In This Is What It Looks Like, published very soon after the Bondi Beach massacre, we wrote:

“Facebook fills with empathetic words and memes from politicians, public figures and keyboard activists who spent the past two years condemning Israel in ways that blurred – and often erased – the distinction between Israeli policy and Jewish existence, creating at best, indifference to Jewish fear and, at worst, a permissive climate of hostility toward Jews as such. Today it is all tolerance, inclusivity and unity – and an air of regret and reverence that reeks of guilt.

But not all. Social media has fractured along familiar lines. At one extreme are conspiracy theories — false flags, invented victims, claims the attackers were Israeli soldiers. At the other is denial: what antisemitism? Between them sits a more revealing response. There is genuine shock and horror, even remorse – but also a careful foregrounding of the Syrian-Australian man who intervened, coupled with a quiet erasure of the victims’ Jewishness; a reflexive turn to whataboutism; and a refusal, even now, to relinquish the slogans and moral habits of the past two years. If antisemitism is acknowledged at all, it is ultimately laid at the feet of Israeli prime minister Binyamin Netanyahu.

Why this reticence, we asked, this resistance to reassessment after the Bondi attack? Perhaps it lay less in ideology than in psychology. For some, was there is a simple inability to relinquish prior convictions – positions publicly held, repeatedly performed, and now too entangled with identity to abandon without cost. For others, was it perhaps a deeper reluctance to acknowledge having been misinformed or misdirected, an admission that would require not just intellectual correction but moral self-reckoning? Was it that empath has become selective: extending it fully to Jewish victims would require suspending, even briefly, a framework that collapses Jewish identity into the actions of the Israeli state. And finally, we asked whether many were no longer reasoning freely at all, but are caught inside the machinery – the rhythms of platforms, slogans, group loyalties and algorithmic reinforcement – where reconsideration feels like betrayal and pause feels like capitulation.

Indeed, since October 7, 2023, In That Howling Infinite has pondered why erstwhile liberal, humanistic, progressive people from all walks of life have been caught up in what can be without subtly described as that anti-Israel machinery referred to above in which opposition at a safe distance to what is seen as Netanyahu’s genocidal Gaza war has seen professed anti-Zionism entangled with anti-Semitism.

What we are witnessing is not a fringe radicalisation but a moral capture: people who would once have prided themselves on scepticism, nuance and historical memory now moving in formation, repeating slogans whose lineage they neither examine nor recognise. The machinery works precisely because it flatters their self-image. It offers the intoxication of righteousness without the burden of precision; solidarity without responsibility; protest without consequence.

This is not old-style antisemitism with its crude caricatures and biological myths. It is something more elusive – and therefore more powerful. It presents itself as ethics, as international law, as human rights discourse scrubbed clean of Jewish history. Israel becomes not a state among states but a symbol onto which every colonial sin can be projected. Complexity is treated as evasion; context as complicity. The very habits of mind that once defined liberal humanism – distinction, proportion, tragic awareness – are recoded as moral failure.

And because the animating energy is moral rather than ethnic, many participants genuinely believe themselves immune to antisemitism. They do not hate Jews; they merely deny Jews the one thing liberalism once insisted all peoples possess: the right to historical contingency, to imperfect self-determination, to moral fallibility without metaphysical damnation. That is how an ancient prejudice survives under a modern flag.

What makes this moment particularly dangerous is that the capture extends across institutions that once acted as guide rails and backstops: universities, cultural organisations, media, NGOs, even parts of the political class. When the liberal centre internalises a narrative, it no longer needs coercion; it polices itself. Silence becomes virtue. Dissent becomes indecency. The boundaries of acceptable speech narrow – not by law, but by moral shaming.

This is why inquiries and commissions feel inadequate, even faintly beside the point. The problem is not that we do not know enough. It is that too many people who should know better have decided – consciously or otherwise – that some falsehoods are useful, some hatreds understandable, some erasures permissible.

History suggests these moments do not end because facts finally win an argument. They end when enough people recover the nerve to say: this is not true, this is not proportionate, this is not who we are. That requires intellectual courage before it requires policy – and at the moment, courage is in shorter supply than outrage.

What, then, do we actually mean by moral capture?

An intellectual box canyon

It describes a condition in which an individual or group becomes psychologically, socially, and culturally enclosed within a moral framework so totalising that it can no longer be revised or questioned without threatening their sense of self. It is best understood not as a theory, still less as a conscious posture, but as a lived and almost tangible condition: a quiet enclosure of mind and conscience in which questioning the framework feels not merely wrong, but personally destabilising. It is not simply ideology or prejudice, but a subtle narrowing of moral imagination—a shaping of what can be felt, what can be said, and ultimately, what can be seen.

Under moral capture, empathy becomes conditional. It travels only so far before it threatens the moral story we have already committed to, the narrative through which we recognise ourselves as good. Judgement is no longer exercised independently but is subordinated to alignment. We begin thinking from conclusions rather than reasoning toward them, measuring the world not against principle but against the positions we have already staked as right. Certain conclusions feel self-evident; certain questions become illegitimate; doubt itself starts to register as moral weakness rather than intellectual honesty.

Positions once held as views harden into identity, reinforced by social approval, public performance, and the feedback loops of online life. People can feel sincere, committed, and righteous even as their capacity to notice contradiction, hold tension, or revise belief steadily diminishes. What is lost is not feeling, but freedom—the freedom to think, to hesitate, and to change one’s mind.

