“We remember emotions … long after the details have faded. For the potency of emotion is barnacled on memory … and I know I’ll remember forever how I will feel when the vote for an Indigenous voice to parliament is declared. Win or lose”. Nikki Gemmell, The Weekend Australian, 23rd September 2023

“At a time when surveys tell us our sense of national pride is falling to alarming levels, we need to ask whether rejecting a voice would help us feel proud of our nation or fuel the growing sense of disconnection”. Chris Kenny, The Weekend Australian, 23rd September 2023

In July, I wrote in A Voice crying in the wilderness:

“Peter Dutton declared that “the Prime Minister is saying to Australians ‘just vote for this on the vibe”. And yet, it is the “vibe” that will get The Voice over the line. Perhaps the good heart will prevail Australia-wide on polling day and those “better angels of our nature” will engender trust in our indigenous and also political leaders to deliver an outcome that dispels the prevailing doubt, distrust and divisiveness, and exorcise the dark heart that endures still in our history, our culture and our society. Because if the referendum goes down, none of us will feel too good the morning after …

The divisiveness of this referendum will probably be felt for years to come. The polarization it has brought into the open (for some would argue that it has already been there as illustrated by our perennialcukrure and history wars) is a path from which it is notoriously hard to turn back. Whether you were “Yes” or “No” may well will be a key marker of political identity? Will it also some to symbolize Australia’s great continental divide?

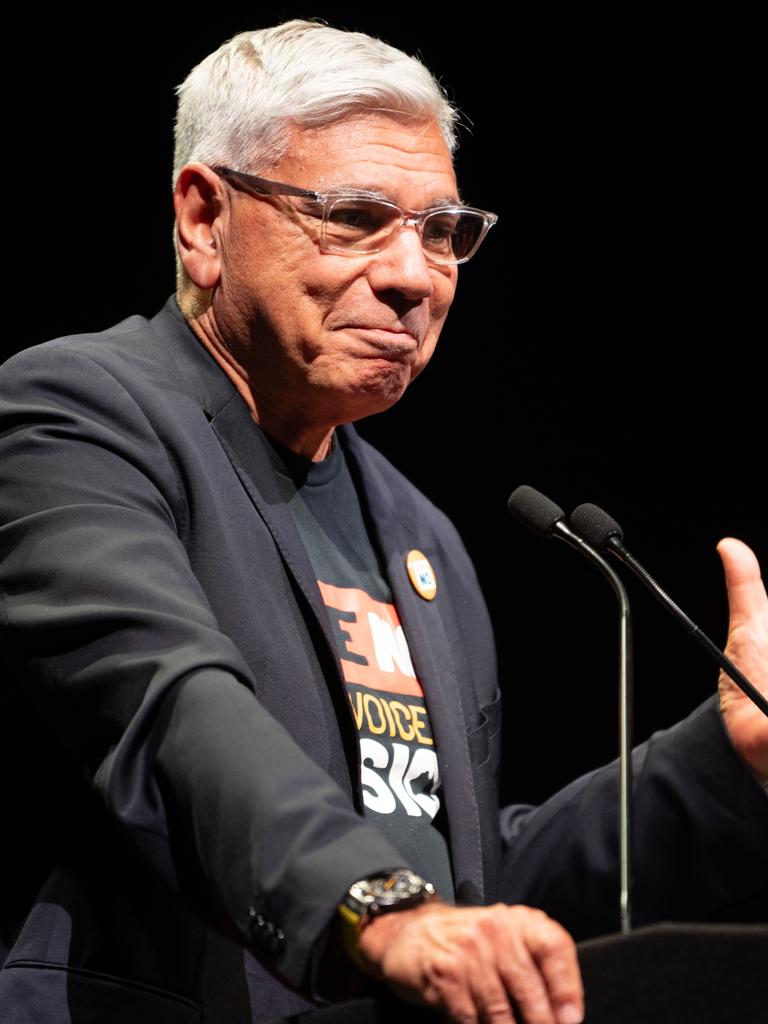

Sky after Dark and News Corp opinionista Chris Kenny, who is almost alone among his colleagues in speaking out in support of the Indigenous and Torres Strait Islander Voice to Parliament, wrote today of the daunting prospect of a No vote on October 14th, and what it might mean for our country and how we feel about it, and also, about ourselves as Australians. To help readers scale The Australian’s pay-wall, I republish it below.

