… Robeson’s extraordinary career intersects with some of modernity’s worst traumas: slavery, colonialism, the Cold War, Fascism. Stalinism. These are wounds covered over and forgotten, but never fully healed. Not surprisingly, the paths Robeson walked remain full of ghosts, whose whispers we can hear if we stop to listen. They talk to the past, but they also speak to the future.

Jeff Sparrow, No Way But This. In Search of Paul Robeson (2017)

I read Jeff Sparrow’s excellent biography of the celebrated American singer and political activist Paul Robeson several years ago. I was reminded of it very recently with the publication of a book about Robeson’s visit to Australia in November 1960, a twenty-concert tour in nine cities. I have republished a review below, together with an article by Sparrow about his book, and a review of the book by commentator and literary critic Peter Craven. the featured picture is of Robeson singing for the workers constructing the Sydney Opera House.

I have always loved Paul Robeson’s songs and admired his courage and resilience in the face of prejudice and adversity. Duriung his colourful and controversial career (see the articles below), he travelled the world, including Australia and New Zealand and also, Britain. He visited England many times – it was there that my mother met him. She was working in a maternity hospital in Birmingham when he visited and sang for the doctors, nurses, helpers and patients. My mother was pregnant at the time – and, such was his charisma, that is why my name is Paul.

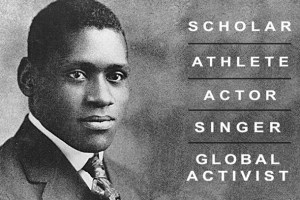

Paul Robeson was a 20th-century icon. He was the most famous African American of his time, and in his time, was called the most famous American in the world. His is a story of political ardour, heritage, and trauma.

The son of a former slave, he found worldwide fame as a singer and an actor, travelling from Hollywood in the USA to the West End of London, to Europe and also Communist Russia. In the sixties, he visited Australia and is long remembered for the occasion he sang the song Old Man River for the workers building the famous Sydney Opera House.

He became famous both for his cultural accomplishments and for his political activism as an educated and articulate black man in a white man’s racist world.

Educated at Rutgers College and Columbia University, he was a star athlete in his youth. His political activities began with his involvement with unemployed workers and anti-imperialist students whom he met in Britain and continued with support for the Republican cause in the Spanish Civil War and his opposition to fascism.

A respected performer, he was also a champion of social justice and equality. But he would go on to lose everything for the sake of his principles.

In the United States he became active in the civil rights movement and other social justice campaigns. His sympathies for the Soviet Union and for communism, and his criticism of the United States government and its foreign policies, caused him to be blacklisted as a communist during the McCarthy era when American politics were dominated by a wave of hatred, suspicion and racism that was very much like we see today,

Paul Robeson, the son of a slave, was a gifted linguist. He studied and spoke six languages, and sang songs from all over the world in their original language.

But his most famous song was from an American musical show from 1927 – Show Boat, by Jerome Kern and Oscar Hammerstein – called Old Man River. The song contrasted the struggles and hardships of African Americans during and after the years of slavery, with the endless, uncaring flow of the Mississippi River. It is sung the point of view of a black stevedore on a showboat, and is the most famous song from the show.

It is a paradox that a song written by Jewish Americans from the Jewish villages of Eastern Europe, the targets of prejudice and pogrom, should voice the cries of America’s down-trodden people.

When the song was first heard, America was a divided country and people of colour were segregated, abused and murdered. The plot of the musical was indeed about race, although it pulled its punches with the romantic message that love is colour-blind

It reflected America’s split personality – the land of the free, but the home of the heartless. Robeson sung the words as they were written, but later in his career, as he became more and more famous, he changed them to suit his own opinions, feelings, sentiments, and politics. So, when he sang to the workers in Sydney, Australia, his song was not one of slavery but one of resistance.

© Paul Hemphill 2025. All rights reserved

For other posts in In That Howling Infinite on American history and politics, see My Country, ’tis of Thee – Matters American

The Big Voice of the Left … Paul Robeson Resounds to this Day

Mahir Ali The Australian November 9, 2010

FIFTY years ago today, more than a decade before it was officially inaugurated, the Sydney Opera House hosted its first performance by an internationally renowned entertainer when Paul Robeson, in the midst of what turned out to be his final concert tour, sang to the construction workers during their lunch break.

Alfred Rankin, who was at the construction site on November 9, 1960, recalls this “giant of a man” enthralling the workers with his a cappella renditions of two of his signature songs, Ol’ Man River and Joe Hill.

