“Bliss it was in that dawn to be alive, but to be young was very heaven”.

The famous line from that old romantic William Wordsworth evokes a degree of nostalgie for les temps perdue. And so it is with the many published recollections and reveries surrounding the fifties anniversary of “les évènements de Mai” 1968. Perhaps we would be better served with Charles Dickens’ take on an earlier French Revolution:

“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair, we had everything before us, we had nothing before us, we were all going direct to Heaven, we were all going direct the other way – in short, the period was so far like the present period, that some of its noisiest authorities insisted on its being received, for good or for evil, in the superlative degree of comparison only”.

As German social historian Ulrich Raullf has written: “Our historical memory is a motherland of wishful thinking, sacrificed to our faith and blind to known facts…This is why historical myths are so tenacious. It’s as though the truth even when it’s there for everyone to see, is powerless – it can’t lay a finger on the all powerful myth”. During the closing scenes of the western The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, a journalist says: “This is the West, sir. When the legend becomes fact, print the legend”. And so it is with that Paris Spring.

To those of us who were young and politically progressive in those dear dead days, the protests, strikes and other forms of civil unrest of that springtime in Paris offered a mix of hope and vicarious adventure.

It was not simply a fight against something, like the Vietnam War that was raging at the time. Rather, It was a fight for something – for social change, for new forms of political, economic, social and class relations. We believed change was in the air, and there was a palpable frisson (such a great French word) of excitement.

We’d all read our Communist Manifesto, that mercifully brief and breathless primer for wannabe rebels, and now, to misquote old Karl Marx (ironically, two hundred years old this month), a spectre was indeed haunting Europe. Anything could happen. The future was unwritten. Regimes could tumble, and old ways crumble. Everything was mutable, impermanent – an idea that was simultaneously uplifting and terrifying.

We watched these events from across the La Manche with admiration and not a little envy. Our perspective may have been obscured, coloured and tittilated by distance and the biases of mainstream media, and by the pictures and the posters that found their way onto bedsit and bedroom walls. But there was not the 24/7 syndicated saturation that we get nowadays nor the live tweets and FB posts from the Sorbonne.

As Mitchell Abidor wrote recently in The New York Times: “The images … which changed my life when I was a teenager watching them on TV, are still burned in my memory: the enormous marches through the streets of France’s major cities; the overflowing crowds of people speechifying and debating in the amphitheater of the Sorbonne; workers occupying factories and flying red flags over the gates; students occupying universities and being beaten by the police. Workers and students, it appeared, were united against a sclerotic Gaullist state…These were images of the previously unimaginable: a revolution in the modern West. Revolution was no longer something that happened only in the past, or elsewhere, or in theory”.

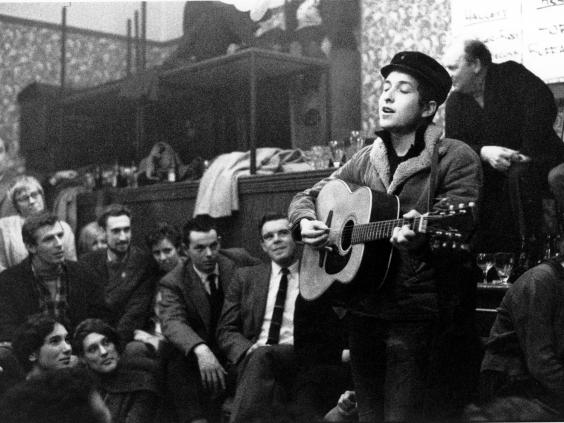

Mick Jagger later explained how he and Keith Richards came to a compose one of the Rolling Stones’ seminal songs, released that August on Beggars Banquet: “Yeah, it was a direct inspiration, because by contrast, London was very quiet…It was a very strange time in France. But not only in France but also in America, because of the Vietnam War and these endless disruptions … I thought it was a very good thing at the time. There was all this violence going on. I mean, they almost toppled the government in France; de Gaulle went into this complete funk, as he had in the past, and he went and sort of locked himself in his house in the country. And so the government was almost inactive. And the French riot police were amazing”. And so the Stones sang:

Everywhere I hear the sound of marching, charging feet, boy

‘Cause summer’s here and the time is right for fighting in the street, boy

Well what can a poor boy do

Except to sing for a rock ‘n’ roll band

‘Cause in sleepy London town

There’s just no place for a street fighting man

We all have differing memories and perspectives of those days, as do today’s commentators who may or may not have been born back then, or lived of the far side of the world, and who in these polarised times, cleave to tediously turgid talking points.