In a phrase, moral capture is an intellectual box canyon: wide at the entrance, reassuringly coherent and morally clear once inside, but increasingly difficult to exit without retracing your steps

Our moral choices, once optional, become invested in our identity. What we once held as a conviction now defines us, fuses with our sense of self, our social belonging, our reputation. And habits reinforce themselves. Ritualised moral performances, applause from peers, and the accelerating feedback of online platforms harden the framework, making reconsideration feel not just difficult, but almost impossible.

In this state, otherwise humane, intelligent people can feel virtuous, committed, and righteous while the breadth of their moral imagination steadily narrows. Certain truths -even the most visible – become unsayable. Empathy grows selective. The unthinkable becomes thinkable, so long as it fits the story our framework allows.

This essay is my attempt to explore moral capture as it happens in real time: to see how it shapes our response to atrocity, how it bends grief and outrage, and why even shock – when filtered through these habits – becomes partial, provisional, and fragile.

Conditional empathy and the failure of shock

In That Howling Infinite did not begin thinking about moral capture because it was looking for a new explanatory framework, nor because it believed itself morally exempt from the currents of the moment. Rather, because in the aftermath of the Bondi atrocity something felt profoundly unsettled – not only tragic, but discordant. The language of grief arrived swiftly and abundantly. Condolences were offered, candles lit, unity invoked. And yet this display sat uneasily alongside two years of rhetoric in which Jewish fear had been minimised, relativised, or quietly absorbed into a moral narrative that treated Israel not as a state among others, but as a singular moral contaminant.

What was disturbing was not the outrage directed at Gaza. The suffering there is real, appalling, and morally unavoidable. Israel’s retaliation has been devastating and, in many instances, disproportionate. Reasonable people can, and must, grapple with that reality. What was troubling was how easily that outrage had slid, over time, into habits of thought that blurred distinctions which once mattered: between state and people, policy and identity, criticism and contempt. The taboo on antisemitism, long assumed to be settled history, began to look less like a moral achievement than a conditional courtesy.

After Bondi, we did not expect a mass moral conversion or imagine that people who had spent two years publicly performing righteous indignation would suddenly execute a full reversal – a neat return to complexity, restraint and tragic awareness. That would have been unrealistic, perhaps even unfair. What we did expect, and hoped for, was hesitation. A pause. A moment of reassessment. An acknowledgement, however tentative, that something in the moral atmosphere had gone wrong.

Instead, what emerged was something more revealing: grief without revision; empathy carefully bounded; sorrow hedged with qualifications. The familiar “Ah, but…” arrived almost on cue. It was there, in that reflex, that we began to see the outline of a deeper phenomenon – not simple prejudice, not even ideology, but moral capture.

Moral capture occurs when a moral framework that once helped organise reality becomes totalising – so emotionally, socially and symbolically reinforced that it can no longer be revised without threatening the self who holds it. At that point, facts do not merely challenge the framework; they imperil identity. And when identity is at stake, reason quietly steps aside.

One of the clearest signs of moral capture is the collapse of distinctions. Israeli policy becomes Jewish existence. Jewish fear becomes political theatre. Antisemitism becomes a rhetorical device wielded by Benjamin Netanyahu. Violence against Jews becomes, if not justified, then contextualised into moral thinness. Language flattens. Precision feels like evasion. Context is treated as complicity.

This helps explain the strange choreography of response after Bondi. There was genuine shock and sorrow, even remorse. But it was accompanied by careful editorial choices: the foregrounding of a heroic rescuer, the quiet erasure of the victims’ Jewishness, the reflexive turn to whataboutism, the insistence – sometimes whispered, sometimes explicit – that responsibility lay elsewhere. Jewish suffering could be acknowledged only insofar as it did not demand a reckoning with the moral habits of the past two years.

Why this resistance? Part of the answer lies in identity as investment. For many on the modern left, opposition to Israel has not remained a policy position; it has hardened into a moral identity, publicly performed, socially rewarded, and algorithmically amplified. Positions once adopted as expressions of concern or solidarity have become entangled with one’s sense of self -who one is, where one belongs, what one signals to the world. To revise those positions now would involve not merely intellectual correction, but moral self-reckoning: admitting error, acknowledging harm, risking social alienation. That is a price most people instinctively avoid.

Solidarity, under these conditions, mutates into surrender. The capacity to stand with the vulnerable while retaining independent moral judgement is lost. Complexity becomes betrayal. Reassessment becomes cowardice. To pause is to hesitate; to hesitate is to defect. Moral reasoning gives way to moral alignment.

This process is intensified by platforms that act as algorithmic accelerants. Social media does not reward reflection; it rewards repetition with conviction. Moral language becomes compressed into slogans. Outrage is incentivised; nuance is penalised. Over time, people cease reasoning toward conclusions and begin reasoning from them. The machinery does the rest. Group loyalty replaces judgement. Reconsideration feels like capitulation.

In this environment, antisemitism does not need to announce itself. It seeps. It jokes. It chants. It flatters those who believe they are on the right side of history by assuring them that their anger is justice and their certainty courage. The world’s oldest hatred does what it has always done: it waits for permission. That permission is rarely granted all at once. It is granted gradually, rhetorically, respectably.

This is why Bondi did not “break the spell.” Atrocities shock only when the moral framework remains flexible enough to absorb them. Here, the framework was already closed. Violence could be mourned, but not allowed to destabilise the story that preceded it. Empathy could be expressed, but only within boundaries that preserved moral coherence. Jewish fear remained an inconvenience—something to be managed, not centred.

