It’s the Land, it is our wisdom

It’s the Land, it shines us through

It’s the Land, it feeds our children

It’s the Land, you cannot own the Land

The Land owns you

Dougie McLean, Solid Ground

This is a story about the land – and the people who have reside thereupon.

Scottish folksinger Dougie McLean’s verse captures exactly its ethos: of the land as relational, ancestral, and moral; of belonging as stewardship rather than conquest; of identity entwined with place rather than imposed upon it. “You cannot own the Land – the Land owns you” resonates with what we are about to write about overlapping inheritances, continuity, and indigeneity. The verse gives us a lyrical bearing: it allows us to frame Jewish and Palestinian attachment to the land not as a contest of exclusive ownership, but as overlapping, reciprocal, and living relationships. It legitimises the presence of both without forcing a zero-sum moral calculus.

Forward: the Myth of Fingerprints

Watching the coverage of the Gaza war – in mainstream commentary, on social media, in slogans chanted half a world away – In That Howling Infinite was struck less by passion than by historical amnesia. Dates collapsed into each other. 1948 was invoked without 1917. 1967 without 1948. 2023 without Ottoman decline, Mandate ambiguity, imperial cartography, demographic upheaval. Archaeology was dismissed as propaganda; genealogy as myth; continuity as invention. A century was compressed into a headline; millennia into a meme.

We prefer our tragedies forensic.

Modern political culture trains us to search for a single print on the glass – the moment, the document, the leader, the decision that explains everything. We want the smudge that proves who began it, who bears the primal guilt, who stands at the origin of the wound. A history with fingerprints is reassuring. It suggests that if only one actor had behaved differently – one declaration withheld, one militia restrained, one settlement not built, one massacre not committed – the catastrophe might have been avoided.

But the history of Israel and Palestine does not yield to forensic neatness.

There is no solitary fingerprint pressed into this soil. Not Balfour’s, nor Lloyd George’s. Not Haj Amin al-Husseini’s, nor Ben-Gurion’s. Not Nasser’s, not Arafat’s, not Sharon’s, not Netanyahu’s, not Hamas’s. No single impression explains the pattern. The land bears instead a dense overlay of smudged prints: empire and partition, fear and ambition, miscalculation and opportunism, exile and return, massacre and reprisal, daring and folly. Each generation has added its own layer. Each act has generated reaction; each reaction has hardened into structure; each structure has constrained the next set of choices.

The myth of fingerprints flatters our appetite for moral certainty. It allows us to say: there — that was the sin; there – that is the villain. It relieves us of complexity. It permits outrage without introspection. It offers altitude without clarity.

Yet this conflict is cumulative. The Nakba did not occur in a vacuum. Nor did the wars that followed. Nor did the Occupation arise ex nihilo. Nor did Palestinian rejectionism or Israeli settlement expansion spring from pure malice detached from context. Nor did October 7 erupt without genealogy – however indefensible its brutality, however catastrophic its consequences. Each event is entangled with what preceded it and what followed after. Violence here is not a fingerprint; it is a palimpsest.

To say this is not to dissolve accountability. It is to resist reductionism. It is to refuse the consolations of moral monoculture – the narrowing of empathy into a single authorised grief, the shaping of facts to fit feelings, the retreat into what I have elsewhere called the box canyon of certainty. Intellectual honesty demands a more difficult posture: to hold multiple truths in tension without collapsing them into equivalence.

This land — like any homeland, like any “country” in the deeper sense First Nations Australians use the word – holds layered attachment. It holds Jewish longing and Palestinian dispossession; British imperial design and Arab nationalist pride; secular aspiration and religious revival; survival strategy and ideological fervour. None alone explains the whole. Together they form the sediment of a century.

If this essay resists simple answers, it is because the land itself resists them. What follows is not an argument for neutrality, nor a plea for bloodless detachment. It is an attempt to describe historical continuity in a place where memory is weaponised and identity compressed into accusation. It is written in the hope – perhaps naïve, perhaps stubborn – that understanding genealogy, archaeology, chronology, and context might slow the reflex to eliminate rather than to comprehend.

There are no clean fingerprints here. Only accumulated traces.

And the work begins by learning to see them all.

Embrace the Middle East, Sliman Mansour

Before you begin …

There is a temptation, with this land, to search for fingerprints. To press the soil for a single impression and declare: “Here – here is where it began. Here is the trespass. Here is the theft. Here is the wound from which every other wound must have flowed”. But the ground does not yield so easily. It holds not one print, but many, layered and half-erased – footsteps crossing footsteps, prayers rising from ruins, stones reused and renamed. It is less a crime scene than a palimpsest: written, scraped back, written again though the old script never fully disappears.

This essay begins there. It moves slowly, because the history moves slowly. Jewish civilisation is not incidental to this terrain; it was formed there, fractured there, remembered there in exile for two millennia through liturgy and law and longing. Nor are Palestinians latecomers to their own homes; their belonging is carried in olive groves and family deeds, in village names, in the memory of 1948 spoken not as theory but as rupture.

Two continuities. Uneven in power, different in structure, but real.

Modern nationalism – that restless 19th- and 20th-century force – took older forms of attachment and hardened them into programs. Zionism emerged from European peril and Jewish memory; Palestinian nationalism emerged from Ottoman dissolution and local rootedness. Empire intervened. War intervened. Fear intervened. What might once have overlapped became mutually exclusive.

The language we now reach for – settler colonialism, indigeneity, apartheid – illuminates some contours and obscures others. These frameworks explain structures of domination, especially in the territories occupied since 1967. Yet they often falter before the stubborn fact of Jewish historical continuity. When analysis becomes catechism, history flattens; complexity is treated as betrayal.

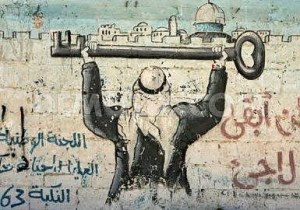

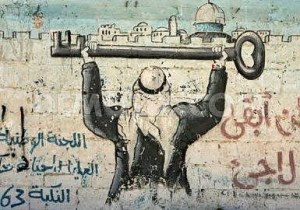

At the centre of the essay stand two words that mirror each other across the decades: Aliyah and al-‘Awda. Return and return. Ascent and homecoming. One largely realised in the sovereignty of a state; the other deferred, carried as al Muftah, the key, and inheritance. These are not merely political claims. They are existential longings. Each fears that recognising the other threatens its own legitimacy. Each is haunted by absence.

And then there is the present – October 7 2023, and the devastating war that it precipitated, and the shattering of whatever fragile equilibrium once existed. Trauma does not cancel trauma; it compounds it. Israeli politics hardens toward security and annexationist imagination. Palestinian politics fragments, with religion filling the vacuum left by exhausted secular promises. The two-state solution lingers like a map no longer consulted but not yet discarded.

This is not a plea for neutrality. Nor is it a ritual balancing of grief. Power asymmetries are real. Civilian suffering is real. So too is the danger of moral monoculture – the insistence that only one story counts, only one inheritance is authentic, only one people may speak in the language of belonging.

The land between the river and the sea has never held a single narrative. It carries more than one continuity, more than one exile, more than one claim to home. Any future worth imagining must begin by resisting erasure — of Jews, of Palestinians, of history itself.

If the essay asks anything of the reader, it is patience. A willingness to sit with more than one truth at once. A willingness to see that complexity is not evasion but reality.

The soil remembers more than we do. Are we prepared to remember with it?

Why we have written this story

This long essay was born less out of certainty than unease.

In the months following October 7 2023 and the Gaza war that followed, lasting two years and yet unresolved, we found ourselves increasingly disheartened – not only by the violence itself, but by the impoverished historical literacy that now dominates much of the public conversation. In mainstream commentary and across social media, Israel–Palestine is routinely reduced to slogans, memes, and moral shortcuts: 1948 as original sin, or 1967 as sole reference point, or 2023 as rupture unmoored from everything that came before. The deeper history – the Ottoman centuries, the layered genealogies, the archaeology underfoot, the long coexistence and long frictions of peoples and faiths – is treated as dispensable, even suspect. Ignorance is worn as conviction.

