“We are cursed to live in a time of great historical significance: when future historians look back at 2023, the distinguishing feature of this year will likely be the recurrence of ethnic cleansing on a vast scale”.

Thus wrote Unherd columnist and former war correspondent Aris Roussinos in December. 2023, but he would draw the same conclusion in 2024 and in 2025. He notes that ethnic cleansing is taking place on a vast scale in many parts of the world. Yet, apart from the current outrage at Israel’s war on Hamas in Gaza, turbocharged as it is by unprecedented and arguably one-sided mainstream and social media coverage, international reaction has been muted to the point of indifference. Roussinos’ article is republished below, and the following overview is inspired by and draws on his observations.

The term ethnic cleansing is elusive and politically charged. In an age of endemic conflict, identity politics and competing narratives, it has become a contested and often diluted concept invoked with increasing frequency. Yet, it remains undefined in law. Unlike genocide or war crimes, it has never been codified as a distinct offence under international law, and so its use is contested.

A United Nations Commission of Experts investigating violations during the wars in the former Yugoslavia offered the most widely cited descriptions. In its interim report it defined ethnic cleansing as “rendering an area ethnically homogeneous by using force or intimidation to remove persons of given groups from the area.” In its final report the following year, the Commission elaborated: it is “a purposeful policy designed by one ethnic or religious group to remove by violent and terror-inspiring means the civilian population of another ethnic or religious group from certain geographic areas.” What is clear in these descriptions is that ethnic cleansing is deliberate, systematic, and political in nature.

The Commission also catalogued the methods through which such policies are carried out. They include murder, torture, arbitrary arrest and detention, extrajudicial executions, rape and sexual violence, severe injury to civilians, confinement of populations in ghettos, forcible deportation and displacement, deliberate military attacks or threats of attacks on civilian areas, the use of human shields, the destruction and looting of property, and assaults on hospitals, medical staff and humanitarian organisations such as the Red Cross and Red Crescent. The Commission concluded that these acts could amount to crimes against humanity, war crimes, and in some instances, fall within the meaning of the Genocide Convention.

Many people today use the term ethnic cleansing interchangeably with genocide, since both involve the violent removal and destruction of communities and often lead to similar outcomes of death, displacement, and cultural erasure. Ethnic cleansing, which refers to the forced expulsion of a group from a territory through intimidation, violence, or coercion, frequently overlaps with acts that fall under the 1948 UN Genocide Convention, such as mass killings and the destruction of cultural or religious life. This blurring of concepts reflects not only the moral outrage provoked by such crimes but also frustration at the narrowness of legal categories, which can leave survivors feeling their suffering has been minimized by technical distinctions. Historical cases illustrate how the line between the two has often been perilously thin: the mass deportations and killings of Armenians in 1915, which many scholars and states regard as genocide and even describe as a holocaust – though Türkiye denies it and Israel avoids official recognition for fear of diluting the unique status of the Shoah – the expulsions and massacres of Bosnian Muslims in the 1990s, and the flight of the Rohingya from Myanmar all show how ethnic cleansing has so often carried genocidal dimensions – as is particularly the case today with the war in Gaza which has polarized and politicized ordinary people and activists alike worldwide who have through lack of knowledge or opportunism conflated the two.

Yet it is important to recognize that genocide and ethnic cleansing are not strictly interchangeable. Genocide requires proof of an intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnic, racial, or religious group, whereas ethnic cleansing focuses primarily on expulsion, which may or may not involve that deeper intent to annihilate. Ethnic cleansing can amount to genocide when the purpose is to eradicate a group, but not all instances meet this threshold. In public discourse, however, people motivated more by empathy and emotion than by detailed knowledge of history or law are often inclined to conflate the two, since the lived experience of the victims—violence, displacement, and cultural obliteration – appears indistinguishable from destruction itself. More informed observers, by contrast, emphasize legal precision and historical context, recognizing that while the outcomes often overlap, preserving the distinction remains vital for accurate analysis and accountability.

The moral revulsion ethnic cleansing excites is the natural and humane reaction, but historically and also presently, it is not an uncommon phenomenon. For the American sociologist and academic Michael Mann, ethnic cleansing is the natural consequence of modernity, “the dark side of democracy”: a recurring temptation of the modern nation-state. The following sections provided examples from the last thirty years, followed by a survey of instances of ethnic cleansing during the early to mid Twentieth Century. They describe how ethnic cleansing is not only a crime of forced removal and murder but also an assault on identity, memory, and the very visibility of a people.

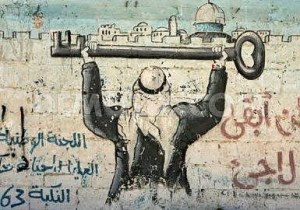

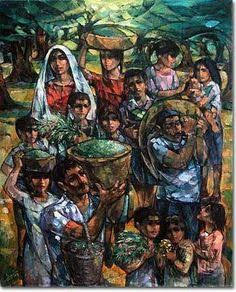

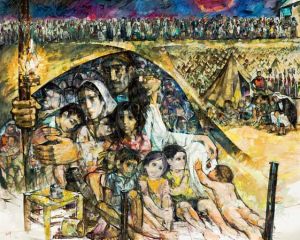

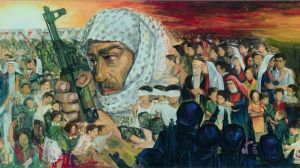

[The featured picture at the head of this blog post is one of Palestinian artist Ismail Shammout’s striking illustrations of Al Nakba, the dispossession of tens of thousands of Palestinian Arabs during Israel’s war of independence, from In That Howling Infinite’s Visualizing the Palestinian Return – the art of Ismail Shammout]. More of his art is included below]