News Corp opinionistas and others on the right have put it all down to the nihilistic nonsense of pampered youth, using it as yet another stick which to beat the virtue-signalling, politically correct, young culture warriors of today. And on cue, The Australian’s resident Ayn Randista Janet Albrechtson is particularly possessed of the perception that a “wabble of woudy webels” holding our universities hostage to what she sees as a virulent post-modern anarchism identical to the apparent hedonist nihilism of the students of Paris. But many on the left are also captive of binary thinking, looking back on the events as a grand and glorious upsurge of worker and student solidarity and revolutionary zeal – a latter-day replay of the Paris Commune (another doomed Intifada that ended with firing squads during le semaine sanglant”. And then there are others who view it today as the political equivalent of coitus interruptus, remembered all over the world this year as a great missed opportunity, and the end of a revolutionary illusion. But, as the selection of articles featured below demonstrate, in retrospect, it probably a mix of all three, and maybe, even, none at all …

To many contemporary commentators, the violent unrest that shook Paris through May 1968 was driven by a cathartic reaction to a national feeling of ennui. After decades of economic growth, high employment rates, rising living standards, and a burgeoning educational system, France was bored – with the ageing but immovable and indomitable President Charles de Gaulle, and with a stultifying, bureaucratic, “father knows best” vein that ran through the public, political and social establishment, through administration, education, industrial and sexual relations.

The times they were a’changin’, but the ferment, the fashion, the fun that roiled and rock ‘n rolled the US and even staid and stitched-up Great Britain, had somehow bypassed La France – 1968 did not begin in Paris, but in Berkeley, California around 1965, where the Vietnam protests originated, spreading by early 1968 to Britain and to Germany. Viewing photographs of the sit-ins, demonstrations and street-battles, commentators remark on the straight appearance of the students with their sports jackets, ties and long skirts, and “short back and sides” haircuts, such a long way away from London’s Carnaby Street and California’s Summer of Love. To borrow again from Karl, the French has nothing to loose but their chains.

No doubt there was indeed a fair dose of teen rebellion during that Parisian prima vera. But there was much more to it than just wild oats, teen spirit, a cursory reading of Marx, Mao and Marcuse, and a battle cry of Egalité! Liberté! Sexualité! It takes more than the desire for a yahoo to take to the streets for a month of barricades and cobblestones (so French and red chic!) in the face of paramilitary batons, water-cannons and teargas. Though it must be said that the French do Revolution extremely well. It doesn’t mean that they succeed. Indeed. Most have failed, and have ended badly with blood on the streets, betrayal and retribution.

But there were in, effect, three Mays, each of them quite distinct and different.

There was the May of the students, which we all recall so well in our own subjective hindsight, a protest against the rigidity and hierarchy of the French university system, defying the historical deference of young people to their elders, and yes, demanding more sex!

Then was the May of the workers with their call for higher wages, less hours, and consultation with management. Some ten million people came out on strike and brought the factories of France to a virtual standstill. They were, despite the slogans of worker-student unity, no true friends of ostensibly spoiled middle class student firebrands and their foreign pals. They joined the revolution for their own sectional and economic reasons, and the end, the state represented by Jacques Chirac, secretary of state for employment, and the unions, led by the Communist Georges Séguy, agreed that the revolt had to end, and negotiated tremendous pay increases, a shorter working week, the strengthening of workers’ councils, and much more.

And there was a third May – an “anti-May even – that ultimately carried the day, one that the students failed to take into account and which their left wing heirs have often ignored. On May 30, half a million people paraded on the Champs-Élysées in support of President de Gaulle – perhaps the largest demonstration of the month. The France that the students were rebelling against, one they thought was all but dead, turned out to be very much alive – and eager to put rebellious youth back in its place. Charles de Gaulle emerged triumphant from the elections in June. And the political right remained in power in France until the victory in 1981 of François Mitterrand and his very un-1968 brand of socialism.