Here are some cogent points from his article:

First and foremost, a No victory would have repudiated Indigenous aspiration, rejecting a proposal for constitutional recognition and non-binding representation formulated after decades of consideration and consultation. This would not so much be a setback for reconciliation but a roadblock that will take many years to get around …

Would a No vote resolve a single issue or merely delay our attempts to resolve them? Would it make us a better nation, or anchor us to unflattering elements of our past?

Would a Yes victory give us a sense of accomplishment and set us on a course for improvement? Would a Yes vote rejuvenate reconciliation and wrap our arms around Indigenous Australians and their challenges?

Would a Yes victory display a bigger, more optimistic and accepting country? Would a No vote confirm us as a frightened, insular and small-minded nation?

While the No leadership would presumably counsel against celebrations in favour of making sober pronouncements about preventing a constitutional mistake, there would likely be outbreaks of triumphalism from many No supporters if they defeat the referendum proposal.

This would create a harrowing contrast with a mournful Yes camp and the reality of Indigenous Australians feeling rejected in their own country.

Where Yes would have provided a path forward, with immediate work to be done to legislate, construct and implement the voice, defeat will lead to nothing. The task ahead will be simply a return to the status quo, the failed status quo.

Indigenous people, communities and organisations understandably would feel dispirited. Whatever the merits of the respective campaigns, negative politics again would have proven more effective than positive advocacy – a misleading scare campaign would have thwarted a carefully devised and constitutionally conservative reform.

A nation that has been talking the talk on reconciliation would have been revealed as too timid to walk the walk.

We would have spent decades of consideration and consultation to come up with the desired constitutional amendment, and then strangely rejected it.

A country in which all sides of politics say they want reconciliation, representation and recognition would have deliberately refused to give Indigenous people a guaranteed say on matters affecting them. We would have become, for a time at least, the scared weird little country”.

Read the full article below, but first, Back to Gemmell:

“Once upon a time I was tremendously naive. I assumed the Voice would bring Australia together, in joy and healing; that it would mark a new waypoint of maturity in the evolution of our nation. In simpler times I dreamed that the vision of an advisory body on Indigenous affairs, painstakingly devised over 15 long years, would be agreed to, and a new era of nationhood would be ushered in.

The proposal felt necessary, suturing, for all of us. It felt like a proposal that went some way towards lifting the corrosive weight of past wrongs. Considered and careful, it seemed a simple request: for an Indigenous committee to be able to advise parliament on Indigenous issues, without being able to make laws or control funding. Yet what a sour-spirited campaign we’ve seen from the forces determined to scupper this vision …

More than 80 per cent of Indigenous people support this voice proposal. The idea came directly from Aboriginal communities, not politicians. I cannot imagine the broken hearts among many of them if this proposal isn’t carried; it would feel like a soul blow, along with all the other soul blows over generations, that would reverberate for years to come.

Once I dreamt of a feeling of great national pride, and relief, following a successful vote for the Voice. Now I worry there’ll be despair and disbelief among many, that in the end it came to this. And anger. Towards one of its scupperers-in-chief most of all. I feel certain Mr Dutton will never become prime minister if the No vote prevails. Be careful what you wish for, sir. The feeling towards you will linger, long after the specifics have faded”.

Press Gallery journalist of the year David Crow observed in the Sydney Morning Herald on 19th June, “The Voice is more than recognition because Indigenous leaders wanted practical change. The terrible suffering of First Australians over 235 years gave those leaders good cause to demand a right to consult on federal decisions, even at the risk of a tragic setback for reconciliation if the referendum fails. Practical change is ultimately about power, and the polls suggest many Australians do not want to give Indigenous people more power. It is too soon to be sure”.

A gloomy prospect, eh?

