How do you see my country? Dusky maidens in desert tents offering dates on golden plates?

Algerian secret agent Mohammed Ibn Khaldun to Tom Quinn, Spooks, 2,Ep 2

How often have we heard the exclamation “it’s like something out of the Arabian Nights”? We’ve said it ourselves as we walked down the Suq al Hamadiyya in Old Damascus and al Wad and Daoud Street in Old Jerusalem, in an ersatz Bedouin tent-restaurant just down the road from Palmyra and a similar night out near Petra. It’s as if the local tourist industry folk expect us westerners to enjoy, nay, expect this kind of entertainment.

But whereas since the translation of The Arabian Nights, we have loved the tales, we have also taken from them a distorted impression of the Middle East, a pastiche of palm trees, minarets and camels like the illustrations of the old boxes of figs and of Fry’s Turkish Delight.

So, how did we get here?

From a historical European perspective, the East or Orient has long been perceived as an unknown, alien, and, therefore, alluring world, that has existed for centuries, even millennia. It’s spell persists to this day, enchanting, seducing, and seducing soldiers, adventurers, travelers, troublemakers, writers, artists, and musicians.

This enduring fascination with the East gave rise to the descriptor Orientalism. In art history, literature, and cultural studies it described the imitation or depiction of aspects of the Eastern world largely by writers, designers, and artists from the Western world. Since the publication Palestinian America academic Edward Said’s seminal work Orientalism (1978) much of academic discourse has begun to use the term to refer to the generally nurturing though patronizing Western attitude toward societies in the Middle East, Asia, and North Africa.

But more on Orientalism and Edward Said later. First, we’ll take look at one of the most popular manifestations of western culture’s relationship with the East.

One Thousand and One Nights (أَلْفُ لَيْلَةٍ وَلَيْلَةٌ, Alf Laylah wa-Laylah) is a collection of folk tales compiled in Arabic during medieval times in what is recognized as the Islamic Golden Age, a period of scientific, economic and cultural flourishing in the history of Islam, traditionally dated from the 8th century to the 13th century. It known in English as The Arabian Nights – from the first English-language edition in the early eighteenth century entitled The Arabian Nights’ Entertainment. Many European translations followed, but none more racy and picaresque that of English explorer, polymath and enfant terrible Richard Burton in 1885; it was an abridged version of this, purchased from a budget book store in King Street, Sydney, that I read the first time i got to meet Mademoiselle Scheherazade. The featured image is from that book’s dust cover.

The stories were gathered over many centuries by various authors, translators, and scholars across the Middle East and South Asia, and North Africa. They originated in ancient and medieval Arabic, Egyptian, Indian, Persian, and even Mesopotamian folklore and literature. Many were originally folk stories from the Abbasid and Mamluk eras, while others, especially the central story of Scheherazade are most likely drawn from the Pahlavi Persian work Hezār Afsān (Persian: هزار افسان, A Thousand Tales), which in turn contained Indian elements.

Charting the timeline, English scholar, author and Sufi adept Robert Irwin has written: “In the 1880s and 1890s a lot of work was done on the Nights by Zotenberg and others, in the course of which a consensus view of the history of the text emerged. Most scholars agreed that the Nights was a composite work and that the earliest tales in it came from India and Persia. At some time, probably in the early 8th century, these tales were translated into Arabic under the title Alf Layla, or ‘The Thousand Nights’. This collection then formed the basis of The Thousand and One Nights. The original core of stories was quite small. Then, in Iraq in the 9th or 10th century, this original core had Arab stories added to it—among them some tales about the Caliph Harun al-Rashid. Also, perhaps from the 10th century onwards, previously independent sagas and story cycles were added to the compilation … Then, from the 13th century onwards, a further layer of stories was added in Syria and Egypt, many of these showing a preoccupation with sex, magic or low life. In the early modern period, yet more stories were added to the Egyptian collections so as to swell the bulk of the text sufficiently to bring its length up to the full 1,001 nights of storytelling promised by the book’s title”.

