“All wars come to an end and that’s where history restarts”

“History stretches out into the future as well as the past”

“All wars may end in negotiations, but not all negotiations end wars”

The indefatigable British journalist, author, and longtime Beirut resident Robert Fisk Robert Fisk died of a stroke in St Vincent’s Hospital, Dublin, on October 30, 2020. He was 75. Fearless and inquisitive, often iconoclastic and controversial, “Mister Robert,” as he was known from Algeria to Afghanistan, was one of the finest journalists of his generation—the greatest reporter on the modern Middle East. There is probably no better body of work for understanding the region. Respected and reviled in equal measure by left and right alike, Fisk spoke truth to power for more than half a century.

He was obsessive, he was angry, and – having read many of his books – I believe he suffered from undiagnosed PTSD throughout his career in the Middle East. His lifelong obsessions were the arrogance and misuse of power, the lies and impunity of the rulers: presidents and prime ministers, kings and emirs, dictators and theocrats, torturers and murderers. And always the countless innocents who endured and suffered, dying in their tens – and tens – of thousands on the altar of power and greed.

The Night of Power

His last book, The Night of Power: The Betrayal of the Middle East, published posthumously in 2023, takes up where his monumental The Great War for Civilisation (2005) ended—with the contrived U.S.-British-Australian invasion of Iraq. The Great War for Civilisation was a tombstone of a book, literally and figuratively, as was its predecessor Pity the Nation (1990), his definitive history of the Lebanese civil war.

The Night of Power is no less harrowing, covering the occupation of Iraq, the 2006 Israel–Lebanon war, the Arab Spring, the rise of Egypt’s new pharaoh Abdel Fattah al-Sisi, the lonely death of Mohammed Morsi, Israel’s occupation of the West Bank and seize of Gaza, and the Syrian civil war. It ranges widely – but its coherence lies in Fisk’s unrelenting theme: the cycle of war, the corruption of power, and the persistence of memory. To read it is to feel Fisk’s own cynicism, sadness and anger.

The title is deeply symbolic. In Islamic tradition, Laylat al-Qadr, the Night of Power, is the night the Qur’an was first revealed to the Prophet Muhammad: “The Night of Power is better than a thousand months … Peace it is, until the rising of the dawn” (Qur’an 97). It is a night of blessing beyond measure, greater than a lifetime of devotion. The title is bitterly ironic: the “night of power” he recounts is one of betrayal, cruelty, and endless war.

It is both a summation of his life’s work and a testament to his method. Over four decades, Fisk was a witness to almost every major conflict in the Middle East — Lebanon, Iran, Iraq, Palestine, Algeria, Afghanistan, Syria, Egypt — and the wars of the Yugoslav succession. His dispatches carried both forensic detail and moral outrage. This last work, published in the year of his death, is less a memoir than a vast chronicle of empire, war, betrayal, and resistance.

Fisk had long insisted that reporters must “be on the side of those who suffer.” He was no neutral stenographer of official sources. He distrusted governments – Western and Arab alike – and prized first hand testimony, walking the ruins, speaking to survivors, writing down the words of the powerless. The Night of Power continues in this vein, but with a sharpened sense of history. Fisk threads together centuries of conquest and resistance, showing how imperial arrogance, local despotism, and religious zealotry have conspired to devastate the region.

The last two paragraphs Robert Fisk wrote before his death, closing The Night of Power, cut like a blade through the pieties of Western journalism:

“Failure to distinguish between absolute evil, semi-evil, corruption, cynicism and hubris produced strange mirages. Regimes which we favoured always possessed ‘crack’ army divisions, ‘elite’ security units, and were sustained by fatherly and much revered ruling families. Regimes we wished to destroy were equipped with third-rate troops, mutineers, defectors, corrupt cops, and blinded by ruling families. Egypt with its political prisoners, its police torture and fake elections, was a tourist paradise. Syria with its political prisoners, police torture and fake elections, would like to be. Iran, with its political prisoners, police torture and fake elections was not — and did not wish to — be a tourist paradise.” (p. 533)

In the end, according to those closest to him, including his wife Nelofer Pazira-Fisk, an award-winning Afghan-Canadian author, journalist and filmmaker, who edited the book and wrote its final chapter, Fisk despaired. He feared that nothing he had written over four decades had made any difference – that things had, in fact, grown worse. As Kent says to the blinded King Lear, “All is cheerless, dark, and deadly”.

