How’s your ebb tide?

Do you sign on the dotted lion?

Is your tea nature Orpheus Rocker?

Who is Charlie Charm Puck in ‘Waltzing Matilda’

Back in London in the early seventies, when Earl’s Court in Kensington was such a mecca for itinerant Australians that it was known in London and in Australia as Kangaroo Valley, I was acquainted with many expatriate and transient Aussies. Indeed, I married one I’d met at the School of Oriental and African Studies where we were both studying.

Breaking free of the cultural confines of their conservative country, many young Aussies overcame historian Geoffrey Blainey called “the tyranny of distance” by flying across it or joining the famous Hippie Trail from Southeast Asia to what many still referred to as “The Old Country”. Some became household names, including actor Barry Humphries, writer Clive James, art critic Robert Hughes, journalists John Pilger, lawyer Geoffrey Robertson, fashion designer Jenny Kee and sociologist Germaine Greer, and bands like The Easy Beats and The Bee Gees, who were actually Poms returning home, and the Seekers. By far the most controversial were the editors of Oz Magazine, Richard Neville, Richard Walsh and Martin Sharpe, the defendants in the infamous Oz Trial of 1970, at the time, the longest obscenity trial in British legal history, and the first time that an obscenity charge was combined with the charge of conspiring to corrupt public morals. See The Australians who set 60s Britain swinging

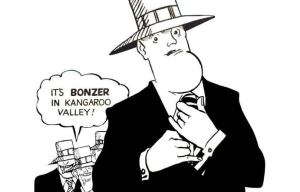

Most, however, were just ordinary folk, and they were so ubiquitous in London that they were often the butt of jokes (mostly good natured) and comedies, as personified in the cringeworthy uber-Coker Barry McKenzie which featured in Nicholas Garland’s comic strip in the satirical magazine Private Eye and Bruce Beresford’s dubious directorial debut, The Adventures of Barry McKenzie.

I was fascinated and highly amused by the Aussie’s accents and their many hilarious colloquialisms, including “I’m as dry as a dingo’s conger” and “flat out as a lizard drinking”. To assist my communication with these antipodean strangers, I purchased a little lexicon assembled by Professor Afferbeck Lauder of the University of Sinny. I was assured that this was exactly how Strine was spoke by dinkum Strayans.

When I emigrated DownUnder a few years later, I found that very few natives spoke proper Strine – though there was The Paul Hogan Show – that the Australian accent was perpetually evolving due to the country’s exposure to outside cultural influences – especially American and British – and its increasing multiculturalism.

Rereading Let Stalk Strine recently, I found was a little like opening a time capsule or deciphering a text of Chaucerian English, though vagrant traces of the old vernacular linger still in such “Australianisms” as nukelar, envimint, gomint, and, of course, Straya. But even the use of words such as these is not widespread, and usually confined to interviews with National Party politicians and Pauline Hanson.

The book is still available, and although air fridge Strines and new Strines no longer speak the lingo, it is picture of the strine wire flife half a century ago.

Here are some of my personal favourites. They’re still pretty grouse after all these years.

There’s “baked necks” and “egg nishner”, “garbled mince” and “nairm semmitch”, the public speaking opener “laze and gem…”, and the nursery rhyme Chair Congeal. There’s idioms like “fitwer smeeide” and “fiwers youide”, translated as “if I were you, I would” and “if I were you, I’d…” as in “fitwer smeeide leave him. He saw-way sonn the grog” and “fiwers youide leave him anode goan livener unit”. And there’s the prefix didjerie as in “didgerie dabout it in the piper” and “ didgerie lee meenit or were you kidding”, and, of course, “he plays the didgerie do real good”.

My personal favourite, relevant, apt even, to this day is “Aorta”.

To quote the author, it is “the personification of the benevolently paternal welfare state to which all Strines – being fiercely independent and individualistic- appeal for help and comfort in moments of frustration and anguish. The following are typical examples of such appeals. They reveal the innate reasonableness and sense of justice which all Strines possess to such a marked degree: “Aorta build another arber bridge. An aorta stop half these cars from cummer ninner the city – so a fella can get twerk on time”. “Aorta have more buses. An aorta mikey smaller so they don’t take up half the road. An aorta put more seats in ‘em so you do a tester stand all the time. An aorta put more room in ‘em. You can tardily move in ‘em air so cradled. Aorta do summing about it.”

For more on Australia in In That Howling Infinite, see Down Under

Struth Cobber