Preface

The featured image of this post is a profile in crystal of Kemal Atatürk that sits on my bookshelf as a reminder of my late friend and academic colleague Mehmet Naim Turfan. Naim, like millions of his compatriots, harboured a deep affection and respect for the legacy of Atatürk, the founder of modern Türkiye and its first president. It was gifted to me by His wife soon after his passing by his wife Barbara. His doctoral thesis was published posthumously in 2000 as Rise of the Young Turks: Politics, the Miliary and Ottoman Collapse. He is cited several times in the book that is the subject of this article. I thought of Naim often while reading the book and writing what follows.

Enver Pasha, soldier, politician and member of the troika that ruled the Ottoman Empire before and during WW1

Author and journalist Christopher de Bellaigue sets the scene well in a brief but compelling review (published in full below with some excellent pictures, along with a article by the author himself):

”For the historian of the first world war, the Ottoman theatre is a blur of movement compared to the attrition of the western front. Its leading commanders might race off to contest Baku and entirely miss the significance of events in the Balkans, while the diffuse nature of operations tended to encourage initiative, not groupthink. The war of the Ottoman succession, as Sean McMeekin calls it, was furthermore of real consequence, breaking up an empire that had stifled community hatreds, and whose absence the millions who have fled sectarian conflict in our age may rue …

For the Ottomans, the “great war” of western historiography was part of a much longer period of conflict and revolution, and arguably not even its climax. The process started with the collapse of the Ottomans’ Balkan empire – encouraged by Russia, moderated by Britain – and it brought to power the militaristic regime of the Committee of Union and Progress, or CUP. When Turkey entered the European war on 10 November 1914, Ottoman innocence was long gone, the army fully mobilised, the people benumbed by loss and refugees and the empire hanging in the balance. And yet, for the CUP and its triumvirate of leading pashas, the Young Turk troika of Enver, Talat and Djemal, the moment was as fraught with opportunity as it was with danger. On the opportunity side of the ledger was the prospect of riding Germany’s coat tails to victory, overturning the Balkan reverses and winning back provinces in the east from the old enemy, Russia. Enver, the CUP’s diminutive generalissimo, even spoke of appealing to Muslim sentiment and marching all the way to India.

For the Russians, the game was about winning Constantinople (or Tsargrad, as they presumptuously called it) and with it unimpeded access to the Mediterranean through the Bosphorus; it was with “complete serenity”, Tsar Nicholas II informed his subjects, that Russia took on “this ancient oppressor of the Christian faith and of all Slavic nations”

The European war on the eastern and western fronts was characterized by attrition and stalemate, but that waged by the Ottomans and the Russians, and soon, the British and French, was in contrast, highly mobile and constantly shifting, with the exception perhaps of the allied assault on the Gallipoli Peninsula which very soon resembled the trench warfare and brutal but futile offensives that characterized the Western Front. It is difficult to comprehend to scale of the war fought in the Middle East in terms of its territorial extent. From Baghdad to Baku, Gallipoli to Gaza, the Black Sea to the Gulf of Aqaba and the Caspian Sea. It was waged across European and Asian Ottoman lands including present day Greece, Bulgaria and Romania in the west, in the Caucasus in the east, in present day Armenia, Georgia and Azerbaijan and Iran, and in the south in present day Syria, Iraq, Jordan, Israel and Palestine.

Though the Sultan departed, and with him, the Islamic Caliphate, and most of the empire’s non-Turkish lands – were lost, under the leadership of former Ottoman commander and war hero Mustafa Kemal Pasha, the Anatolian heartland resisted and ultimately repelled invading foreign armies, and the Turkish state he created endures today as an influential participant in world affairs.

Casting new light on old narratives

McMeekin, writes de Bellaigue, is an old-fashioned researcher who draws his conclusions on the basis of the documentary record. In the case of a conflict between Ottoman Turkey and Germany on one side, and Russia, Britain and France on the other, and involving Arabs, Armenians and Greeks, this necessitates linguistic talent and historical nous of a high order. McMeekin is at home in the archives of all major parties to the conflict and his accounts of some of the more contested episodes carry a ring of finality. Access to previously closed Russian and Turkish archives has provided new and potentially controversial insights into accepted narratives regarding the last years of the Ottoman Empire. Challenging long accepted narratives, he addresses three of the most enduring shibboleths of the First World War.