“After he finished singing, the men climbed down from the scaffolding, gathered around him and presented him with a hard hat bearing his name,” Paul Robeson Jr writes in his biography of his father, The Undiscovered Robeson. “One of the men took off a work glove and asked Paul to sign it. The idea caught on and the men lined up. Paul stayed until he had signed a glove for each one of them.”

The visit, Rankin tells The Australian, was organised by the Building Workers Industrial Union of Australia and the Australian Peace Council’s Bill Morrow, a former Labor senator from Tasmania.

In a chapter on Robeson’s visit in the book Passionate Histories: Myth, Memory and Indigenous Australia, which will be launched in Sydney tomorrow, Ann Curthoys quotes the performer as saying on the day after his visit to the Opera House site: “I could see, you know, we had some differences here and there. But we hummed some songs together, and they all came up afterwards and just wanted to shake my hand and they had me sign gloves. These were tough guys and it was a very moving experience.”

In 1998, on the centenary of Robeson’s birth, former NSW minister John Aquilina told state parliament his father had been working as a carpenter at the Opera House site on November 9, 1960: “Dad told us that all the workers – carpenters, concreters and labourers – sang along and that the huge, burly men on the working site were reduced to tears by his presence and his inspiration.”

Curthoys, the Manning Clark professor of history at the Australian National University, who plans to write a book about the Robeson visit, also cites a contemporary report in The Daily Telegraph as saying that the American performer “talked to more than 250 workmen in their lunch hour, telling them they were working on a project they would be proud of one day”. [Curthoy’s book, The Last Tour: Paul and Eslanda Robeson’s visit to Australia and New Zealand, was published at last in 2025]

According to biographer Martin Duberman, Robeson wasn’t particularly enthusiastic about the offer of a tour of Australia and New Zealand from music entrepreneur D. D. O’Connor, but the idea of earning $US100,000 for a series of 20 concerts, plus extra fees for television appearances and the like, proved irresistible.

Robeson had once been one of the highest paid entertainers in the world, but from 1950 onwards he effectively had been deprived of the opportunity of earning a living. A combination of pressure from the US government and right-wing extremists meant American concert halls were closed to him, and the US State Department’s refusal to renew his passport meant he was unable to accept invitations for engagements in Europe and elsewhere. Robeson never stopped singing but was able to do so only at African-American churches and other relatively small venues. His annual income dwindled from more than $US100,000 to about $US6000.

At the time, Robeson was arguably one of the world’s best known African Americans. As a scholar at Rutgers University, he had endured all manner of taunts and physical intimidation to excel academically and as a formidable presence on the football field: alone among his Rutgers contemporaries, he was selected twice for the All-American side.

Alongside his athletic prowess, which was also displayed on the baseball field and the basketball court, he was beginning to find his voice as a bass baritone. When a degree in law from Columbia University failed to help him make much headway in the legal profession, he decided to opt for the world of entertainment, and made his mark on the stage and screen as a singer and actor.

An extended sojourn in London offered relief from the racism in his homeland and established his reputation as an entertainer, not least through leading roles in the musical Show Boat and in Othello opposite Peggy Ashcroft’s Desdemona.

(He reprised the role in a record Broadway run for a Shakespearean role in 1943 and again at Stratford-upon-Avon in 1959)

Robeson returned to the US as a star in 1939 and endeared himself to his compatriots with a cantata titled Ballad for Americans.

In the interim, he had been thoroughly politicised, not least through encounters in London with leaders of colonial liberation movements such as Kenya’s Jomo Kenyatta, Ghana’s Kwame Nkrumah and India’s Jawaharlal Nehru.

He had sung for republicans in Spain and visited the Soviet Union at the invitation of filmmaker Sergei Eisenstein.

Robeson’s refusal to reconsider his political affiliations once World War II gave way to the Cold War made him persona non grata in his homeland: his infatuation with the Soviet Union did not perceptibly pale in the face of horrific revelations about Stalinist excesses, partly because he looked on Jim Crow as his pre-eminent foe. It is therefore hardly surprising that exposure in Australia to Aboriginal woes stirred his passion.

On the day after his appearance at the Opera House site, at the initiative of Aboriginal activist and Robeson fan Faith Bandler he watched a documentary about Aborigines in the Warburton Ranges during which his sorrow turned to anger, and he vowed to return to Australia in the near future to fight for their rights. He made similar promises to the Māori in New Zealand.