Expulsion, eradication and exile

The Wars of the Yugoslav Succession in the 1990s – encompassing Croatia, Bosnia, and Kosovo – offer a clear illustration of ethnic cleansing in a modern European context. As Yugoslavia disintegrated, political and military leaders pursued campaigns aimed at creating ethnically homogeneous territories, often through the systematic targeting of civilians. In Bosnia, Serb forces carried out mass killings, forced deportations, rape, and the deliberate destruction of homes, schools, and cultural heritage sites, culminating in the Srebrenica massacre of 1995, in which more than 8,000 Muslim men and boys were killed. In Croatia and Kosovo, similar tactics were deployed: ethnic minorities were expelled, villages razed, and communities terrorised into flight. The International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) documented and prosecuted these actions as crimes against humanity and war crimes, establishing that the campaigns were not chaotic consequences of war, but deliberate, coordinated policies of ethnic removal. The tribunal’s rulings provide a legal benchmark for understanding ethnic cleansing as the purposeful removal of populations through violence, intimidation, and coercion, a pattern that recurs across history and geography—from the forced expulsions of Armenians in 1915, to the population exchanges of Greece and Turkey in 1923, to the contemporary displacement of Rohingya, Palestinians, Ukrainians, and Afghans. These cases demonstrate that ethnic cleansing combines physical violence, forced migration, and cultural erasure, often leaving long-term social, political, and demographic scars that endure generations after the immediate conflict.

Sudan has witnessed repeated waves of ethnic cleansing over recent decades, most infamously in Darfur in the early 2000s, when government-backed Arab Janjaweed militias targeted non-Arab communities with systematic violence. Villages were burned, civilians massacred, women subjected to mass rape, and more than 2.5 million people displaced, in what the International Criminal Court later described as crimes against humanity, war crimes, and genocide. The displacement and destruction in Darfur followed earlier campaigns of forced removal during Sudan’s long north–south civil war, where entire communities in the south and Nuba Mountains were uprooted by aerial bombardment, scorched earth tactics, and starvation sieges. Today, ethnic cleansing has returned with devastating intensity: since April 2023, renewed fighting between the Sudanese Armed Forces and the Rapid Support Forces (successors to the Janjaweed) has triggered mass atrocities, including the killing of thousands and the flight of more than 7 million civilians, many across borders into Chad, South Sudan, and Egypt. Reports of targeted massacres against non-Arab groups in West Darfur suggest continuity with earlier campaigns, underscoring how ethnic cleansing in Sudan is not an isolated event but a recurring feature of its violent political landscape.

The Rohingya expulsions in Myanmar provide a stark contemporary example of ethnic cleansing. Since 2017, Myanmar’s military has carried out systematic campaigns of violence, including mass killings, sexual violence, arson, and the destruction of villages, aimed at driving the Rohingya Muslim population from Rakhine State. More than 700,000 Rohingya have fled to neighbouring Bangladesh, creating one of the world’s largest refugee crises. The violence has been accompanied by measures of cultural and social exclusion: denial of citizenship, restrictions on movement, and the erasure of Rohingya identity from official records. The United Nations and international observers have described these actions as ethnic cleansing, noting the deliberate intent to remove an entire ethnic group from a geographic area, while some investigators have determined that elements of the campaign meet the criteria for genocide.

Armenia and its surrounding regions have been scarred by cycles of ethnic cleansing for more than a century. The Armenian genocide of 1915–1916, carried out by the Ottoman Empire, combined forced deportations, massacres, and cultural destruction with the intent of removing Armenians from their ancestral lands in Anatolia. More than a million were killed or died on death marches, and countless others were scattered into diaspora communities across the Middle East, Europe, and the Americas. Later, in the Soviet period, Armenians and Azerbaijanis experienced repeated forced movements, with pogroms and expulsions erupting during times of political instability. Most recently, the 2023 offensive by Azerbaijan in Nagorno-Karabakh resulted in the flight of almost the entire Armenian population of the enclave—around 120,000 people—into Armenia proper, effectively erasing a centuries-old community. These waves of displacement illustrate how ethnic cleansing in Armenia is not confined to the past but has recurred across generations, leaving lasting demographic, cultural, and political consequences for the region.

During the past two years, mass expulsions from neighbouring countries returned large numbers of Afghans to Taliban-run Afghanistan. Pakistan has deported nearly half a million Afghans; Iran has driven out hundreds of thousands more. What is packaged as “repatriation” is, in many cases, forced displacement: exiles who had tenuous livelihoods, access to education, or limited civil freedoms in exile are now returned to a polity where the rights — especially the rights of women and girls — are ruthlessly curtailed. The Taliban’s record on gender is well known: it controls a society where women are barred from education and work, forced into early marriages, and denied even minimal public freedoms. Public-life prohibitions and systematic punishments disproportionately harm women and girls. Returning families are therefore being pushed into what many observers describe as among the worst possible places in the world for women — a profoundly gendered and life-threatening form of displacement.

The erasure of culture and historical memory

Like genocide, ethnic cleansing may not be limited the physical expulsion or eradication of people. It can be political, cultural and geographical, and often works through more insidious forms of erasure.