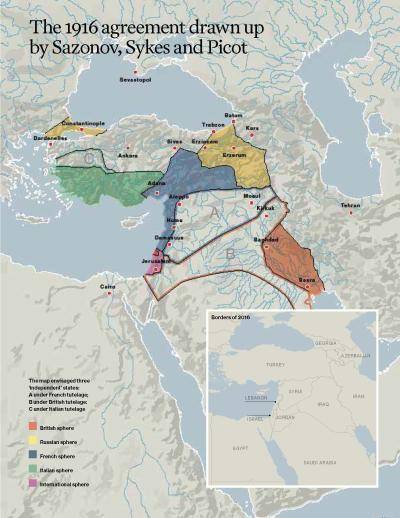

He jumps right in even before he begins his wide-ranging story, leaves hanging in the air like a predator drone until he returns to it in chronologically due course. The Sykes Picot Agreement of 1916 – the bête noir of most progressive narratives of the modern Middle East, and to many ill-informed partisans, the causus bello of the intractable Arab Israeli conflict – was not the brainchild of perfidious Albion and duplicitous France, but rather a plan for the dismemberment of the Ottoman Empire concocted by the foreign minister of Imperial Russia. France’s Monsieur François-George Picot and Britain’s Sir Mark Sykes played second and third violin to the “third man” Sergei Sazonov. Both Russia and France had for decades sought to establish their political, strategic and economic interests at the expense of the so-called “sick man of Europe”, an ostensibly terminal invalid who throughout the nineteenth century, had experienced many deathbed recoveries. Czar Nicholas II, in common with his Russian Orthodox predecessors, dreamt of bringing Istanbul, formerly Constantinople, the heart of the orthodox patriarchate, or Tsargrad into the empire. It was no coincidence that the infamous Sykes Picot pact was outed by Russia’s Bolshevik regime after the collapse of the Czarist regime to discombobulate the revolution’s foremost European enemies.

The second icon of “received history” in McMeekin’s sights, is one Australia’s foundation stories – the ill-starred Dardanelles Campaign of 1915 and particularly, the the ANZAC’s Gallipoli legend. It was, from McMeekin’s perspective, a misconceived, poorly planned endeavour to capture the Ottoman capital, to relieve pressure on Russian forces engaged in bitter fighting in Eastern Anatolia, and potentially, to knock the Ottomans out of the war. Contrary to popular conceptions, the British were not exactly enthused by the idea. First Lord of the Admiralty Winston Churchill’s preference was for an assault on the “soft underbelly” of the empire – the port of Alexandretta in Ottoman Syria (now Turkish Antakya), with its strategic and logistic proximity to the Hijaz railway and the hinterland of the Levant. One indisputable fact about Gallipoli is that it assured the ascent Mustafa Kemal, a key commander who had already distinguished himself in the Balkan Wars, who would go on to conduct a fighting retreat of Ottoman Armies through what is now present-day Palestine and Syria, lead Turkish forces to victory in the war of liberation that followed, and, as Kemal Atatürk, would become the founder of modern Türkiye.

The third widely held narrative concerns the Armenian Genocide. Unlike the rulers of modern Türkiye, McMeekin does not deny its occurrence. Nor does he downplay or even ignore it, as does Israel for the idiosyncratic reason that it potentially minimises the horrors of the Shoah. Rather, he places it in the context of events in the empire’s Anatolian heartland. Two predominantly Armenian provinces in Eastern Anatolia were home to active nationalist independence movements, and these gave tacit and actual support to the Russian forces encroaching on the empire from the Caucasus and the Caspian Sea (in present day Azerbaijan and Georgia). Armenian militias fought alongside Russian forces on the Caucasian front whilst partisans operated behind ottoman lines, and cities, town and villages were actually “liberated”, fostering fears in the Istanbul government of an treasonous” fifth column”. McMeekin acknowledges the death toll of what we now recognise the systematic destruction of the Armenian people and identity which was spearheaded by the ruling Committee of Union and Progress (CUP) and implemented primarily through the mass deportation and murder of around one million Armenians during death marches to the Syrian Desert and the forced Islamization of others, primarily women and children. Whilst most probably died of inhumane treatment, exposure, privation and starvation, unknown numbers were murdered.