And yet the worst was arguably still to come: the chaotic retreat of America and its allies from Afghanistan and the Taliban’s reimposition of rule, including the literal silencing of women’s voices; Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and its murderous war of attrition that has now passed its thousandth day; Hamas’s atrocity of October 7, 2023, Israel’s biblical-scale revenge, and the utter destruction of Gaza; and the latest Israel–Lebanon war that saw the decapitation and emasculation of Hezbollah.

The Legacy of a Fearless Reporter

The Night of Power stands as a testament to Robert Fisk’s fearless journalism and his relentless moral compass. Across decades of war reporting, Fisk bore witness to suffering few dared to confront. He was unflinching in exposing the hypocrisies of Western powers, the brutality of dictators, and the costs of occupation, war, and empire. Yet he also captured the human dimension: the courage, endurance, and resilience of those who suffered, whether in Iraq, Gaza, Egypt, or Syria.

This final work synthesizes Fisk’s signature qualities: exhaustive research, direct engagement with the people whose lives were upended, and an ethical rigor that held both oppressors and complicit outsiders accountable. The Night of Power is not merely a chronicle of events; it is a meditation on power, betrayal, and history itself.

Fisk’s prose, vivid and often lyrical, reminds readers that journalism can be a form of witness — bearing truth against overwhelming odds. Even in despair, he recognized the persistence of human agency, the cycles of history, and the moral imperative to see, to name, and to remember. His death in 2020 marked the end of a career unparalleled in courage and conscience, but his work, particularly this last book, endures as both a warning and a guide for understanding the Middle East and the forces that shape our world.

In reading The Night of Power, one cannot avoid Fisk’s central lesson: history may restart at the end of every war, but the witness to injustice is what shapes the moral memory of humanity. The quotations at the head of this review, indeed, the final words of the book, weary yet resolute, are a fitting epitaph. Fisk saw the world as it was, not as we wished it to be: corrupt, cruel, but always turning, always restarting.

All wars come to an end and that’s where history restarts

Robert Fisk, The Night of Power

Postscript

The final chapter of The Night of Power was written by Fisk’s wife Nelofer Pazira-Fisk, She was based in Beirut for fifteen years working alongside her late husband and reported from Iraq, Afghanistan, Turkey, Egypt and Syria. The following podcast by American war correspondent Chris Hedges, with Fisk’s first wife Lara Marlowe is a worthy tribute .

See also, in In That Howling Infinite The calculus of carnage – the mathematics of Muslim on Muslim mortality

The following briefly summarizes the main themes of The Night of Power drawing largely upon his own words

Robert Fisk’s Catalogue of Carnage

Hear the cry in the tropic night, should be the cry of love but it’s a cry of fright

Some people never see the light till it shines through bullet holes

Bruce Cockburn, Tropic Moon

Iraq: Catastrophe Foretold

Fisk argued that Iraq’s occupation was fraudulent from the start, brutal in execution, and ferocious in its response to insurgency. The Americans tolerated the inhuman behaviour of their own soldiers, relied on mercenaries and “greedy adventurers,” and mixed Christian religious extremism with an absurd political goal of “remaking the Middle East.” It was “tangled up in a web of political naivety and Christian muscularity”.It was bound, he wrote, to end in catastrophe.

“We were pulling at the threads of the society with no sense of responsibility as occupiers just as we had no serious plans for state reconstruction. Washington never wanted Iraq’s land. Of course the countries resources were a different matter, but its tactics did fit neatly into the prairies of the old West. The tribes could be divided and occupiers would pay less in blood. as long as they chose to stay. One set of tribes were bought off with guns and firewater the other with guns and dollar bills. Serious resistance, however, would invoke “the flaming imperial anger” of all occupation armies.

The rhetoric echoed the 19th century missionary zeal of empire. Western fascination with the Biblical lands was used to justify conquest: as Lieutenant General Stanley Maude told the people of Baghdad in 1917, the Allies wished them to “prosper even as in the past when your ancestors gave to the world Literature, Science, and Art, and when Baghdad city was one of the wonders of the world” (p. 92).