China’s policies in Xinjiang are an example. It has renamed at least 630 villages in Xinjiang, erasing references to Uyghur culture in what human rights advocates say is a systematic propaganda rebrand designed to stamp out the Muslim minority group’s identity. Human Rights Watch has documented a campaign of renaming thousands of villages across the region, stripping out references to Uyghur religion, history and culture. At least 3,600 names have been altered since 2009, replaced by bland slogans such as “Happiness,” “Unity” and “Harmony.” Such bureaucratic changes appear mundane, but they are part of a systematic project to erase Uyghur identity from the landscape itself.

Ukraine illustrates another, more violent dimension of contemporary ethnic cleansing. Russia is coercively integrating five annexed Ukrainian regions — an area the size of South Korea — into its state and culture. Ukrainian identity is being wiped out through the imposition of Russian schooling and media, while more than a million Russian citizens have been settled illegally into the occupied zones. At the same time, some three million Ukrainians have fled or been forced out. Torture centres have been established, with one UN expert describing their use as “state war policy.” Russian forces have employed sexual violence, disappearances and arbitrary detentions, and carried out massacres. Civilian deaths officially stand at around 10,000, but independent estimates suggest a figure closer to 100,000. Homes and businesses have been seized and redistributed to the cronies of Russian officials and officers. On top of these abuses, thousands of Ukrainian children have been taken from their families and deported into Russia for adoption and assimilation, with the threat that when they reach 18 they will be conscripted into the Russian military. This programme of child transfers has been declared a war crime by international courts, and represents perhaps the most chilling element of the campaign to erase Ukrainian identity across generations. Russian propagandists, including ideologues such as Alexander Dugin, routinely describe Ukrainians as “vermin” to be eliminated — language that many experts say is consistent with genocidal intent.

The long arm of history

Historical precedent is sobering, underscoring how entrenched practices definable as ethnic cleansing are. Some examples follow.

The Armenian genocide of 1915–1916 is a historical example where the term “ethnic cleansing” can be applied alongside, though not identical to, the legal concept of genocide. Ottoman authorities systematically deported, massacred, and starved Armenians from their ancestral homelands in Anatolia, often under the guise of military necessity. Entire villages were emptied, survivors forced on death marches into the Syrian desert, and cultural and religious heritage deliberately destroyed. These actions aimed to remove the Armenian population from the territory of the Ottoman Empire, making the region ethnically and religiously homogeneous, which aligns closely with contemporary definitions of ethnic cleansing. The genocide combined mass killing with forced displacement and cultural erasure, illustrating how ethnic cleansing and genocide can overlap in both intent and method. (See The Fall of the Ottoman Empire and the birth of Türkiye)

The Armenian case also illustrates how recognition of genocide is often bound up not only with history but with contemporary politics. Türkiye continues to deny that the mass deportations and killings of Armenians in 1915 amounted to genocide, framing them instead as wartime relocations within the collapsing Ottoman Empire. Israel, despite wide acknowledgment among its own scholars of the genocidal character of the events, has avoided official recognition, partly out of diplomatic considerations toward Türkiye, once a key regional ally, but also out of concern that equating the Armenian tragedy with the Shoah might dilute the unique historical and moral status attached to the Holocaust in Jewish memory and international discourse. This reluctance is not unique to Israel: several states have long hesitated to employ the term “genocide” for fear of straining relations with Ankara or complicating their own foreign policy priorities. Such debates demonstrate how the line between ethnic cleansing and genocide is not only a matter of legal precision but also of political narrative, with governments and institutions sometimes reluctant to apply the most condemnatory labels even where evidence overwhelmingly supports them.

As the Northern Irish writer Bruce Clark observed in his excellent book Twice A Stranger on the euphemistically termed “population exchanges” between Greece and Turkey exactly a century ago, “Whether we like it or not, those of us who live in Europe or in places influenced by European ideas remain the children of Lausanne,” the 1923 peace treaty, finalizing the dismemberment of the Ottoman Empire after the First World War, which decreed a massive, forced population movement between Turkey and Greece”, and in effect, One and a quarter million Greek Orthodox Christians were removed from Anatolia, the heartland of the new republic of Türkiye, and nearly 400,000 Muslims from Greece, in a process overseen by the Norwegian diplomat Fridtjof Nansen leading a branch of the League of the Nations which would later – perhaps ironically – evolve into today’s UNHCR.

During the Second World War, Soviet Union alone deported half a million Crimean Tatars and tens of thousands of Volga Germans to Siberia. In 1945, the victorious Allied powers oversaw the removal of some 30 million people across Central and Eastern Europe to create ethnically homogeneous states. At Yalta and Potsdam, Britain, the US, and the Soviet Union endorsed the expulsion of 12 million Germans, over 2 million Poles, and hundreds of thousands of Ukrainians, Hungarians, and Finns.

