A man said to the universe:

“Sir, I exist!”

“However,” replied the universe,

“The fact has not created in me

A sense of obligation.”

American poet and author Stephen Crane, 1899

Statistics are sometimes used to express the scale of the destruction in Sudan. About 14 million people have been displaced by years of fighting, more than in Ukraine and Gaza combined. Some 4 million of them have fled across borders, many to arid, impoverished places—Chad, Ethiopia, South Sudan—where there are few resources to support them. At least 150,000 people have died in the conflict, but that’s likely a significant undercounting. Half the population, nearly 25 million people, is expected to go hungry this year. Hundreds of thousands of people are directly threatened with starvation. More than 17 million children, out of 19 million, are not in school. A cholera epidemic rages. Malaria is endemic.

But no statistics can express the sense of pointlessness, of meaninglessness, that the war has left behind alongside the physical destruction.

In what can only be described as a melancholy case of selective blindness, the gaze of western mainstream and social media, distracted by other conflicts and causes has been turned away. The global conscience has appeared unmoved. The numbers are obscene, the silence more so.

El Fasher, in Sudan’s far western province of Darfur, is once again the world’s unacknowledged abyss. The UN warns of genocide; videos show unarmed men executed in cold blood, hospitals shelled, aid workers vanished, women violated, and civilians starved into submission. The Rapid Support Forces – the Janjaweed (colloquial Arabic for “devil riders”) in new fatigues – are methodically annihilating ethnic groups such as the Masalit. El Fasher was the Sudanese army’s last holdout in Darfur and its capture marks a milestone in the two yea long civil war, giving the RSF de facto control of more than a quarter of the territory.

Why the silence?

Because Sudan resists the narrative template that powers modern activism. There is no imperial villain, no clear coloniser or colonised, no simple choreography of oppression and resistance. The slaughter of black Africans does not fit the anti-Western moral geometry upon which contemporary protest movements are built. Sudanese bodies fall outside the moral lens of the global North even as they fall in their thousands.

This is not to rank suffering but to note the selectivity of empathy. Sudan’s tragedy lacks the aesthetic of victimhood that flatters Western guilt. The WHO pleads for hospitals; journalists beg for their detained colleagues. It all sounds chillingly familiar – yet no outrage follows. Perhaps because Sudan offers no convenient villain, no redemption arc, no social currency.

At the heart of the moral selectivity of the globalised conscience lies outrage as performance, empathy as branding. Sudan exposes the performative element of protest: empathy contingent on narrative utility. Its tragedy has no liturgy, no public ritual of belonging. It shows what our age truly worships: not justice, but self-expression masquerading as it. And in El Fasher’s unmarked graves lies the measure of this hypocrisy – a mute testimony to the moral vanity of a world that rages for Palestine, hashtags for Ukraine, and sleeps through Sudan.

In That Howling Infinite has touched on this dissonance before in The calculus of carnage – the mathematics of Muslim on Muslim mortality We wrote back then, in December 2023, when the Sudanese civil war has been raging for the best part of a year: “Call it moral relativism or “whataboutism” (or, like some conjuror’s trick, “don’t look here, look over there!) but it is not a matter of opinion, more a simple matter of observation, to point out that Muslims are in the main subdued when their fellow Muslims are killed by other Muslims … There has been no significant unrest in the West over the hundreds of thousands of Muslims killed by fellow Muslims (apart from a visceral horror of the violence inflicted upon civilians and prisoners by the jihadis of the Islamic State. No public outcry or social media fury, no angry street protests by left-wing activists of vacuous members by armchair, value-signaling clicktavists”.

Journey to an civil war

American journalist Anne Applebaum wrote very long essay the August edition of The Atlantic: Sudan … the most nihilistic war ever. She believes that Sudan’s devastating civil war shows what will replace the liberal order: anarchy and greed. Her essay reads like a missive from a civilisation already past the point of rescue. The country she describes is less a state than a geography of ruin — a landscape where the coordinates of morality, nationhood, and even information itself have come apart. The title is no exaggeration; it is diagnosis and prognosis both. Sudan, she argues, is not an aberration but a preview — the shape of the world when the liberal order finally collapses, when wars are fought not for gods or ideas but for bullion and bodies.