In the wings was the maker and breaker of kings and communes: the French Army, the traditional bulwark of successive French Republics, and the strong arm up canny conjurer Charles de Gaulle’s sleeve. Then there were those half a million French men and women who took to the streets at the fag end of the month to defend the staid and safe republic. De Gaulle had at first been nonplussed by the students, describing them at one point as chienlit – literally, “shit-a-bed” – youngsters and and shocked by the scale of the strikes, and even briefly fled France for Germany whilst he recalibrated. And finally, when Le President had made his feints, and done his deals, and went to the people, he was re-elected in a landslide in an anxious conservative backlash.

The revolution, such as it was, kind of faded away, much like Marx has reckoned the state would fade away. The students went back to their crowded classrooms, and the workers, to higher wages and a shorter working week. And those who John le Carré might’ve called “the many too many” returned to the safe, serene, suburban lives. God was in his heaven and de Gaulle back in the Élysée Palace.

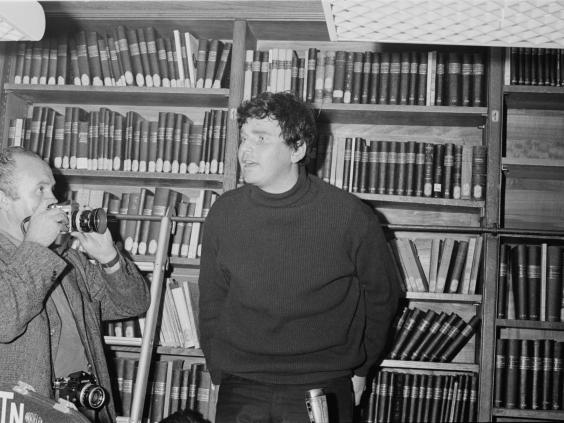

Since then, the French left has been reduced to a shadow of its former self, while the right and neoliberalism have grown ever stronger. As for “les soixante-huitards”, some have become grumpy old men, and conservatives even. Others, like Daniel Cohn Bendit, Sorbonniere firebrand Danny Le Rouge, and now a Green, German member of the European Parliament, are open to new ideas and changing times.

Chou En Lai, China’s premier at the time, was asked of the French Revolution – the big one, that is, if 1789 – whether he thought it was a good thing. “Its too early to tell” he replied. As many conservatives are eager to point out, he seems to have been talking about May 1968.

But, after May 1968, “all changed, changed utterly”, to quote WB Yeats. As the Bobster had written just a few years prior, the line had been drawn and the curse had been cast, and the order was rapidly fadin’. The old dispensation of patriarchal authority and catholic morality had been mortally wounded. the Karl’s chains had indeed been broken and France had entered the swinging ‘sixties.

That’s all from me. Read on and enjoy the stories and loads of fabulous pictures … or you can listen to historians Tom Holland and Dominic Sandbrook’s informative and also, amusing account on my favourite podcast, The Rest Is History: https://podcasts.apple.com/au/podcast/the-rest-is-history/id1537788786?i=1000622076100

And here are other posts in In That Howling Infinite with regard to the ‘sixties: Encounters with Enoch; Recalling the Mersey Poets; The Strange Death of Sam Cooke; Looking for Lehrer; Shock of the Old – the glory days of prog rock; Window on a Gone World; Back in the day; The Incorrigible Optimists Club.

The Paris riots of May 1968: How the frustrations of youth brought France to the brink of revolution

Fifty years ago today the streets of Paris staged a battle between 6,000 student demonstrators and 1,500 gendarmes – within days it had snowballed into civil dispute that saw 10 million French workers go on general strike and brought the economy to a virtual halt. Andreas Whittam Smith recalls the events of ‘Mai 68’

Egalité! Liberté! Sexualité!: Paris, May 1968

https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/europe/egalit-libert-sexualit-paris-may-1968-784703.html

Just six weeks after France’s leading newspaper, Le Monde, pronounced that the country was “bored,” too bored to join the youth protests underway in Germany and in the United States, students in Paris occupied the Sorbonne, one of the most illustrious universities in Europe.

