… remember in this country of yours that every man, woman and child who sees you will remember it with joy – remember it in the words of that 17th century poet who wrote these lines, “I did but see her passing by and yet I’ll love her till I die”.

Australian Prime Minister Sir Robert Menzies to Queen Elizabeth, Melbourne, 1963.

Watching a coronation is the constitutional equivalent of visiting a zoo, and finding a Triceratops in one of the enclosures.

British historian Tom Holland

The United Kingdom is alone in Europe in marking the accession of a new monarch with a coronation. Indeed, no monarchy can lay claim to a longer lineage – one reaching back it is said to the Bronze Age and rooted in history and religion, and also magic and superstition. Inside Westminster Abbey, audiences will be encouraged to follow six phases of what is essentially a medieval rite, some of it dating back to Anglo-Saxon kingship: the recognition, oath, anointing, investiture (which includes the crowning), enthronement and homage. Britain is indeed the only European monarchy to retain a religious ceremony.

So, anyone expecting that the upcoming coronation of King Charles III and Queen Camilla would be a thoroughly modern affair suited to the 21st Century is likely to be disappointed.

One significant innovation, however, is that millions of other Commonwealth citizens attending coronation events and watching on television will be asked to cry out and swear allegiance to the King with the public given an active role in the ancient ceremony for the first time in history.

King Charles III’s coronation service – the first for a British monarch in 70 years – has been modernised to include the first-ever Homage of the People and will also include faith leaders from Jewish, Hindu, Sikh, Muslim and Buddhist communities to better represent the make-up of modern Commonwealth countries. A new homage was written to allow “a chorus of millions of voices” to be “enabled for the first time in history to participate in this solemn and joyful moment”, Lambeth Palace – the office of the Archbishop, announced. The Archbishop of Canterbury will call upon “all persons of goodwill in The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, and of the other Realms and the Territories to make their homage, in heart and voice, to their undoubted King, defender of all … a great cry around the nation and around the world of support for the King” from those watching on television, online or gathered in the open air at big screens.

…. our strength in ages past

As these two highly entertaining and most informative articles makes clear, whilst the guest list is much shorter than that of past right royal enthronements, in the interests of public health bad safety, we are told. There will be no silk stockings and knee breeches for the King or any of the peerage; the number The length of the ceremony has been shortened, for economy and impatient news cycle. The banquets and street parties have been exhorted to eat quiche, a nod to HM’s vegetarianism. The old times are by no means a’changin’. But, rites and rituals historically and hysterically archaic and arcane will prevail as will the imprimatur of the deity, the unctuous sanction of the demographically diminished Church of England and the rights and privileges of the theoretically hereditary aristocracy are upheld in time-honoured, anachronistic fashion.

The first is written by Australian constitutional expert Anne Twomey who has taken time off from her busy day-job explaining defending the coming referendum on the Indigenous and Torres Strait Island Voice to Parliament. the second, by Observer columnist Catherine Bennett describes the amazing and unforetold apotheosis of soon to be Queen Camilla, Charle’s longtime paramour.

But first, a brief forward from celebrated/celebrity Anglo-Australian barrister and author Geoffrey Robertson. He is no fan of royalty, and is possessed of a sharp pen and a wit to match:

“In London, plans for the coronation of the King and Queen of Australia proceed apace. The ceremony is entirely unnecessary because Charles has been our lawful king from the moment of his mother’s death. This event has no meaning in law; it is merely a superstitious rite whereby God is supposed to anoint the King to run the Church of England, a church to which, according to our last census, only 9.8 per cent of Australians adhere. [Indeed, some 40% of Britain’s profess to having no religion, whilst Christianity accounts for a large diminishing proportion of believers in a celestial deity]

Meanwhile, down under …

On Saturday, when the Archbishop of Canterbury conducts the coronation at Westminster Abbey, he will not just be crowning Charles as the King of England, but the King of Australia as well – though we Aussies will not be granted a three day holiday for the occasion like our British cousins.

When the late Queen was crowned in 1953, she promised “to govern the peoples of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, the Union of South Africa, Pakistan and Ceylon, and of [Her] Possessions and the other Territories to any of them belonging or pertaining, according to their respective laws and customs”. These were the nations which at the time were British dominions, and constituted what is still called “the Realm”, i.e. the countries which recognised the sovereign as their head of state.

The words of the coronation oath that Charles will take are briefer. As there are now 15 Realm nations (of which Australia is one), it has been decided not to list them all individually. His majesty’s promise will be to govern “the Peoples of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, [His] other Realms and the Territories to any of them belonging or pertaining”.

And thereafter, to reprise, we will be exhorted to pledge homage “in heart and voice, to our undoubted King, defender of all … “

On matters monarchical, read also in In That Howling Infinite, The Crown – the view from Down Under; Beyond Wolf Hall (1) – Revolution Road, Beyond Wolf Hall (2) – Icarus ascending, and Bringing it all back home – the missing mosaic and other ‘stolen’ stuff

Expect arcane pomp during King Charles III’s coronation

Anne Twomey, The Weekend Australian, 22nd April 2023

The right to brandish a wand, bear a golden spur or produce a right-handed scarlet glove is more likely to conjure associations with Hogwarts than Westminster Abbey. Yet these rights have been bitterly fought over by British families for centuries, leading to a tense wait for the email summons to fulfil their dynastic destinies at the upcoming coronation.