This narrowing of historical vision has consequences. It breeds existentialist and eliminationist rhetoric on all sides: claims that one people is fabricated, the other uniquely criminal; that history itself can be annulled by denunciation. It flattens complex inheritances into moral caricature, and in doing so accelerates a global coarsening of discourse – one that has travelled far beyond the region, seeding division, hatred, and a hardening of hearts across societies that once imagined themselves distant observers.

Our purpose here is modest but insistent. We want to describe, as clearly and simply as possible, the historical continuity of both Israel and Palestine: how peoples persist, inherit, adapt, and remain attached to land across conquest, conversion, exile, and return. I want to show that the land has never been empty, never singular, never owned by one story alone. And I want to counter the moral monoculture that insists this conflict can be understood, let alone solved through absolutes.

This essay does not argue for innocence. It argues against erasure. It is not an argument against passion, nor a plea for bloodless neutrality. It is written in resistance to the idea that complexity is a form of evasion, or that empathy is betrayal. If it insists on anything, it is that history matters – and that without it, moral seriousness quickly curdles into moral certainty, and certainty into something far more dangerous. A lot of intellectual labour is required to stand on what we like to call the high ground without mistaking altitude for clarity.

As for the position of In That Howling Infinite on Israel, Palestine, and the Gaza war, it is neither declarative nor devotional; it is diagnostic. Inclined – by background, training, temperament, and long engagement with the region – to hold multiple truths in tension, it seeks to see, as the song has it, the whole of the moon. It is less interested in purity than in resisting moral monoculture and the consolations of unanimity. That stance does not claim wisdom. It claims only a refusal to outsource judgment, and a suspicion of movements that confuse volume with truth.

On Zionism, this essay treats it not as a slogan but as a historical fact with moral weight: the assertion – hard-won, contingent, flawed – that Jews are entitled to collective political existence on the same terms as other peoples. In this limited but essential sense, this blog is Zionist. It does not sanctify Israeli policy, excuse occupation, or romanticise state power. But it rejects the sleight of hand by which Israel’s existence is transformed from a political reality into a metaphysical crime – an expectation uniquely imposed upon Jews, and demanded of no other nation: justification for being.

On anti-Zionism, it is unsparing. Not because criticism of Israel is illegitimate – on the contrary, it is necessary – but because anti-Zionism increasingly operates as a categorical refusal to accept Jewish collective self-determination at all. What troubles us most is not its anger, but its certainty: its indifference to history, its appetite for erasure, its readiness to recycle older antisemitic patterns – collective guilt, inversion of victimhood, the portrayal of Jews as uniquely malignant actors – while insisting, with studied innocence, that Jews are not the subject. If not always antisemitism outright, the line separating the two is wafer-thin, and too often crossed.

At the same time, this essay is deeply critical of Israeli power: of occupation, settlement, annexationist fantasy, and the moral corrosion of permanent domination. It takes seriously the Palestinian experience of dispossession, fragmentation, humiliation, and despair – and the ways in which those conditions have fostered not only resistance, but radicalisation, sacralisation, and a narrowing of political imagination.

October 7 stands as a grim hinge. It has not only set back any prospect of reconciliation between Israelis and Palestinians for a generation; it has unleashed a wider contagion – one that has coarsened global discourse, legitimised eliminationist language, and normalised the idea that complexity itself is suspect. As Warren Zevon warned, “the hurt gets worse, and the heart gets harder”.

This essay is written against that hardening. It asks whether it is still possible to think historically, ethically, and imaginatively about a land claimed by more than one people – and whether refusing moral certainty might yet be an act not of evasion, but of responsibility.

The sections that follow are designed to stand alone and to accumulate. Each may be read independently; together they form a single, unfolding argument. If certain themes recur, that is intentional. The history under discussion does not advance in straight lines but circles back, reappears, and insists upon reconsideration. The structure mirrors the subject. Repetition here is not redundancy, but return.

It is a long read, because there is much that must be said. For readers who are time-poor, what follows is a brief précis – enough, I hope, to give you the outline, and perhaps to tempt you further.

Beginnings … Naming and Continuity

If there is a place to begin, it is not with a verdict but with a name.

Names are where history first hardens into meaning. They signal continuity or rupture, belonging or exclusion, memory or erasure. In this land especially, names do not merely describe; they contend. They carry sedimented layers of empire, scripture, conquest, pilgrimage, and return. To name is already to argue – but to refuse names altogether is also to argue, and more crudely.

One of the great distortions in contemporary debate is the insistence that political legitimacy must rest on administrative tidiness: that because the Ottomans did not govern a province called “Palestine,” Palestine did not exist; or conversely, that because modern Zionism emerged in Europe, Jewish attachment to the land is a late invention rather than an ancient continuity. Both claims mistake bureaucracy for belonging, paperwork for peoplehood. Both treat history as a courtroom exhibit rather than a lived inheritance.

What endures instead – often inconveniently – is continuity without sovereignty: peoples who remain present without power, attached without permission, named and renamed by others but never entirely erased. Jews prayed toward this land long before they could govern it. Palestinians inhabited it long before they could claim it politically. Neither experience cancels the other. Both are real. Both are incomplete on their own.

To understand how these parallel attachments hardened into mutually exclusive claims requires moving slowly, historically, and without the false comfort of absolutes. It requires tracing how a land administered by empires became a land imagined by nations; how religious memory became political project; how return – Aliyah for Jews, al-‘Awda for Palestinians – came to function not merely as aspiration but as moral horizon. It also requires acknowledging how each side’s story, when pressed by trauma and fear, learned to deny the depth of the other’s.

What follows, then, is not a search for origins that absolve, but for continuities that explain. Not a competition of suffering, but an examination of how attachment becomes destiny – and how destiny, when absolutised, forecloses imagination.

The story begins, as so many arguments do, with the claim that there was “no Palestine.” And with the equal and opposite insistence that there was no Jewish return – only intrusion. Both are wrong. Both are revealing. And both point us, inevitably, to the longer history that neither slogan can contain.

The claim that “Palestinians were here before Jews” is historically imprecise – but so is the claim that Jewish antiquity erases Palestinian presence. Both are simplifications, moral absolutes that flatten centuries of layered reality into slogans. The land between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean has been inhabited continuously for millennia, by overlapping peoples, faiths, and cultures.

Jewish civilisation has deep roots here, attested by archaeology, scripture, ritual, and memory. Cities such as Jerusalem, Hebron, Shechem, Jericho, Gaza, and Jaffa are not abstractions – they are places woven into law, worship, settlement, and daily life across time, repeatedly reoccupied, referenced, and remembered. Yet these same cities have been continuously inhabited by non-Jewish populations, who over centuries became Christian, Muslim, Arabic-speaking, and eventually Palestinian in identity. The Arabic place-names that survive – Nablus, Al-Khalil, Silwan, Yafa – often preserve Hebrew, Aramaic, Greek, or Latin forms, just as London preserves its Roman past or Paris its Gaulish echoes. Continuity in place is not ownership; inheritance is layered, overlapping, and sometimes contested.

The Roman renaming of Judea as Syria Palaestina was a gesture of imperial punishment, yet even this act of erasure could not erase lived reality. Centuries later, European travelers, missionaries, cartographers, and strategists reanimated the name “Palestine,” overlaying the land with biblical imagination, imperial calculation, and the romance of Orientalism. European frameworks – strategic, moral, and aesthetic – shaped modern political consciousness long before modern political actors arrived. The Europeanisation of the Holy Land created a template into which both Jewish and Arab claims would later be poured, each seeking legitimacy and recognition.

