A king sate on the rocky brow

Which looks o’er sea-born Salamis;

And ships, by thousands, lay below,

And men in nations—all were his!

He counted them at break of day –

And when the sun set, where were they?

Lord Byron, Don Juan

Christopher Allen, The Australian’s art critic, writes of how Greece’s antiquity presses in on the present. It is a lightweight piece, surveying as it does three millennia of history, from the days of the Greeks, Alexander, the Great and the Romans to those of the Ottomans and their successor states – but it is elucidating nonetheless.

It is a brief reminder of the veracity of the phrase “history is always with us”, and of how the past continues to shape the present through its influence on culture, human nature, and ongoing events – a constant guide, providing both cautionary tales and inspiration for the future, as we carry our history with us in our identities, cultures, societies and recurring patterns of behaviour. As author and activist James Baldwin is attributed to have said, “History is not the past. It is the present. We carry our history with us. We are our history”.

Greece has always lived a double life. To the casual visitor, it is a sun-splashed idyll of sea and sky, but its history tells a darker story – a long, hard ledger of heroes and horrors, and the stubborn will to survive wedged between warring empires. The last two and a half millennia have been less a tranquil Mediterranean tableau than a parade of conquerors, liberators, and the occasional poet-adventurer.

Over time, Greece has drawn to its shores soldiers and adventurers, poets and dreamers – and naive youths like myself. I hitch-hiked down from what was then Yugoslav in the summer of 1970, a young man with a second-hand rucksack and followed the looping Adriatic highway from Thessaloniki and Athens. I knew enough history to feel the charge of passing near Thermopylae, where Spartans once made their famous last stand against the might of Xerxes. But I wasn’t to learn until over half a century later that an army of ANZACs battled overwhelming odds just a valley away.

The past, in Greece, as in the Middle East, always stands just offstage, awaiting its cue and refusing to stay politely within its own century. It is not merely one of the world’s most benevolent postcards; it is a crossroads of empires, a battleground of ambitions, a cavalcade of famous names and places, where East and West have met, mingled, clashed, and sometimes embraced in the long swirl of history, where the mythic and the modern travel together.

One particular reference also reminds me of how history sends out roots, twigs and branches throughout the settled and hence recorded world.

Tempe, on Sydney’s Cooks River, wears its classical inheritance more openly than most Sydney suburbs. When Alexander Brodie Spark built Tempe House in the 1830s, he christened the estate after the Vale of Tempe in northern Greece – a narrow, ten-kilometre gorge carved by the Pineiós River as it threads between Olympus and Ossa. The poets imagined Poseidon’s trident had cleft the mountains to make it; Apollo and the Muses strolled beneath its laurels; sacred branches were cut there for Delphi. Spark, standing between his own modest “Mount Olympus” and the river, saw a faint echo of the Greek idyll and gave the place its name.

But the Vale of Tempe was never entirely pastoral. Armies have squeezed through that narrow defile for millennia. The Persians marched through it on their way south – Tempe lies just north of the iconic pass of Thermopylae, part of the same chain of passes that determined so much of Greek military history. And in the twentieth century it would again become a stage for outsiders in uniform.

In April 1941 Australian and New Zealand troops, together with British units, were thrown into Greece as Lustre Force – outnumbered, outgunned, and facing a German army with air superiority and modern communications. One of the hardest-fought delaying actions took place – inevitably, given the geography – at Tempe Gorge on 18 April (the featured image of this post, from the collection of the Australian War Museum). The Australian brigade was commanded by Brigadier A.S. Allen, who had formed the first battalion of the new AIF. His “Anzac Force” (apparently the last operational use of that designation) held the gorge long enough to impede the German advance and allow wider Allied withdrawals. The serene valley Spark had sentimentalised became, for a few violent hours, an Anzac bottleneck: those same narrow walls that once sheltered shrines now channelling rifle fire and Stuka attacks. Many of those men would soon find themselves on Crete, resisting the first large-scale parachute assault in military history.

And then – because Australia never resists a touch of Mediterranean whimsy—the Hellenic (and Hellenistic) echoes continue in our own neighbourhood on the Midnorth Coast. Halfway along the road from Bellingen to Coffs Harbour lies the township of Toormina, home to our closest shopping centre and to the Toormi pub. Its name began its life on the slopes of Mount Tauro in Sicily, in the ancient town of Taormina, the site of a famous amphitheater. In the 1980s local Italian residents of who were clients of developer Patrick Hargraves (the late father of a good friend of ours) suggested the name “Taormina” for the new subdivision. He liked the idea but clipped the opening “a” to make it more easily pronounceable- and Toormina entered the Gregory’s and thelocal vernacular.