The habituation of moral capture meant that grief was permitted only insofar as it did not demand reassessment. Empathy was bounded, sorrow hedged, and moral recognition carefully staged. Those who might have been shocked into reflection instead performed selective empathy, affirming the gestures of mourning while leaving the architecture of two years of moral habit intact

Throughout this exploration, In That Howling Infinite asked myself an uncomfortable question: do we lack the empathy and outrage that others so visibly express? Are we insufficiently moved? Insufficiently angry? We do not think so. Though saddened by Gaza and angered by unnecessary suffering, it is appalled by violence against Jews. What differs, perhaps, is not the presence of feeling but the habits through which it is processed. It’s background, sensibility and experience incline it toward holding multiple truths in tension – to see, as the song has it, the whole of the moon. That does not make it wiser, only more resistant to moral monoculture.

Moral capture is powerful precisely because it allows people to remain good in their own eyes while surrendering the disciplines that once made goodness durable. It does not feel like hatred. It feels like justice. It does not announce itself as intolerance. It presents as virtue.

What we have learned on this journey is not that outrage is illegitimate, nor that empathy must be rationed. It is that empathy becomes dangerous when it is conditional; that solidarity curdles when it demands surrender; and that moral frameworks, once weaponised against reconsideration, eventually turn on the very values they claim to defend.

History does not ask whether our intentions were pure. It asks what we normalised, what we tolerated, and what we allowed to be said in our name. Moral capture works hardest to ensure we never ask those questions of ourselves. The task now is not to abandon conviction, but to recover freedom it the freedom to doubt our own righteousness, to let empathy travel where it is inconvenient, and to remember that seeing only half the sky is not the same as moral clarity.

Only then do we begin to see the whole of the moon.

In That Howling Infinite December 2025

Author’s note …

This opinion piece is one of several on the the attitudes of progressives towards the Israel, Palestine and the Gaza war. Shaping facts to feelings – debating intellectual dishonesty– regarding the Gaza war, intellectual dishonesty is everywhere, on both sides of the divide, magnified by mainstream and social media’s hunger for moral simplicity and viral outrage. Standing on the high moral ground is hard work! discusses the issues of free speech and “cancellation”, and boycotts with regard to the recent self-implosion of the Adelaide Writers’ Festival, one of the country’s oldest and most revered.

There are moments when public argument stops being a search for truth and becomes a test of belonging. Facts are no longer weighed so much as auditioned; empathy is rationed; moral language hardens into a badge system, issued and revoked according to rules everyone seems to know but few are willing to articulate. One learns quickly where the trip-wires are, which sympathies are permitted, which questions are suspect, and how easily tone can outweigh substance.

What interests me here is not the quarrel itself – names, borders, histories—but the habits of mind it exposes. The ease with which conviction can slide into choreography. The way intellectual honesty is praised in the abstract and punished in practice. The curious transformation of empathy from a human reflex into a conditional licence, granted only after the correct declarations have been made.

Across these pieces I circle the same uneasy terrain: the shaping of facts to fit feelings; the capture of moral language by ideological gravity; the performance of righteousness as both shield and weapon. Cultural spaces that once prided themselves on curiosity begin to resemble courts, where innocence and guilt are presumed in advance and the labour lies not in thinking, but in signalling.

This is not an argument against passion, nor a plea for bloodless neutrality. It is, rather, a meditation on how quickly moral seriousness curdles into moral certainty – and how much intellectual work is required to stand on what we like to call the high ground without mistaking altitude for clarity.

The position of In That Howling Infinite with regard to Palestine, israel and the Gaza war is neither declarative nor devotional; it is diagnostic. Inclined – by background, sensibility, and experience – to hold multiple truths in tension, to see, as the song has it, the whole of the moon. It is less interested in arriving at purity than in resisting moral monoculture and the consolations of certainty. That disposition does not claim wisdom; it claims only a refusal to outsource judgment or to accept unanimity as a proxy for truth.

On Zionism, it treats it not as a slogan but as a historical fact with moral weight: the assertion – hard-won, contingent, imperfect – that Jews are entitled to collective political existence on the same terms as other peoples. According to this definition, this blog is Zionist. It is not interested in laundering Israeli policy, still less in romanticising state power, but rejects the sleight of hand by which Israel’s existence is transformed from a political reality into a metaphysical crime. Zionism is not sacred, but its delegitimisation is revealing – because it demands from Jews what is demanded of no other nation: justification for being.

On anti-Zionism, it has been unsparing. It sees it not as “criticism of Israel” (which you regard as both legitimate and necessary) but as a categorical refusal to accept Jewish collective self-determination. What troubles it most is not its anger but its certainty: its moral absolutism, its indifference to history, its willingness to borrow the language of justice to license erasure. It is attentive to how anti-Zionism recycles older antisemitic patterns – collectivisation of guilt, inversion of victimhood, and the portrayal of Jews as uniquely malignant actors – while insisting, with studied innocence, that none of this concerns Jews at all. If not outright antisemitism, the line separating it from anti-Zionism is wafer—thin, and too often crosses over.

The interest in moral capture is analytical rather than accusatory. It is not arguing that writers, academics, or institutions are malicious; rather, it are argues that they have become intellectually narrowed by the desire to belong to the “right side of history.” Moral capture explains how good intentions curdle into dogma, how solidarity becomes performative, and how the fear of social exile replaces the discipline of thought. It accounts for the strange phenomenon whereby intelligent people outsource their moral judgment to slogans, and experience constraint not as an intolerable injury to the self.