This essay traces these interwoven threads. It begins with the names themselves – the enduring markers of settlement, memory, and linguistic survival. From there, it examines continuity and archaeological evidence, showing how material culture and living communities intersect in ways that defy simple claims of precedence. It then moves to the language of settler colonialism and the frameworks imported from European empire, exposing how interpretive categories can be mobilised to delegitimise or moralise historical presence. Finally, it engages with indigeneity – not as a racial or ethnic label, but as a language of connection, survival, and attachment to place – demonstrating how both Jewish and Palestinian identities are inseparable from the soil, the history, and the lived landscape of the land.

History here does not grant exclusive ownership. It grants memory, attachment, and responsibility. The tragedy – and the challenge – is that two peoples trace their histories into the same soil, each with legitimate claims, each bearing inherited trauma, and each constrained by a political struggle that too often demands a single story. This essay does not promise resolution. It seeks reflection: to trace the layers, to illuminate the overlaps, and to hold complexity without collapsing it into certainty.

The return of “Palestine”: naming, memory, and the politics of inheritance

One of the more persistent confusions in contemporary debate is the claim – often made with an air of finality – that “Palestine” is either an ancient, uninterrupted political reality or a wholly modern invention, conjured out of thin air in the twentieth century. Both positions flatten history into a moral ordering exercise: one name authentic, the other fraudulent; one memory legitimate, the other contrived. This is precisely how historical argument slips into a box canyon, where complexity is mistaken for weakness and certainty for truth.

The Ottoman Empire, which ruled the region from the early sixteenth century until the First World War, did not govern a province called Palestine. Its administrative logic was practical rather than symbolic. The land between the Mediterranean and the Jordan was divided among the Eyalet (later Vilayet) of Damascus, the Vilayet of Beirut, and, from 1872, the Mutasarrifate of Jerusalem, which reported directly to Istanbul. Taxes, conscription, roads, and security mattered; biblical resonance did not. In that narrow bureaucratic sense, “Palestine” did not exist.

But absence from an imperium is not the same thing as absence from historical memory. The name Palestine never vanished. It persisted in European cartography, in Christian pilgrimage literature, in Islamic geographical writing as part of Bilad al-Sham, and in the loose regional vocabulary used by locals themselves, locals who belonged to a variety of ethnicities and faiths. It survived as a cultural and geographic term rather than a sovereign one. This distinction – between administrative reality and historical imagination – is often ignored, and much mischief flows from that omission.

The decisive shift came not from Istanbul, but from Europe. From the late eighteenth century onward, the eastern Mediterranean became an object of renewed European attention. The Ottoman Empire was weakening; Britain, France, Russia, and later Germany were probing for influence. Strategic considerations – sea routes, land bridges, ports, and imperial rivalry – pulled the region into a new geopolitical frame. “Palestine” proved a convenient and evocative name for this space: recognisable, resonant, and already embedded in European mental maps.

Religion deepened this re-engagement. For European Christians, especially Protestants, Palestine was not merely a territory but the word made flesh – the physical stage of the Bible. Missionaries, biblical scholars, archaeologists, and pilgrims flooded the region in the nineteenth century. Guidebooks, maps, and sermons revived biblical place-names and overlaid them onto a living landscape. The land was read as Scripture, and Scripture was projected back onto the land. Ottoman administrative divisions were quietly bypassed in favour of a vocabulary saturated with sacred history.

This religious lens blended seamlessly with the romance of Orientalism. Painters, travel writers, and antiquarians portrayed Palestine as timeless, unchanging, and curiously suspended outside modern history. Its inhabitants appeared as figures in a tableau – colourful, ancient, but politically inert. Europe “rediscovered” Palestine by freezing it in a biblical past, a move that simultaneously elevated the land’s symbolic value and erased the modern lives unfolding upon it. Historical memory was curated selectively, with some layers illuminated and others dimmed. [In In That Howling Infinite, see Alf Layla wa Laylah – the Orient and Orientalism]

Commerce and infrastructure reinforced this process. Steamships, railways, ports, and telegraph lines tied the region more tightly to Europe. Consuls, traders, and investors spoke of Palestine as a commercial and logistical unit. The term functioned as a brand – useful, intelligible, and already freighted with meaning. Still, this was not sovereignty. It was recognition through repetition.

The First World War transformed repetition into authority. British leaders did not speak of conquering Ottoman districts; they spoke of liberating Palestine. This choice of language was not accidental. British Prime Minister David Lloyd George, a son of the Welsh chapel and steeped in biblical culture, understood the land through Scripture as much as strategy. Jerusalem mattered to him symbolically, almost providentially. The term “Palestine” resonated with the British public, aligned with long-standing European usage, and wrapped military objectives in moral narrative. In naming, power announced itself. [Regarding the Balfour Declaration, which we will come to later, see In That Howling Infinite‘s The hand that signed the paper]

The British Mandate formalised what European imagination had long rehearsed. “Palestine” became a legal entity under international law. The name appeared on stamps, coins, and passports, rendered in Arabic (Filastin) and Hebrew (Eretz-Yisrael (Palestina)). Zionist institutions were legally Palestinian; Arab inhabitants were administratively Palestinian. Only later, as national conflict sharpened, did the term become a site of rejection and contestation. What began as an externally imposed administrative label was gradually inhabited as an identity by those who lived within its bounds. [In In That Howling Infinite, see The first Intifada … Palestine 1936]

None of this means that Palestinian identity was invented wholesale by Europeans, nor that Jewish historical connection to the land is diminished or negotiable. It means something more uncomfortable and more human: that modern political identities often crystallise under pressure, shaped by imperial power, local experience, and inherited memory alike. To declare one authentic and the other fraudulent is to impose a moral hierarchy onto history itself, a hierarchy confounds understanding.

Here, the danger is not ignorance but moral certainty. Historical memory becomes a sorting mechanism: ancient equals legitimate, modern equals suspect; one story accumulates moral credit, the other moral debt. This is how history is quietly recruited into a hierarchy of hostility – not through overt hatred, but through the denial of standing. Once a people’s name is dismissed as an invention, their claims can be treated as optional.

The harder truth is that Palestine returned to political life not because the Ottomans named it, nor because Europeans fabricated it ex nihilo, but because European power needed a name that carried biblical gravity, strategic clarity, and cultural familiarity. That name was then lived into – contested, resisted, embraced, and redefined – by the people on the ground. Modernity did the rest.

History here does not issue verdicts. It records inheritances – some ancient, some imposed, some painfully recent. When we try to force it into a moral ordering system, we lose precisely what makes it useful: its capacity to show how overlapping memories can coexist long before they are weaponised against one another.

Continuity, inheritance, and the limits of proof

Few arguments in this conflict are deployed with more confidence – and less care – than the appeal to ancient place names. Lists are recited, verses quoted, etymologies traced with forensic zeal, and the conclusion announced as if self-evident: the names are Hebrew, therefore the land is Jewish; the Arabic forms are later, therefore derivative. Continuity is treated as ownership, and inheritance as exclusivity. History is reduced to a ledger.

The facts themselves are rarely in dispute. Many of the region’s towns and cities bear names that can be traced deep into antiquity, and many of those names appear in the Hebrew Bible. Shechem becomes Neapolis under Rome and Nablus in Arabic. Hebron becomes al-Khalil, preserving Abraham’s epithet, “the Friend.” Shiloah echoes in Silwan; Jaffa in Yafa; Gaza in Ghazza; Jericho in Ariha. Even where the phonetics shift, the bones of the name remain. Language remembers.

What this demonstrates – powerfully and legitimately – is continuity of place. These are not invented towns dropped onto an empty map. They are inhabited sites with long, layered histories, revisited, renamed, translated, and repurposed by successive cultures. The land has not been erased and rebooted; it has been overwritten, like a palimpsest, with earlier texts still faintly visible beneath the newer script.

But continuity of place is not the same thing as continuity of people, and neither is the same as political entitlement. Names travel across languages precisely because populations change while places endure. Arabic, like English, routinely absorbs older toponyms rather than replacing them wholesale. London keeps its Roman core; Paris its Gallic one; Istanbul carries Byzantium in its shadow. No one imagines that linguistic survival alone settles questions of sovereignty.