So in our small corner of New South Wales, Greek myth, Persian marches, Anzac rearguards, and Sicilian nostalgia all whisper from the signposts. Tempe and Toormina: unlikely twins, proof that even the quietest suburb can carry the long shadows of the ancient world.

See also in In That Howling Infinite, Ottoman Redux – an alternative history and The fall of the Ottoman Empire and the birth of Türkiye

Uncovering a forgotten Anzac story in Greece’s bloody history

From ancient battles to World War II, a visit to Athens’ War Museum exposes the dramatic military history that shaped modern Greece. Christopher Allen’s deeply personal connection unravelled in the process.

James Stuart, View of the Erechtheion, Athens, October 1787. Royal Academy of Arts, London. Photographer. Prudence Cuming Associates Limited.

A little over 200 years ago, the Greeks began their war of independence from the Ottoman Empire, which had conquered most of the Byzantine world in the 15th century; the renaissance in Western Europe thus coincided with the beginning of a new dark age for the Greeks under Turkish oppression. Some islands held out for longer: Rhodes, home of the Knights of St John, was taken in 1522, forcing them to withdraw to Malta; Cyprus, ruled by the French Lusignan dynasty from the time of the Crusades and then by Venice, was brutally conquered in 1571, and Crete, held by Venice since 1205, finally fell after a generation-long siege in 1669.

The Ottoman Empire reached the apogee of its power in the early 18th century, but then began a slow decline, one of whose incidental effects was to make the Greek world more accessible to Western travellers: James Stuart and Nicholas Revett spent time in Athens from 1751 and published their Antiquities of Athens in several volumes in 1762. By the early 19th century, Greece had become part of the itinerary of the Grand Tour; by 1816, the Parthenon Frieze was in the British Museum and profoundly transformed modern understanding of Ancient Greek art.

Meanwhile the Greek War of Independence began with revolts in the Peloponnese in 1821 and a Declaration of Independence in 1822, eliciting a savage response from the Turks and sympathy from intellectuals and the educated public in Western European countries. The slaughter of the population of the island of Chios in 1822 led Eugène Delacroix to paint his famous Massacre at Chios, exhibited in the Salon of 1824 and purchased in the same year for the national collection; it is today in the Louvre. In 1823, the most famous poet of his day, Lord Byron, who had already demonstrated his sympathy for Armenian culture and independence from the Ottomans, went to Greece to help in the fight, both personally and financially.

This 1813 portrait by Phillips depicts Lord Byron in traditional Albanian attire. Alamy

Byron’s death in 1824 at Missolonghi only attracted more attention and sympathy to the cause of Greek freedom, and the great powers – Britain, France and Russia – warned the Turks about further repression, even though they were also committed, for different reasons, to maintaining the integrity of the crumbling Ottoman Empire. In 1827, at the Battle of Navarino, an international fleet led by the British and commanded by Sir Edward Codrington destroyed the Turkish and Egyptian navies. After further interventions on land by Russian and French forces, the Ottoman Empire was compelled, by the Treaty of Constantinople in 1832, to accept the independence of mainland Greece, although initially only as far north as the so-called Arta-Volos Line. The north, including Thessaly, Macedonia and Thrace, remained in Ottoman hands and Mustafa Kemal Ataturk was born in the former Byzantine city of Salonika in 1881.

Instability in the Balkan provinces of the Ottoman Empire in the 1870s gave the new Greek nation the opportunity to annex the central region of Thessaly in 1881 (while Britain incidentally acquired Cyprus in 1878). Further important gains were made during the two Balkan Wars (1912-13): much of Epirus in the northwest as well as Salonika and most of southern Macedonia, most of the Aegean Islands and Crete; the British had already ceded the Ionian Islands in 1863 and the Italians would relinquish the Dodecanese after World War II in 1947. Meanwhile, in the aftermath of World War I, Greece had briefly seized eastern Thrace and territories in Anatolia, soon to be retaken by the Turks with immense loss of life in the Great Fire of Smyrna in 1922.

