London, which, “if walls could talk” would have a great tale to tell.

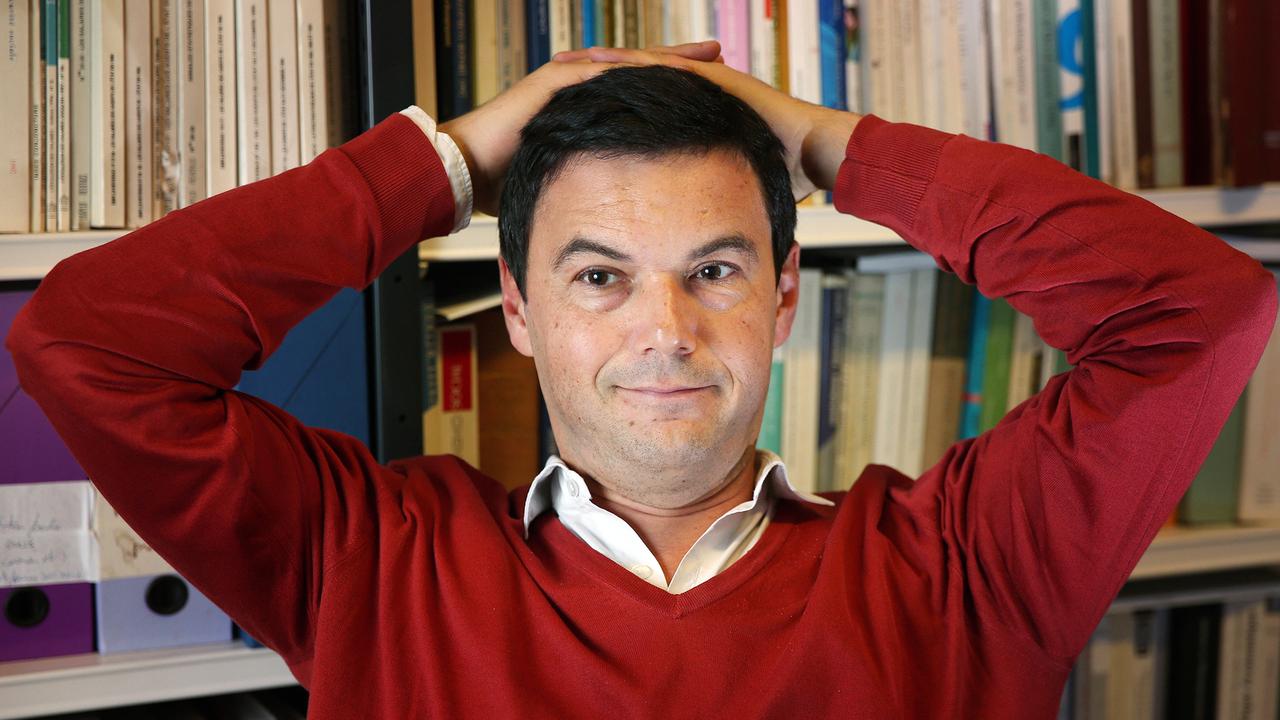

The author at Housesteads Fort on Hadrian’s Wall

…

The view from Housesteads Fort, Hadrian’s Wal

The Wall has stood through it all …

I am the watcher on the wall. I am the shield that guards the realms of men. I pledge my life and honor to the Night’s Watch, for this night and all the nights to come.

The Oath of The Night’s Watch, Game of Thrones

George RR Martin, the author of the Game of Thrones epic has said that his Ice Wall separating the northern wintry waste with its nomads and its demons from the settled and temperate Westeros with its castles and cities, its palaces and slums, and destitute and the depraved, was inspired by a visit to Hadrian’s Wall – only he built it much longer and much, much higher. “We walked along the top of the wall just as the sun was going down. It was the fall. I stood there and looked out over the hills of Scotland and wondered what it would be like to be a Roman centurion … covered in furs and not knowing what would be coming out of the north at you” However, the author adds thats: Hadrian’s Wall is impressive, but it’s not really tall. A good ladder would be all you need to scramble right on over it. When you’re doing fantasy, it has to be bigger than in real life”.

We built a wall once …

A big one. Separating the backyard of our house from Camden Street, Newtown, Sydney. It was well over six foot high, rendered and scored to look “authentic” and entered thought a gate set into an ornate arch moulded to replicate the century-old portico of our front door. To build a wall that high, we had to take Council to the Land and Environment Court. We left that house over two decades ago. Our old house has changed hands several times since, but when the present owners wanted to redevelop the back end of that one-time corner shop that we once called home, Council mandated that the wall and the gateway had to be preserved because it was “heritage”. Such is the power and presence of walls.

Which brings us to the punchline. We built the wall for privacy and for security. But one night, while we were socialising upstairs, person or persons unknown scaled our wall, entered our house and swiped the handbags on the kitchen table. When the police came to investigate, a very agile constable shimmied up the wall and sat atop. So much for our wall. We ought to have laid broken glass or razor wire!