The Adelaide Writers’ Festival affairis seen not primarily about Randa Abdel-Fattah, nor even about free speech. It is a case study in institutional failure and cultural self-deception. The mass withdrawals are viewed not as acts of courage or principle but as gestures of affiliation – ritualised displays of virtue by people largely untouched by the substance of the dispute. What is disturbing is the asymmetry: the speed with which a festival collapsed to defend eliminationist rhetoric, and the silence that greeted the doxxing, intimidation, and quiet cancellation of Jewish writers and artists. Adelaide did not fall because standards were enforced, but because those standards were applied selectively and then disowned at the first sign of reputational discomfort.

Running through all of this is a consistent stance: a resistance to moral theatre, an impatience with historical amnesia, and a belief that intellectual honesty requires limits – on language, on fantasy, and on the indulgent belief that one’s own righteousness exempts one from consequence.

We are not asking culture to choose sides; you are asking it to recover judgment

.See in In That Howling Infinite, A Political World – Thoughts and Themes, and A Middle East Miscellany. and also: This Is What It Looks Like, “You want it darker?” … Gaza and the devil that never went away … , How the jihadi tail wags the leftist dog, The Shoah and America’s Shame – Ken Burns’ sorrowful masterpiece, and Little Sir Hugh – Old England’s Jewish Question

Looking for the “good Jews”

In This Is What It Looks Like, we wrote: “… antisemitism does not arrive announcing itself. It seeps. It jokes. It chants. It flatters those who believe they are on the right side of history, until history arrives and asks what they tolerated in its name”.

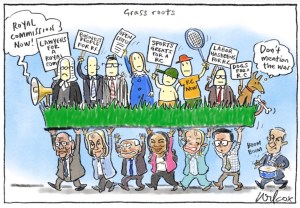

One of those jokes landed, flatly, on January 7 when the otherwise circumspect Age and Sydney Morning Herald published a caricature drawn by the award-winning cartoonist Cathy Wilcox. It presented those calling for a forthcoming royal commission into antisemitism as naïve participants in a hierarchy of manipulation. At the surface were the petitioners themselves; beneath them senior Coalition figures – Sussan Ley, Jacinta Nampijinpa Price, John Howard, David Littleproud – alongside Rupert Murdoch and Jillian Siegel, lawyer, businesswoman and Australia’s Special Envoy to Combat Antisemitism; and behind them all, setting the rhythm, Israel’s prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu. Each layer marched to a beat not its own.

Cathy Wilcox cartoon, SMH 7 January 2026

Critics argued that the image revived a familiar and corrosive trope: the suggestion of hidden Jewish influence directing political life from the shadows. The cartoon, titled Grass roots, depicts a cluster of foolish-looking figures demanding a royal commission. They are presumably meant to represent the families of the dead, as well as lawyers, judges, business leaders and sporting figures who had urged government action long before the Prime Minister concluded that continued indifference might stain his legacy. When he finally announced a royal commission—expanded, without explanation, to include the elastic phrase “social cohesion”—no journalist paused to ask what that addition was meant to clarify.

In the drawing, a dog stands among these Australians, holding a placard and thinking, “Don’t mention the war.” The grass beneath their feet is supported by a menacing cast: and stock villains of the anti-Zionist imagination. The implication is unmistakable: that the pleas of grieving families and prominent citizens are neither organic nor sincere, but choreographed – another performance conducted from afar.

That implication did not arise in isolation. Across social and mainstream media, many progressives called for Jillian Segal to be removed and her report rejected out of hand. Others elevated Jewish critics of the war, of Zionism, or of Netanyahu as moral exemplars – “good Jews,” “some Jews tell the truth” – as if Jewish legitimacy were contingent on ideological alignment. Some wrote openly that Jews, “for their numbers,” exercised excessive influence. One circulating meme complained, “We didn’t vote for a Zionist voice”, whilst other posts informed their echo chamber that Chabad Bondi, a branch of the global Jewish outreach organisation, which had organised the Hanukkah gathering on the fateful Sunday evening and also the local commemorations for the victims (and later, the tribute at the Sydney Opera House) was but another tentacle of the sinister and uber-influential Jewish Lobby. Some of the most incongruous postings have been of ultra Orthodox Jews – Haredim – with signs condemning the Gaza war and Zionism, as if to say these are the authentic, “good” Jews. Some footage actually shows Haredim protesting against the Israeli government’s efforts to conscript exempt yeshiva students into the IDF – but, as they say, every picture tells a story.

Running beneath this was a persistent misconception. Judaism was treated as a religion, detachable and voluntary, rather than as an ethnoreligious identity shaped by lineage, memory and shared fate. Jews were asked not simply to oppose Israeli policy but to renounce their “homeland,” their inheritance, their sense of collective belonging. Census figures were deployed to minimise Jewish presence, overlooking the fact that many Jews, with Germany in the 1930s still in mind, remain reluctant to advertise religious affiliation. Genealogical platforms tell a different story: the number of people who discover Jewish ancestry far exceeds those who publicly profess the faith.

Another factor further clouds understanding. Jews are rarely dogmatically regarded as part of what Australians loosely call our “multicultural” society – a variegated demographic more often reserved for the post–White Australia waves of migration – communities that are visibly non-European or culturally distinct. Jews slipped beneath that radar. Many arrived well before the Second World War, and those who came before and after tended to integrate, to go mainstream, to succeed, and therefore not to stand out.