See other related stories in In That Howling Infinite:

- The Uluru Statement from the Heart

- A Voice crying in the wilderness

- We oughtn’t to fear an Indigenous Voice – but we do

- Warrior woman – the trials and triumphs of Marcia Langton

- If you can bear to hear the truth you’ve spoken … the emptiness of “No”

- Martin Sparrow’s Blues

- The Frontier Wars – Australia’s heart of darkness

- Dark Deeds in a Sunny Land – a poet’s memorial to a forgotten crime

No vote would confirm us as a frightened, insular nation

A morning is looming for this nation, just three weeks away, that warrants attention from all voters entrusted with a historic choice.

My worry is that, instead of Ronald Reagan’s Morning in America, the dawn after the voice referendum will herald Kris Kristofferson’s Sunday Morning Coming Down. We owe it to ourselves to think carefully about what a No vote would say and do in this country. When we wake on Sunday, October 15, it will be too late to reconsider.

First and foremost, a No victory would have repudiated Indigenous aspiration, rejecting a proposal for constitutional recognition and non-binding representation formulated after decades of consideration and consultation. This would not so much be a setback for reconciliation but a roadblock that will take many years to get around.

Similar to how the same-sex marriage plebiscite overwhelmed the gay and lesbian communities with a sense of acceptance and inclusion, a No victory would represent a fend-off to our Indigenous population. They were promised recognition, engaged in good faith to find a suitable path, made their considered request to the nation, and their fellow citizens will have slammed a door in their face.

And why? To save the nation from the risk of entrenched racial division? Or to deliver an ephemeral partisan win?

After a No victory (the phrase seems like an oxymoron) we would face a vacuum, with Labor, Greens and Liberal voice supporters left defeated and impotent, and the Coalition leadership promising more of the same – although weirdly, a vague promise of some kind of legislated voice in the future. If the referendum is defeated, we would be a discombobulated, dispirited and divided federation for some time to come.

Offers of a second referendum would be seen as a cruel joke. The option of bipartisan support for purely symbolic recognition in the preamble would be the epitome of condescension – telling Indigenous Australians we have rejected their voice but propose, instead, something less, something we are prepared to give, not because it is worthy but because it is easy.

Beads and trinkets.

This strikes to the heart of the reconciliation bargain. Reconciliation is about making good and restoring friendly relations – it is about compromise. Just as apologies require acceptance, reconciliation demands concession from all sides.

Indigenous people have provided a road map to put the sins and trauma of the past behind us and forge a future together. The No campaign rejects this because they believe they will lose something, or risk losing something. This seems selfish and paranoid given we are talking about only a constitutional guarantee to have some kind of body giving Indigenous people a non-binding say on issues that affect them.

What the No campaign is saying is that they want reconciliation without compromise or cost. They want reconciliation where the aggrieved party is given nothing, not even a constitutional protection that injustices cannot easily be perpetrated against them again.

This represents a shrivelled view of this nation’s history and future. The No campaign wants our political architecture to curl up like an echidna under attack, remaining defensive and prickly until the Indigenous issues go away.

If we put aside the deceptive scare campaigns from the No side, which pretends the voice will have real power rather than merely an advisory platform, there is an even uglier aspect to the voice opposition. The campaign has increasingly morphed into an opportunity to vent grievances against any aspect of Indigenous people’s place in our society.

The No advocates now argue that if you do not like welcomes to country, you should vote No to a voice. If you think a lot of money is wasted on Indigenous programs, vote No. If you think Indigenous people should not be given additional opportunities for university, jobs or contracts, vote No. If you think we hear too much about Indigenous culture and history, vote No. If you oppose treaties, Vote No. And if you do not want to shift the date of Australia Day, vote No.

This has become a grab-bag of anti-Indigenous grievance, which makes it the worst manifestation of politics this nation has seen in living memory.

But it is also a collection of issues that will continue to be debated and tackled, whether we have an Indigenous voice or not – which makes the argument inane.

There is a harsh, resentful and divisive element in the debate. And we must be able to call it out without the shrill cries that we are accusing others of racism or demonising people for their views.