And that is the thing about walls:

Walls work … until they don’t

We know that the Ice Wall protected by those Watchers of our opening quote fell to the zombie ice dragon Viserion and the dead. Drogon, the last of Queen Daenerys Targaryen’s “children” shattered the walls of Kings Landing, the decadent yet depressing capital of Westeros, and incinerated its unfortunate townsfolk.

The dead watch Visarion do his thing

Hadrian’s Wall fell into disrepair – it was always permeable, and in time, had served its purpose – which was perhaps as much about public relations as protection. Archeologist Terri Madenholme wrote in Haaretz: “Despite itself having a culture of violence, Rome aimed to project an image of a nation of the civilized, and what better way than having it monumentalized in stone? When Hadrian set to build the 73-miles-long wall drawing the border between Roman Britannia and the unconquered Caledonia, the message became even more clear: this is us, and that’s them. Hadrian’s Wall was much more than just a border control, keeping the Scots in check: it was a monument to Roman supremacy, an attempt to separate the civilized world from the savages”.

“He set out for Britain”, Hadrian’s historian tells us, “and there he put right many abuses and was the first to build a wall 80 miles long [Roman miles] to separate the barbarians and the Romans.

The Great Wall of China has in many places withstood the ravages of time, which says something about the skills of the workers who built it and the quality of its brickage. It had only been breached by Genghis Khan and the Manchus – until August 24 2023 when two Chinese construction workers in Shanxi province, were looking for a shortcut and drove heavy machinery through it, causing what authorities described as “irreversible damage” when they used an excavator to widen a gap in the wall.

The hole in the wall

The famous Theodosian Walls protected Constantinople since the foundation of the new capital of the Roman Empire by Emperor Constantine in 324 until they were breached by the Ottoman sultan Mehmet the Conqueror in 1453. He’d brought along a huge army and a bloody big gun. [The event is imaginatively recreated in Cloud Cuckoo Land the 2021 novel by Pulitzer prize-winning author Anthony Doerr] Istanbul remained the capital of then Ottoman Empire for over half a millennium, and though dilapidated and discontinuous, they endure still. We have walked around them.

During the Cold War, Soviet controlled East Germany built its Berlin Wall virtually overnight to halt the haemorrhage of its population to the west and freedom, and it endured for thirty years with all its concrete, wire, guards, guns and deaths, until it fell, over thirty years ago, virtually overnight. And rejoicing Germans demolished it for souvenirs.

In Belfast, the capital of Northern Ireland, there are imposing walls that have actually stood longer than that in Berlin. Now called the the Peace Walls, they were first erected by the British army in 1969. They were temporary affairs of corrugated iron, as the inter-community conflict solidified and ossified, they were soon extended and upgraded to bricks, steel and concrete. The walls separated predominantly Protestant loyalist and Catholic nationalist enclaves throughout The Troubles, the three decades of bombings, murders, riots and civil-rights protests.

Though not all linked, 38 kilometres of walls still slice through the city, outliving the conflict that engendered them. Only some short sections have been removed – partly they’ve become a tourist attraction, while the communities that live closest to them say they still provide a sense of security – though tensions may have eased, people are easily divided and it’s much harder to bring them together again. In the Shankill and Falls roads area of western Belfast, which were particularly notorious during The Troubles, the wall is splattered with political messaging, which makes it easy to know which side you’re on. One side has portraits of British soldiers and the queen and kerbs are painted red, white and blue. On the other the colours of the Irish flag predominate, framing portraits of Republican heroes and hunger-strike martyrs.

Belfast’s Peace Wall

Walls or fortified fences are all the fashion in the Middle East. Egypt has built one on its border with Libya – and also with Gaza. Saudi Arabia has put one between it a Yemen and also, one with Iraq. Kuwait has one too with its former invader. In the Maghreb, Morocco constructed the longest wall in the world dividing the former colony of Spanish Sahara from its independence fighters in their Algerian sanctuaries; and yet, the modern world’s longest enduring independence struggle continues.

The Israelis built the Separation Wall to halt the bombings of buses and bistros in Jerusalem and Tel Aviv during the Second Intifada and have maintained it as an instrument of security and control and of divisive national politics. And on the whole, it has worked, except that it has entrenched the isolation from each other of the Israeli and Palestinian communities, and increased in many, a lack of familiarity and empathy and a mutual fear and loathing that does not auger well for peaceful coexistence.

If you walk atop the Ottoman Walls that still circle the Old City of Jerusalem, you can see it and the Haram Al Sharif, the Dome of the Rock, from where the walls pass Mount Zion. It snakes away in the distance through the arid landscape and white sandstone suburbs like an incongruous grey scar. We’ve crossed through the wall and IDF and Border Police checkpoints many times in our travels through Israel and Palestine. On one journey, a cross-country drive across the Judean desert from the satellite city of Ma’ale Adumin to the ancient and amazing monastery of Mar Saba, we passed through fields where Bedouin women harvested wild wheat with sickles as their forebears did of old and actually walked across the footings of a section of the wall that has been abandoned when the high court determined that its construction would prevent the Bedouin from traversing their traditional grazing grounds.