As a result, Jews were quietly folded into an older Judeo-Christian demographic, grouped alongside Protestants and Catholics as part of the cultural furniture rather than recognised as a minority with a distinct history and vulnerability. In most urban, and even regional settings, many Australians would be unaware that Jewish families live among them at all. At the same time, a surprising number of people carry Jewish ancestry several generations back, or are connected through marriage or descent, without regarding this as identity in any conscious way.

This invisibility cuts both ways. It has allowed Jews to belong without friction, but it has also made Jewishness strangely abstract – easy to misclassify as belief rather than continuity, easy to overlook as lived experience, and easy, when political passions rise, to treat as conditional.

Here the paradox sharpens, particularly among progressives. There is genuine respect for Indigenous Australians’ reverence for history, genealogy and Country: an understanding that identity is inherited as much as chosen, that land carries memory and obligation across generations. Yet the Jewish connection to Zion is denied that same conceptual dignity. What is recognised as ancestral continuity in one case is dismissed in the other as theology, nationalism or ideology.

The inconsistency is telling. Jewish attachment to place is stripped of its historical depth and cultural persistence, judged by standards not applied elsewhere. In that light, the cartoon does more than offend. It gives visual form to a deeper habit of thought: one that sorts Jews into acceptable and unacceptable categories, organic grief and foreign orchestration, legitimate belonging and suspect attachment- depending on who is being asked to explain themselves, and to whom.

All of this helps to explain the dangerous and disturbing upsurge in antisemitism over the past two years and earlier.

The Bondi massacre did not invent anti-Semitism in Australia; it exposed a system already bent, quietly, against seeing it. Two recent articles in The Australian show in complementary ways two faces of the same failure: one structural, one intimate. On the one hand, Professor Timothy Lynch diagnoses the intellectual and institutional blindness that allows hatred to incubate unchecked; on the other, author Lee Kofman shows the personal toll when grief itself is made conditional on passing someone else’s moral purity test. Together, they reveal a society in which moral frameworks have become cages rather than guides.

For decades, Australian multiculturalism has performed a delicate contortion: apologising for its own history while demanding loyalty from newcomers. Original British settlement is framed as a sin; multiethnic immigration is a progressive corrective. The paradox, Lynch notes, is that the very order migrants join is simultaneously denigrated by the leaders they are expected to trust. Within this structure, Jews occupy an uncomfortable space: electorally negligible, culturally visible, historically persecuted, yet paradoxically recoded as white and colonial. Zionism – a project of survival and refug e- is reframed as a form of imperial wrongdoing, while other nationalisms pass without scrutiny. Anti-Semitism, filtered through progressive identity politics, becomes an exception to the very rules designed to prevent harm.

Bondi rendered these abstract asymmetries concrete. The massacre forced recognition that anti-Semitism, once dismissed as campus rhetoric or aestheticised resistance, could and would become lethal. Lynch observes that progressive moral frameworks – micro-aggressions monitored, systemic racism theorised -stop precisely at the Jew. A royal commission, he argues, would not be vindictive; it would be a sober exercise in moral clarity, tracing the cultural and ideological currents that incubated violence. Yet the same cultural institutions that produced those currents remain invested in their own innocence, framing ideas as harmless discourse even as they provide tacit validation for hatred.

Kofman brings this insight down to the level of lived experience. Her grief, initially raw and private, became a public transaction. Condolences were offered, often, with moral caveats: critique Israel just so, moderate outrage, avoid triggering Islamophobia, defer to “Good Jews” as intermediaries for acceptable mourning. Grief, she realised, was conditional: to mourn fully, one had to pass a moral test. She claimed her place among the Bad Jews – those attached to ancestral lands, critical yet loyal, unbowed by external sensibilities. In doing so, she and others began to speak publicly, reclaiming authority over their grief and over the narrative of their own people. The silver lining, Kofman suggests, lies not in filtered approval from outsiders but in the courage of authenticity: listening, amplifying, and insisting on nuance.

Both authors reveal the same systemic dynamic from different angles: moral capture. Identity has become an investment; empathy is asymmetric; ideological frameworks collapse distinctions, judging hate by its source rather than its effect. Lynch shows that structural conditions—campus rhetoric, art institutions, political taboos – render society defenseless against the incubation of lethal prejudice. Kofman shows that these same conditions turn grief into a contested commodity, rationed according to moral convenience. Bondi, in its horror, exposes the cost of these failures. The killers were here, not abroad; the culture that nurtured their hatred was domestic, familiar, and in many cases, ideologically protected.

The lesson is twofold. First, moral frameworks must be able to interrogate themselves without fear: to analyse ideas, ideologies, and cultural norms is not to endorse them. Second, grief, solidarity, and moral recognition cannot be rationed according to convenience or identity politics. True empathy – what Kofman calls listening beyond comfort zones and algorithmic echoes – requires attending to the voices of those most affected, even when they unsettle our assumptions. In other words, the antidote to moral capture is both structural and intimate: rigorous, unflinching public inquiry alongside the personal courage to honor grief unconditionally.

Bondi’s tragedy leaves no simple remedies. But by exposing the moral contradictions of multiculturalism and the conditionality of recognition, Lynch and Kofman give us a framework for reflection: a society that cannot see hate, cannot hear grief, and cannot tolerate nuance is a society poised for repetition. The challenge -and the opportunity – is to recover both: vision and voice, system and sensibility, analysis and empathy.