The day was May 3, 1968, and the events that ensued over the following month — mass protests, street battles and nationwide strikes — transformed France. It was not a political revolution in the way that earlier French revolutions had been, but a cultural and social one that in a stunningly short time changed French society.

“In the history of France it was a remarkable movement because it was truly a mass movement that concerned Paris but also the provinces, that concerned intellectuals but also manual workers,” said Bruno Queysanne, who, at the time was an assistant instructor at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, one of the country’s most prestigious art and architecture schools.

“Each person that engaged, engaged himself all the way,” he said. “That was how France could stop running, without there being a feeling of injustice or sabotage. The whole world was in agreement that they should pause and reflect on the conditions of existence.”

Today it is hard to imagine a Western country completely engulfed by a social upheaval, but that is what happened in May 1968 in France. It is hard to find any Frenchman or woman born before 1960 who does not have a vivid and personal recollection of that month.

“Everything was enlarged by 1968; it determined all my life,” said Maguy Alvarez, a teacher of English to elementary school students, as she walked through an exhibition of posters and artworks from the period.

Both the women’s liberation movement and the gay rights movement in France grew out of the 1968 upheaval and the intellectual ferment of the time.

While some people saw the mass strikes and protests as a shattering and painful event that upended social norms — the authority of the father of the family and of the leader of the country — for most, it pushed France into the modern world.

“The 19th century was a very long century,” said Philippe Artières, a historian and researcher at the National Center for Scientific Research and one of the curators of the show on the posters of 1968.

“We’re hardly out of it, and you have to keep in mind that in ’68 we were just 50 years after the revolution of ’17 and a century after the Paris commune,” he said, referring to the Russian Revolution and the 1871 uprising by mostly poor and working class residents of Paris (although the leadership was middle class) that was brutally put down, leaving as many as 10,000 dead.

President Emmanuel Macron, who was born in 1977, is the first post-1968 French leader not to have personal memories of the upheaval — the exhilaration, the sense of possibility, and the potential power of the street.

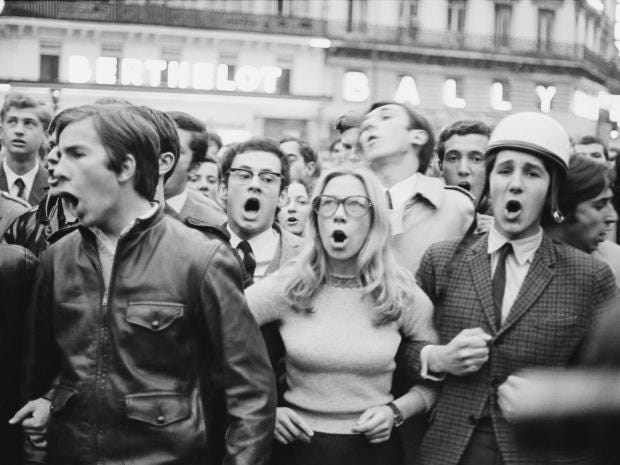

Universities across the country shut down as students, often joined by their professors, occupied the classrooms and courtyards. In Paris and other major French cities, workers, students, intellectuals and anyone else who was interested thronged into the street for mass rallies.

Blunting the sense of exhilaration were the daily confrontations with the police. As early as May 3, police charged into the Sorbonne and ousted the students; in the ensuing melee, some 600 were arrested, according to Agence France-Presse.

The students returned and quickly set up barricades to stop the police from entering the areas where they were massing. The two factions faced off night and day: The police wearing helmets and armed with riot shields, tear gas, truncheons and water cannons; and the university students, sometimes still wearing the ties and jackets mandated at the time by the university administration. The students dug up paving stones from the Paris streets to heave at the police.

The night of May 6 was particularly violent, with 600 people wounded and 422 detained, but it was overnight between May 10 and May 11, known as the “night of barricades” that people still talk about.

The protesters ripped up the paving stones from two streets in the Latin Quarter, where the Sorbonne is, set fire to cars and confronted the police. By the time the bloody fighting ended, hundreds of students had been arrested and hundreds more hospitalized, as were a number of police officers.

“During the night there were very violent protests, cars burned, things broken, but during the day, there was an air of vacation, of summer, a relaxed feeling,” said Mr. Queysanne, who later became a professor of the philosophy of architecture at the University of Grenoble and then at the Southern California Institute of Architecture in Los Angeles.