In his final book, Night of Power, published posthumously in 2024, the late foreign correspondent Robert Fisk provides a dramatic description of this “immense fortress wall” which snakes “firstly around Jerusalem but then north and south of the city as far as 12 miles deep into Palestine territory, cutting and escarping its way over the landscape to embrace most of the Jewish colonies … It did deter suicide bombers, but it was also gobbled up more Arab land. In places it is 26 feet or twice the height of the Berlin wall. Ditches, barbed wire, patrol roads and reinforced concrete watchtowers completed this grim travesty of peace. But as the wall grew to 440 miles in length, journalists clung to the language of ‘normalcy’ a ‘barrier’ after all surely is just a pole across the road, at most a police checkpoint, while a ‘fence’ something we might find between gardens or neighbouring fields. So why would we be surprised when Italian Prime Minister Silvio Berlisconi, traveling through the massive obstruction outside Bethlehem in February 2010 said that he did not notice it. But visitors to Jerusalem are struck by the wall’s surpassing gray ugliness. Its immensity dwarfed the landscape of low hills and Palestinian villages and crudely humiliated beauty of the original Ottoman walls Churches mosques and synagogues .. Ultimately the wall was found to have put nearly 15% of West Bank land on the Israeli side and disrupted the lives of a third of the Palestine population. It would, the UN discovered, entrap 274,000 Palestinians in enclaves and cut off another 400,000 from their fields, jobs, schools and hospitals”.

Leftwing Israeli journalist Amira Haas, who lives in the West Bank, takes Fisk on a tour of the wall:

“Towering 26 feet above us, stern, monstrous in its determination, coiling and snaking between the apartment blocks and skulking in wadis and turning back on itself until you have two walls, one after the other. You shake your head a moment – when suddenly through some miscalculation surely – there is no wall at all but a shopping street or a bare hillside of scrub and rock. And then the splash of red, sloping rooves and pools and trees of the colonies and yes, more walks and barbed wire fences and yet bigger walls. And then, once more the beast itself, guardian of Israel’s colonies: the Wall.

The Separation Wall between Jerusalem and Ramallah. Paul Hemphill 2016

Israel also built a forty-mile so-called smart fence around the Hamas-controlled enclave of Gaza, decked out with cameras, radars, and sensors. It was meant to both stop large-scale Hamas attacks and provide warning if Hamas was gathering its forces. This failed disastrously on October 7th 2023.

Those defenses, of course, did work for many years. The Hamas, which used to send numerous suicide bombers into Israel, was largely unable to penetrate the border from Gaza, in large part due to the fence. In fact, Hamas had to plan for several years and conduct a massive operation to overcome the defenses – not an easy task and one that should have been detected and disrupted by Israeli intelligence.

The Hamas’ assault on the black Shabbat demonstrated chillingly that defenses by themselves are never sufficient. They must be backed up by intelligence and a rapid-response capability, making any breach less consequential for Israel and potentially disastrous for Hamas. Indeed, had Israel been able to scramble a small number of attack helicopters to Gaza quickly as the assault force was breaching the fence, Hamas would have suffered huge losses.

Yes, walls work, until, for one reason or another, they don’t …

Aida Refugee Camp outside Bethlehem, Paul Hemphill 2016

An illusion of safety

I will ask more of you than any khal has ever asked of his khalassar! Will you ride the wooden horses across the black salt sea? Will you kill my enemies in their iron suits and tear down their stone houses? Will you give me the Seven Kingdoms, the gift Khal Drogo promised me before the Mother of Mountains? Are you with me? Now… and always!”

Danearys Targaryen, Game of Thrones

And they were, and they did, with the help, of course, of dragons.

While walls are destined to fall one day, people like walls. They project a language of security – but their construction stems from a sense of insecurity, an intense fear of losing what you have.

In an early post, The Twilight of the Equine Gods, we talked of the horsemen of the plains and steppes who descended violently upon the sedentary lands of Europe the Middle East and China. The folk on the pointy end of their depredations built walls to keep them out.

But while people feel safe behind walls, their impregnability is often illusory.

Walls have gates and these permit ordinary, decent folk to enter and exit – to work, to trade, to parlay, to mingle, communicate and court. The forts along Hadrian’s Wall tell the story of such coexistence and cohabitation. But some people don’t bother with gates. Thieves can scale them and climb over them. Enemies too – they clamber over them, dig under them, mine them and bring them tumbling down, or by subterfuge, they can suborn, beguile or bribe a turncoat or waverer to open the gates or reveal a secret entrance. The ancient Greeks bearing their dubious gifts brought down “the topless towers of Illium” with a ruse that launched a thousand analogies and the famous aphorism “beware Greeks bearing gifts”. The Greeks have never lived that one down.

I’ve had the privilege and pleasure of walking the corridors and standing on battlements of some of those great crusader castles of Syria and Palestine – of Qala’t al Husn, known to the world as Krak de Chevaliers, of Qala’t Salahuddin in Syria’s Alawite heartland, and Belvoir in Israel. These fell not by storm but by subterfuge – plants, turncoats or bribes By geological happenstance, these three significant citadels were built above the great Rift Valley that runs from Africa to Turkey and from their still imposing ramparts, the traveller can look out over several countries and appreciate the strategic importance of these man-made megaliths.