Model of Byzantine warship from the War Museum

This is of course a very much simplified version of the extraordinarily complicated story of Balkan politics from the mid-19th century, which forms such an important part of the lead-up to World War I. All of these events were accompanied not only by terrible military casualties on all sides, but by massive disruption to the population of lands where people of different ethnicities and faiths had lived side-by-side for centuries as part of a multiethnic empire, including war crimes and atrocities against civilians and non-combatants. And Greeks who had previously enjoyed political and economic prominence throughout the Ottoman world, including the Phanariots of Constantinople, were first stripped of their privileges, then persecuted and finally expelled in the tragic population exchange of 1923.

All of these events and many more are covered in the exhibits at the Athens War Museum, which I had never visited until a few weeks ago, but which gives a vivid idea of the almost continuous warfare that has been carried on over the past couple of centuries in a land most tourists imagine as a paradise of sea, sun and waterside taverns. The events of the war of liberation, especially as we pass through so many bicentenaries in the current decade, are naturally well represented: there is, for example, a new and interactive display devoted to the sea battle of Navarino and events surrounding this decisive moment in the war.

There are portraits of the many famous leaders of the independence movement in their picturesque costumes, as well as dramatic reimaginings of heroic battles, and of course weapons and equipment of the time. The resonance of the Greek struggle in Western Europe is recalled in a copy of Delacroix’s Massacre at Chios, as well as a version of Thomas Phillips’s portrait of Lord Byron in exotic Albanian costume (1813), of which the original hangs in the British embassy at Athens; another replica by the artist himself, but only of the head and shoulders, is in the National Portrait Gallery in London.

But there is much more about the history of Greece in Antiquity, and the chronological arrangement of the displays makes this an effective way to follow the sequence of events, especially the main episodes of the Persian Wars – with the great battles of Marathon in 490BC and Salamis in 480 – as well as the subsequent conflict between Athens and her quasi-subject states on one side and Sparta and her Peloponnesian allies on the other, known as the Peloponnesian War.

This disastrous war (431-404 BC) was followed in the second half of the fourth century by the rise of Philip of Macedon to hegemony, for the first time, over almost all of mainland Greece. After his assassination in 336, his young son, who became Alexander the Great, embarked on a spectacular campaign that led to the conquest of the whole of the vast Persian empire, from Egypt to what are now Afghanistan and Pakistan. Alexander’s conquests led to the extension of Greek language and civilisation deep into Asia, creating the international culture of the Hellenistic period, characterised among other things by a rich and complex exchange of ideas and forms between East and West.

He left an indelible impression on all the lands he conquered and is, for example, the first historical figure in the Persian national epic, the Shahname. By the time of Ferdowsi, who composed this masterpiece a millennium ago, the Persians had forgotten about the Achaemenid dynasty that first created the Persian empire in the sixth century BC; even the great site of Persepolis was and still is called Takht-e Jamshid, the throne of Jamshid, one of the mythical rulers from the great epic.

Each of Alexander’s battles – he is one of the handful of great generals never to have been defeated – is illustrated in clear diagrams, but they are also recalled in later images, in this case particularly in a series of 17th-century engravings whose story is probably unknown to almost all visitors to the museum. These are reproductions of gigantic paintings made as cartoons for tapestries commissioned by the young Louis XIV in the 1660s from Charles Le Brun, who was to become his court painter and who was later responsible for the decorations at Versailles, including the Hall of Mirrors. The series illustrates the valour but also the magnanimity of Alexander, as is clear from the moralising inscriptions attached in the engraved versions. For a long time, the huge canvases were not displayed at the Louvre, but for the last few decades have had their own room upstairs in the Sully wing.

Following the chronological sequence from antiquity we eventually get back to the war of independence and its sequels already mentioned above; but the story continues, after what the Greeks call the Asia Minor Catastrophe of the early 1920s, with a new calamity two decades later. For Mussolini invaded Greece in October 1940 expecting, like Putin in Ukraine, to achieve an easy victory and utterly underestimating the strength and resolve of the Greek army. By the following spring, it was clear that he was getting nowhere, and Hitler decided to come to his rescue by invading Greece in April 1941.