The partition of British India in 1947 produced one of the largest and bloodiest forced migrations in modern history. As the new states of India and Pakistan were created, an estimated 12 to 15 million people crossed borders in both directions – Muslims moving into Pakistan, Hindus and Sikhs into India – in a desperate effort to reach what they hoped would be safer ground. The upheaval was marked by extreme communal violence, massacres, abductions, and sexual assaults. Between 500,000 and 1 million people are thought to have been killed, and millions more were uprooted from ancestral homes they would never see again. The trauma of Partition continues to shape Indian and Pakistani national identities, as well as the politics of South Asia to this day. (See Freedom at Midnight (2): the legacy of partition) and Freedom at Midnight (1): the birth of India and Pakistan

The dismemberment of Mandate Palestine by the new state of Israel, Jordan and Egypt in 1948 brought two simultaneous mass displacements that remain unresolved. During the first Arab–Israeli war more than 700,000 Palestinians fled or were expelled from their homes in what became Israel. Known as the Nakba or “catastrophe,” this created a vast refugee population now numbering in the millions, many still stateless. Jews living in what is now the Old City and East Jerusalem, and the West Bank seized by Jordan were expelled. Jews living across the Arab world in Iraq, Yemen, Egypt, Libya, Syria and elsewhere – faced growing hostility, persecution, and expulsion. Between 1948 and the 1970s, an estimated 800,000 to 1,000,000 Jews left or were forced out, many stripped of property and citizenship. Most resettled in Israel, where their presence profoundly altered the country’s politics and culture. Palestinians and Jews alike endured dispossession, trauma and exile, and both experiences fuel competing narratives of grievance that continue to define the conflict.

Israelis are themselves, for the most part, the product of 20th-century ethnic cleansings, in the Middle East as well as Europe: indeed the descendants of Middle Eastern Jews, like the Security Minister Itamar Ben-Gvir, are the country’s most radical voices on the Palestinian Question. But unlike the Mizrahim, and displaced of Eastern and south-eastern Europe, the Palestinians have no Israel to go to. There is no Palestinian state waiting to absorb them. Indeed, for Gaza’s population, the vast majority of whom descend from refugees from what is today Israel, Gaza was their place of refuge, and the 1948 Nakba the foundational event in their sense of Palestinian nationhood. For all that ethnic cleansing punctuates modern history, there is no precedent for such a process of double displacement, and the political consequences cannot at this stage be determined. We may assume they will not be good, and an analogue to Europe’s post-war neighbourly relations will not be found.

Conclusion: The Age of Dispossession

In many historical cases, expulsions, however brutal, were stabilized by the existence of ethnic homelands ready to absorb the displaced. Refugees were incorporated into nationalist projects in Greece and Türkiye, or into newly homogenized states such as Poland and Ukraine, where they became central to the shaping of modern politics. The Karabakh Armenians driven into Armenia may follow this precedent, potentially reshaping the political order of a small and embattled state.

Ethnic cleansing in the twenty-first century, however, combines these older methods with new techniques. Violence, rape, deportation, and massacre continue, but are now accompanied by cultural erasure, bureaucratic renaming, engineered resettlement, propaganda, and the deliberate targeting of children for assimilation. Unlike many twentieth-century precedents, today’s displaced populations often have nowhere safe to go, forced into territories with no protective homeland or into environments of repression, creating open-ended cycles of dispossession. The erasure of identities in Xinjiang, the coercive integration of Ukrainian territories, the expulsion of Rohingyas and Afghans, the depopulation of Karabakh, and the looming threat of Gaza – where Palestinians face the looming threat of another mass displacement, echoing the 1948 Nakba – collectively demonstrate that ethnic cleansing is not a relic of the past.

It remains a recurring feature of our age – modern history is indeed built upon exodus and displacement – and its human cost is profound and incalculable.

© Paul Hemphill 2024,2025. All rights reserved

Postscript … Al Nakba, a case study in dispossesion

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, European Jews came to a land that was already inhabited by another, different people. Over two decades, they forced the guarantor power out by terrorism and took the land by conquest, expelling most of its original inhabitants by force. They have sowed their share of wind, too. Both sides want all the land for themselves.

Al Nakba, is the Arabic name for the “catastrophe” that befell the Arab inhabitants of Mandate Palestine during the war that was fought between Arabs and Jews in 1947-1948, resulting in the expulsion of upwards of 700,000 Arab Palestinians. That it happened is incontrovertible. But the facts, even those that are attested to by all reputable politicians and academic authorities, including Israelis, have long been subject to doubt and distortion by all sides of what has since been called “The Middle East Conflict” – notwithstanding that there have been conflicts in the Middle East more devastating and bloodier in terms of destruction and mortality including in Lebanon, Iraq, Syria, Algeria, Libya, and Sudan.

I do not to intend here to retell the history of Al Nakba. There many accounts available in print including those by Arab and Israeli authors, and in film, particularly an excellent documentary broadcast by Al Jazeera in May 2013 and repeated often?

June 17th, 2018, I wrote about it in a Facebook post:

Al Nakba did not begin in 1948. Its origins lie over two centuries ago….

So begins this award-winning series from Al Jazeera, a detailed and comprehensive account of al Nakba, the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948 and the dispossession and expulsion of the Palestinians who lived within its borders.

It is a well-balanced narrative, with remarkable footage, that will not please the ardent partisans of both sides who prefer their story of 1948 to be black and white.

Revisionist Israeli historians Ilan Pappe, Avi Shlaim, and Teddy Katz describe the ruthless and relentless military operations to clear and cleanse “Ha’aretz”, the land, of its Arab inhabitants and their history, whilst Palestinian historians tell the story from the Palestinian perspective, describing the critical failings of Palestinian’s political leaders and neighbouring Arab governments. Elderly Palestinians who were forced into exile and to camps in Jordan and Lebanon tell their sad stories of starvation and poverty, violence and death, and of terrible sadness, homesickness and longing that the passing years and old age have never diminished.

“When I left my homeland, I was a child. Now, I’m an old man. So are my children. But did we move forward? Where is our patriotism? Patriotism is about the pockets of our current leaders. They build high buildings and go to fancy banquets. They pay thousands for their children’s weddings”. Refugee Hosni Samadaa.