But the years of persecution had taken their toll physically and psychologically: Robeson’s health broke down in 1961 and, on returning to the US in 1963, he lived the remainder of his life as a virtual recluse. He died in 1976, long after many of his once radical aspirations for African Americans had been co-opted into the civil rights mainstream. His political views remained unchanged.

It’s no wonder that, as writer and broadcaster Phillip Adams recalls, Robeson’s tour was like “a second coming” to “aspiring young lefties” in Australia.

Duberman cites Aboriginal activist Lloyd L. Davies’s poignant recollection of Robeson’s arrival in Perth on the last leg of his tour, when he made a beeline for “a group of local Aborigines shyly hanging back”.

“When he reached them, he literally gathered the nearest half dozen in his great arms.”

Davies heard one of the little girls say, almost in wonder, “Mum, he likes us.”

She would have been less surprised had she been aware of the Robeson statement that serves as his epitaph: “The artist must take sides. He must elect to fight for freedom or slavery. I have made my choice. I had no alternative.”

Left for Good – Peter Craven on Paul Robeson

The Weekend Australian. March 11 2017

What on earth impelled Jeff Sparrow, the Melbourne-based former editor of Overland and left-wing intellectual, to write a book about Paul Robeson, the great African American singer and actor?

Well, he tells us: as a young man he was transporting the libraries of a lot of old communists to a bookshop and was intrigued by how many of the books were by or about Robeson.

All of which provokes apprehension, because politics is a funny place to start with

Robeson, even if it is where you end or nearly end. Robeson was one of the greatest singers of the 20th century. When I was a little boy in the 1950s, my father used to play that velvet bottomlessly deep voice singing not only Ol’ Man River — though that was Robeson’s signature tune and his early recording of it is one of the greatest vocal performances of all time — but all manner of traditional songs. Not just the great negro spirituals (as they were known to a bygone age; Sparrow calls them slave songs) such as Go Down, Moses, but Shenandoah, No, John, No and Passing By, as well as the racketing lazy I Still Suits Me.

My mother, who was known as Sylvie and loathed her full name, which was Sylvia, said the only time she could stand it was when Robeson sang it (“Sylvia’s hair is like the night … such a face as drifts through dreams, such is Sylvia to the sight”). He had the diction of a god and the English language in his mouth sounded like a princely birthright no one could deny.

It was that which made theatre critic Kenneth Tynan say the noise Robeson made when he opened his mouth was too close to perfect for an actor. It did not stop him from doing Eugene O’Neill’s All God’s Chillun’ Got Wings or The Emperor Jones, nor an Othello in London in 1930 with Peggy Ashcroft as his Desdemona and with Sybil Thorndike as Emilia.

Robeson later did Othello in the 1940s in America with Jose Ferrer as Iago and with Uta Hagen (who created Martha in Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?) as his Desdemona. He toured the country; he toured the south, which was almost inconceivable. When he was told someone had said the play had nothing to do with racial prejudice, Robeson said, “Let him play it in Memphis.”

Southern white audiences were docile until Robeson’s Othello kissed Hagen’s Desdemona: then they rioted. Robeson also made a point, at his concerts and stage shows, of insisting the audience not be segregated. James Earl Jones. who would play Robeson on the New York stage, says in his short book about Othello, “I believe Paul Robeson’s Othello is the landmark performance of the 20th century.”

Robeson would play the Moor again in 1959 at Stratford-upon-Avon. By that time, though, he had fallen foul of 1950s America. He had been called before the McCarthyist House Un-American Activities Committee. You can hear a dramatisation of his testimony with Earl Jones as Robeson, which includes an immemorial reverberation of his famous words when senator Francis E. Walter asked him why he didn’t just quit the US and live in Russia.

“Because my father was a slave and my people died to build this country, and I am going to stay here and have a part of it just like you. And no fascist-minded people will drive me from it. Is that clear?”

It’s funny how it was the real communists such as Bertolt Brecht and Robeson who handled the committee best. Still, in an extraordinary act of illiberalism, they took away his US passport and it took two years for the Supreme Court to declare in 1958 in a 5-4 decision that the secretary of state was not empowered to withdraw the passport of any American citizen on the basis of political belief.

It was this that allowed Robeson to do his Othello in Peter Hall’s great centenary Stratford celebration along with Charles Laughton’s Lear and Laurence Olivier’s Coriolanus. It also allowed him to come to Australia. Very early on Sparrow tells the story of watching the clip of Robeson singing Ol’ Man River to construction workers in Sydney with the Opera House still a dream in the process of meeting impediments. The version Robeson sings is his own bolshie rewrite (“I must keep fightin’/ Until I’m dyin’ ”).