Krak de Chevaliers, Husn, near Homs, Syria. Paul Hemphill 2006

Krak de Chevaliers,Paul Hemphill 2006

The Golden Gate, Jerusalem, from Gethsemene. Paul Hemphill 2016

A world of walls

And the great and winding wall between us

Seem to copy the lines of your face

Bruce Cockburn, Embers of Eden

In his Booker Award winning novel Apeirogon, Irish author Column McCann’s Palestinian protagonist Rami, speaking of the death of his daughter at the hands of the IDF, says: “all walls are destined to fall, no matter what”. But Rami “was not so naive, though, to believe that more would not be built. It was a world of walls. Still, it was his job to insert a crack in the one most visible to him”.

Walls are in vogue nowadays. We declare that we should be building bridges, and yet, we keep building walls. Indeed, walls and wire define and divide the brotherhood of man.

Walls keep unwanted people out and nervous people in. Or prisoners – the world is full of those. The USA, The Land of the Free, incarcerates more than any other nation – except China. More than Iran, or Turkey, each with tens of thousands of political prisoners. The majority of inmates in American and Australian jails are black.

And walls protect us from “the other”.

Australian commentator Waleed Aly wrote in the SMH 9 November 2019: “A wall doesn’t just exclude. It obscures. It renders those on the other side invisible. And once people are invisible, they become mythological beasts. Their lives, their attitudes, their aspirations all become figments of our imagination”. Read the full article below.

To my thinking, this can apply to several of today’s intractable conflicts. The division between North and South Korea, for example, with its heavily weaponized DMZ. Iran and its ostensible enemies. And as I alluded to above, the walls that divide Israelis and Palestinians in the West Bank and in Gaza.

Back in the day, I would walk from Ramallah, then but a small town, to Jerusalem. I’d traverse the old city, and head up the Jaffa Road to the bus station and thence, to Tel Aviv. Today, there is the Separation Barrier and checkpoints, and exclusive roads – easier for visitors like ourselves as we traversed the Occupied Territories, but excruciating and humiliating for the tens of thousands of Palestinians who, until October 7, crossed into Israel daily to work “on the other side” and visit family and friends in East Jerusalem and in Israel.

Amira Haas describes the road I once walked down: “It’s a destruction of peoples life – it’s the end of the world. See here? We go straight to Jerusalem. Not now. This was a busy road and you can see here how people invested in homes with a little bit of grace, the strength of the houses, the stone. Look at the Hebrew signs because these Palestinians used to have so many Israeli customers”. But, Fisk writes, “almost all the shops are closed, the houses shuttered, weeds and sticks along the broken curb. The graffiti is pitiful, the sun merciless, the sky so caked with the heat that the grey of the Wall sometimes merges into the grey stone of the sky. “It is pathetic this place” Amira Hass says. I’ve always been showing it to people always, you know hundred times and it never stop shocking me”.

The border fence between Saudi Arabia and Iraq

The border fence between Kuwait and Iraq

Girt by sea …

That’s from our Australian national anthem, a paean to our pale Anglo-Celtic Christian heritage, continually updated as our values and our demography changes. It reminds us that walls are not necessarily built of bricks and mortar. An ocean can serve the same purpose.

The English, for example, have always rejoiced in their insular status. As early as the 13th century, an English chronicler described England as “set at the end of the world, the sea girding it around”. It was the sentiment which Shakespeare put into the mouth of the dying John of Gaunt in Richard II”: This precious stone set in the silver sea, which serves it in the office of a wall, or as a moat defensive to a house, against the envy of less happy lands.” It is part of the classic canon of English patriotism. Yet it was and remains a myth. As historian Jonathan Sumption, has pointed out, politically, England was not an island until defeat in the Hundred Years War made it one – had been part of a European polity.

Indeed, the aforementioned Hadrian’s Wall served as a more strategic historical reference point. In the preface to Pax, the latest volume of his magisterial history of the Roman Empire, English historian Tom Holland notes that the northern bank of the river Tyne was the furthest north that a Roman Emperor ever visited. What was so important about Hadrian’s visit to Tyneside in 122AD was his decision there to mark in stone, for the first time, the official limits of his Empire. North of this great wall, there was paucity and unspeakable barbarism, scarcely worth bothering about; below the wall was civility and abundance and the blessings of Romanitas. To this day, those 73 miles of the Vallum Hadriani across the jugular of Britain still shape the common conception of where England and Scotland begin and end, even though the wall has never delineated the Anglo-Scottish border. For this colossal structure left enduring psychological as well as physical remains. To the Saxons, it was “the work of giants” and was often thought of as a metaphysical frontier with the land of the dead – George R got that part right too.

The “sceptred isle” tag prevails, but. It’s how many Brit’s saw themselves back then and right up to the sixties when we had to memorise it at grammar school: This earth of majesty, this seat of Mars, this other Eden, demi-paradise, this fortress built by Nature for herself against infection and the hand of war. This happy breed of men, this little world”. I couldn’t resist quoting it.