“We’re repeating the same mistakes. Before 1948 the Palestinian National Movement was split on the basis of rival families. Today, it is split into different parties over ideology, jurisdiction and self-interests. We didn’t learn our lesson. We were led by large, feudal landowners. Today, we are led by the bourgeoisie. Before 1948, we were incapable of facing reality. Today, we are just as inept. Before 1948, people chose the wrong leadership. And today, we are following the wrong leaders”. Researcher Yusuf Hijazi.

https://www.aljazeera.com/program/featured-documentaries/2013/5/29/al-nakba

I republish below Roussinos’ article in full, also a brief but comprehensive account about Al Nakba by economist and commentator Henry Ergas.

- The hand that signed the paper

- We did not weep when we were leaving – the poet of Nazareth

- Visualizing the Palestinian Return – the art of Ismail Shammout

- تصور عودة الفلسطينيين – فن إسماعيل شموط

- Freedom at Midnight (1): the birth of India and Pakistan

- Freedom at Midnight (2): the legacy of partition

- Lebensraum Redux – Hamas’ promise of the hereafter

The truth about the ethnic cleansing in Gaza – modern Europe was built on exodus and displacement

We are cursed to live in a time of great historical significance: when future historians look back at 2023, the distinguishing feature of this year will likely be the recurrence of ethnic cleansing on a vast scale. In just the past few months, Pakistan has deported nearly half a million Afghan migrants, while Azerbaijan has forced 120,000 Armenians — the statelet’s entire population — from newly-conquered Karabakh, both to broad international indifference. As the UNHCR has warned, the forced expulsion — that is, the ethnic cleansing — of Gaza’s Palestinian population is now the most likely outcome of the current war.

With no prospect of Palestinians and Israelis living together peaceably, anything short of absolute military victory unacceptable to both the Israeli government and its voters, but no meaningful plan for who will rule the uninhabitable ruins of post-war Gaza, the only realistic solution to the Palestinian problem, for Israel, is the total removal of the Palestinians. As Israel’s former Interior Minister has declared: “We need to take advantage of the destruction to tell the countries that each of them should take a quota, it can be 20,000 or 50,000. We need all two million to leave. That’s the solution for Gaza.”

Israeli officials have not been shy in promoting this outcome to a war, according to the President Isaac Herzog, for which “an entire nation… is responsible”. Israel’s agriculture minister Avi Dichter has asserted that “We are now rolling out the Gaza Nakba,” adding for emphasis that the result of the war will be “Gaza Nakba 2023. That’s how it’ll end.”Israel’s Intelligence Ministry has published a “concept paper” proposing the expulsion of Gaza’s entire population to the Sinai desert, and Israeli diplomats have been trying to win international support for this idea. According to the Israeli press, Israeli officials have sought American backing for a different plan to distribute Gaza’s population between Egypt, Turkey, Iraq and Yemen, tying American aid to these countries’ willingness to accept the refugees. In a Wall Street Journal opinion piece, two Israeli lawmakers have instead urged Western countries — particularly Europe — to host Gaza’s population, asserting that: “The international community has a moral imperative—and an opportunity—to demonstrate compassion [and] help the people of Gaza move toward a more prosperous future.” The outcome for Gaza’s Palestinians does not appear to be in doubt: what remains to be haggled over is their final location.

The only actor that can prevent the ethnic cleansing of Gaza is the United States, and for domestic political reasons it is disinclined to do so. While the Biden administration declaresit does not support “any forced relocation of Palestinians outside of the Gaza Strip”, it is not taking any action to prevent it. If the expulsion of Gaza’s 2.3 million population comes to pass, the result will be the most significant instance of ethnic cleansing in a generation, which will define Biden’s presidency for future historians. Yet outrage over such events is selective. It is not entirely true, as some Middle Eastern commentators claim, that Western complicity in the looming ethnic cleansing of Gaza highlights a lesser interest in Arab or Muslim lives: the Armenian case highlights that eastern Christians also barely flicker on the world’s moral radar.

This week’s awarding of the right to host next year’s COP29 climate conference to Azerbaijan, just a few months after its ethnic cleansing of Karabakh, reminds us that the supposed international taboo on the practice does not, in reality, exist. When ethnic cleansing is permissible, and when it is a war crime, depends, it seems, on who is doing it, and to whom. Azerbaijan is oil-rich, useful to Europe, and able to buy favourable Western coverage; Armenia is poor, weak and friendless in the world. Similarly, the extinction of much of the Christian population of the Middle East as a result of the chaos following the Iraq War won very little international attention or sympathy: communities which survived in their ancient homelands from Late Antiquity, riding out the passage of Arab, Mamluk, Ottoman and European imperial rule, did not survive the American empire.

Yet while the moral revulsion such events excite is the natural and humane reaction, ethnic cleansing is less rare an event than the crusading military response to its Nineties occurrence in the Balkans may make us think. For the sociologist Michael Mann, ethnic cleansing is the natural consequence of modernity, “the dark side of democracy”. As the Northern Irish writer Bruce Clark observed in his excellent book Twice A Stranger on the euphemistically termed “population exchanges” between Greece and Turkey exactly a century ago, “Whether we like it or not, those of us who live in Europe or in places influenced by European ideas remain the children of Lausanne,” the 1923 peace treaty “which decreed a massive, forced population movement between Turkey and Greece”. One and a quarter million Greek Orthodox Christians were removed from Anatolia, and nearly 400,000 Muslims from Greece, in a process overseen by the Norwegian diplomat Fridtjof Nansen leading a branch of the League of the Nations which would later — perhaps ironically — evolve into today’s UNHCR.