“But then the next day, people came and discussed what they had seen; some were for, some were against. This was incredible, there was freedom of speech, words were set free.”

Amazingly, somehow the violence did not taint the euphoria of the protesters.

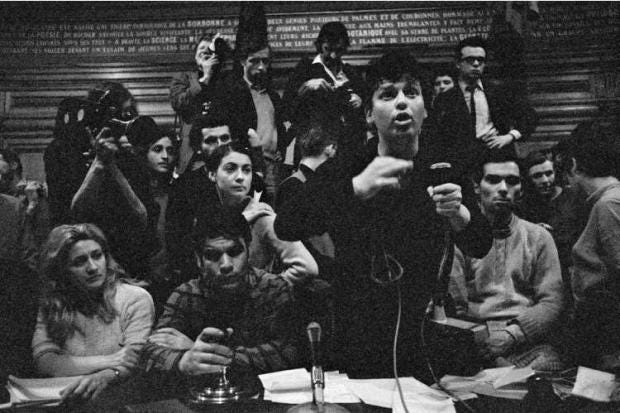

“The feeling we had in those days, which has shaped my entire life really, was: We’re making history. An exalted feeling — suddenly we had become agents in world history,” said Daniel Cohn-Bendit, the most prominent of the student leaders at the time, in an essay in the May 10 issue of The New York Review of Books.

Simultaneously with the student protests, France’s factory workers walked off the job and in many places camped out on the factory floor, refusing to work and demanding a new order.

The shipyards in Nantes stopped loading and unloading freighters, and work in much of the car manufacturing and aeronautics industries also ceased. The unions did not call the strikes but when workers and students embraced them, they acquiesced.

By the third week in May, between 10 and 11 million people were on strike. There was no gas for cars because the refineries came to a halt; the trains did not run, nor did the Paris Metro.

In France, the enemy of change was the government, then headed by President Charles de Gaulle, who tried to repress the strikes and the sit-ins, but on May 29, he appeared to be overwhelmed.

In an unprecedented move, he left the country without saying either that he was leaving or where he was going. It was a startling turn of events and for a day or two the students and workers thought they had won.

But Mr. de Gaulle returned, dissolved the National Assembly and called an election for the end of June. Already, on May 27, the government and the unions had made a deal to get the striking workers back on the job, offering them generous pay increases and benefits.

But the established hierarchy and formality that permeated relationships between teachers and students, parents and children, bosses and workers, and ultimately even politicians and citizens, had been upended.

“At the level of daily life, and the relationships of people with institutions, there were big changes,” said Mr. Queysanne, the professor of the philosophy of architecture.

When students returned to classes, they could now ask questions in class and dispute ideas — a revolution in the French educational system. Bosses had to treat their workers better.

But that heady atmosphere of social foment, excitement and a sense of deep camaraderie that cut across class and education, that touched factory workers, students, intellectuals and farmers alike had passed.

There would be other moments of social protests, but none that were quite the same as those that occurred in the Paris spring of 1968.

During the major strikes and student uprisings in France that year, the École des Beaux-Arts turned itself into a workshop for revolutionary messages.

By Alissa J. Rubin May 4, 2018

PARIS — Fifty years ago, almost to the day, students here began to strike over the rigidity and hierarchy of the French university system, defying the historical deference of young people to their elders; the same day, workers at a major factory near Nantes walked out.

Within days, the strikes spread to other universities and factories, and garbage collectors and office workers joined in. By mid-May, more than 10 million people across France were on strike, and the country had all but come to a standstill.

The protests of 1968 ushered in more than five years of social upheaval, intensifying an antiwar movement in Europe and contributing to the women’s liberation and gay rights movements. And it all started with a call to upend the old order.

“There was an idea that France was a class society and it had to be torn down,” said Éric de Chassey, a professor of contemporary art who curated, with Philippe Artières, “Clash of Images,” an exhibition at the Beaux-Arts de Paris. It showcases posters from those early days of social upheaval, as well as art and documents from subsequent protests for women’s rights and gay rights.