Our Island Story: A Child’s History of England, by British author Henrietta Elizabeth Marshall, first published in 1905, covered the history of England from the time of the Roman occupation until Queen Victoria’s death, using a mixture of traditional history and mythology to explain the story of British history in a way accessible to younger readers. It depicted the union of England and Scotland as a desirable and inevitable event, and praises rebels and the collective will of the common people in opposing tyrants, including kings like John and Charles I. It inspired a parody, 1066 and All That. Former Prime Minister David Cameron chose the book when asked to select his favourite childhood book in October 2010: “When I was younger, I particularly enjoyed Our Island Story … It is written in a way that really captured my imagination and which nurtured my interest in the history of our great nation”.

Maybe the Island Nation prevailed in its time – notwithstanding John Bull’s Other Island just over the water and the “troubles” it caused. But the French port of Calais that was such a headache to the Plantagenet kings back in the day is a persistent migraine today as folk from faraway places arrivethere hoping to board flimsy boats, casting their fortunes and their lives to the waves of one of the world’s busiest and tempestuous sea ways in the hope of a better life in the green and pleasant land of song and story.

We in Australia do have a unique wall – the ocean surrounding us.

Our former and now disgraced Australian prime minister Scott Morrison prime minister once declared that he himself was a wall, barring what we in official Australia call unauthorized arrivals by sea. The wall surrounding our continent – we are indeed the only nation that covers exclusively its own continent – is a wide watery one – huge, forbidding, and, depending on the operating budget and competence of the Australian Border Force, impenetrable. And it costs is a motza. In December 2020, The Guardian reported that Australia will spend nearly $1.2 billion on offshore detention – it’s called “processing” – that financial year, even though fewer than 300 people remained in ‘offshore detention” in Papua New Guinea and Nauru That’s roughly $4m for each person. Our government has spent more than $12 billion on offshore processing in the past eight financial years.

It might be less than the US$20 billion President Trump wanted to waste on a border wall, but it is far more as a proportion of government revenue and national income and more than five times the UN refugee agency’s entire budget for all of Southeast Asia.

That’s all from me. The reviews follow, but first some of the articles referred to in my narrative.

© Paul Hemphill 2024. All rights reserved.

Al Tariq al Salabiyin – the Crusaders’ Trail

Roman Wall Blues – life and love in a cold climate

The Twilight of the Equine Gods

Waleed Ali, Sydney Morning Herald, November 7, 2019

Sometimes that is literal as in the case of Donald Trump most famous, still unfulfilled promise. Sometimes this is figurative as in the case of Brexit (though it has dangerously literal implications in Northern Ireland). And sometimes this is a particularly pointed development, as in the case of countries that were once part of the Soviet bloc, which have turned in sharply illiberal, nationalist, anti-immigrant directions: places like Hungary and Poland.

Even as far afield as Australia we are being lightly stalked by this fortress mentality, too. Mostly this has focused on boats, but it is spreading now to a populist suspicion of globalisation more generally, especially where it involves us having obligations to other countries or the environment.

I don’t want to stretch the comparison too far. Today’s walls are about excluding the foreigner, while the Berlin Wall was built for the opposite reason: to keep East Germans in. But there is still an important continuity here, something powerful and important in the idea of a wall, that makes it so symbolic, whatever immediate function it serves. More profound than the physical barrier is the psychological one. That’s as true today as it was in Berlin.

Konrad Schumann leaps the barbed wire into West Berlin on 15 August 1961

Children at the Berlin Wall on Sebastianstrasse, around 1964 (Lehnartz/ullstein bild, Getty Images)

The fall of the Berlin Wall, November 1989

These narratives tell an uncomplicated story of the other that is really designed to tell an uncomplicated, heroic story about oneself. The East’s imagined multitudes of poor Westerners was a way of saying the Eastern system was superior and just. Hence, the West had to be wild and unequal. Meanwhile, the Western story of the East was a way of eliding its own shortcomings, establishing a triumphant narrative of freedom that swept away concerns about social injustice.

Walls make this so much easier. Aside from all else they do, walls prevent us from knowing each other. That has serious real-world consequences. We call the period after the Berlin Wall fell “reunification”, but it was really a Western annexation of the East. East became West, not some other accommodation. So thorough was the West’s self-regard, so comprehensive its belief in the East’s unmitigated bleakness, that it respected none of the institutions the East had built. It privatised and sold off its industries to the highest bidder – inevitably West Germans. It shut down its companies, more or less assuming they had nothing to offer.

The result saw East Germans with little choice but to head West for jobs, and the East hasn’t quite recovered. Today it is older, poorer, and endures higher unemployment. It’s only by knowing this that we can understand why a government study found 38 per cent of East Germans think reunification was a bad thing. A majority feel they are now second-class citizens. We’re seeing a rise of far-right radicalism, even neo-Nazism, in Germany. Its heartland is in the East.

Today’s walls are built on the same logic. They all offer some self-aggrandizing view of the world in which everyone else deep down wishes they were like us. Whether believing in the eternal supremacy of the British Empire in the case of Brexit, or that asylum seekers are really more interested in finding a back door to Australia than they are in fleeing persecution, the foreigner exists mostly as a counterpoint to our own magnificence. What matters is that they remain unknown and unknowable so we can mould them to our opposites, and they can be scapegoated for our problems.