Well, fight he did and bolshie he was. I remember when I was a child my father telling me Robeson was a brilliant man, that he had won a sporting scholarship for American football (to Rutgers, in fact), that he’d gone on to receive a law degree (from Columbia, no less) and that he was so smart he had taught himself Russian.

But the sad bit was, according to my father, that he’d become a communist. Understandably so, my father thought, because of how the Americans treated the blacks. My father’s own radical impulses as a schoolboy had been encouraged, as Robeson’s were on a grander scale, by World War II where Uncle Joe Stalin was our ally in the war against Hitler’s fascism.

But this was the Cold War now, and a lot of people thought, with good reason, that it was behind the Iron Curtain that today’s fascists were to be found. Even if others such as the great German novelist Thomas Mann and Robeson thought they were encroaching on Capitol Hill.

Sparrow’s book No Way But This is circumscribed at every point by his primary interest in Robeson as a political figure of the Left rather than as a performer and artist.

It’s an understandable trap to fall into because Robeson was an eloquent, intelligent man of the Left and his status was also for a while there — as Sparrow rightly says — as the most famous black American on Earth. So his radicalism is both pointed and poignant.

His father, who became a Methodist minister, was born a slave and was later cruelly brought down in the world. But, unlike the old Wobblies whose bookcases he transported, Sparrow is not inward with what made Robeson famous in the first place and it shows.

No Way But This is a great title (“no way but this / killing myself, to die upon a kiss” is what Othello says when he’s dying over the body of Desdemona, whom he has killed) but Sparrow’s search for Robeson is not a great book.

As the subtitle suggests, it is a quest book but Sparrow is a bit like the Maeterlinck character cited in Joyce’s Ulysses who ends up meeting himself (whether in his Socrates or his Judas aspect) on his own doorstep. Sparrow goes to somewhere in the US associated with Robeson and meets a black-deaths-in-custody activist full of radical fervour. She introduces him to an old African-American who was in Attica jail for years. There is much reflection on the thousands of black people who were slaves on the plantations and the disproportionate number of them now in US prisons.

Yes, the figures are disquieting. No, they are not aspects of the same phenomenon even though ultimately there will be historical connections of a kind.

And so it goes. But this is a quest book that turns into a kind of travelogue in which Sparrow goes around the world meeting people who might illuminate Robeson for him but don’t do much for the reader except confirm the suspicion that the author’s range of acquaintance ought to be broader or that he should listen to people for a bit more rather than seek confirmation of his own predilections.

There are also mistakes. Sparrow seems to know nothing about the people with whom Robeson did Othello. There’s no mention of Thorndike, and when Ashcroft comes up as someone he had an affair with, Sparrow refers to the greatest actress of the Olivier generation as “a beautiful glamorous star”. Never mind that she was an actress of such stature, Judi Dench said when she played Cleopatra she could only follow Ashcroft’s phrasing by way of homage.

Sparrow also says “American actor Edmund Kean started using paler make-up for the role, a shift that corresponded with the legitimisation of plantation slavery”. Kean, who was the greatest actor of the later romantic period, was English, not American. His Othello would, I think, be more or less contemporary with William Wilberforce lobbying to have slavery made illegal. Sparrow seems to be confusing Kean with Edwin Booth, the mid-century Othello who happens to have been the brother of John Wilkes Booth, the assassin of Abraham Lincoln. But it’s still hard to see where the plantations fit in.

A few pages later — and it’s not important though it’s indicative — we hear of the rumour that Robeson was “romancing Edwina Mountbatten, Countess Mountbatten of Burma”. Well, whatever she was called in the early 1930s, it wasn’t Countess Mountbatten of Burma because her husband, Louis Mountbatten, the supreme allied commander in Southeast Asia during World War II, didn’t get the title until after the Japanese surrendered to him — guess where?

Such slips are worth belabouring only because they make you doubt Sparrow’s reliability generally. It’s worth adding, however, that his chapter about the prison house that the Soviet Union turned itself into is his most impressive. And the story of the last few years of Robeson’s life, afflicted with depression, subject to a lot of shock treatment, with recurrent suicide attempts, is deeply sad.

He felt towards the end that he had failed his people. He just didn’t know what to do. It was the melancholy talking as melancholy will.

It’s better to remember the Robeson who snapped back at someone who asked if he would join the civil rights movement: “I’ve been a part of the civil rights movement all my life.”