The Hebrew Bible is an indispensable historical source, but it is also a theological text. When biblical names are cited as proof, the argument quietly shifts registers – from history to sacred memory. That shift is not illegitimate, but it must be acknowledged. For Jews, these names encode ancestral attachment, ritual meaning, and historical consciousness. They are part of a civilisational inheritance. To deny that is dishonest.

Yet it is equally dishonest to pretend that the later Arabic names represent rupture rather than translation. Al-Khalil does not erase Hebron; it reframes it through another religious lens that also venerates Abraham. Yafa does not cancel Jaffa; it carries it forward in a new linguistic register. In many cases, Arabic usage preserved ancient names when European empires and modern nationalisms might have flattened them. [See In That Howling Infinite, Children of Abraham, a story of Hebron]

This is where the argument often slips into a moral ordering exercise. Ancient becomes authentic; later becomes suspect. One inheritance is elevated as original, the other demoted as parasitic. But history is not a queue where the first arrival gets eternal priority. It is an accumulation of lives lived in the same places under changing conditions, languages, and powers.

Archaeology reinforces this layered reality rather than resolving it. Jewish ritual baths, Hebrew inscriptions, coins, winepresses and mikvas – these are real and abundant. So too are churches, mosques, monasteries, Islamic endowments, and centuries of continuous habitation by Arabic-speaking communities. The soil, the rocks, the bricks do not adjudicate; they record.

The mistake is not in pointing out Hebrew origins. The mistake is in imagining that etymology can do moral work it was never designed to perform. Place names testify to historical depth, not to exclusive possession. They tell us that people came, stayed, left, returned, converted, translated, adapted – and named what they loved in the language they spoke.

Inheritance, in this sense, is not a single line of descent but a woven one. Jews inherit these names as memory and longing; Palestinians inherit them as lived geography and daily speech. Both inherit them honestly. Conflict arises when inheritance is mistaken for cancellation – when one story is told in order to invalidate the other.

Used carefully, place names can rescue us from the fantasy of emptiness and the lie of discontinuity. Used carelessly, they become weapons of erasure, enlisted in a hierarchy of legitimacy that history itself does not recognise. That is the box canyon: mistaking linguistic survival for moral verdict.

Names endure because people endure. The tragedy is not that the land has too many names, but that its names have been asked to carry a burden they were never meant to bear.

Settler Colonialism and the European frame: a theory migrates

The Europeanisation of the Holy Land in the nineteenth century created a template into which both Jewish and Arab claims would later be poured, each seeking recognition, legitimacy, and moral validation. Modern debates over “settler colonialism” reflect this European lens.

The contemporary description of Israel as a “settler-colonial” project did not arise organically from the Ottoman or even early Mandate experience of the land. It is a later interpretive overlay, shaped by intellectual currents that themselves emerged from Europe’s reckoning with empire. Like the modern political revival of the name “Palestine,” the settler-colonial frame is best understood not as an invention ex nihilo, but as a concept imported, adapted, and weaponised under particular historical pressures.

Settler colonialism, as a theory, was developed to explain societies such as Australia, the United States, Canada, and New Zealand – places where European settlers crossed oceans, displaced Indigenous populations, and sought not merely to rule but to replace. Its defining features are familiar: elimination rather than exploitation, permanence rather than extraction, the transformation of land into property, and the erasure – physical or cultural – of prior inhabitants. It is a powerful lens, forged in the moral aftermath of European expansion and decolonisation.

When this framework is applied to Israel, it draws much of its force from the earlier Europeanisation of Palestine itself. Once the land was reconceived through European strategic, biblical, and Orientalist eyes – as a space legible primarily to Western moral categories – it became available for reclassification within Europe’s own moral inventory. Palestine, first imagined as a biblical landscape awaiting modern administration, later became recast as a colonial theatre awaiting decolonial judgement.

The argument runs roughly as follows: Zionism was a European movement; European Jews migrated to Palestine; the project relied on imperial sponsorship; therefore Israel is a settler-colonial state. The clarity of this syllogism is precisely what makes it attractive – and what makes it misleading. It collapses different historical phenomena into a single moral category, flattening motives, origins, and outcomes into a single narrative of invasion and replacement.

What this framing often overlooks is that Zionism did not emerge from imperial confidence but from European catastrophe. Jews were not agents of a confident metropole exporting surplus population; they were refugees, outcasts, and survivors of a continent that had repeatedly expelled or exterminated them. The first Jewish arrivals were fleeing from pogroms in Poland and Ukraine. Their relationship to Europe was not one of imperial extension but of repudiation. To describe this as simply another European colonial venture is to read Jewish history backwards through a framework designed for very different cases.

At the same time, the settler-colonial critique persists because it names something real: the experience of dispossession endured by Arab Palestinians. Land was acquired, institutions were built, borders were enforced, and a new sovereign order emerged that many inhabitants experienced as imposed rather than negotiated. For Palestinians, the language of settler colonialism offers a way to translate loss into a globally recognisable moral grammar – one that resonates with other Indigenous and postcolonial struggles. In this sense, it functions less as a precise historical diagnosis than as a political vernacular of grievance.

Right-wing Israeli nationalists deploy antiquity and indigeneity to delegitimise Palestinian claims, presenting Arab presence as late, derivative, or contingent. The settler-colonial argument, in turn, delegitimises Jewish political presence by recoding it as foreign, European, and imposed. Each side selects a different temporal starting point and treats it as dispositive. Each claims history as an audit rather than an inheritance.

The danger lies in how quickly these frameworks harden into moral absolutes. Once Israel is defined as a settler-colonial state, its existence becomes a standing injustice rather than a contested reality. Decolonisation, in this register, cannot mean reform, compromise, or coexistence; it implies undoing. Conversely, once Palestinian identity is dismissed as a colonial by-product or an invention of the Mandate, Palestinian claims become negotiable at best, disposable at worst.

It is no accident that the settler-colonial frame gains traction in Western academic and activist spaces. It speaks in a language those spaces already know – one shaped by Europe’s own reckoning with empire, race, and guilt. Israel, long cast as a European outpost in the Middle East, fits neatly into this moral template. The irony is sharp: a people once excluded from Europe are now condemned as its agents.

None of this requires denying the realities of occupation, inequality, or Palestinian suffering. But it does require recognising that “settler colonialism” is not a neutral descriptor. It is a polemical category, one that orders history toward a conclusion. It answers the question before it is fully asked.

The tragedy of this debate is not that the concept is used, but that it is used as a final word rather than a starting point. When theory becomes destiny, politics becomes theology. The conflict is no longer about borders, rights, or security, but about moral existence itself.

In that sense, the settler-colonial argument is less an explanation of Israel–Palestine than a continuation of the same European framing that once reimagined the land as “Palestine” in the first place: a tendency to see the region primarily through Western categories, whether biblical or decolonial, and to sort its inhabitants accordingly.

History here resists clean typologies. It offers no immaculate victims and no unblemished founders. What it offers instead is a warning: when legitimacy is treated as a finite resource, history becomes a courtroom and memory a weapon. That is how arguments meant to liberate end up reproducing the very logic they oppose.

Indigeneity and the struggle for moral standing

In contemporary debates over Israel and Palestine, few terms carry as much moral voltage – and as much conceptual confusion – as indigeneity. Borrowed from global struggles against colonial domination, the term now circulates as a claim to moral priority: to be indigenous is to possess an ethical standing that precedes politics, a legitimacy that demands recognition rather than negotiation. But like “Palestine” and “settler colonialism,” indigeneity is not a timeless category. It is a modern political language, forged in response to empire, and its application to the Levant reveals as much about contemporary moral frameworks as it does about ancient history.

At its core, indigeneity refers not simply to being “there first,” nor to race or bloodline, but to historical continuity with pre-colonial societies, to distinct cultural and linguistic traditions, and to a sustained relationship – often spiritual as much as economic – with a particular land. It is a global identity, articulated most forcefully by peoples confronting or surviving colonial domination, and it centres resistance to dispossession rather than mere antiquity.