We’re so committed to this kind of psychology that we will establish walls precisely where we’re told they can’t be built. Even something as borderless as the internet has become a landscape of barricades, populated by people talking only about their enemies and only to their friends. As a result, almost no one is knowable anymore.

So let me add one more idea to this week’s litany of Berlin Wall reflections: that it be a symbol of human arrogance. The arrogance to control and lie to one’s own people, sure. But the arrogance of choosing isolation, too. The arrogance of believing that the other has nothing to offer us. And the arrogance of believing that we can be fully formed in others’ absence; of treating other people as mere raw material from which we can manufacture ourselves.

Waleed Aly is a regular columnist and a lecturer in politics at Monash University.

A crash course in barrier building

Walls: a history of civilisation in blood and brick by David Fry Faber 2018.

Reviewed in the Australian by Pat Shell, March 16, 2019

“Build bridges, not walls. It’s a slogan”, writes Frye (Ancient and Middle Eastern History/Eastern Connecticut State Univ.), “designed to give military historians fits.”

Bridges, after all, have military purposes: to get across moats and earthworks and to ford rivers into enemy territory. Walls, on the other hand, make peace – history offers plenty of examples, he writes, to show that “the sense of security created by walls freed more and more males from the requirement of serving as warriors.”

Indeed, by Frye’s account, walls are hallmarks of civilization, if ones that are easily thwarted.

One of his examples is the Tres Long Mur, a defensive structure built more than 4,000 years ago, stretching across the Syrian desert and shielding some of the world’s oldest towns from marauders from the steppes beyond. There are mysteries associated with the ruins, just as there are with the Great Wall of China, another of Frye’s examples—and one that proves, readily, that where walls go up, people find ways to get around and over them.

The author’s pointed case study of Hadrian’s Wall shows that it may not have been a defensive success, but that does not mean it didn’t have a defensive purpose, as some scholars have recently argued. As he writes, wittily, “there is little to be gained from rationalizing an irrational past.”

Another defensive failure is the Maginot Line, which became more symbolic than practical in an age of modern tanks; on the reverse side are spectacular successes, such as the great walls of Constantinople, which shielded the city from siege by as many as 200,000 soldiers of the caliphate, “one of the greatest turning points in history.”

Walls have many purposes, he concludes, and it is rather ironic that the matter of walls is often as divisive as a wall itself.

A provocative, well-written, and – with walls rising everywhere on the planet – timely study.

Walls work, and walls save lives. So declared Donald Trump in the 2019 State of the Union address. Not long after that, he went a step further, just clearing Congress’ refusal to front with the funds for 4 billion bricks to be a national emergency.

There are times when that view could be right. How a well-built levee might postpone the inevitable when the rain keeps fallin’ and the river done rose. For a while it least.

But the US president wasn’t talking about breakwaters and climate change mitigation. The tsunami he is hoping to surf home to a tsecond term is a tidal bore of human flesh. He thinks that a Mexican wall is needed to keep out rapists, drug dealers, terrorists and Venezuelan communists.

But his wall, if ever built, will never achieve what wall builders through the ages have vainly striven for: to stop time itself, to freeze history at the pinnacle of their power. And in so doing, through the erection of military masonry on a monumental scale, confidently wallow in the triumphant delusions screamed by Ozymandias at weary gods who have heard it all before.

In short, the inevitable corollary of the invention of Real Estate: the creation of an exclusive neighbourhood to keep out riffraff.

Walls, David Frye’s fascinating and timely analysis of the rise and fall of empires, religions, cultures and languages, is so compellingly readable because it urges to look closely at human artifacts so everyday, so ordinary that we only rarely see them as instruments of power and authority. They can be impressive, sure, but not like an aircraft carrier steaming lies and all the flight of the two banners overhead.

We walk past walls every day. We live behind them. They hold up our roofs. Once fitted with a solid locked door and the steel-grated windows, they protect us, and not just from the wind and the rain.

Frye is an American historian. His main point is not just that walls, the stone and earthen shield of homesteads, palaces, towns, indeed entire nations, are as old as civilisation itself. He thinks that for all intents and purposes, walls are civilisation itself, or, at the very least have allowed civilisations to come into being.

He reminds us that like armies, walls don’t go anywhere. Like armies, they can be enormous, and symbolic of great power and proprietary rights, but they rise and fall in situ, and define the status of all who live around them.

Either you live inside the wall, or you don’t. And depending on how you define civilizations, they rarely flourish without a stable address of some sort. The Athenians wouldn’t have bothered building the Parthenon if they’d had to pull it down every winter to follow their goats to Macedonia in search of greener pastures. But they had to be able to go to bed at night confident that the marvels of the Acropolis would still be there in the morning.

And while the kind of people who write and read books such as Walls are by definition “inside the wall” characters, Frye notes the disdain with which “basket carrying” sybarites were regard by those on the outer.