Sudan’s civil war began, at least formally, as a contest between two men: General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, commander of the regular army, and Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, known as Hemedti, who rose from the Janjaweed militias to command the Rapid Support Forces. Both were products of the same regime; both were once partners in repression. When they turned upon each other in 2023, the result was not ideological conflict but a kind of mutual devouring. Each accused the other of betrayal; each proceeded to loot, starve, and bomb the very population he claimed to protect.

Applebaum’s Sudan is not one country but many — an archipelago of fiefdoms and frontiers, each governed by whoever holds the nearest airstrip or gold mine. And gold, indeed, is the keyword: the new oil of an old desert. Sudan possesses vast deposits of it, and with them a vast invitation to corruption. Wagner mercenaries mine and smuggle it northward to fund Russia’s war in Ukraine. The United Arab Emirates bankrolls Hemedti’s RSF in exchange for access and influence. Egypt and Chad manoeuvre for position; Iran quietly re-enters the game. The Sudanese warlords themselves fight not to win the nation but to control the veins of the earth — the alluvial goldfields of Darfur and the Nile Basin that glitter beneath the dust like a curse.

Western governments, overstretched and inward-turned, offer gestures in place of policy. Applebaum notes that the world’s great democracies — once self-appointed custodians of human rights — now behave like distracted landlords. There is a knock at the door, another tenant murdered in the basement, but the owner is on the phone about something else.

In this sense, Sudan is less an anomaly than a mirror. It shows us what happens when international law becomes theatre, when moral outrage is rationed by proximity and profit. It is not merely a humanitarian disaster but a philosophical one: a demonstration that without belief — in justice, in shared reality, in the notion that human suffering still obliges response — politics decays into predation.

Applebaum’s prose, always measured, carries a note of exhausted mourning. The old ideological world — that twentieth-century drama of fascism, communism, and liberal democracy — at least believed in something, even if those beliefs destroyed millions. Today’s warlords believe in nothing at all. They are not even tyrants in the grand style; they are contractors of chaos, CEOs of slaughter, men who weaponise hunger for leverage and sell access to ruins.

What makes her essay so haunting is that Sudan’s nihilism feels contagious. The war may be geographically distant, but morally it is next door. The same disintegration of purpose infects the international response — the shrugging cynicism, the moral fatigue, the slow erosion of empathy. Applebaum’s Sudan is what remains when the “rules-based order” becomes a slogan muttered by people who no longer believe it themselves.

Coda: A Mirror in the Sand

The desert, Applebaum implies, has turned into a mirror of the world’s soul — reflecting its avarice, its indifference, its slow retreat from meaning.

What lingers after Applebaum’s account is not simply pity for Sudan, though that would be reason enough, but unease — the feeling that the world’s moral compass has slipped its pole and is spinning uselessly in our hands. Sudan is not the exception; it is the precedent. It is the world without illusion: borders drawn in dust, governments as rackets, truth dissolved into overlapping transparencies.

Once, wars were waged for empire, for creed, for revolution — each claiming, however falsely, to serve a higher cause. Now they are fought for metal, for markets, for motion itself. The soldiers are mercenaries, the civilians collateral, the nations staging grounds for someone else’s ledger. Applebaum’s overlapping maps are more than an image of Sudan’s confusion; they are an x-ray of a civilisation that no longer shares a moral reference point. We are all now drawing our own maps, colouring the world according to our comfort zones, overlaying them until the truth beneath is invisible.

And so Sudan becomes both tragedy and parable. Its gold mines glitter like tombs of the old order — the liberal dream of rules, rights, and reason — while above them drones and scavengers circle. A century ago, Conrad called it the horror; today it is merely another tab on a newsfeed. The anarchy is not confined to Khartoum or Darfur. It is spreading quietly through the arteries of global indifference, through our own fatigue, our own appetite for distraction.

If Applebaum is right, Sudan is not at the edge of the world but at its centre. The future, it turns out, is already here: gilded, godless, and for sale to the highest bidder.https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2025/09/sudan-civil-war-humanitarian-crisis/683563/

Postscript: selective empathy in a world of sorrow

Comparing the international outcry over Gaza to the silence on Sudan has been condemned as intellectual dishonesty. One comment on this post ran this:

“The mainstream media can stir outrage on any topic when its political masters and financial backers want it to. Why has it not done so in this instance? Follow the money is one rule of thumb. I assume it suits the powers that be to let the slaughter continue. I hope more people are inspired to become activists against this dreadful situation, but public opinion tends to follow the narrative manufactured by the media more than impel it. When it comes to pro-Palestinian activism it is the story of a long hard grind of dedicated protestors to get any traction at all against the powerful political and media interests which have supported the Israeli narrative and manufactured global consent for the genocide of Palestinians over many years. And still, although the tide is gradually turning, the West supports Israel to the hilt and crushes dissent. Using the silence in the media and in the streets over the slaughter in Sudan as an excuse to try and invalidate pro-Palestinian activism is a low blow and intellectually dishonest”.