This definition already exposes the difficulty. The land between the Jordan and the Mediterranean is not a blank slate upon which a single indigenous identity can be inscribed. It is one of the most continuously inhabited regions on earth, layered with successive empires, religions, and populations. Pre-colonial, in this context, depends entirely on where one chooses to begin the clock.

Jewish claims to indigeneity rest on several pillars: ancient presence, religious centrality, continuous textual and ritual attachment, and demonstrable archaeological record. Judaism is not merely a faith but a civilisation rooted in a specific land, with laws, festivals, and narratives oriented toward it. Even after exile, Jewish life remained geographically tethered to the land, to Zion, through prayer, pilgrimage, and memory. Return was not a metaphor but a liturgical expectation. In this sense, Jewish indigeneity is civilisational rather than demographic – maintained across time even when population density fluctuated.

Arab Palestinian claims, by contrast, emphasise continuous physical presence and lived inheritance. Generations cultivated the land, built villages, spoke local dialects, and developed social and religious institutions in situ. Their indigeneity is experiential rather than textual, grounded in daily life rather than eschatological hope. For Palestinians, the land was not a promise deferred but a home inhabited. Dispossession, when it came, was not a theological wound but a practical and immediate one.

Both claims fit parts of the global indigeneity definition – and neither fits it perfectly. Jews are indigenous in origin but diasporic in history; Palestinians are indigenous in continuity but historically shaped by Arabisation and Islamisation, processes that themselves followed earlier imperial expansions. To insist that one of these realities cancels the other is to misunderstand what indigeneity was meant to do.

Here is where the concept begins to deform under polemical pressure. External supporters – particularly in Western activist and academic spaces – often import indigeneity frameworks developed in the Americas or Australasia and apply them mechanically to the Levant. In those contexts, the moral geometry is clearer: a distant metropole, a settler population, an indigenous society pushed to the margins. Israel–Palestine does not conform to that template, yet the language is seductive because it promises moral clarity.

Thus Jews are cast as non-indigenous Europeans, despite the Middle Eastern origins of Jewish civilisation and the presence of large Mizrahi or Eastern Jewish populations whose histories cannot be reduced to Europe. Palestinians are cast as indigenous in a singular, exclusive sense, despite the region’s long history of migration, conversion, and cultural fusion. Each simplification flatters one side while erasing inconvenient facts on the other.

What emerges is a competition for moral standing rather than a serious engagement with history. Indigeneity becomes a zero-sum status: to recognise one claim is assumed to invalidate the other. This is the same logic we have seen with place names and settler colonialism – a moral ordering of history that ranks suffering and legitimacy rather than seeking coexistence.

The irony is that indigeneity, as a global concept, was meant to protect vulnerable peoples from erasure, not to authorise it. Its ethical force lies in resisting domination and dispossession, not in adjudicating which people has the superior claim to a land saturated with overlapping inheritances.

In the Levant, indigeneity is best understood not as a verdict but as a condition: multiple communities, each with deep roots, each shaped by conquest and survival, each bearing legitimate attachments that cannot be reduced to slogans. Jews did not arrive as strangers to a foreign land; Palestinians did not materialise as historical afterthoughts. Both are native to the story of the place, even if they entered different chapters at different times.

When indigeneity is pressed into service as a weapon, it joins the hierarchy of malice and hostility – not through open hatred, but through the quiet withdrawal of legitimacy. One people’s history is declared foundational; the other’s is recoded as contingent. Once that move is made, compromise begins to look like betrayal, and coexistence like moral failure.

The harder, and more honest, conclusion is also the less satisfying one: indigeneity here does not resolve the conflict. It explains why it is so difficult to resolve. The land is not contested because one people lacks roots, but because too many roots run too deep, too close together, and too painfully intertwined.

That recognition does not end the argument. But it does prevent it from becoming a theology – where history is scripture, identity is fate, and politics is reduced to exegesis.

Beyond religion and race: peoples, continuity, and a multiplicity of origins

A persistent misconception in discussions of the Levant is the urge to reduce its peoples to singular categories: Judaism treated as merely a religion; Palestinians treated as a race. Both simplifications obscure far more than they explain. Jewish and Palestinian identities are not fixed or monolithic; they are composite formations – layers of ancestry, culture, language, belief, and historical experience accumulated over millennia.

Judaism undeniably carries a religious dimension, but it has never been only a matter of faith. It is also an ethnic and civilisational identity, sustained across time through shared law, memory, ritual, and a sense of common origin. Even in dispersion, Jewish communities retained continuity – cultural, linguistic, and symbolic – with the Levant. Genetic studies reinforce this historical record: many Jewish populations share markers linking them to the broader Levantine gene pool, interwoven, inevitably, with the DNA of the regions where they lived for centuries. Jewish identity, then, is simultaneously ancestral and diasporic, religious and biological, local in origin and global in experience.

Palestinian identity is no less complex. Palestinians are not a singular race, but the inheritors of continuous habitation shaped by centuries of settlement, cultivation, migration, and cultural change. Their modern Arabic language and predominantly Muslim faith are historically significant layers, not immutable markers of origin. Beneath them lie older strata: Canaanites, Philistines, Hebrews, Greeks, Romans, Arabs, Crusaders, Ottomans – peoples who arrived, mixed, converted, intermarried, and remained. Palestinian identity is grounded not in racial purity but in historical presence, social continuity, and sustained attachment to land.

The broader reality is that the peoples of the Levant are interconnected rather than discrete. Ancient Levantine ancestry flows through both modern Jewish and Palestinian populations. The region has always been a mosaic, shaped by movement rather than isolation, by overlap rather than exclusion. Attempts to categorically separate Jews and Palestinians – biologically, historically, or morally – are less grounded in evidence than in polemic. They simplify a shared past in service of present-day argument.

Understanding identity in this layered way clarifies a crucial point: claims of “first,” “pure,” or exclusive belonging are historically misleading. Both Jews and Palestinians are inheritors of the land in overlapping and entangled ways. If indigeneity is understood as sustained attachment to place, culture, and memory, then it applies to both. Each carries the land in story and ritual, in family memory and embodied history. Neither people’s connection is negated by the presence of the other.

The Levant has never been static. Jewish communities absorbed influences from Egypt, Babylon, Rome, and Europe while maintaining continuity with their Levantine origins. Palestinian communities likewise carry the genetic and cultural imprints of successive civilisations layered onto a continuous local presence. Both are products of continuity through multiplicity. Both are indigenous not because they are unchanged, but because they have endured.

Recognising this multiplicity undermines the temptation to treat indigeneity as an exclusive claim. Jewish historical connection does not erase Palestinian continuity; Palestinian rootedness does not negate Jewish ancestral ties. Their histories are not competing ledgers of legitimacy. They are overlapping inheritances inscribed into the same hills, valleys, and cities. History here does not operate as a zero-sum game.

The error arises when indigeneity is weaponised – when one people’s connection is elevated only by recasting the other as foreign, derivative, or invented. This logic echoes through debates over naming, settler-colonial framing, and historical legitimacy, where memory becomes proof, ancestry becomes argument, and recognition is treated as a finite resource. Yet the historical, archaeological, cultural, and genetic record consistently resists such neat separation.

Acknowledging multiplicity shifts the conversation away from moral absolutism toward historical understanding. Multiplicity clarifies the Levant’s moral geography. To be indigenous in the Levant is to belong to a palimpsest – to carry the land in memory, culture, and body while sharing it with others who do the same. Both Jews and Palestinians meet these criteria. Both are rooted. Both are inheritors. Both bear trauma and attachment, memory and aspiration.

Both possess a need to belong, to anchor identity in soil, to maintain continuity across generations. Both are entangled with history, trauma, and memory. Both assert presence and attachment without cancelling the other. And yet politics has rendered these dreams asymmetrical: one realised in statehood, the other deferred in exile. The Levant’s moral geography demands recognition of both impulses, even where political realities frustrate fulfilment.