A. Bormans, engraving after Charles Le Brun Alexander and King Porus

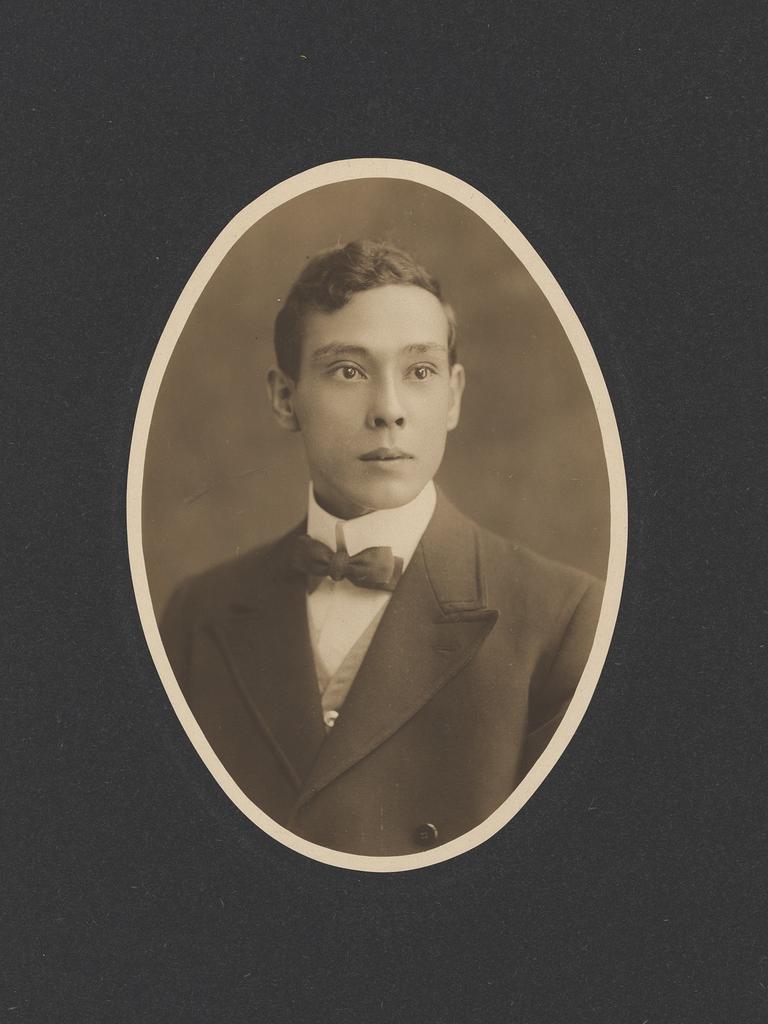

An Allied army, mostly consisting of Australian and New Zealand troops as well as some British units, was hastily put together and sent from Egypt to Greece as Lustre Force. It was heavily outnumbered by the Germans, who were also massively better equipped and had the benefit of air cover and wireless radio communication. Nonetheless, the Allied army put up a determined resistance in a series of battles including one notable action on April 18, 1941 at Tempe Gorge commanded by my grandfather, then Brigadier AS Allen, who had formed the first battalion of the new AIF and taken our first troops to World War II. The brigade he commanded at Tempe was known as “Anzac Force”, apparently the last use of the term, after the designation Anzac Corps for the whole Australian and NZ component of Lustre Force.

After the evacuation of mainland Greece, my grandfather was sent to fight the Vichy French in Syria, but many of our troops were taken to Crete, where in May 1941 they were faced with the first and only large-scale parachute assault in military history, in which the Germans suffered appalling casualties but ultimately prevailed. Next year will be the 85th anniversary of these dramatic events in Greece and Crete, and among other things will be commemorated by an exhibition of Australian and NZ artists whom I accompanied on a two-week tour of these battlefields in the second half of October.

It was a moving experience to visit what are today the peaceful sites of such desperate battles almost three generations ago, aware at the same time of the long history of warfare in the same lands: the Persians marched through Tempe, which is just north of Thermopylae; Caesar defeated Pompey at Pharsalus (now Farasala), which you pass on the train from Athens to Salonika (now Thessaloniki), and; Cassius and Brutus died at Philippi in Macedonia, defeated by the Caesarian forces of Octavian and Mark Antony.

Christopher Allen is the national art critic for Culture and has been writing in The Australian since 2008. He is an art historian and educator, teaching classical Greek and Latin. He has written an edited several books including Art in Australia and believes that the history of art in this country is often underestimated.