This particular response is articulate and impassioned, but it also illustrates precisely the reflexive narrowing of moral vision that the comparison between Gaza and Sudan was meant to illuminate. The argument hinges on a familiar syllogism: that Western media outrage is never organic but always orchestrated (“follow the money”), that silence on Sudan therefore reflects elite indifference rather than public apathy, and that to highlight that silence is somehow to attack or “invalidate” the legitimacy of pro-Palestinian activism. It is a neat, closed circuit—morally reassuring, rhetorically watertight, but intellectually fragile.

For one thing, the claim that outrage over Gaza is a product of “a long hard grind” of dissenters battling pro-Israel hegemony may be partly true, but it fails to account for the asymmetry of moral attention. Why, if media outrage can be manufactured at will, does it attach so selectively? Why is one tragedy magnified until it becomes the world’s moral touchstone, while another, numerically and humanly no less immense, barely registers? This is not to invalidate solidarity with Gaza—it is to interrogate the mechanisms by which empathy itself is distributed, channelled, and constrained.

The “follow the money” thesis also misses something subtler and more disturbing. Western silence on Sudan is not an act of conspiracy but of exhaustion: no villains clearly marked, no sides easily named, no tidy narrative of good and evil to moralise upon. Sudan’s war—fragmented, internecine, post-ideological—does not lend itself to hashtags or flags on Instagram profiles. It is a horror too complex to package and too distant to own. By contrast, Gaza offers clarity, identity, and the reassuring architecture of blame: victims and oppressors, martyrs and monsters, the colonial morality play in perfect focus.

Thus, when critics accuse those who draw this comparison of “intellectual dishonesty,” they mistake the argument. To juxtapose Gaza and Sudan is not to weigh one body count against another, or to diminish Palestinian suffering. It is to expose the limits of our moral imagination – how empathy becomes performative when it is contingent on narrative simplicity or political fashion.

In Sudan, the gold glitters under the rubble. Warlords, mercenaries, and foreign patrons all claw for it while millions starve. In Gaza, the ruins are televised, moralised, and weaponised. Both are human catastrophes, but only one has an audience.

The point, then, is not that activists for Gaza are wrong—it is that they are lonely. If their struggle truly seeks a universal human justice, it must be capacious enough to include Darfur, Khartoum, El Fasher—to grieve what the cameras do not show. Otherwise, our compassion becomes another form of exceptionalism: the selective virtue of those who need their tragedies to fit the script.

In truth, to compare Gaza and Sudan is not to rank suffering or diminish solidarity, but to expose the limits of our moral bandwidth. Gaza compels because its story is legible—villains, victims, a script the world knows by heart. Sudan confounds because it is too fractured, too many nations within one, too little meaning to hold. There is no clear narrative, only greed, hunger, and gold buried beneath the ruins.

The real dishonesty is not in caring for Gaza, but in mistaking selective empathy for universal conscience. If our outrage depends on simplicity, we risk turning compassion into performance – mourning only what the cameras show, and averting our eyes from what they cannot.

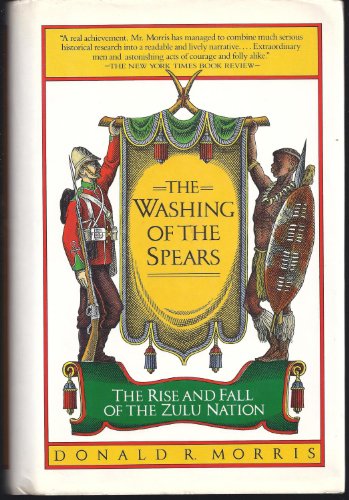

The Defense of Rorke’s Drift, Alphonse de Neuville, 1880

The Defense of Rorke’s Drift, Alphonse de Neuville, 1880