The broader lesson is straightforward but demanding: indigeneity does not grant exclusivity; continuity does not require erasure; ancestry does not mandate conquest. In a land shaped by layered histories, any serious moral or political imagination must reckon with overlap, entanglement, and coexistence -not pretend that one lineage can cancel another. Recognising shared yet distinct claims is not a compromise of truth. It is, rather, fidelity to historical reality itself.

Aliyah and al-‘Awda: the twin mirrors of return

The parallel dreams of Aliyah and Al-‘Awda. illustrate this entanglement. These two words embrace two histories and two dreams, and also, haunting symmetry. Each carries the weight of exile and the promise of homecoming. Both animate national imagination. Both are rooted in soil, memory, and moral inheritance. And both illustrate how deeply intertwined Jewish and Palestinian connections to the land truly are.

They are mirror dreams, shaped by different histories but animated by the same human impulse: the need to belong, to root identity in soil, and to carry continuity across generations fractured by exile and loss. Each word gathers within it a history of displacement and a promise of return; each turns geography into memory, and memory into moral claim. Together they reveal not a clash of myths, but an entanglement of inheritances embedded in the same hills, valleys, and stones.

Aliyah – literally “ascent” – is the Jewish return to Ha Aretz, the Land, at once physical and spiritual. It is pilgrimage and homecoming, covenant and geography braided together. For centuries of diaspora, Jews prayed toward Jerusalem, invoked the landscapes of scripture, and rehearsed return through ritual, law, and liturgy. Even when absence was enforced, presence was maintained in memory. Aliyah is therefore not merely migration but fulfilment: the realisation of a promise sustained across time, carried forward through text, prayer, and collective imagination.

Al-‘Awda – the Palestinian “return” – is equally profound, though shaped by a different rupture. It arises not from distant exile alone but from lived displacement: from villages depopulated in 1948, from homes lost or made unreachable under occupation, from continuity violently interrupted rather than slowly deferred. It is at once literal and symbolic, a longing for restoration and a refusal of erasure. Mahmoud Darwish, recognised as Palestine’s national poet, gave this longing its most enduring language, transforming Palestine into a moral landscape of memory and loss, where homeland becomes metaphor without ceasing to be real. In his poetry, return is not nostalgia but ethical insistence: the land remembers those who remember it.

The symbols of al-‘Awda – most famously al-muftah, the key – encode this insistence. The key appears in art, in refugee camps, in protest iconography not as a fantasy of reversal but as a declaration of continuity: doors once opened, homes once lived in, identities anchored in place even when bodies are barred from return. Like Aliyah, al-‘Awda is transmitted intergenerationally, carried in stories, photographs, olive groves, and family names that refuse to dissolve into abstraction.

Seen together, these two traditions expose a shared pattern. The land is never merely territory. It is memory made material, identity rendered geographical. Aliyah seeks reconnection with an ancestral homeland from which Jews were historically exiled; Al-‘Awda seeks restoration within a land Palestinians never wholly left. One is framed as fulfilment, the other as reclamation – but both arise from the same grammar of belonging, continuity under duress, and moral inheritance. The symmetry is haunting, even when the outcomes are radically unequal.

Politics, however, has rendered these dreams asymmetrical. Aliyah culminated in statehood; al-‘Awda remains deferred, constrained by demography, sovereignty, and an international system that has institutionalized exile without resolving it. This disparity has encouraged a zero-sum reading in which one return is treated as legitimate history and the other as an insoluble problem. Yet such framing obscures the deeper truth: attachment to land is not exclusive. Memory does not cancel memory. Longing does not negate longing.

Understanding Aliyah and al-‘Awda side by side clarifies why claims of precedence -“first,” “original,” “native” – fail to capture the moral complexity of the Levant. Indigeneity here is not a single thread but a braid: sustained attachment expressed through ritual and law on one hand, through lived presence and inherited community on the other. Jewish and Palestinian connections to the land are not mutually annihilating; they are layered, overlapping, and historically entangled.

The Levant is not a ledger in which legitimacy must be won and lost. It is a palimpsest, bearing multiple inscriptions of memory, loss, and return. Aliyah and Al-‘Awda are not opposites but reflections—each giving form to the same human need to belong, to return, to anchor the self in soil and story. The tragedy lies not in the coexistence of these dreams, but in the political imagination that insists only one may be honoured.

To recognise both is not to resolve the conflict, nor to sentimentalise it. It is simply to acknowledge the moral geography of the place itself: a land that carries more than one inheritance, more than one claim, more than one dream—and demands a capacity to hold multiplicity, even where fulfilment remains contested.

Seen this way, Aliyah and al-‘Awda are not merely parallel dreams of return, but incompatible political grammars shaped by trauma, timing, and power. Each encodes a moral claim that feels existential to those who carry it, yet threatening to those on the other side. Jewish return, forged in diaspora and catastrophe, demanded permanence and sovereignty; Palestinian return, forged in dispossession and exile, demanded reversal and restoration. Both are rooted in continuity and memory, yet when translated into politics rather than poetry, each risks negating the other. The tragedy is not that these aspirations exist, but that history arranged them to collide – each seeking justice through a vision that leaves little room for the other’s survival.

[In In That Howling Infinite, see Visualizing the Palestinian Return – the art of Ismail Shammout]

Al Mufta مفتاح

Return, continuity, and multiplicity

The mirrored impulses of Aliyah and al-‘Awda reveal a deeper pattern in the Levant: land as inheritance, memory, and moral geography, not merely as territory. Jewish Aliyah—the ascent to Ha Aretz—is rooted in centuries of diaspora experience, ritual, and ancestral memory. Palestinian al-‘Awda—the dream of return—is grounded in lived experience, collective memory, and the trauma of displacement. Both articulate belonging, both assert continuity, and both affirm a claim to presence, yet neither is reducible to exclusive ownership.

Understanding these aspirations through the lens of indigeneity clarifies the Levant’s complexity. Indigenous identity is not defined solely by ancestry or race, but by sustained attachment to place, unique culture, language, and historical continuity. Jewish communities, even after centuries in diaspora, maintained a living connection to the land through prayer, law, and cultural memory; Palestinians, continuously inhabiting villages, towns, and cities, preserve attachment through lived experience, story, and inherited community. Both meet the criteria of indigenous presence, both are rooted in the same soil, and both inherit overlapping geographies.

Multiplicity is the key. Neither Aliyah nor al-‘Awda exists in isolation; both emerge from entangled histories, migrations, and interwoven ancestries. The Levant is not a canvas for singular claims, nor a ledger for moral points. It is a palimpsest, where dreams, memory, and continuity coexist—even when politics imposes a zero-sum frame. Recognising this multiplicity transforms how we see legitimacy: it is not a finite resource to be won or lost, but a shared inheritance to be acknowledged.

In this light, the “return” is as much about imagination and moral continuity as it is about geography. The Jewish ascent, the Palestinian return, the dreams held in exile or diaspora, all testify to the same human impulse: to belong, to anchor identity in soil, and to see history not merely as a past but as an inheritance shaping the present. Both peoples carry the land in body, memory, and story; both dreams illuminate the impossibility—and the necessity—of coexistence.

Ultimately, Aliyah and al-‘Awda demonstrate that historical continuity, cultural memory, and ancestral attachment are not zero-sum. The land can carry more than one claim, more than one people, more than one dream. What is required is a moral and political imagination capable of holding multiplicity, of recognising overlapping rights, and of acknowledging that inheritance is shared, entangled, and enduring.

Why sharing the land has proved so difficult

If there is a single, stubborn question running beneath all of this, it is not who belongs, but why coexistence has proved so elusive. Two peoples, both rooted, both carrying memory, both claiming continuity – yet locked into a conflict that seems to resist every appeal to shared humanity.