The barbarians, the hordes. The marauding warriors. Luxury is for wimps, art an affectation citation for the feeble and effete. The Huns, Mongols, Cossacks, Names that are synonymous for people who would rather burn a city to the ground than simply move in and celebrate their luxurious residential arrangements by draining the wine cellars and frolicking in the fountains.

When the great unwashed arrived in sufficient numbers to break down the ramparts, they didn’t mess around. To them, plumbing, hanging gardens, marble theatres and elegant geometry will not try ounce of human aspiration, but conversions.

It is this primal fear of defenses overwhelmed that fuels Trump’s calculated hysteria today. While he may, without quite saying it in so many words, be grasping for historical legitimacy by asking his countrymen to “Remember The Alamo”, He does play on fears food in for thousands of years of siege warfare, and the grizzly fates that befell the losers.

And while the discounted insurance premiums that come with the electrified fences and gated communities of Bel Air and Rhode Island might ease the terror of wealthy Americans, a home invasion is small beer compared to the total collapse of “homeland security” in the real world.

Of the examples Frye gives of barriers breached and the resultant bloodbaths, and there are many, perhaps the most extraordinary is the Mongol demolition of Thirteenth Century China. “ The population of China fell from a 120 million in 1207 to 60 million in 1290. Mongols “boasted that they could ride over the sites of many former cities without encountering any remains high enough to make their horses stumble”.

Genghis Khan, born and bred on the merciless steppe, saw Chinese sophistication as an affront to nature, much as the Spartans mocked the music and theatre of the Athenians.

He shrugged off the carnage and destruction he had wrought as nature’s mockery of Chinese hubris and pretensions: “Heaven is weary of the beauty of the inordinate luxury of China”.

Trump doesn’t care for it much either, it seems. Perhaps a wise adviser might take a moment to point out to him the bridges are usually a far better long-term investment than barbed wire.

as The Eurasian Steppe by the archaeologist Warwick Ball makes clear, rather than a semi-wild anteroom to the continent, “the history, languages, ideas, art forms, peoples, nations and identities of the steppe have shaped almost every aspect of the life of Europe”. Europeans from further west have for centuries been prone to viewing the steppe as the haunt of wild tribes, and the source of occasional, fearsome destruction.

https://unherd.com/2022/07/the-fate-of-europe-lies-in-the-steppes/

Review of Walls: history of civilisation in blood and brick

John M. Formy-Duval, retired teacher of ancient and medieval history and educator, on this books and reading blogspot.

In Walls: a History of Civilization in Blood and Brick, David Frye has written an encompassing and enlightening review of walls through the centuries, ranging from 2000 B.C. to the present. A “Selected Timeline” covers the subject matter in four geographical areas: Near East and Central Asia; Europe; China; and the Americas. Frye writes that walls can take the form of “protectionist economic policies,” a “great internet firewall,” razor wire with motion sensors, or concrete barriers. Stringent, punitive immigration policies around the world seek to keep the perceived destroyers of “our culture out.” That is, we belong here; you do not.

“Few civilized people have even lived without them,” Frye emphasizes. From ditches to sapling fences to berms to walls, the level of sophistication rose as people perceived an increasing need for protection from, literally, the barbarians at the gate. Farmers settled and fortified their small villages. Even today one finds fences around Maasai villages in Tanzania. As villages transitioned into cities, their walls grew with them, often into great defensive bulwarks. Even Shakespeare’s Juliet recognized that “these walls are high and hard to climb.”

The epilogue “Love Your Neighbor, but Don’t Pull Down Your Hedge” covers the period from 1990 to the present. This section begins and ends with an account of how the Malibu coastline transitioned from the single ownership of May Rindge in 1892 until 1926, when she grudgingly agreed to lease some properties after numerous shootings, sheep poisonings, and a Supreme Court decision that went against her. Focusing on the present, Frye embarks on an account of the spate of walls built since the Berlin Wall was torn down. From the United States to the Middle East to Southern Europe and India, and nearly everywhere else, it seems, the pace, enormity, and sophistication of these walls is astounding.

People are familiar with the walls Israel has erected in which “infrared night sensors, radar, seismic sensors for detecting underground activity, balloon-born cameras, and unmanned, remote-controlled Ford F-350 trucks, equipped with video cameras and machine guns, augment the wall’s concrete slabs and concertina wire.” Lesser known is Saudi Arabia’s effort, begun in 2003, to create a barrier across its eleven-hundred-mile border with Yemen. The barrier rises across the desolate Empty Quarter, home of significant oil reserves. “Ten-foot high steel pipes, filled with concrete” provide the frame for razor wire while tunnels burrow deep underground. The Saudis have a second, more heavily fortified wall that ranges six hundred miles along their border with Iraq. Egypt, Jordan, India, Thailand and Malaysia, Morocco and Algeria, and Kenya are also in the wall-building business, often with funds or construction assistance either from the United States government or private businesses.

The U.S. was in the wall-building business along our border with Mexico long before the present administration, although the present focus changed the dialogue. We had barriers, little more than fences, before the Berlin Wall fell. Under President Clinton, for example, extensions were added to the existing barriers in 1993, 1994, and 1997. After Berlin, however, the word “wall” was largely abandoned in favor of softer language, and in 2006 the “Secure Fence Act” extended the extensions undertaken during Clinton’s time in office. Who knows what will happen at the present time?