For King Charles III, it will be quite the dilemma. Does he cut out the historical rights and duties of ancient British families to perform particular services at the coronation, such as the King’s Champion, so he can present a modern, relevant monarchy to the world? Or would doing so set the monarchy adrift from the history that justifies its existence?

It seems he is taking a halfway approach, with some of the eccentric pomp and drama surviving, while other roles have been swept away into the dustpan of history.

The golden spurs

One of the most fought-over roles has been to carry the golden spurs and present them to the King, touching them against his ankles.

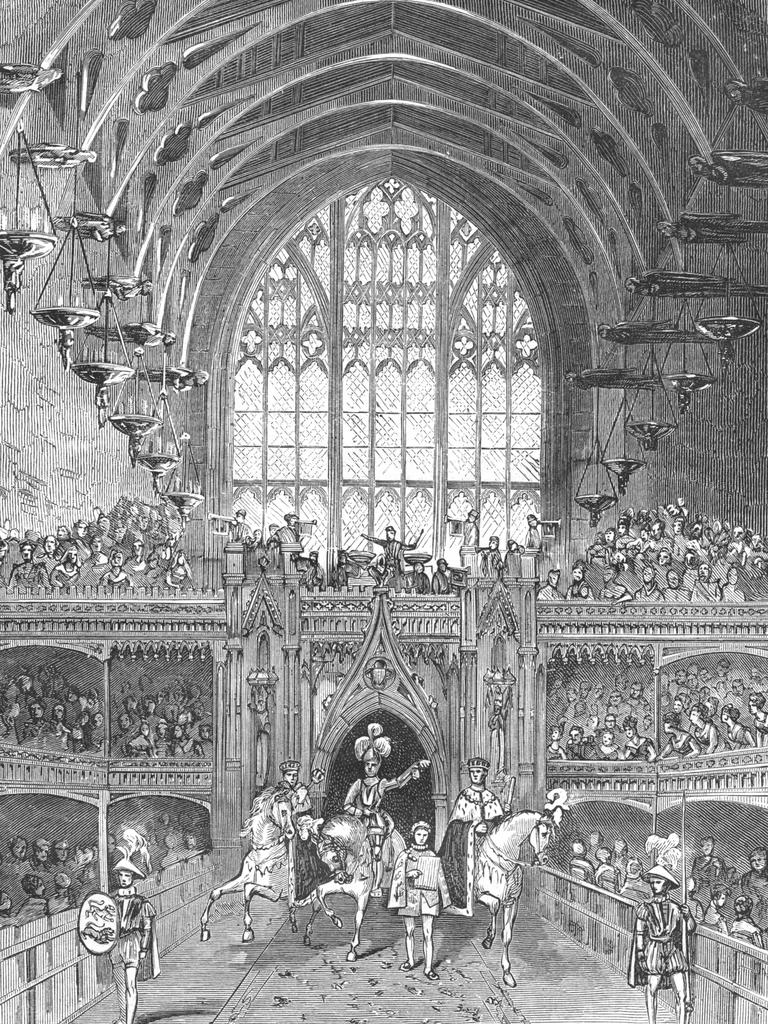

Spurs were first presented at the coronation of Richard the Lionheart at Westminster Abbey on September 3, 1189. They symbolised his chivalry and his valour as a knight. John Marshal was accorded the honour of presenting them, and this honour has been passed down to his descendants.

The chronicler of Richard’s coronation recorded that there were “evil omens” at the service, including a bat that swooped around the king during the ceremony and a mysterious pealing of bells. Richard survived another decade until dying from battle wounds in 1199.

But the evil omen may have attached itself to the bearer of the spurs, as his line of descendants was sometimes disrupted, with one heir suffering summary execution after having been accused of sorcery in the 14th century and another being killed in a tournament. Second marriages and failures to produce male heirs resulted in disputes about which branch of the family had inherited its coronation rights.

In the 19th century, the role was dominated by the redoubtable Barbara, Baroness Grey de Ruthyn, a notable fossil collector and geologist, who carried the spurs with aplomb at the coronations of George IV, William IV and Queen Victoria. But her two marriages and a surfeit of daughters who were co-heirs led to a messy chain of inheritance, with four families fighting for the coronation honour ever since.

These disputes were resolved before each coronation by a court of claims, where barristers armed with large scrolls of family trees would battle it out before eminent judges. In 1902, the court held that none of the three claimants had proved their right to carry the spurs at the coronation of Edward VII, and left it to the king to decide. He diplomatically decided that Baron Grey de Ruthyn could carry one spur and the Earl of Loudoun could carry the other. The same division was applied at the coronation of George V.