One part of the answer lies not in antiquity, but in modernity – in the habits of mind carried from Europe to the eastern Mediterranean. Ilan Pappé argues, persuasively, that early Jewish settlers in Palestine, particularly in the late Ottoman and Mandate periods, largely did not see the local Arab population as a political subject. They were not the object of hatred, exactly; they were something more corrosive – irrelevant. The project was inward-facing: to build, to revive, to normalise Jewish life after centuries of vulnerability and persecution. The locals did not so much obstruct the vision as fail to register within it.

This indifference was not uniquely Jewish. It was recognisably European. The mindset closely resembled that of settlers who arrived, with their own fears and hopes, on the shores of North America, Australia, or the Cape. They came not primarily to dominate, but to begin again – to escape religious persecution, economic stagnation, or political precarity. The land appeared underused, underdeveloped, waiting. The people already there were often perceived less as political actors than as features of the landscape – present, but not decisive.

One does not need much imagination to see how this felt from the other side. To be continuous, rooted, embedded in place—and yet rendered invisible by a project unfolding around you. To watch newcomers build institutions, towns, and legal frameworks that did not include you, did not consult you, and did not imagine you as co-heirs. Even absent overt malice, this was experienced as dispossession in slow motion.

What makes the Jewish–Palestinian case especially tragic is that the settlers themselves were not an imperial metropole exporting surplus population, but a people long excluded, often brutalised, and desperate for normality. Zionism was not merely a political ideology; it was a survival strategy. Yet survival pursued without recognition of those already present reproduces—unintentionally – the very hierarchies it seeks to escape. Moral urgency crowds out moral vision. One people’s existential fear eclipses another’s lived reality.

This is where the conflict begins to harden. Palestinians experienced Zionist settlement not as return, but as arrival; not as redemption, but as replacement. Jews experienced Palestinian resistance not as indigenous defence, but as rejection of their most basic claim to safety and self-determination. Each side misread the other through the lens of its own trauma. Each interpreted the other’s actions as negation.

Once this dynamic sets in, sharing the land becomes psychologically – and then politically – extraordinarily difficult. Fear replaces curiosity. Memory becomes weaponised. Every concession feels like erasure. What began as indifference curdles into mistrust, and mistrust into moral absolutism. The box canyon narrows: only one narrative can survive; only one future can be imagined.

And yet history rarely leaves asymmetry unreciprocated.

If early Zionist indifference helped harden Palestinian resistance, Palestinian political culture also evolved in ways that increasingly mirrored the exclusivist logic it opposed. Faced with dispossession, fragmentation, and repeated defeat, Palestinian identity cohered around loss—around al Nakba as organising principle, and al-‘Awda as moral horizon. Over time, this produced not only solidarity and resilience, but also a narrowing of political imagination. Jewish presence came to be read not as layered or historical, but as entirely alien; Jewish continuity was reframed as fabrication, invention, or fraud.

This was understandable as a defensive reflex – but it came at a cost. By denying Jewish indigeneity altogether, Palestinian leadership and its external advocates adopted the same zero-sum logic they rightly condemned. Recognition became conditional, legitimacy indivisible. What began as a struggle against erasure risked becoming a project of counter-erasure. The hierarchy of malice inverted itself but did not disappear.

At the same time, the familiar settler-colonial frame begins to strain under the weight of historical complication. The early Jewish settlers were indeed overwhelmingly European in origin, language, and political culture, arriving with mental furniture shaped by Europe: nationalism, socialism, agrarian revival, and the settler imagination. In that sense, they do fit the classic profile of settler colonists, and this provides much of the grist for contemporary anti-Zionist critique. But the Yishuv did not imagine—could not have imagined—the demographic rupture that followed 1948: the arrival of nearly a million Jews expelled or forced to flee from Arab countries and Iran.

These Mizrahi Jews were not European interlopers parachuted into the Middle East. They were, to all practical purposes, Arab Jews Arabic-speaking, culturally embedded in the region, shaped by its music, food, social codes, and outlook. Their displacement from Baghdad, Cairo, Damascus, Sana’a, Fez, and Tehran was not incidental to Israel’s formation; it became constitutive of it. The state that emerged was not simply a transplanted Europe, but an improvised, often uneasy fusion of diasporas – Ashkenazi, Sephardi, Mizrahi – many of them poor, marginalised, and themselves refugees. [In In That Howling Infinite, see The Mizrahi Factor

This complicates the moral geometry. Israel becomes not a single settler project with a clear metropole and periphery, but a crowded refuge absorbing multiple expulsions at once. After more than seventy years, this reality is immediately visible to anyone who lands at Ben Gurion: Israel is not, and has not been for a long time, a “white” country, whatever the slogans suggest. That this fact is so rarely acknowledged let alone integrated into popular discourse—reveals how rigid and inattentive many contemporary moral frameworks have become.

Thus, both peoples arrived – by different routes – at a similar impasse. Each came to see itself as the true refugee of history. Each feared that recognising the other’s depth of attachment would annul its own. Each retreated into a moral box canyon of absolute narratives.

What was lost, on both sides, was the possibility of shared inheritance – of seeing the land not as a prize to be awarded, but as a burden to be carried together. The tragedy is not that two peoples loved the same land. It is that they entered modern politics with incompatible expectations shaped by Europe’s long shadow, and neither fully saw the other in time. Once mutual visibility is lost at the beginning, history has a way of compounding the error.

Understanding this does not assign guilt in tidy proportions. It asks something more demanding: to recognise how good faith, deep attachment, and legitimate claims can still produce a conflict that feels unsolvable –

not because one side is uniquely wicked, but because both became trapped in stories that left no room for the other to remain.

Only by loosening those stories—by allowing attachment to coexist without cancellation—does the land begin to re-emerge not as a zero-sum possession, but as something closer to what all indigenous traditions, in different tongues, have always known it to be: not owned, but endured; not conquered, but shared.

Why the Two-State horizon has receded – perhaps for a generation

If the two-state solution once functioned as a shared horizon -distant, hazy, but orienting -it now lies behind a wall of wreckage. Not abandoned in theory, perhaps, but rendered inert by history’s latest accelerant. October 7 2023 and the Gaza war that followed did not create the impasse; they detonated it.

The occupation, long described as “temporary,” has hardened into a permanent condition—administrative, psychological, and moral. It is no longer experienced by most Israelis as an emergency requiring resolution, but as an ambient fact of life, managed like traffic or crime. For Palestinians, it is no longer experienced as a condition awaiting negotiation, but as an enclosure tightening year by year: land eaten away by settlements, movement throttled by permits and checkpoints, political agency hollowed out by collaborators, donors, and armed factions alike. This normalisation corrodes both sides simultaneously. The occupation deforms Israel’s moral language while dissolving Palestinian political coherence. Each adapts in ways that make disentanglement harder.

In the West Bank, the ongoing “range war” in the hills and fields – the quiet violence of settler depredations, land seizures, olive groves torched, mosques and churches vandalised – has become the grinding background noise of daily life. It is rarely decisive enough to provoke international rupture, but cumulative enough to destroy trust entirely. The IDF’s role as occupying power, security guarantor, and—too often—arbiter of civilian life entrenches a system in which force substitutes for politics. The more soldiers are deployed to police civilians, the more civilian resistance becomes criminalised, and the more violence is routinised on both sides.

Yet this is only half the picture, and you are careful not to avert your gaze from the other half.

Despite the Separation Wall, despite the intelligence dragnet, despite the overwhelming asymmetry of power, there are still thousands of attacks on Israeli civilians each year—stabbings, shootings, car rammings, rockets, lone-wolf assaults. They do not threaten Israel’s existence, but they do something more corrosive: they reaffirm, daily, the belief that withdrawal invites annihilation. For Israelis shaped by the Second Intifada—and now by October 7—the line between occupation and survival has collapsed. Every concession is read as exposure. Every Palestinian death is tragic; every Israeli death is existential.

As Warren Zevon sang,”the hurt gets worse and the heart gets harder”. That lyric captures something neither UN resolutions nor peace plans ever quite grasp: trauma compounds. It does not cancel out.