Parallels

Reading The Ottoman Endgame, I was reminded often of his compatriot Anthony Beevor’s harrowing tale of the Russian Revolution (reviewed in In That Howling Infinite’s Red and white terror – the Russian revolution and civil war. That Revolution and the end of the Ottoman Empire converged. McMeekin notes that with regard to the war in Anatolia and the Caucasus, the treaty of Brest-Litovsk, which ended the war between Czarist Russia and the Central Powers, was poisoned chalice for both Russia and Turkey and as significant as any of the treaties that followed the end of the war.

I found it fascinating that many individuals who were to play a significant part in the Russian Civil war also feature in Ottoman Endgame. Admiral Alexander Kolchak, commander of the imperial Black Sea fleet and General Anton Deniken, commander of Russian forces on the Caucasian front, became leaders of the Tsarist cause and were to command the counter-revolutionary White forces against the Red Army with the Siberian People’s Army and the Volunteer Army in Ukraine.

None were more prominent or as controversial in western narratives, however, as Winston Churchill. As noted above, McMeekin lays to rest the notion that the Dardanelles campaign and Gallipoli were Churchill’s sole doing and his folly – though he did blame himself later on and has been pilloried for it ever since. Ironically, once disgraced, and having volunteered to serve on the Western Front, at the end of the war, he was brought back into Lloyd George’s cabinet as Secretary of State for War. There, he advised against military intervention against Kemal’s nationalist forces and indeed mused about the option of dumping the Sazonov-Sykes-Picot dispensation imposed on the moribund empire’s Arab provinces after the armistice and of restoring the prewar territorial status quo, a kind of circumscribed Ottoman Redux. And yet, as civil war broke out and spread in the nascent Soviet Union, he was alone of his cabinet colleagues in advocating for a full-on allied intervention. Critics claimed that he dreamt, – though some believed that he fantasized – about of creating an effective White army and a borderlands alliance to defeat the Bolsheviks. But his aspirations were foiled by the imperialism of the White leadership and of White officers, and the various national movements’ fear that that if the Whites prevailed, they would restore Russian rule. Britain’s rulers were reticent about shoring up and providing financial, material support and also, soldiers sailors and airmen to brutal to demonstrably homicidal Cossack brigades and revanchist and reactionary royalist autocrats. It is not without reason that admirers and critics alike would agree that Winston had more positions than the Karma Sutra.

The Russian Revolutions – there were two, in February and October 1917 – and the Civil War that followed it, the disintegration of the Ottoman Empire followed by foreign intervention, the war of liberation, and the creation and endurance of Türkiye can be said to have defined the contours of modern Middle Eastern geopolitics, setting the stage for many if not most of the conflicts that have inflicted the region since, including three Gulf wars, the rise and fall of the Islamic State, the Lebanese, Iraqi and Syrian civil wars, and the Arab-Israel conflict, arguably the most intractable conflict of modern times. Cold War and also, the current Ukraine war.

In the wake of the fall of the Russian Empire, the Twentieth Century was not kind to the countries of Central and Eastern Europe. Historian Timothy Snyder called them “the blood lands”. Nor was it kind to the heirs and successors of the Ottoman Empire. Though the tyranny and oppression and the death and destruction wrought by rulers and outsiders upon the lands and peoples of the Middle East has been significantly less than that endured by the people of Eastern Europe and Russia, the region would fit Snyder’s sombre soubriquet.

© Paul Hemphill 2025. All rights reserved

Also in In That Howling Infinite, see Ottoman Redux – an alternative history and Red and white terror – the Russian revolution and civil war

For more on the Middle East, see A Middle East Miscellany

To judge from press coverage, the emergence of Islamic State has brought about a cartographic revolution in the Middle East. With the borders of Syria and Iraq in flux, journalists have resurrected the legend of Sykes-Picot, wherein Britain and France are said to have divided up the Ottoman empire between them in an agreement signed 100 years ago, in May 1916. Russia’s intervention in Syria, by upstaging the United States and her allies, seems in this view to be completing the rout of western influence in the Middle East, putting the final nail in the coffin of ‘Sykes-Picot’.