The Thousand And One Arabian Nights has been so appropriated by our culture that it is a de facto member of our so-called Western Canon. It is the source of so many of our fairy tales and boy’s own adventures with its magic lamps and genies, giant birds and winged horses, flying carpets and gorgeous girls in rich silks and ethereal damask. In our pubescent days, did we not “dream of Jeannie”?

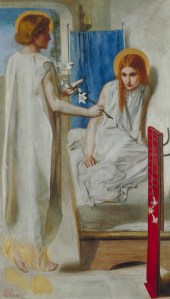

Harem pants and turbans, belly dancers and serpentine melodies, and a “nudge, nudge, wink, wink” of vicarious naughtiness (itself a word of Indian origin) – an exotic, “orientalist” retro-zeitgeist that drew artists, poets, writers and composers to this inexhaustible source of narrative, inspiration and titillation. Recall, back in those thankfully long gone more repressed days, the risqué, soft porn imaginings of European artists, including the Pre-Raphaelites and Orientalists who also elided into similar fever dreams of Babylonian and Roman erotica.

Musicians too got in on the act. In 1782, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart premiered Entführung aus dem Serail, The Abduction from the Seraglio, and Gioachino Rossini presented his L’italiana in Algeri or An Italian Girl in Algiers in 1813. These lightweight comic operas featured many of the tropes that entered the cinematic lexicon in the twentieth century, and whilst musically endearing and entertaining, their Orient was a mix of slapstick and exotic, and by today’s standards, condescending in their portrayal of lascivious sultans and their flunkies so easily outwitted by occidental heroes and heroines. Much grander and imposing is Russian composer Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov’s splendid Scheherazade suite, otherwise known as “the Sultan is coming”. There’s an orchestral rendering of this masterpiece below.

The stories rattle through English pantomimes, Hollywood fantasias, Walt Disney, and even the avant-garde Pier Paulo Pasolini: Alāʼu d-Dīn and Sindibādu l-Bahriyy (these were indeed their original names), Ali Baba and those bandits in huge pots – the inspiration and the storylines for all those boy gets girl cosplay, rom-com, adventure and fantasy films like The Thief of Baghdad and Prince of Persia, and musicals like Kismet – and many more besides, most of them ordinary and many, bad (go Google!). Baubles, bangles and beads indeed (see, below, the Clio from the film). It was a pleasant, picturesque oriental world, the Middle East as Hollywood imagined it before it hit the headlines with its oil, its tyrants, and it internecine wars, a world sans Hamas, Hezbollah, the Taliban, Da’ish and the Al Quds Brigade.

To illustrate the potential for satire, smut and downright silliness – a veritable “Carry on In The Casbah”. The nearest the famous British comedy series came to anything like this was the one film that didn’t have “Carry on” in its title: Follow That Camel in 1967. Though based on the French Foreign Legion adventures of Beau Geste, it doesn’t waste time getting to the suq and, predictably, the generic harem and the usual, well, carry on. Apropos this, there’s a clip below from the BBC production of British playwright Denis Potter’s excellent faux-musical Lipstick on Your Collar, set during the Suez Crisis of 1956, replete with orientalist imaginings and straight-out smut.

The spell of the orient also lured adventurers and chancers to the canyons and the castles, the deserts and the oases of the Levant, Mesopotamia, Persia, Afghanistan and India. And, I have to declare, yours truly – not without incident but no match for derring-do of Brits who went before. Like Irwin himself, I was of a generation with no more deserts to conquer, no fabled cities to administer. See Song of the Road (2) – The Accidental Traveller.

It’s a part of the world that has captivated much of my intellectual life for I too like many others before me was lured by the spell of the Orient.

I wrote before, in East, “I was drawn to the Middle East in another age, when it was the land of myth and magic, of dreamers and adventurers, of quixotic tilters at windmills, of pioneers who would make the deserts bloom, of dissemblers and deceivers bearing false promises. The ancient lands of the bible, the fabled realm of A Thousand and One Nights, and the restless quests of Richard Burton, Charles Doughty, and TE Lawrence. The pulp fiction fantasies of Frank Herbert, James Michener and Leon Uris, and the celluloid myths of Peter O’Toole, Omar Sharif, and Paul Newman”.