The show’s title refers to the way the 1968 protests evolved from uniting the left and people from different backgrounds — middle class and working class — to dividing them when the strikes ended and leftist factions re-emerged. But in those first months of protest, university students, factory workers and government employees joined intellectualsand teachers to try to fulfill the dream of making France a more egalitarian place.

The École des Beaux-Arts was at the center of the revolt. Many of the prestigious art school’s students and teachers occupied the 300-year-old stone structure on the Left Bank of the Seine: Rather than holding meetings only in the building’s vast rooms and courtyards, they turned the school into an atelier, or artists’ workshop, where they created protest art.The often arresting posters straddled the line between art and propaganda.

“Someone would say ‘We need a poster that talks about immigration,’ ” Mr. de Chassey explained. “Then someone would propose a design, someone else would propose a slogan and then it would be discussed by a committee.”

The students printed hundreds or sometimes several thousand copies of the posters and taped them to lampposts and walls around Paris. In an era before the internet, the posters became a trusted way to communicate plans for action as well as the protesters’ political messages. There was little faith in electronic media at the time because it was state owned.

The strikes that began in May 1968 became the template for social protest in contemporary France, and although the fervent anti-establishment sentiments have faded, the mentality of struggle still resonates. The Beaux-Arts posters, on display through May 20, give a sense of the ferment of idealism, rebellion and rejection of the status quo that permeated French society and marked the second half of the 20th century.

Some of the posters are easily comprehensible, but others need a little explanation. Here’s a look at 11 of the most emblematic.

One of the most iconic posters on display depicts a member of the French riot police (the Compagnies Républicaines de Sécurité, or C.R.S.) as a baton-wielding member of the SS, the Nazi special police.

Under the title “Grève Illimitée” (“Unlimited Strikes”), three figures walk arm in arm, representing the students, union members and factory workers who joined together in protest.

The words on a bottle of poison read, “Press Do Not Swallow,” a warning not to trust the state-owned news media. At the time, France’s television and radio stations were state-owned corporations.

The raised fist is a straightforward call to march and to fight for the causes of students and workers. It remains a well-known symbol of solidarity on the left.

Police officers raided the École des Beaux-Arts and forcibly expelled the students who had occupied it, turning the complex into a workshop. In this poster, a helmeted officer, complete with wolf-sharp teeth, grips a paintbrush in his mouth, a symbol of the police takeover of the school.The slogan plays on the French verb “afficher,” which means “to display” but in its reflexive form, “s’afficher,” means “to show up.” The poster says: “The police show up at the Beaux-Arts, the Beaux-Arts displays in the street.”

The poster above is a straightforward reference to the ties that bond factory workers and university students and that calls on them to unite.

This poster shows the silhouette of Charles de Gaulle, a World War II general and the French president at the time, covering the mouth of a young man. “Be young and shut up,” he says. The expression was also an adaptation of a well-known phrase, sometimes used to denounce sexism, from a popular French film of 1958 titled “Be Beautiful but Shut Up.”

A sketch of Daniel Cohn-Bendit, a French-German student leader during the uprising, above the French words for “We are all undesirables.” It refers to Mr. Cohn-Bendit’s expulsion from France during the protests, when he was deemed “an undesirable.”

In this poster, the factory chimney completes the last letter of “Oui,” or “Yes,” above the words “Occupied factories,” to encourage workers to take over more of them. At the time, factories all over France were closed or occupied by striking workers. Among the many companies affected were the auto manufacturers Renault and Citroën, and the aeronautics firms Sud Aviation and Dassault.

In response to the protests, Mr. de Gaulle was reported to have said: “Reform, yes. Havoc, no.” The poster above reads “Once again, the havoc is him.” Until 1968, Mr. de Gaulle was primarily associated with the resistance in World War II, but in ’68 he tried to repress the strikes with armed police officers. His lack of sympathy for the strikers and his seeming inability to understand them made him the target of much of the protesters’ anger.

This classic poster of May ’68 depicts unity between French and immigrant workers. France had recruited many workers from Algeria, Morocco and Tunisia to help build railroads and other infrastructure or industrial installations. A short man, who appears to symbolize the factory owners or owners of capital, tries to push them apart. The slogan reads, “Workers united.”

Daphné Anglès contributed reporting from Paris.