Rarely has history been more thoroughly abused. In reality, none of the contentious post-Ottoman borders of the Middle East was settled by Sykes and Picot in 1916: not the Iraq-Kuwait frontier notoriously crossed by Saddam’s armies in 1990, not those separating the Palestinian mandate from (Trans) Jordan and Syria, not the highly contested and still-in-flux Israeli/Palestinian partition of 1948, nor, in the most relevant example from today, those separating Syria from Iraq.

To take an obvious example from recent headlines, Mosul, the Iraqi city whose capture in June 2014 led Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi of Islamic State to proclaim himself Caliph Ibrahim, was actually assigned to French Syria in the 1916 agreement.

Journalists are even more spectacularly wrong in describing the Ottoman partition agreement as exclusively (or even primarily) a British-French affair, omitting the driving role played by Tsarist Russia and her Foreign Minister, Sergei Sazonov.

The final terms of what should more accurately be called the Sazonov-Sykes-Picot agreement were actually hashed out in the Russian capital of Petrograd in the spring of 1916, against the backdrop of crushing Russian victories over the Turks at Erzurum, Erzincan, Batum, and Trabzon (the British were reeling, having been humiliated at Gallipoli and in Iraq, where an expeditionary force would shortly surrender).

The conquest of northeastern Turkey in 1916 left Russia, unlike her grasping allies, in possession of most of the Ottoman territory she was claiming – barring only Constantinople (called ‘Tsargrad’ by the Russians), which still needed to be taken.

At the dawn of 1917, Tsarist Russia was poised to inherit the crown jewels of the Ottoman empire, including Constantinople, the Straits, Armenia, and Kurdistan, all promised to her in the Sazonov-Sykes-Picot Agreement. Along the Black Sea coast, Russian engineers were building a rail line from Batum to Trabzon, with the latter city a supply base for the Caucasian Army, poised for a spring assault on Sivas and Ankara. With Russia enjoying virtually uncontested naval control of the Black Sea, preparations were underway for an amphibious strike at the Bosphorus, spearheaded by a specially created ‘Tsargradskii Regiment’.

After watching her allies try, and fail, to seize the Ottoman capital during the Dardanelles/Gallipoli campaign of 1915 (when Sazonov had first put forward Russia’s sovereign claim on Constantinople and the Straits), Russia was now poised to seize the prize for herself – weather permitting, in June or July 1917.

Of course, it did not turn out that way. After the February Revolution of 1917, mutinies spread through the Russian army and navy, including the Black Sea fleet, just as it was poised to strike.

In a remarkable and little-known coincidence, on the very day the Foreign Minister of the Provisional Government, Pavel Milyukov, first aroused the anger of the Petrograd Soviet and the Bolsheviks by refusing to renounce Russia’s territorial claims on the Ottoman empire – April 4, 1917 – a Russian naval squadron approached the Bosphorus in ‘grand style’, including destroyers, battle cruisers, and three converted ocean liner-carriers which launched seaplanes to inspect Constantinople’s defences from the air. The amphibious plans were not abandoned until fleet commander Admiral AV Kolchak threw his sword overboard on June 21 during a mutiny. Even after ‘revolutionary sailors’ had taken control of the Black Sea fleet, a Russian amphibious strike force landed on the Turkish coastline as late as August 23, 1917, in one last sting by the old Tsargrad beast.

After the Bolsheviks took power, Russia collapsed into civil war, which left her prostrate, at Germany’s mercy. By signing a ‘separate peace’ with the Central Powers at Brest-Litovsk in March 1918, Russia forfeited her treaty claims to Armenia, Kurdistan, Constantinople, and the Straits, throwing the Sazonov-Sykes-Picot agreement of 1916 into chaos, even as new claimants were appearing on the scene, such as Italy and Greece – not to mention local actors: Jewish, Arab, and Armenian troops were attached as national ‘Legions’ to General Allenby’s mostly British army as it rolled up Palestine and Syria. These forces, along with French, Italian, and Greek expeditionary forces sent after the war, and the Turkish nationalists who regrouped under Mustafa Kemal in Ankara to oppose them, would determine the final post-Ottoman borders in a series of small wars between 1918 and 1922, with scarcely a nod to the Sazonov-Sykes-Picot Agreement.