It’s to Sparrow’s credit that he’s fallen in love with the ghost of Robeson even if it’s only the spectral outline of that power and that glory he gives us.

Peter Craven is a cultural and literary critic

The Last Tour: Paul and Eslanda Robeson’s visit to Australia and NZ

Recovering the story of a man who was once the most famous African-American in the world and his equally impressive wife, Eslanda, is the task Curthoys, who grew up in an Australian communist family in the 1950s and 60s, sets herself in a new book, The Last Tour: Paul and Eslanda Robeson’s visit to Australia and New Zealand.

It follows the couple’s tour – a mix of his concerts and their public talks and media interviews – to Australia and New Zealand over October, November and December 1960. Curthoys goes further, using the seven-week tour by this celebrated singer to explore the social and political changes just beginning in post-War Australia. Her interest is “the slow transition from the Cold War era of the late 1940s and 50s, to the 60s era of the New Left, new social movements and the demand for Aboriginal rights”.

Curthoys is 79 now, but when Robeson toured she was 15 and living in Newcastle, a city the singer did not visit. Her mother, Barbara Curthoys, a well-known activist and feminist, was a fan of the singer but the trip passed the teenager by.

It was only decades later, as she researched her 2002 book on the 1965 Aboriginal Freedom Ride through regional NSW, that Curthoys connected with the story. As a university student she had taken part in the ride and moved from communism to the New Left. When she approached the subject as a historian, she realised that for some riders, their attendance at Robeson’s concerts five years earlier had been a defining moment in their “understanding of racial discrimination and Aboriginal rights”.

Curthoys has had a long career in research and teaching at the Australian National University and the University of Technology, Sydney. She’s part of a remarkable family, and not just parents Barbara and Geoffrey, who was a lecturer in chemistry at Newcastle University. Her sister Jean is a leading feminist philosopher and her husband, John Docker, has written several books on cultural history, popular culture and the history of ideas.

Curthoys began researching The Last Tour in 2007, but put it aside for another project on Indigenous Australians before resuming work on it during the Covid-19 lockdowns. Post-Robeson, she has worked with two scholars on a forthcoming book on the history of domestic violence in Australia.

The tour, she says, was really several tours rolled into one with the Robesons covering many bases – from music to Cold War politics to feminism to Aboriginal rights. It was a conservative era: Robert Menzies’ Liberals ruled federally and five of the six Australian states had conservative governments. Robeson’s presence went unremarked by governments but for fans of his music – and his ideals – the tour was a significant event that was well covered by the press, even those opposed to his views on the Soviet Union.

For some fans, it was a music tour – 20 concerts in nine cities in Australia and New Zealand, at which Robeson sang his show-stoppers, including Deep River, Go Down, Moses; We Are Climbing Jacob’s Ladder, and the song with which he is always identified, Ol’ Man River. The 62-year-old with the extraordinary voice also delivered “recitations” – a monologue from Shakespeare’s Othello, an anti-segregationist poem Freedom Train, and William Blake’s anthem, Jerusalem.

What a thrill for Australian audiences, some of whom had followed the handsome, 1.9m singer and actor since the 1920s. Even in an age of limited communications, Robeson was well-known here through films; records and radio. Curthoys notes that one indicator of his fame was the way promising Aboriginal singers in the 1930s were dubbed “Australia’s Paul Robeson”.

He was famous – and controversial. Unlike many other supporters of communist ideas, Robeson refused to break from the Soviets after the invasion of Hungary in 1958 and continued to defend Moscow. The “anti-communist repression and hysteria” that gripped the US in the McCarthy era had a profound effect on his life and career, Curthoys writes. He was cited in 1947 by the House Committee on Un-American Activities as “supporting the Communist Party and its front organisations”.

A 1949 US tour was destroyed “after mass cancelling of bookings by venue managers either vehemently opposed to his politics or afraid in such a hostile climate of being classed as communist sympathisers themselves”. Then in 1950, he lost his passport. Over the years, he would “become for communists an emblem of defiance in the face of adversity, and one of the communist world’s most prominent speakers for peace,” Curthoys writes.

Unable to travel until his passport was restored in 1958, Robeson was steadfast in his support for communist ideals. That commitment was evident in Australia when the “peace tour” – built around a series of public meetings – was as important to the singer as the popular concerts where he reached a different audience. Curthoys details a related strand – the “workers’ tour”, which involved seven informal concert performances to groups of railway workers, waterside workers and those at work on the Opera House on that November day.