It was a cruel process, wrenching peoples from ancestral homelands in which they had lived for centuries, even millennia— and by the end of it half a million people were unaccounted for, presumably dead. Yet it was viewed as a great diplomatic triumph of the age, perhaps with good reason: without meaningful minorities on each side of each others’ borders to stoke tensions, Greece and Turkey have not fought a war in a century. Indeed, as late as 1993, the Realist IR scholar John Mearsheimer could propose a “Balkan Population Exchange commission” for the former Yugoslavia explicitly modelled on the 1923 precedent, asserting that “populations would have to be moved in order to create homogeneous states” and “the international community should oversee and subsidize this population exchange”. For the younger Mearsheimer, ethnic cleansing was the only viable solution to Yugoslavia’s bloody and overlapping ethnic map: “Transfer is a fact. The only question is whether it will be organized, as envisioned by partition, or left to the murderous methods of the ethnic cleansers.” Thirty years later, however, Mearsheimercondemns Israel’s planned expulsions from Gaza outright.

There is a dark irony here: the forced expulsion of peoples is an affront to liberal European values, yet it is rarely acknowledged that our modern, hitherto peaceful and prosperous Europe is built on the foundation of ethnic cleansing. Perhaps the ramifications of such a truth are too stark to bear, yet it is nevertheless the case that the peaceable post-1945 order depended on mass expulsions for its stability. Using the 1923 exchange as their explicit model, the victorious allies oversaw the forced removal of 30 million people from their homes in Central and Eastern Europe towards newly homogeneous ethnic homelands they had never seen. At the Yalta and Potsdam conferences, Britain, the United States and the Soviet Union settled upon the expulsion of 12 million Germans, more than 2 million Poles and hundreds of thousands of Ukrainians, Hungarians and Finns from their ancestral homes.

As Churchill declared in Parliament in 1944, “expulsion is the method that, so far as we have been able to see, will be the most satisfactory and lasting. There will be no mixture of populations to cause endless trouble, as has been in the case of Alsace-Lorraine. A clean sweep will be made.” Only two years later, once the Cold War had begun and the Soviet Union and its vassal Poland become a rival, did Churchill fulminate against the “enormous and wrongful inroads upon Germany, and mass expulsions of millions of Germans on a scale grievous and undreamed of” by “the Russian-dominated Polish Government”. In ethnic cleansing, as in so many other things, political context is the final arbiter of morality.

But as a result, Germany has never since unsettled Europe with revanchist dreams; both Poland and Western Ukraine became, for the first time in their histories, ethnically homogenous entities. As the Ukrainian-Canadian historian Orest Subtelny has observed, the forced separation of Poles and Ukrainians, once locked in bitter ethnic conflict against each other, has led to today’s amicable relationship: “It seems that the segregation of the two peoples was a necessary precondition for the development of a mutually beneficial relationship between them. Apparently the old adage that ‘good fences make for good neighbors’ has been proven true once more.” That we have forgotten the vast scale of the forced expulsions which established Europe’s peaceful post-war order is, in a strange way, a testament to their success.

Yet what made the mass expulsions following the First and Second World Wars broadly successful was that those expelled at least had ethnic homelands to receive them. In Greece and Turkey, the refugees fully adopted the ethnic nationalism of their new countries, in Greece providing the bedrock of later republican sympathies, and in Turkey the core support for both secular Kemalist nationalism and occasional bouts of military rule. In the newly-homogenous Poland and Ukraine, refugees shorn of their previous local roots and at times ambiguous ethnic identities fully adopted in recompense a self-identification with their new nation-states which has helped define these countries’ modern politics. The 120,000 Karabakh refugees will likely become a political bloc in tiny Armenia, affecting the country’s future political order in ways yet hard to discern.

Israelis are themselves, for the most part, the product of 20th-century ethnic cleansings, in the Middle East as well as Europe: indeed the descendants of Middle Eastern Jews, like the Security Minister Itamar Ben-Gvir, are the country’s most radical voices on the Palestinian Question. But the Palestinians, like the ethnic French narrator of Houellebecq’s Submission, have no Israel to go to. Unlike the 20th century displaced of Eastern and south-eastern Europe, there is no Palestinian state waiting to absorb them. Indeed, for Gaza’s population, the vast majority of whom descend from refugees from what is today Israel, Gaza was their place of refuge, and the 1948 Nakba the foundational event in their sense of Palestinian nationhood. For all that ethnic cleansing punctuates modern history, there is no precedent for such a process of double displacement, and the political consequences can not at this stage be determined. We may assume they will not be good, and an analogue to Europe’s post-war neighbourly relations will not be found.

Egypt’s disinclination to host two million Gazan refugees is not merely a matter of solidarity, but also self-preservation: flows of embittered Palestinian refugees helped destabilise both Lebanon, where their presence set off the country’s bloody ethnic civil war, and Jordan, where they make up the demographic majority. It is doubtful too, given the recent tenor of its politics, that Europe will be eager to receive them, no matter how humanitarian the language with which Israeli officials couch their planned expulsion. Rendered stateless, driven from their homes and brutalised by war, Gaza’s refugees remain unwanted by the world, perhaps destined to become, as the Jews once were, a diaspora people forever at the mercy of suspicious hosts.