Middle East folk have taken to the stories too, and as in the West, it has inspired books, poems, plays and movies. Lebanese diva Fairuz played Scheherazade in a Beiruti musical back in the seventies, and Umm Kulthum, dead nearly five decades and still indisputably the Arab world’s most renowned and beloved singer, sang about the lass for forty minutes, which was not unusual for her, without saying too much about the story. There is a statue of Scheherazade and the sultan on the banks of the Tigris in Baghdad.

And yet, the whole glittering, fairytale artifice was built upon dubious foundations of misogyny and murder.

Scrumptious Scheherazade’s “cunning plan” was nothing more or less than that of distracting Shahriya, a randy psychopath of a sultan, from dispatching her (and her sister) – as he had done with his many short-lived exes. The premise is that his former missus cheated on him with a cavalcade of lovers, including slaves and persons of colour. To use the words of an old song by latter day philosopher Hal David and his sidekick Burt Bacharach,, he resolved that he was “never gonna love again”. And no doubt, in true oriental fashion, he was fearful of rival claimants and suspicious of all, including his paramours conspiring against him. Yet, he nonetheless constantly needs to get his end in. So whomsoever he selects to join him in his boudoir – and no one says no to the sultan – gets the chop the morning after. When Schezza gets the royal nod, she is determined not to go the way of her predecessors, and to preserve the lives of future bedmates. Accordingly, she keeps his lascivious lordship so distracted with her storytelling that he will refrain from slayage because he wants to hear how her tale ends. And yes, indeed, he forswears his murderous ways and settles into connubial bliss.

© Paul Hemphill 2024. All rights reserved

See also in In That Howling Infinite, A Middle East Miscellany

East is east and west is west

The term Orientalism gained its modern definition through the writing of the Palestinian academic and cultural critic Edward Said, especially his famous book Orientalism, published in 1978, which sparked controversy among scholars of Oriental studies, philosophy, and literature. It was a critique of cultural perceptions of how the Western world – primarily the white and Judeo-Christian world – perceives the East – or specifically lands and cultures that lie outside the borders of southern and southwestern Europe.

From a historical European perspective, the East has long been perceived as an unknown, alien, and, therefore, alluring world, that has existed for centuries, even millennia. The Greeks and Romans longed for the silk and spices of the East. To satisfy our human craving for the good things of life, busy trade routes stretched from China and Java to present-day Russia, Scandinavia, the Iberian Peninsula and the British Isles.

The term orient is derived from Latin, oriens meaning “east” (literally “sunrise”, from aurior, rising, and its geographical use of the word “rising” to refer to the east, where the sun rises). The term Levant is in turn derived from Old French, and Italian in origin, to refer to the lands of the rising sun – specifically the historical lands of Syria (in Roman times, specifically’ that included the modern states of Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, Israel, Palestine and most of Turkey. In its broad historical sense, it came to include Greece, the islands of the eastern Mediterranean, modern Egypt and North Africa. And with the emergence of European empires in the east, Persia, Afghanistan, India, China, and the East Indies.

Along with east, west, or west, derived, again, from Old French, via Latin, Occidentem, west, or “sky where the sun goes down”, as in occido, to go down or set, was originally synonymous with Christianity which in the Middle Ages were the states that followed the Roman Catholic faith and which for various centuries considered themselves superior to the Eastern Orthodox faith of the Byzantine Empire and the lands of Russia.

The Levant was widely used after the fifteenth century. During the two hundred years of the Crusades, during which the French knights and their retinue took control, the lands that became the crusader kingdoms were referred to as Outremer, meaning the lands beyond the sea. And through the Crusades, the love affair of Christian Europe with the East began. And it was to continue to this day, enchanting, seducing, and seducing soldiers, adventurers, travelers, troublemakers, writers, artists, and musicians.