Chorus of ‘Bad Jews’ finds its voice: My grief is not conditional on your moral purity test

Lee Kofman, The Australian, 3 January 2026

The morning after the Bondi terror attack, I was scheduled to appear on a podcast about creativity. Going ahead with it was my way of finding that mythical oil jar which, according to Hanukkah lore, lit the Jewish people’s darkness in their hour of need.

My darkness deepened as I drove to the studio. A phone call with a friend turned into a shattering revelation. Her niece, the same age as my 10-year-old child, was murdered in Bondi. The tragedy that sat heavy in me turned visceral. Still, I drove on. I needed to be around good people. To believe in goodness.

My podcast interlocutor, another Jewish artist, seemed similarly shell-shocked. “I always look for a silver lining,” he said. “I haven’t found it yet, but I’m waiting.”

“Maybe there won’t be silver lining,” I said. The miraculous oil jar was fiction after all … We agreed to disagree, as Jews often do, ending the recording with a silent, long hug.

If only I could be so hopeful. In the days since Bondi, I have mostly felt fury and sadness. For two years, since October 7, 2023, my community has been warning that unchecked Jew-hatred – online, in weekly rallies, in cultural institutions, via the boycotting of Jewish artists, the abuse of Jewish university students and lecturers, and anti-Semitic violence – would lead to bloodshed. We had been proven right. It took 15 dead bodies for people to see what “Globalise the intifada” looks like in practice. Fifteen dead for Jewish grief and fear to finally receive public validation.

Validation was coming my way too, at first primarily from people who have supported me throughout the past two years, often at their own peril. I received dozens and dozens of moving messages of love and anguish. Was this my silver lining? Soon others arrived. Still from within my milieu – mostly left-wing, creative, non-Jewish people – but now also from those I hadn’t heard from in a long time. And from those who have contributed to normalising Jew-hatred. In certain circles, I realised, validation came with caveats. It felt as if our mourning became a subject of scrutiny, a suspect thing. Some offered condolences, then detailed the evils of Benjamin Netanyahu or guns, as if either explained (justified?) what happened.

Others, more diplomatic, sent links to videos and articles by those they regard as “Good Jews” – a handful of extreme left, anti-Zionist Jewish public figures and organisations with marginal Jewish followings, whose narratives fit those of some “progressive” milieus and are used by them as shields against accusations of anti-Semitism.

(Bad) Jewish community is overreacting again, Good Jews were saying. Anti-Semitism is as much a problem as other types of racism. Worse, (Bad) Jews are politicising the tragedy to curtail freedoms. Because the rallies with Islamist flags, promoting totalitarian political ideologies, and with chants of “all Zionists are terrorists” were peaceful and must continue. The government has done all it could; look how much money has been poured into security. Jewish organisations should hire more guards and stop celebrating events in the open, then all will be fine. Also, we should tone down our grief, to avoid encouraging Islamophobia, Good Jews suggested.

For those who sent me those later messages, I realised, my grief was conditional. To be entitled to it, I had to pass a moral test: Was I a Good or Bad Jew?

Doubtlessly, I am a Bad one. A Jew who, while opposing the current Israeli government, is deeply connected to my ancestral land, where I lived for 14 years, and to my community in Australia. A Jew unprepared to dilute her grief for somebody else’s sensibilities. A Jew holding the government and many of our cultural institutions accountable for the marginalisation, hatred and violence my people have been enduring in this country over the past two years.

Another message came through. A young journalist sent an Instagram reel in which she spoke about deciding to stop minimising her Jewishness to fit in. She’s normally a gentle person, but her words were bold, her fury palpable. I watched the video several times. I could see she was becoming Bad Jew. A badass Jew.

Soon, Bad Jews sprang up all over the place. Many who had been (understandably) fearful and quiet spoke publicly for the first time. The usually outspoken ones took things up a notch. I messaged my podcast interlocutor: “You were right. Even Bondi’s tragedy has a silver lining.” The chorus of my people was growing. The Bad Jews had spoken.

Jews are a mere 0.4 per cent of Australia’s population, not all that useful for vote-courting politicians. Unfortunately, we do not possess those powerful, all-reaching tentacles attributed to us. But we’ve always been a people of words, and our hope to survive is embedded in our willingness to use words boldly and authentically.

In recent years, Bad Jews have been pushed out of many public spheres, told it isn’t the time for our voices. (I was told this many times, especially after the publication of Ruptured: Jewish Women in Australia Reflect on Life Post-October 7, which I coedited with Tamar Paluch.) Since the Bondi massacre, however, the media has been more willing to give space to Bad Jews too.

Today I choose to be hopeful. I notice that while some non-Jews put my grief to test, more have asked how they can help. One important thing to do right now is to listen to Jewish voices, and to choose carefully who you learn from and who you amplify. To show true solidarity is to climb out of your comfort zone and algorithms. To listen to those Jews who challenge rather than confirm what you think you know about us. (Are Zionists really terrorists? Are Jews really white?)

After years of the Australian Jewish community being misunderstood and gaslit, light must be shed on our complexities and nuances. Let this be everyone’s silver lining.

This was one of five pieces published in Australian Book Review under the title “After Bondi”. Lee Kofman is the author and editor of nine books, the latest of which are The Writer Laid Bare (2022) and Ruptured (2025).

How multiculturalism chic invites violent anti-Semitism

Timothy Lynch, The Australian, 3 January, 2026

The proximate debate over a royal commission into the first mass-casualty terrorist attack on Australian soil is becoming a proxy for a larger conflict over multiculturalism.