Walls have deep effects on us. They box us in; they shut us out; they keep others out. They come in physical form, but they can be purely psychological, designed to prevent us from sinking into “the other side of the tracks.” Professional nomenclature excludes people and gives the holders of the language key a sense of superiority. Myriad iterations of “wall” provide endless means to isolate us and keep them out.

Frye provides the who, what, where, when, and how of walls ancient and modern. The Great Wall and Hadrian’s Wall are generally known, but he touches on the thousands of walls that continue to exist today and continue to be built “while we wait on everyone else to become just as civilized as we are.”

About Walls

Review in Always Trust in Books blog

For thousands of years, humans have built walls and assaulted them, admired walls and reviled them. Great Walls have appeared on nearly every continent, the handiwork of people from Persia, Rome, China, Central America, and beyond. They have accompanied the rise of cities, nations, and empires. And yet they rarely appear in our history books.

Spanning centuries and millennia, drawing on archaeological digs to evidence from Berlin and Hollywood, David Frye uncovers the story of walls and asks questions that are both intriguing and profound. Did walls make civilization possible? Can we live without them?

This is more than a tale of bricks and stone: Frye reveals the startling link between what we build and how we live, who we are and how we came to be. It is nothing less than the story of civilization.

‘The creators of the first civilisations descended from generations of wall builders. They used their newfound advantages in organization and numbers to build bigger walls. More than a few still survive. In the pages that follow, I will often describe these monuments with imposing measures – their height, their thickness, sometimes their volumes, almost always their lengths. These numbers may begin to lose their impact after a while. They can only tell us so much. We will always learn more by examining the people who built the walls or the fear that lead to their construction.’

David Frye’s Walls is a classic non-fiction read that left me not only well informed but with a deeper appreciation and understanding of world history. From 10,000 B.C right up to the present day, David Frye explains how fundamental the invention, construction and development of walls were (and still are) to the progression of humanity. If you are here purely for a history of walls then you may be disappointed as DF is more interested in the influence instead of the existence of walls. DF took me on a guided tour through key periods in the history of mankind and how the creation (and protection) of walls allowed us to flourish as a species but also the ramifications and innovations that they led to later on.

DF lead me through civilisations that either accepted or rejected the concept of being walled (or caged) in and how their decisions affected the population and also the other nations around them. Walls redefined our ability to exist in a barbaric world and allowed us to focus on scientific and cultural advancements. It also allowed some kingdoms to go soft, so to speak. DF also focuses on the absence of walls and how it changed the civilisations who refused to hide behind them; nations like the Spartans, Mongols and Native Americans who lived to fight for what was theirs or claim new lands for themselves.

The amount of coverage is exceptional, from the Roman Empire, Mesopotamia and China (with their many great walls) to Greece, Constantinople and Berlin. Walls are essential to the telling of history and David Frye did a fantastic and immersive job with his writing. Informative, concise, engrossing (narrative elements), well structured and paced out, David’s writing made this book totally worth my time. He could have easily knocked out this book with his extensive knowledge of war and culture but he went the extra mile. Making connections, observations and theories that made the content more comprehensive and digestible (with some hilarious comments too).

Recent history seems in part to be governed by a chain reaction that saw the building of more and more elaborate walls. Each emperor saw fit to out do their predecessors or competition. Each iteration of wall has its successes and failures, while destroying them advanced weaponry and military tactics along the way. I loved spending time with different time periods and walking amongst the mythos, history, socio-economic backgrounds, knowledge and statistics surrounding the world’s walls and those compelled to build them for their own needs or the needs of many. I especially enjoyed how David Frye’s message about walls was fluid and how it evolved over the course of the book. How humanity grew out of their need for walls and yet still see them in a symbolic nature. How destroying a wall can be as powerful as building one.

Frye knows perfectly where to stop and elaborate or move on to new points. He also doesn’t shy away from the darker shades of history so be aware of graphic detail. There is a lot to learn in this book but DF has written it in a way that it is never too much and I always wanted to know more. There are many highlights to Walls and I can’t recommend it enough to Non-Fiction lovers of many varieties. If you like detail, history, mythology (and ghost stories), the many aspects of building civilisation and humanity’s past then Walls is a great book to get stuck into. We owe walls our lives and without their protection our societies would have never been the same.

‘The walls alone have seen the truth, and they are mute’

David Frye

A native of East Tennessee, David Frye received his Ph.D. in late ancient history from Duke University in 1991 and is presently a professor of history at Eastern Connecticut State University, where he teaches ancient and medieval history. Frye’s academic articles have appeared in the UK, Germany, Sweden, and Denmark, as well as the United States, in journals such as Nottingham Medieval Studies, Classical World, Byzantion, Historia, Hermes: Zeitschrift fur klassische Philologie, The Journal of Ecclesiastical History, and Classica et Mediaevalia. In addition, he has published in various popular archaeological and historical magazines and on the online humor site McSweeney’s. As part of his research, he has participated in archaeological excavations in Britain and Romania. (Goodreads Biography)