October 7 shattered whatever residual belief remained among Israelis that separation could be achieved without mortal risk. Gaza – already sealed off, already written off by many Israelis as a lost cause – became proof, in their minds, that withdrawal does not end conflict, it relocates it closer to home. The war that followed, with its vast civilian toll, obliterated any remaining Palestinian faith that Israel distinguishes meaningfully between combatant and captive population. Each side now possesses fresh, blood-warm evidence for its bleakest assumptions about the other.

In this climate, the two-state solution survives mostly as rhetoric – recited by diplomats, invoked by editorial boards, but no longer animated by constituencies willing to pay its price. The Israeli electorate has moved decisively toward management over resolution: control without citizenship, security without reconciliation. The Palestinians, fragmented between a corrupt, hollowed-out Authority in the West Bank and a nihilistic, theocratic militia in Gaza, lack both legitimacy and leverage. There is no credible partner on either side capable of delivering compromise without being destroyed by their own people.

And beneath all this lies the deeper fracture you keep returning to: mutual invisibility.

Most Israelis no longer encounter Palestinians as neighbours, co-workers, or fellow citizens-in-waiting. They encounter them as threats, filtered through screens or uniforms. Most Palestinians encounter Israelis almost exclusively as soldiers, settlers, or jailers. Each people experiences the other not in ordinary human contexts, but at the sharp edge of power. This is not a soil from which compromise grows.

The two-state solution depended, at minimum, on three conditions: a belief in eventual separation, a willingness to recognise the other’s legitimacy, and a shared sense that time was running out. All three have inverted. Separation now feels dangerous. Recognition feels like surrender. And time feels abundant—because the status quo, however ugly, appears survivable.

That is why the two-state outcome is not merely stalled but suspended by psychology as much as by geography. It may yet return -but not soon, and not until a generation shaped by checkpoints, rockets, funerals, and revenge has loosened its grip on the wheel.

Until then, Israel and Palestine remain, as Avi Shalit put it, locked in a grotesque embrace: one squeezing for control, the other for breath. Trapped by each other, and by histories that have taught them, again and again, that to relent is to perish.

The tragedy is not that solutions are unknown. It is that, for now, neither side can imagine surviving the journey to them.

That, more than borders or maps, is why the two-state horizon has receded—and why, in the wreckage of October 7 and Gaza, it may take a generation before it comes back into view.

The transformation of Palestinian nationalism from secular to Islamist

Palestinian nationalism, like much Arab nationalism, was not always framed in the language of religion. In the early twentieth century, movements across the Levant—anti-colonial, anti-Zionist, and Arabist—were largely secular, rooted in a combination of local civic identity, anti-imperial sentiment, and the vision of a shared Arab polity. Leaders envisioned the liberation of Palestine and the establishment of self-governing institutions through political mobilization, diplomacy, and, at times, armed struggle, rather than religious imperatives.

Over the decades, however, the ideological contours of Palestinian nationalism shifted markedly. The repeated failures of secular parties, the political fragmentation of the Palestinian leadership, the enduring dislocations of the diaspora, and the harsh realities of occupation contributed to a turn toward religion as both a mobilizing force and a framework for justice. By the late twentieth century, Islamist movements like Hamas and Islamic Jihad had emerged not simply as religious actors, but as ideologically coherent alternatives to secular nationalism. These groups foreground jihad, martyrdom, and the religious sanctity of the land in their rhetoric, framing the struggle for Palestine as a cosmic as well as temporal obligation.

The transformation is reinforced and symbolically anchored in sites of singular significance. The Haram al-Sharif—or Al Aqsa compound—has become more than a physical locus; it is an icon, a rallying point, and a metonym for the broader struggle. Events such as the naming of military campaigns “Al Aqsa Flood,” and the explicit articulation of eschatological promises, like the “Hamas Promise of the Hereafter,” signal the intertwining of politics and theology in contemporary mobilization. For many young Palestinians, religiosity is inseparable from identity and resistance, shaping curricula, media consumption, and communal norms, and providing moral justification and existential purpose to a struggle defined by occupation, dispossession, and chronic vulnerability.

This turn toward Islamist framing cannot be understood in isolation from the broader regional context. Iran’s “Axis of Resistance”—its network of ideological, financial, and military support extending to Hezbollah, Palestinian Islamic factions, and other actors—has reinforced the sectarian and geopolitical overlay on what was once largely a nationalist struggle. Palestinian nationalism, once secular and civic, is now entangled with a wider regional contest over ideology, faith, and influence.

The result is a politics that is profoundly resistant to compromise. Where once the possibility of pragmatic negotiation might have existed under secular leadership, religious imperatives, narratives of martyrdom, and the sanctity of sacred space have complicated the landscape. The intersection of youth religiosity, ideological indoctrination, regional sponsorship, and symbolic geography means that even limited concessions are difficult to imagine without appearing sacrilegious, existentially threatening, or politically fatal.

In sum, the ideological evolution of Palestinian nationalism—from secular, civic, and political mobilization toward religiously framed struggle—illuminates why contemporary conflict cannot be understood solely through the lens of territory or governance. It is simultaneously geopolitical, generational, and spiritual, embedded in the sacred geography of the land and in the cosmology of a people who have endured loss, occupation, and existential threat. Understanding this transformation is essential to comprehending why peace is so elusive, why the Two-State Solution is increasingly improbable, and why the wounds of October 7 and the Gaza War are likely to reverberate across generations. [In In That Howling Infinite see Lebensraum Redux – Hamas’ promise of the hereafter and Al Aqsa Flood and the Hamas holy war.

Israeli religiosity, nationalism, and the hardening of intransigence

Just as Palestinian nationalism has shifted from secular civic aspiration to an Islamist, jihad-inflected orientation, Israeli politics and identity have undergone a parallel, if distinct, transformation. The early Zionist project—rooted in secular socialism, pragmatic state-building, and European Jewish cultural memory—emphasized settlement, cultivation, and defense of a Jewish homeland, but largely avoided overt messianism or religious justification for territorial claims. For decades, labor Zionism and pragmatic governance dominated the state, seeking coexistence when possible and security when necessary.

Over time, however, particularly following the 1967 war and Israel’s acquisition of the West Bank, Gaza, and East Jerusalem, a potent strain of religious-nationalist ideology gained influence. Settler movements, many infused with messianic belief, framed the West Bank and other “biblical heartlands” not as disputed territory to be negotiated but as divinely mandated inheritance. Military victory became moral vindication; the conquest of hills, valleys, and historic cities was interpreted as the fulfilment of prophecy. For many young Israelis—particularly those raised in settler communities or religious schools—attachment to the land is inseparable from divine obligation, identity, and collective destiny.

The fusion of religiosity with nationalism has been reinforced by political consolidation. Governments led by right-wing parties, often aligned with settler constituencies and religious Zionist ideologues, have enacted policies that expand settlements, prioritize security over compromise, and embed ideological imperatives into law and practice. The “Greater Israel” project is not merely strategic; it is sacred, moral, and historical. Even military service, once largely secular, now socializes many Israelis—soldiers, conscripts, and officers alike—into a worldview in which defense, occupation, and settlement are intertwined with divine sanction.

This hardening of ideology has been mirrored culturally. Public rituals, school curricula, media, and religious observance reinforce narratives of historical continuity, existential threat, and moral righteousness. Palestinian identity is often perceived through a lens of threat, suspicion, or delegitimization—echoing the zero-sum dynamics that have hardened Palestinian views in response. Generationally, the result is a cohort of Israelis for whom compromise is morally fraught, politically risky, and psychologically difficult. [In In That Howling Infinite, see A Messiah is needed – so that he will not come]

The convergence is stark. On one side, Palestinian youth are inculcated with religiosity, martyrdom, and symbolic attachment to sacred sites; on the other, Israeli youth are shaped by historical consciousness, messianic settlement ideology, and the ethos of defense and divine inheritance. Both trajectories interact with persistent violence, security operations, and cycles of attack and reprisal to produce symmetrical intransigence: each side perceives the other not merely as a political opponent, but as a moral and existential threat.