While Russia’s forfeiture of her claims in 1918 was welcome, in a selfish sense, to the other players vying for Ottoman territory, it was not necessarily a positive one for the region. In the absence of Russian occupying troops to police the settlement, the

Allies, in 1919, offered Russia’s territorial share, now defined (in deference to Woodrow Wilson) as mandates, to the United States – only for the Senate to vote down the Versailles Treaty, rendering the arrangement moot. Lacking Russian or American troops as ‘muscle’, the Allies leaned on weaker proxies such as the Italians and, more explosively, local Greeks and Armenians, which aroused the anger of the Muslim masses and spurred the Turkish resistance led by Kemal (the future Atatürk). Armenians, Greeks and Kurds, too, could only lament the vacuum left behind by the departing Russians, which left them to face Turkish wrath alone.

Soviet Russia re-emerged as a player in the Middle East fairly quickly, not least as Mustafa Kemal’s key diplomatic partner during his wars against the West and its proxies from 1920-22. In a reminder of the enduring prerogatives of Russian foreign policy, the Cold War kicked into high gear when Stalin made a play for Kars, Ardahan, and the Ottoman Straits in 1946: these moves, along with the British withdrawal from Greece, Turkey, and Palestine, inspired the Truman doctrine.

In an eerily similar replay of the history of 1917-18, the collapse of Soviet power in 1991 led Moscow to turn inward, withdrawing from the Middle East and inaugurating a period of US and western hegemony in the region, which turned out no less well than the Middle Eastern free-for-all of 1918-22. A prostrate and impoverished Russia put up no objection during the First Gulf War of 1991, and did little more than sputter during the Iraq War of 2003. Russia’s recovery of strength and morale in the Putin years led, almost inevitably, to her return in force to the Middle East – from which, in reality, she never truly left.

The Russian return to the region, along with Turkey’s increasingly overt hostility over her Syrian intervention, resurrects historical patterns far, far older than Sykes-Picot. For centuries, the Ottoman empire was the primary arena of imperial ambition for the Tsars, even as Russians were the most feared enemies of the Turks. In many ways, the Crimean War of 1853-56, which saw western powers (Britain, France, and an opportunistic Piedmont-Sardinia) unleash an Ottoman holy war against the Tsar to frustrate Russian ambitions in the Middle East, is a far more relevant analogy to the present crisis in Syria than the pseudo-historical myths of 1916. It is time we put the Sykes-Picot legend in the dustbin where it belongs.

Diplomatic carve-up: the third man

In David Lean’s 1962 film, ‘Lawrence of Arabia’, a cynical British official explains how the carcass of the Ottoman Empire was to be divided at the end of the First World War under the Sykes-Picot Agreement.

‘Mr Sykes is an English civil servant. Monsieur Picot is a French civil servant. Mr Sykes and Monsieur Picot met and they agreed that after the war, France and England would share the Turkish Empire, including Arabia. They signed an agreement, not a treaty, sir. An agreement to that effect.’

This summary of wartime diplomacy has proved long-lived. It encapsulates the less than honest dealings of the British government with the Arabs – who wanted independence after being liberated from Turkish domination, rather than rule by the European colonial powers – but it leaves out the key figure in the deliberations, Sergei Sazonov, Russian foreign minister, 1910-1916.

Sazonov was one of the most significant diplomats both before and during the Great War. It was thanks to his adroit manipulation that Britain and its allies came to accept that Russia would gain the Ottoman capital Constantinople, in the event of an Allied victory, an outcome that Britain had tried for decades to prevent.

At the talks in the Russian capital Petrograd in 1916, the British and French emissaries were far lesser agents of empire than their host.

Sir Mark Sykes was a gifted linguist, travel writer and Conservative politician, but no top-flight diplomat. As for François Georges-Picot, he was an experienced diplomat and lawyer and noted advocate for a greater Syria under French rule.

But with France having no troops in the eastern theatre of war, he had to accept Russia’s demand to swallow up large parts of what is now eastern Turkey, but which Paris had set out to claim.

Sykes died of influenza in 1919 at the Paris Peace Conference, where Sazanov represented the White Russians. He died in Nice in 1927

The Ottoman Endgame: War, Revolution, and the Making of the Modern Middle East, 1908-1923” by Sean McMeekin

Czar Nicolas I of Russia is sometimes credited with coining the phrase “Sick Man of Europe” to describe the decrepit Ottoman Empire of the mid-nineteenth century. By the early 20th century, there could be little doubt that the disparaging sobriquet applied in spades. The Ottoman Empire was soundly defeated in two Balkan wars in 1912 and 1913 by the comparatively pipsqueak countries of Bulgaria, Greece, Montenegro and Serbia. One result of the wars was that the Empire lost all of its European territories to the west of the River Maritsa, which now forms the western boundary of modern Turkey. Then, when World War I broke out, the Ottomans made the disastrous decision to side with the Central Powers against the Triple Entente, ending up on the losing side of that cataclysm.