The modern occupation, Fisk observed, was nothing but “the rape of Iraq”. Oil wealth was divided up in a scandal of corruption involving US contractors and Iraqi officials. “The costs were inevitably as dishonest as the lies that created the war … I knew corruption was the cancer of the Arab world but I did not conceive of how occupying Power supposedly delivering Iraqi their long sort freedom could into a mafia and at such breathtaking speed”.

Security became a malignant industry; by 2006 mercenaries accounted for half of Western forces, sucking money out of the country. The food system, 10,000 years old, was destroyed by Paul Bremer’s infamous Order 81, which forbade farmers from saving their own seed. Iraq became a “giant live laboratory for GMO wheat,” its people “the human guinea pigs of the experiment”.

And through it all, a campaign of suicide bombings – unprecedented in scale – turned Iraq into the crucible of modern terror. Editors never tried to count them. The figures, Fisk noted, were historically unparalleled.

The trial of Saddam Hussein

The US ambassador to Iraq once claimed she had been “unable to convince Saddam that we would carry through what we warned we would.” Fisk dismissed this as absurd. Saddam, he argued, was well aware of Western threats, but the framing of his trial was designed to obscure deeper truths.

If Saddam had been charged with the chemical massacre at Halabja, defence lawyers could have pointed out that every US administration from 1980 to 1992 was complicit in his crimes. Instead, he was tried for the judicial murder of 148 men from Dujail — heinous, but “trifling in comparison” (p. 92). The great crimes of the Baathist regime — the 1980 invasion of Iran, the suppression of Shia and Kurdish revolts in 1991 — were deemed unworthy of the court’s attention.

Pakistan: Fragile State, Useful Pawn

Fisk’s lens widened to Pakistan, where he recorded with scorn the ISI’s admission that the reality of the state was defined not by American might but by “corrupt and low-grade governance”. A US intelligence officer boasted: “You’re so cheap … we can buy you with a visa, with a visit to the US, even with a dinner.”

This, Fisk suggested, was not just Pakistan but almost every Arab or Muslim state in thrall to Washington: Egypt, Jordan, Syria, the Gulf states under their dictators and kings, even Turkey. He wrote that Osama Bin Laden’s choice to hide in Pakistan embodied a weird symmetry: the man who dreamed of a frontierless caliphate sought refuge in the very sort of corrupt, Western-backed dictatorship he despised.

Rendition: Complicity in Torture

The “war on terror” extended beyond borders. CIA, MI5 and MI6 operatives were deeply involved in rendition. Prisoners were knowingly dispatched to states where torture was inevitable, even fatal. Fisk insisted on repeating this uncomfortable truth: Western democracies had integrated torture into their security architecture.

Israel and Palestine: The Last Colonial War

Fisk was unsparing in his treatment of Israel’s expansion. He rejected any obfuscation: Israel seized the opportunity to consolidate its control with a land grab for the most prominent hilltops and the most fertile property in the West Bank for settlements constructed on land legally owned for generations by Arabs, destroying any chance the Palestinian Arabs could have a viable state let alone a secure one.”). These settlements, he wrote, “would become the focus of the world’s last colonial war.”

He surmised: “Will the Jews of what was Palestine annex the West Bank and turn its inhabitants into voteless guest workers and all of mandate Palestine into an apartheid state? There was a mantra all repeat that only other way to resolve Israeli rule in the West Bank would be a transfer of the Palestinians across the Jordan into the Hashemite kingdom on the other side of the river. In other words, expulsion”