A terrible injustice for the Palestinians, their ethnic cleansing may yet provide Israel with a measure of security, even as it erodes the American sympathy on which the country’s existence depends. The broader question, perhaps, is whether or not the looming extinction of Palestinian life in Gaza, like the expulsion of Karabakh’s Armenians, heralds the beginning of a new era of ethnic cleansing, or merely the settling of the West’s unfinished accounts. Like the movements which bloodily reshaped Central Europe, Israel’s very existence is after all a product of the same nationalist intellectual ferment of fin-de-siècle Vienna. In 1923, while acknowledging its necessity, the British Foreign Secretary Lord Curzon called the Greco-Turkish population exchange “a thoroughly bad and vicious [idea] for which the world would pay a heavy penalty for a hundred years to come”. Exactly a century later, Gaza’s Palestinians look destined to become the final victims of Europe’s long and painful 20th century

Nakba, where Palestinian victim mythology began

‘Nakba Day’ was commemorated this week with even more vehemence than usual. The greatest tragedy is that the Palestinian people who fled remain frozen in time.

Henry Ergas, The Australian, 18th May 2024

Protestors at a Sydney rally to mark the anniversary of the ‘Nakba’. David Gray/AFP

On Wednesday, “Nakba Day” was commemorated around the world with even more vehemence than usual as outpourings of hatred against Israel, sprinkled with ample doses of anti-Semitism, issued from screaming crowds.

What was entirely missing was any historical perspective on the Nakba – that is, the displacement, mainly through voluntary flight, of Palestinians from mandatory Palestine. Stripped out of its broader context, the event was invested with a uniqueness that distorts the processes that caused it and its contemporary significance.

It is, to begin with, important to understand that the displacement of Palestinians was only one facet of the sweeping population movements caused by the collapse of the great European land empires. At the heart of that process was the unravelling of the Ottoman Empire, which started with the Greek war of independence in 1821 and accelerated during subsequent decades.

As the empire teetered, religious conflicts exploded, forcing entire communities to leave. Following the Crimean War of 1854-56, earlier flows of Muslims out of Russia and its border territories became a flood, with as many as 900,000 people fleeing the Caucasus and Crimea regions for Ottoman territory. The successive Balkan wars and then World War I gave that flood torrential force as more than two million people left or were expelled from their ancestral homes and sought refuge among their co-religionists.

The transfers reshaped the population geography of the entire Middle East, with domino effects that affected virtually every one of the region’s ethnic and religious groups.

The formation of new nation-states out of what had been the Ottoman Empire then led to further rearrangements, with many of those states passing highly restrictive nationality laws in an attempt to secure ethnic and religious homogeneity.

Nothing more starkly symbolised that quest for homogeneity than the Convention Concerning the Exchange of Greek and Turkish Populations signed on January 30, 1923. This was the first agreement that made movement mandatory: with only a few exceptions, all the Christians living in the newly established Turkish state were to be deported to Greece, while all of Greece’s Muslims were to be deported to Turkey. The agreement, reached under the auspices of the League of Nations, also specified that the populations being transferred would lose their original nationality along with any right to return, instead being resettled in the new homeland.

Underlying the transfer was the conviction, articulated by French prime minister (and foreign minister) Raymond Poincare, that “the mixture of populations of different races and religions has been the main cause of troubles and of war”, and that the “unmixing of peoples” would “remove one of the greatest menaces to peace”.

That the forced population transfers, which affected about 1.5 million people, imposed enormous suffering is beyond doubt. But they were generally viewed as a success. Despite considerable difficulties, the transferred populations became integrated into the fabric of the recipient communities – at least partly because they had no other option. At the same time, relations between Turkey and Greece improved immensely, with the Ankara Agreements of 1930 inaugurating a long period of relative stability.

The result was to give large-scale, permanent population movements, planned or unplanned, a marked degree of legitimacy.

Thus, the formation of what became the Irish Republic was accompanied by the flight of Protestants to England and Northern Ireland, eventually more than halving, into an insignificant minority, the Protestant share of the Irish state’s population; that was viewed as easing the tensions that had so embittered the Irish civil war.

It is therefore unsurprising that further “unmixing” was seen by the allies in World War II as vital to ensuring peace in the post-war world. In a statement later echoed by Franklin Roosevelt, Winston Churchill made this explicit in 1944, telling the House of Commons he was “not alarmed by the prospect of the disentanglement of populations, nor even by these large transferences, which are more possible in modern conditions than they ever were before”.

The immediate effect, endorsed as part of the Potsdam Agreements and implemented as soon as the war ended, was the brutal expulsion from central and eastern Europe of 12 million ethnic Germans whose families had lived in those regions for centuries. Stripped of their nationality and possessions, then forcibly deported to a war-devastated Germany, the refugees – who received very little by way of assistance – gradually merged into German society, though the scars took decades to heal.

Even more traumatic was the movement in 1947 of 18 million people between India and the newly formed state of Pakistan.

As Indian novelist Alok Bhalla put it, India’s declaration of independence triggered the subcontinent’s sudden descent into “a bestial world of hatred, rage, self-interest and frenzy”, with Lord Ismay, who witnessed the process, later writing that “the frontier between India and Pakistan was to see more tragedy than any frontier conceived before or since”. Yet in the subcontinent too, and especially in India, the integration of refugees proceeded to the point where little now separates their descendants from those of the native born.