She says the events revealed much about the “the nature of class in Australia and New Zealand” at a time when “strong and confident trade unions” were interested in “broad cultural concerns”. Over several weeks Robeson attracted people who loved his music alongside those who loved his politics. Far from being shunned for his pro-Soviet views, Curthoys suggests, there was support from two different audiences – music people and “left-wing people who were either pro-Soviet or not”.

Even so, the Cold War anxieties over the Soviets meant a positive reception was not necessarily assured when Paul and Eslanda flew into Sydney at midday on October 12, 1960. They were greeted by several hundred fans carrying peace banners but they faced pointed questions about the Soviet Union at the 20-minute press conference at the airport.

Robeson refused to condemn the suppression of the Hungarian uprising and media reports suggested a torrid exchange. Curthoys reviewed a tape of the press conference and says while the questioning was “a little aggressive”, the event was not as bad as reported in the media. Indeed it was “fairly friendly” albeit for a “bad patch” when Robeson refused to budge on Hungary.

That tape and others, along with newspapers and Trades Hall documentation, yielded rich material but so too did the ASIO files on the couple. At the Palace Hotel in Perth on December 2 an ASIO operative appeared to be among those at a reception organised by the communist-influenced Peace Council. Among guests were the writer (and well-known communist) Katharine Susannah Prichard and “two women by the name of Durack, who were writers and/or artists”.

Curthoys sees Robeson as a “very courageous, very intelligent, intellectual person, very thoughtful about music, about folk music, about people”, but says his commitment to the Soviet Union was a costly mistake. He had embraced Moscow when he and Eslanda visited in 1934 at the invitation of Soviet film director Sergei Eisenstein. Later, Robeson, a fluent Russian speaker, would say it was in the Soviet Union that he felt for the first time he was treated “not through the prism of race but simply as a human being”. Curthoys writes: “The excitement and validation he received during this visit would create a loyalty that later events would not dislodge and the public expression of which would damage him politically, commercially and professionally.”

The couple made several trips to the Soviet Union and accepted its political system completely. Curthoys notes: “They made no public comments about Stalin’s forced collectivisation policies that were in place during the 1930s and led to famine and the loss of millions of lives.” In Sydney Robeson was careful, but on November 5 he celebrated the forthcoming anniversary of the Russian Revolution at the Waterside Workers Federation in Sussex Street. Two days later, during his first public concert in the city, he paid tribute to the Soviet Union as “a new society”.

The Soviet Union had been a great influence but so too was the Spanish Civil War, which Curthoys says helped define his view of the political responsibilities of the artist.

“Increasingly famous as a public speaker, on 24 June, 1937, he made a huge impression at a mass rally at the Albert Hall in London sponsored by prominent figures such as WH Auden, EM Forster, Sean O’Casey, HG Wells and Virginia Woolf, held to raise financial aid for Basque child refugees from the war. In what became his most well-known and influential speech, he stressed how important it was for artists and scientists and others to take a political stand: ‘Every artist, every scientist, every writer must decide NOW where he stands. He has no alternative. There is no standing above the conflict on Olympian heights.’”

After World War II, Robeson was deeply involved in radical and anti-racism politics in the US but in 1947, as the Cold War worsened, he had had enough. He announced he intended to abandon the theatre and concert stage for two years to speak out against race hatred and prejudice. In fact he stopped stage acting for 12 years but continued to perform as a singer, often in support of political causes.

It was another 13 years before Australian audiences heard that glorious voice “live”. Australians, it seemed were primed for Paul. The tour may have been ignored by governments but during her research, Curthoys was “overwhelmed” by people “ready to assist, donating old programs, photographs, pamphlets, records, cassette tapes, invitations and other documents”.

Today, much of the Robeson image is defined by his Opera House performance on November 9 – high culture delivered, without condescension, to a building crew by a champion of the workers. Robeson, in a heavy coat, despite the warm weather, sang “from a rough concrete stage”. A PR expert could not have dreamt up a a better way to “democratise” an opera house than having the “first concert” delivered in its half- built shell. Curthoys shows how the event, no matter how memorialised now, was a small part of a tour that proved a financial and political success for the Robesons, who left Australia on December 4.

A few months later, depressed and exhausted, Robeson tried to commit suicide in Moscow. Over the next three years he was treated but could no longer perform or engage in public speaking. Curthoys notes that though his affairs with other women had strained their marriage, he and Eslanda had a common political vision and were together until her death in 1965. Robeson died on January 23, 1976 at the age of 77.

Helen Trinca’s latest book is Looking for Elizabeth: The Life of

Elizabeth Harrower (Black Inc.)