The Wall

Fisk’s Fisk’s description of the Separation Wall is dramatic and unforgettable: an “immense fortress wall” which snakes “firstly around Jerusalem but then north and south of the city as far as 12 miles deep into Palestine territory, cutting and escarping its way over the landscape to embrace most of the Jewish colonies … It did deter suicide bombers, but it was also gobbled up more Arab land. In places it is 26 feet or twice the height of the Berlin wall. Ditches, barbed wire, patrol roads and reinforced concrete watchtowers completed this grim travesty of peace. But as the wall grew to 440 miles in length, journalists clung to the language of ‘normalcy’ a ‘barrier’ after all surely is just a pole across the road, at most a police checkpoint, while a ‘fence’ something we might find between gardens or neighbouring fields. So why would we be surprised when Italian Prime Minister Silvio Berlisconi, traveling through the massive obstruction outside Bethlehem in February 2010 said that he did not notice it. But visitors to Jerusalem are struck by the wall’s surpassing gray ugliness. Its immensity dwarfed the landscape of low hills and Palestinian villages and crudely humiliated beauty of the original Ottoman walls Churches mosques and synagogues .. Ultimately the wall was found to have put nearly 15% of West Bank land on the Israeli side and disrupted the lives of a third of the Palestine population. It would, the UN discovered, entrap 274,000 Palestinians in enclaves and cut off another 400,000 from their fields, jobs, schools and hospitals. The UN concluded that many would “choose to move out.” Was that the true purpose?“.

Leftwing Israeli journalist Amira Haas, who lives in the West Bank, takes Fisk on a tour of the wall: “Towering 26 feet above us, stern, monstrous in its determination, coiling and snaking between the apartment blocks and skulking in wadis and turning back on itself until you have two walls, one after the other. You shake your head a moment – when suddenly through some miscalculation surely – there is no wall at all but a shopping street or a bare hillside of scrub and rock. And then the splash of red, sloping rooves and pools and trees of the colonies and yes, more walks and barbed wire fences and yet bigger walls. And then, once more the beast itself, guardian of Israel’s colonies: the Wall”.

See also, in In That Howling Infinite, Blood and Brick … a world of walls

Gaza: Junkyard of History

Although Oslo’s creators fantasied that it would become part of the Palestinian state, Gaza’s destiny was isolation. It has been a junkyard of history variously ruled by Christians and Muslims, ruined and rebuilt under the Ottomans, and fought for by the British and Turks in the First World War, and now reduced to a prison state.,

Egypt: A Revolution Betrayed

Mohammed Morsi embodied both hope and tragedy. “An intelligent, honourable, obtuse, arrogant and naïve man”. No visionary, he was “was shambolic, inspiring, occasionally brutal and very arrogant”. He set off down the road to Egyptian democracy with no constitution no parliament and no right to command his own countries army …set off down the road to democracy “with no constitution, no parliament and no right to command his own country’s army”. And when the end came, as come it must, he could not smell trouble; he did not see what was coming.

In a coup that was not a coup, which former British prime minister Tony Blair called “an awesome manifestation of power”, “the democratically elected president was suspended, the constitution annulled, tekevion stations closed, the usual suspects arrested … Yet President Obama could not bring himself to admit this. He asked the Egyptian military “to return full authority back to a democratically elected civilian government… Through an inclusive and transparent process” without explaining which particular elected civil civilian government he had in mind”.

This was just the beginning. In the six years that followed, Egypt’s executioners and jailers were kept busy. “They hung 179 men, many of them tortured before confessing to murder, bomb attacks or other acts of terrorism”. It was claimed that Al Sisi had returned the country to a Mubarak style dictatorship in the seven years of his own war against the brotherhood between 1990 and 1997. Mubarak’s hangman had executed only 68 Islamists and locked up 15,000. By 2019 Al Sisi had 60,000 political prisoners

To Fisk, this was a sign of fear as much as it was evidence of determination to stamp out terror. Al Sisi had three separate conflict on his hands: his suppression of the brotherhood on the ground that they were themselves violent terrorists, the campaign by Islam extreme groups against Egypt’s minority Christian cops, and most frightening of all the very real al Qaeda and ISIS war against Al Sisi’s own regime. “The prisons of the Middle East, Fisk concluded, were “universities for future jihadi”.

See also, in In That Howling Infinite Sawt al Hurriya – Egypt’s slow-burning fuse and Sawt al Hurriya – remembering the Arab Spring

Silencing the women of the revolution

The misogyny if the counterrevolution was stark. Fisk wrote: “… if the senior officers wished to prune the branches of the revolution the participation of women was something that could not be tolerated. Why did there suddenly occur without apparent reason a spate of sexual attacks by soldiers that were clearly intended to frighten young women off the street, revealing a side to the Egyptian military that none of us had recognised. The misogynistic and shocking display of brutality towards women that could not have been the work of a few indisciplined units”. With sexual assaults on women protesters, virginity tests and public humiliation, “heroes of the 1973 war had become molesters”.