All that formed the context in which the planned partition of Palestine was to occur. The 1937 Peel Commission, which initially proposed partition, had recommended a mandatory population exchange but the entire issue was ignored in UN Resolution 181 that was supposed to govern the creation of the two new states.

When a majority of the UN General Assembly endorsed that resolution on November 29, 1947, the major Zionist forces reluctantly accepted the proposed partition, despite it being vastly unfavourable to them. But the Arab states not only rejected the plan, they launched what the Arab League described as “a war of extermination” whose aim was to “erase (Palestine’s Jewish population) from the face of the earth”. Nor did the fighting give any reason to doubt that was the Arabs’ goal.

At least until late May 1948, Jewish prisoners were invariably slaughtered. In one instance, 77 Jewish civilians were burned alive after a medical convey was captured; in another, soldiers who had surrendered were castrated before being shot; in yet another, death came by public decapitation. And even after the Arab armies declared they would abide by the Geneva Convention, Jewish prisoners were regularly murdered on the spot.

While those atrocities continued a longstanding pattern of barbarism, they also reflected the conviction that unrestrained terror would “push the Jews into the sea”, as Izzedin Shawa, who represented the Arab High Committee, put it.

History/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

A crucial element of that strategy was to use civilian militias in the territory’s 450 Arab villages to ambush, encircle and destroy Jewish forces, as they did in the conflict’s first three months.

It was to reduce that risk that the Haganah – the predecessor of the Israel Defence Force – adopted the Dalet plan in March 1948 that ordered the evacuation of those “hostile” Arab villages, notably in the surrounds of Jerusalem, that posed a direct threat of encirclement. The implementation of its criteria for clearing villages was inevitably imperfect, but the Dalet plan neither sought nor was the primary cause of the massive outflow of Arab refugees that was well under way before it came into effect.

Nor was the scale of the outflow much influenced by the massacres committed by Irgun and Lehi – small Jewish militias that had broken away from the Haganah – which did not loom large in a prolonged, extremely violent, conflict that also displaced a very high proportion of the Jewish population.

Rather, three factors were mainly involved. First, the Muslim authorities, led by the rector of Cairo’s Al Azhar Mosque, instructed the faithful to “temporarily leave the territory, so that our warriors can freely undertake their task of extermination”.

Second, believing that the war would be short-lived and that they could soon return without having to incur its risks, the Arab elites fled immediately, leaving the Arab population leaderless, disoriented and demoralised, especially once the Jewish forces gained the upper hand.

Third and last, as Benny Morris, a harsh critic of Israel, stresses in his widely cited study of the Palestinian exodus, “knowing what the Arabs had done to the Jews, the Arabs were terrified the Jews would, once they could, do it to them”.

Seen in that perspective, the exodus was little different from the fear-ridden flights of civilians discussed above. There was, however, one immensely significant difference: having precipitated the creation of a pool of 700,000 Palestinian refugees, the Arab states refused to absorb them.

Rather, they used their clout in the UN to establish the UN Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees, which became a bloated, grant-funded bureaucracy whose survival depended on endlessly perpetuating the Palestinians’ refugee status.

In entrenching the problem, the UN was merely doing the bidding of the Arab states, which increasingly relied on the issue of Palestine to convert popular anger at their abject failures into rage against Israel and the West. Terminally corrupt, manifestly incapable of economic and social development, the Arab kleptocracies elevated Jew-hatred into the opium of the people – and empowered the Islamist fanaticism that has wreaked so much harm worldwide.

Nor did it end there. Fanning the flames of anti-Semitism, the Arab states proceeded to expel, or force the departure of, 800,000 Jews who had lived in the Arab lands for millennia, taking away their nationality, expropriating their assets and forbidding them from ever returning to the place of their birth. Those Jews were, however painfully, integrated into Israel; the Palestinian refugees, in contrast, remained isolated, subsisting mainly on welfare, rejected by countries that claimed to be their greatest friends. Thus was born the myth of the Nakba.

That vast population movements have inflicted enormous costs on those who have been ousted from their homes is undeniable. Nor have the tragedies ended: without a murmur from the Arab states, 400,000 Palestinians were expelled from Kuwait after the first Gulf War, in retaliation for the Palestine Liberation Organisation’s support of Saddam Hussein. More recently, Myanmar has expelled 1.2 million Rohingya.

But the greatest tragedy associated with the plight of the Palestinians is not the loss of a homeland; over the past century, that has been the fate of tens of millions. Rather, it is the refusal to look forward rather than always looking back, an attitude encapsulated in the slogan “from the river to the sea”.

That has suited the Arab leaders, but it has condemned ordinary Palestinians to endless misery and perpetual war. Until that changes, the future will be a constant repetition of a blood-soaked past

“VISIT OF H.R.H. PRINCESS MARY AND THE EARL OF HARWOOD. MARCH 1934. PRINCESS MARY, THE EARL OF HARWOOD, AND THE GRAND MUFTI, ETC. AT THE MOSQUE EL-AKSA [I.E., AL-AQSA IN JERUSALEM].” LIBRARY OF CONGRESS, LC-M33- 4221.

“VISIT OF H.R.H. PRINCESS MARY AND THE EARL OF HARWOOD. MARCH 1934. PRINCESS MARY, THE EARL OF HARWOOD, AND THE GRAND MUFTI, ETC. AT THE MOSQUE EL-AKSA [I.E., AL-AQSA IN JERUSALEM].” LIBRARY OF CONGRESS, LC-M33- 4221.

3 Comments