Edward Said and Orientalism

Edward Wadih Said Edward Wadih Said (November 1935 – September 24, 2003) was a Professor of Literature at Columbia University, a public intellectual, and a founder of the academic field of Postcolonial Studies. A Palestinian-American born in Mandatory Palestine, he was a citizen of the United States through his father, a US Army veteran.

Educated in British and American schools, Said applied his pedagogical and cultural perspective to highlight the gaps of cultural and political understanding between the Western world and the Eastern world, especially with regard to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict in the Middle East.

As a public intellectual Said was a controversial member of the Palestinian National Council, due to his public criticism of Israel and Arab countries, especially the political and cultural policies of Islamic regimes that work against the national interests of their people. He called for the establishment of a Palestinian state to guarantee equal political and human rights for Palestinians in Israel, including the right to return to the homeland.

Orientalism in art history, literature, and cultural studies is the imitation or depiction of aspects of the Eastern world. These drawings are usually made by writers, designers, and artists from the Western world. In particular, Orientalist painting, more specifically depicting the ‘Middle East’, was one of the many disciplines of academic art in the nineteenth century, and the literature of Western countries showed a similar interest in Eastern themes.

Since the publication of Orientalism, much of academic discourse has begun to use the term “Orientalism” to refer to the generally nurturing Western attitude toward societies in the Middle East, Asia, and North Africa. In Said’s analysis, the West classifies these societies as static and undeveloped, thus creating a vision of Eastern culture that can be studied, photographed, and reproduced in the service of imperial power. Implicit in this is the idea that Western society is sophisticated, rational, flexible, and superior, Said writes.

His book redefines the term Orientalism to describe the Western tradition – academic and artistic – of biased interpretations of the Eastern world shaped by the cultural attitudes of European imperialism in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Said said that Orientalism as “the idea of representation is a theoretical idea: the Orient is a stage in which the whole of the Orient is confined” to make the Eastern world “less intimidating to the West.” And that the developed world, and the West in the first place, is the cause of colonialism, and that Western countries and their empires arose by exploiting backward countries and extracting wealth and labor from one country to another. Academically, the book has become a foundational text for postcolonial cultural studies.

While Said’s analysis relates to Orientalism in European literature, especially French literature, the historical view identified and described can also be applied to representations of the Orient in other art forms, including visual art – most notably in Orientalist painting, which was popular among artists And with galleries during the nineteenth century, which modern scholars see as depicting myth and fantasy that has little connection with reality, and also in other art forms that come like music and film.

Such representations drew criticism as much as before and after World War II, they perpetuated the imagined trend, giving generations of Westerners a distorted impression of the Middle East adorned with palm trees, minarets, and camels like illustrations of old chests of figs and boxes of Turkish delight and serpentine melodies. Such images directly connected in Western minds with the trappings of orientalists.

Fun, romantic and fascinating, this Middle East as imagined by artists and Hollywood – to quote from above, “harem pants and turbans, belly dancers and serpentine melodies, and a “nudge, nudge, wink, wink” of vicarious naughtiness (itself a word of Indian origin) an exotic, “orientalist” retro- zeitgeist that drew artists, poets, writers and composers to this inexhaustible source of narrative, inspiration and titillation”.

Inevitably, a backlash arose in the developing world, both in the Islamic world, and in Asian and African countries in general, and the term Western is now often used to refer to the negative views of the Western world found in Eastern societies, and is based on the nationalism that spread as a response to colonialism. Furthermore, Edward Said himself has been accused of Westernizing the West in his critique of Orientalism. He is guilty of falsely describing the West in the same way that Western scholars are accused of falsely describing the East. Said is said to have encouraged a homogenous picture of the West, which no longer consisted not only of Europe, but also of the United States, Canada and Australia which became more culturally influential over the years.

[This profile of Edward Said and Orientalistism is drawn largely from Wikipedia. For an interesting account of Robert Irwin’s take down of Said’s opus, see The man who defeated Orientalism The man who defended Orientalism]