The lonesome death of Muhammad Morsi

Morsi would struggle on for years before a series of mass trials would entrap him and his brotherhood colleagues and quite literally exhaust him to death. Morsi’s slow death in solitary confinement was, Fisk insisted, “utterly predictable, truly outrageous and arguably a case of murder”. He was denied treatment, denied family visits, denied a funeral. “To die in a dictator’s prison, or at the hands of a dictator’s security services”, Fisk wrote, “is to be murdered.”

It did not matter, he continued “if it was the solitary confinement, the lack of medical treatment or the isolation, or if Morsi had been broken by the lack of human contact for those whom he loved. “The evidence suggested that Morsi’s death must’ve been much sought after by his jailers, his judges, and the one man in Egypt who could not be contradicted. You don’t have to be tortured with electricity to be murdered”.

Fisk’s description of Morsi’s death is a sad one. “Symbolism becomes all”, he wrote. “The first and last elected president of a country dies in front of his own judges and is denied even a public funeral. The 67-year-old diabetic was speaking to the judges, on trial this time for espionage, when he fainted to the floor. Imagine the response of the judges when he collapsed. To be prepared to sentence a man to the gallows and to witness him meeting his maker earlier than planned must’ve provoked a unique concentration of judicial minds. could they have been surprised groups had complained of Morsi’s treatment for the world media and the world had largely ignored the denunciations. What might have been surprising to his judges was that he managed to talk for five minutes before he departed the jurisdiction forever?”

See also, in In That Howling Infinite, Nowhere Man – the lonesome death of Mohamed Morsi

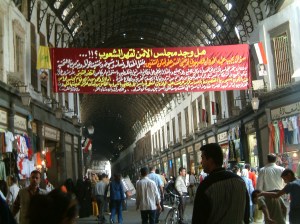

Russia in the Syrian Cockpit

Regarding Russia’s critical intervention in the Syrian civil war, Fisk wrote:

“We Westerners have a habit of always looking at the Middle East through our own pious cartography, but tip the map 90° and you appreciate how close Syria is to Russia and its Chechen Muslim irredentists. No wonder Moscow watched the rebellion in Syria with the gravest of concern. Quoting Napoleon, who said “if everyone wants to understand the behaviour of a country, one has to look at a map”, my Israeli friend (the late) Uri Avnery wrote that “geography is more important than ideology, however fanatical. Ideology changed with time”.

The Soviet Union, he continued was most ideological country in the 20th century. “It abhorred it predecessor, Tsarist Russia. It would have abhorred its successor, Putin‘s Russia. But Lo and behold – the Tsars, Stalin and Putin conduct more or less the same foreign policy. I wrote that Russia is back in the Middle East. Iran is securing its political semicircle of Tehran, Baghdad Damascus, and Beirut. And if the Arabs – or the Americans – want to involve themselves, they can chat to Putin”.

Author’s note

Laylatu al Qadri

لَْيلَُةاْلَقْدِر َخْيٌر ِّمْنأَْل ِف َشْھٍر. َسَلاٌم ِھَي َحَّتى َمْطلَِعاْلَفْجِر

Laylatu alqadri khayrun min alfi shahriin.Salamun hiya hatta matla’i alfajrii

The night of power is better than one thousand months.

(That night is) Peace until the rising of the dawn.

Al Qur’an al Karīm, Surat Al Qadr 97

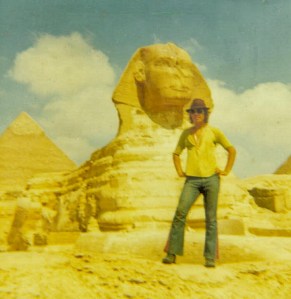

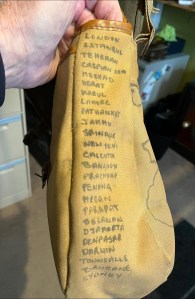

I first learned about the Quran and The Night of Power in Cairo when I was staying at the home of Haji Abd al Sami al Mahrous a devout Muslim doctor who had cared for me when I had fallen ill. There was a particular beauty and magic about the idea of a night that surpassed all other nights in sacredness. The fascination stayed with me, and when I returned to London and was learning Arabic and studying Middle East politic at SOAS, it inspired a song.