Two camps have formed. The first, led de facto by Josh Frydenberg, demands a reckoning on how a fashionable anti-Semitism in our cultural institutions incubated the Akrams’ barbarity.

The second, led reluctantly by Anthony Albanese, who wants it all to be about guns, refuses to admit this ancient hatred has a genesis in modern progressivism. To concede any correlation, let alone a causal relationship, between the two is verboten. The multicultural project remains beyond impeachment.

The unstoppable force of Jewish Australians, post-Bondi, has met the immovable object of left-wing assumptions. The Bondi Beach crisis has exposed the jagged edges of a social experiment we are told is both ineluctable and inevitable.

Immigration as curse and cure

For decades, Australia has been trapped in a series of moral and philosophical contortions. Much of the contemporary left treats original immigration – the arrival of the British 200 years ago – as a cardinal sin. To atone, the modern progressive movement has championed multiethnic immigration as a corrective measure. This has created a paradoxical situation where the nation is required to apologise for its existence at every public event yet simultaneously expects arriving migrants to find loyalty and respect for a system, and its history, that its own leaders appear to despise.

By genuflecting and apologising for our British heritage, we weaken the system that immigrants take such risks to join. We have created a public discourse where the core of the Australian experiment is framed as something shameful, making it harder to assimilate newcomers into a positive notion of what this country represents.

We are living through the failure of the multicultural experiment to produce the social harmony its architects promised. Instead of a seamless integration, we see the exposure of small, vulnerable communities to the power of growing, noisy ones. This would put Jewish Australians at a growing disadvantage – they are electorally negligible – even before the anti-Semitism that makes them guilty by proxy of Israeli “war crimes” is factored in.

Factored in they are. Sudanese nationalist sentiment in Australia carries none of the blame for the humanitarian catastrophe that is Sudan today. But Zionism? The success of the cosmopolitan left is to turn Jewish nationalism into a form of colonial oppression.

Asymmetric multiculturalism

The only Middle Eastern state with the gender rights demanded by Australian campus progressives must be “decolonised”. When Israel acts in self-defence it commits “genocide”. Do the rainbow flags flown by our rural councils and art museums cause this? Long bow, that. Do they prevent it? No. Multiculturalism is complicit in the creation of a social order in which anything Western is regarded as suspect and anything non-Western elevated beyond its moral capacity to bear.

This has been called a form of asymmetric multiculturalism: the privileging of some peoples (usually of colour) over others (often whites). The Jews, a Semitic people, as are the Arabs, are less deserving of support because progressives have made them white and Western.

Left-wing activists have had much success convincing their peers that men can be women; we have missed how they have transitioned the Jews, the perennial victims of history, into the agents of colonial whiteness.

A tiny nation peopled mostly by those escaping the Nazi Holocaust, Soviet communism and Muslim anti-Semitism (there is no thriving Jewish minority in any Muslim-Arab state) has become the target rather than the beneficiary of liberal moralising. The profound historical illiteracy of multiculturalism, as taught in our schools and universities, has something to do with this.

None of this mattered very much to Australians until December 14, 2025. Until then, we mostly dismissed campus anti-Semitism as just what students and their lecturers do. Wasn’t the Vietnam War protested in similar terms to Gaza?

We became inured to the Israelophobic propaganda on office windows. The Palestinian flag that flies above the bookshop in Castlemaine, Victoria, flutters still – we just stopped noticing it. Let them play at “fostering a culture of resistance”. These middle-class activists weren’t complicit in the Akrams’ afternoon of resistance, were they? If you watch SBS World News regularly, you will be assured that neo-Nazis are anti-Semitic. I agree. Masked men marching annually at Ballarat mean Jewish Australians ill (and Muslims too). But the differently masked “anti-fascists” marching against Israel every Saturday afternoon? They have nothing at all to do with the creeping violence against Jews.

I don’t agree with this anymore. Not since Bondi. So-called “anti-racism” has become a prop of multiculturalists. To be anti-racist is to take inadvertent racism as indicative of a more malign form hiding in the wings. Micro-aggressions, left unchecked, will become macro-aggressions. So, police the micro diligently. I buy some of this. But why doesn’t its logic extend to the Jews?

Why do so many of the anti-Israel left refuse to connect the dots between a kippah pulled from a man’s head on a Sydney bus, the firebombing of a Melbourne synagogue and the massacre at Bondi? If the victim of each had been anything other than Jewish, we can imagine the cries of “systemic racism”.

The issue of Aboriginal deaths in custody got its own royal commission in 1987. A Labor prime minister (Bob Hawke) commissioned “a study and report upon the underlying social, cultural and legal issues behind the deaths”. The issue of Jewish deaths at Bondi Beach deserves the equivalent systemic investigation.

The liberty of distance is fading

Geoffrey Blainey argued in The Tyranny of Distance (1966) that the physical peril of emigration from Britain, under sail, meant it was a significantly male activity – leading to a deep sense of “mateship” in our social development. He has been more controversial, but not obviously incorrect, in his claim that “in recent years a small group of people has successfully snatched immigration policy from the public arena and has even placed a taboo on the discussion of vital aspects of immigration”.

The more immune to democratic discourse our immigration policies have become, the likelier an Akram or two will slip in (Sajid Akram entered on a student visa in 1998). This is not an indictment of every Muslim who contributes to the success of their chosen nation. Secular Australia provides a standard of living and a freedom of religion to immigrants, who happen to be Muslim, unmatched in the lands they leave.