It is clear many voters do not want to be troubled by Indigenous issues or aspirations. They might have little or no contact with Indigenous people or problems and want it all to go away. That is a benign and plausible interpretation of what seems to be a visceral rejection of the voice proposition.

These sentiments are not reason enough to vote No. And it should be beneath the No campaign to attempt to exploit them.

Voting No will not make anything go away, except a voice.

Prominent No campaigner Nyunggai Warren Mundine, for instance, wants to shift the date of Australia Day and supports treaties and other agreements between Indigenous groups and governments. And state governments are negotiating treaties and establishing voices regardless.

Yet the No campaign creates irrational fear about treaties and Australia Day. If the No case wins, Mundine and others still will advocate for treaties and shifting Australia Day. So, what is the scare campaign about?

The lead No campaigner, opposition Indigenous Australians spokeswoman Jacinta Nampijinpa Price, is a brave advocate. I have helped to platform her determined efforts to give voice to grassroots Indigenous people for many years, helping her to become a national voice.

Price began speaking up for Indigenous Australians, for her community, as an Alice Springs councillor and entered federal politics to become a voice for the “silent victims” in Indigenous communities. So it is paradoxical that her robust politicking is probably the most influential factor in threatening a permanent Indigenous voice.

Her good intentions are beyond question; Price, her family and supporters believe a voice will amplify the views of the wrong people – the same Indigenous leadership she and her family have battled for years.

This novice senator and rising political star is campaigning against the possibility of a bad voice – yet the Coalition promises to legislate a voice, go figure.

The alternative was for the Coalition to throw in their lot with the voice and ensure it is effective and driven by grassroots concerns – practical rather than ideological. We will never know what might have been.

Taken to its logical conclusion, this fear of the voice running astray is a surrender that would have thwarted the creation of our Federation in the 1890s. Any representative or governance model requires constant engagement and vigilance to protect the complacent mainstream from the activism of the ideologues.

The Coalition decided instead to make this a partisan contest. While Anthony Albanese must wear his share of blame for the failure of bipartisanship, it is rich indeed for the Coalition to blame Labor for the division when it deliberately chose to make this a defining debate between the major parties.

If it is successful, the No campaigners would have done nothing but preserve a situation that the entire nation knows is grossly unsatisfactory. How would history judge them?

We should consider what this does to our sense of worth as a nation. At a time when surveys tell us our sense of national pride is falling to alarming levels, we need to ask whether rejecting a voice would help us feel proud of our nation or fuel the growing sense of disconnection.

Would a No vote resolve a single issue or merely delay our attempts to resolve them? Would it make us a better nation, or anchor us to unflattering elements of our past?

Would a Yes victory give us a sense of accomplishment and set us on a course for improvement? Would a Yes vote rejuvenate reconciliation and wrap our arms around Indigenous Australians and their challenges?

Would a Yes victory display a bigger, more optimistic and accepting country? Would a No vote confirm us as a frightened, insular and small-minded nation?

While the No leadership would presumably counsel against celebrations in favour of making sober pronouncements about preventing a constitutional mistake, there would likely be outbreaks of triumphalism from many No supporters if they defeat the referendum proposal.

This would create a harrowing contrast with a mournful Yes camp and the reality of Indigenous Australians feeling rejected in their own country.

Where Yes would have provided a path forward, with immediate work to be done to legislate, construct and implement the voice, defeat will lead to nothing. The task ahead will be simply a return to the status quo, the failed status quo.

Indigenous people, communities and organisations understandably would feel dispirited. Whatever the merits of the respective campaigns, negative politics again would have proven more effective than positive advocacy – a misleading scare campaign would have thwarted a carefully devised and constitutionally conservative reform.

A nation that has been talking the talk on reconciliation would have been revealed as too timid to walk the walk.

We would have spent decades of consideration and consultation to come up with the desired constitutional amendment, and then strangely rejected it.

A country in which all sides of politics say they want reconciliation, representation and recognition would have deliberately refused to give Indigenous people a guaranteed say on matters affecting them. We would have become, for a time at least, the scared weird little country.