Shape without form, a voice without sound,

He moves in an unseen way;

A night of power, eternal hour,

Peace until the break of day;

The doubter’s dart, the traveller’s chart,

An arrow piercing even to the coldest heart,

A hand surpassing every earthly art,

And shows everyone his own way

Paul Hemphill, Embryo

When Freedom Comes, She Crawls on Broken Glass

In an earlier post in In That Howling Infinite, I wrote:

My song When Freedom Comes is a tribute to Robert Fisk (1946-2020), indomitable, veteran British journalist and longtime resident of Beirut, who could say without exaggeration “I walk among the conquered, I walk among the dead” in “the battlegrounds and graveyards” of “long forgotten armies and long forgotten wars”. It’s all there, in his grim tombstone of a book, The Great War for Civilization (a book I would highly recommend to anyone wanting to know more about the history of the Middle East in the twentieth century – but it takes stamina – at near in 1,300 pages – and a strong stomach – its stories are harrowing).

The theme, alas, is timeless, and the lyrics, applicable to any of what Rudyard called the “savage wars of peace” being waged all across our planet, yesterday, today and tomorrow – and indeed any life-or-death battle in the name of the illusive phantom of liberty and against those intent on either denying it to us or depriving us of it. “When freedom runs through dogs and guns, and broken glass” could describe Paris and Chicago in 1968 or Kristallnacht in 1938. If it is about any struggle in particular, it is about the Palestinians and their endless, a fruitless yearning for their lost land. Ironically, should this ever be realized, freedom is probably the last thing they will enjoy. They like others before them will be helpless in the face of vested interest, corruption, and brute force, at the mercy of the ‘powers that be’ and the dead hand of history.

The mercenaries and the robber bands, the warlords and the big men, az zu’ama’, are the ones who successfully “storm the palace, seize the crown”. To the victors go the spoils – the people are but pawns in their game.

In 2005, on the occasion of the publication of his book, Fisk addressed a packed auditorium in Sydney’s Macquarie University. Answering a question from the audience regarding the prospects for democracy in the Middle East, he replied:

“Freedom must crawl over broken glass”

When Freedom Comes, She Crawls on Broken Glass

There goes the freedom fighter,

There blows the dragon’s breath.

There stands the sole survivor;

The time-worn shibboleth.

The zealots’ creed, the bold shahid,

Give me my daily bread

I walk amongst the conquered

I walk amongst the dead

Paul Hemphill, When Freedom Comes

I reference this melancholy state of affairs in man of my songs:

High stand the stars and moon,

And meanwhile, down below,

Towers fall and tyrants fade

Like footprints in the snow.

The bane of bad geography,

The burden of topography.

The lines where they’re not meant to be

Are letters carved in stone.

They’re hollowed of all empathy,

And petrified through history,

A medieval atrophy

Defends a feeble throne.

So order goes, and chaos flows

Across the borderlines,

For nature hates a vacuum,

And in these shifting tides,

Bombs and babies, girls and guns,

Dollars, drugs, and more besides,

Wash like waves on strangers’ shores,

Damnation takes no sides.

Paul Hemphill, E Lucevan Le Stelle

“VISIT OF H.R.H. PRINCESS MARY AND THE EARL OF HARWOOD. MARCH 1934. PRINCESS MARY, THE EARL OF HARWOOD, AND THE GRAND MUFTI, ETC. AT THE MOSQUE EL-AKSA [I.E., AL-AQSA IN JERUSALEM].” LIBRARY OF CONGRESS, LC-M33- 4221.

“VISIT OF H.R.H. PRINCESS MARY AND THE EARL OF HARWOOD. MARCH 1934. PRINCESS MARY, THE EARL OF HARWOOD, AND THE GRAND MUFTI, ETC. AT THE MOSQUE EL-AKSA [I.E., AL-AQSA IN JERUSALEM].” LIBRARY OF CONGRESS, LC-M33- 4221.