Because we are physically isolated, we have been able to posture as pro-refugee and pro-immigrant, knowing how difficult it is for small boats to reach our shores. We watch the British fail to police the English Channel – a body of water that once withstood Nazism but now fails to resist desperate young men in leaky boats – and we feel safe in our demands for an expansively humanitarian entry policy.

But this liberty is a temporary shield. The ecumenical immigration policy championed by the left (in which need, not creed, is the primary consideration) ignores the vital question of how newcomers assimilate into Australian society.

We have reached a situation where our public institutions offer no alternative to a soft multiculturalism that refuses to acknowledge that spiritual and ideological predilections are enduring. We could have acted against Sajid Akram if he held illegal guns; we were powerless to disarm his religious prejudices. His hatred of Israel would have found support in many of our cultural institutions, even if his actions in defence of that hatred have been disowned by them.

The Akrams confirm an unresolved dilemma of multiculturalism: those in antipathy to its values are among its key beneficiaries. The father seems to have done well for himself. The son was born and raised in Australia. As Claire Lehmann argued, his “radicalisation did not occur in a failed state or a war zone. It occurred in southwest Sydney.”

This dilemma was not posed by the deadliest terrorist attack in world history. On September 11, 2001, 19 foreigners flew commercial airliners into the centres of US economic and military power. The introversion of Bondi was spared the US after 9/11. It went to war abroad, in search of monsters to destroy. Australia does not have that option. The monsters are here.

But the US congress did call a 9/11 Commission. It remains the most accomplished public inquiry in US history. The clarity of its final report remains unmatched, a model for how a royal commission into the Bondi massacre might convey its findings.

The moral contortions of identity politics

The multicultural exception for Jews is perhaps the most glaring incongruity of our current moment. Because Jewish Australians are successful, they are often excluded from the protections of the left’s moral schema. They find themselves hated by the anti-Semitic right and demonised by a left that views Israel as a proxy for Western civilisation.

This intellectual anti-Semitism prevents us from indicting dogmas that are explicitly engineered against pluralism.

We end up in the absurdity of Queers for Palestine, a campaign group that speaks to the idiocies of a movement that defends jihadists that would throw its members from buildings. Since October 7, 2023, a minority of progressive Australians have determined to eliminate the only nation in the Middle East where LGBTQI+ rights can be exercised; Israel offers sanctuary to those fleeing Arab homophobia.

Our public discourse is saturated in identity politics. Bondi highlights this without offering an obvious way to dry ourselves off.

The Prime Minister’s reticence over a royal commission is informed by the harm doctrine so fashionable within identity politics: that the public airing of the hatred that allegedly drove the Akrams would (Albanese said) “provide a platform for the worst voices” of anti-Semitism.

As several commentators have observed, this would be like calling off the Nuremberg trials for fear that Nazi race theory might get an airing, that its survivors would have to relive their trauma.

We cannot prosper post-Bondi with such a do-no-harm approach. If being kind – that banal corollary to so much of our public policy – is the solution, we need to be told how greater kindness and largesse towards the perpetrators of the massacre would have turned them into pliable multiculturalists.

Because we have lost our religious sensibilities – a secularisation championed by so many on the progressive left – we are increasingly denuded of a vocabulary needed to understand sectarian violence. Instead, we believe wrapping men like the Akrams in a fuzzy blanket of kindness will vanish away their tribal enmities.

Anti-Semitism is systemic

In the miserable days since Bondi, it is apparent how we have bifurcated into two distinct interpretations of its cause and meaning. This does not map precisely on to a left-right axis; the growing call for a royal commission is increasingly bipartisan.

One side seeks to move on by dismissing the Akrams as an aberration. Nothing to see here.

The other, whose members have been dismayed by the Australian anti-Semitism that has gone unchecked since Hamas raped and killed its way into and out of southern Israel, now fear something far more deep-seated and systemic in the copycat attack on eastern Sydney.

Traditionally, it has been that first camp that has found large causes in singular events. For a half-century, progressives have told us that curing racism and poverty would end crime. Conservatives demurred: better policing, fixing the broken windows, would deter deeper criminality.

As I observed last week, Bondi continues to prompt a diagnostic inversion: a progressive Labor government fixates on a narrow cause – guns and the access of two bad men to them – while its opponents seek answers in the broader culture, with which only a royal commission could begin to grapple.

Anti-Semitism is the oldest hatred. We need a better understanding of how its modern form has been refracted in the prism of soft multiculturalism and identity politics.

A royal commission is not guaranteed to do this. Ironically, using methodologies favoured by progressives – an appreciation for deep cultural causes – would help us grasp any connection between an intellectual phobia towards Israel and the Akrams’ violence against Jewish Australians.

Timothy J. Lynch is professor of American politics at the University of Melbourne

“VISIT OF H.R.H. PRINCESS MARY AND THE EARL OF HARWOOD. MARCH 1934. PRINCESS MARY, THE EARL OF HARWOOD, AND THE GRAND MUFTI, ETC. AT THE MOSQUE EL-AKSA [I.E., AL-AQSA IN JERUSALEM].” LIBRARY OF CONGRESS, LC-M33- 4221.

“VISIT OF H.R.H. PRINCESS MARY AND THE EARL OF HARWOOD. MARCH 1934. PRINCESS MARY, THE EARL OF HARWOOD, AND THE GRAND MUFTI, ETC. AT THE MOSQUE EL-AKSA [I.E., AL-AQSA IN JERUSALEM].” LIBRARY OF CONGRESS, LC-M33- 4221.