A popular theory is that the carving up of the Ottoman lands after the war, pursuant to the Sykes-Picot Agreement between France and Britain, is the source of many of the problems of the current Middle East. In The Ottoman Endgame, Sean McMeekin concedes that it is not wrong to look to the aftermath of the war for the roots of many of today’s Middle Eastern problems, but the “real historical record is richer and far more dramatic than the myth.” For example, the notorious Sykes-Picot Agreement was sponsored primarily by Russia, whose foreign secretary, Alexander Samsonov, was the principal architect of the agreement. McMeekin’s retelling of the demise of the Ottoman Empire and its recrudescence as modern Turkey is a fascinating and complicated narrative.

Among the interesting facts McMeekin points out is that according to an 1893 census only 72% of the Ottoman citizens were Muslim, and that in the middle of the 19th century the majority of the population of Constantinople may have been Christian. The Balkan Wars started a trend, exacerbated by World War I, toward ethnic cleansing, with hundreds of thousands of Christians leaving the Empire and similar numbers of Muslims moving from territory lost by the Empire to areas it still controlled.

We in the West tend to think of World War I as a static slugfest conducted in the trenches of northern France. But the war in the East, particularly as it applied to the Ottoman Empire, was a much more mobile affair. In fact, the Ottomans ended up fighting the war on six different fronts, as the Entente Powers invaded them from many different angles.

Winston Churchill in 1914

At the outbreak of WWI, the Ottomans allied themselves with Germany out of fear of Russia, which had coveted control over the straits connecting the Black and Mediterranean seas for centuries. In 1914 the Russians invaded Eastern Anatolia and met with initial success. However, Russia feared its early success was quite precarious, and so it inveigled its ally, Britain, to launch a diversionary assault on the Gallipoli peninsula. The “diversion” became one of the most deadly killing grounds of the war, as the British poured hundreds of thousands of men into the battle in hopes of breaking the stalemate on the Western Front. The author credits Russian prodding more than Winston Churchill’s stubbornness for the extent of the British commitment. The Ottomans, led by Mustapha Kemal (later to be known as Ataturk, the “father of modern Turkey”), prevailed in this hecatomb, showing that there was still plenty of fight left in the “Sick Man.”

Turkish General Mustafa Kemal, Gallipoli, 1915

The Ottomans also soundly defeated the British in Mesopotamia (modern Iraq) in late 1915, but they were less successful against the Russians, who invaded across the Caucasus and held much of eastern Anatolia until the Bolshevik revolution in 1917 caused them to withdraw voluntarily. The British ultimately prevailed against the Ottomans in 1918 by invading from Egypt through Palestine, with a little help from the Arabs of Arabia.

The Treaty of Versailles, which ended the war in Europe in 1919, did not end the war for the Ottomans. The victorious Allies were ready to carve up much of the Empire for themselves. The Ottoman armies were to disband; England was to keep Egypt and to get Palestine and Mesopotamia; France was to get Syria, Lebanon, and parts of modern Turkey; and Greece was to get a large swath of western Turkey. All might have gone according to that plan, but Mustapha Kemal (Attaturk) was still in charge of a small but effective fighting force in central Anatolia. Attaturk husbanded his forces and fought only when he had an advantage. In a war that lasted until 1923, he was able to expel the Greeks from Anatolia and to establish the boundaries of modern Turkey.

McMeekin deftly handles this complexity with a lucid pen. His descriptions of the various military campaigns are riveting. This is not to say that he shortchanges the political machinations taking place. He gives more than adequate coverage to the “Young Turks,” a triumvirate that ruled the Empire from 1909 until they eventually brought it to its ruin in 1919. He also covers the Armenian massacres as objectively as possible, given the enormity of the events described.

Evaluation: This is a very satisfying book and an excellent addition to the enormous corpus of World War I literature. The book includes good maps and photos.

Published by Penguin Press, an imprint of Penguin Random House, 2015