We condemn explicit anti-semitism but tolerate coded forms

The arrest of Brendan Koschel, a speaker at the Sydney’s anti-immigration March for Australia on Australia Day who described Jews as “the greatest enemy to this nation” was rightly condemned. Such statements are plainly antisemitic and sit outside the bounds of legitimate political expression. Few would argue otherwise. The speed and clarity of the response reflect a broadly shared moral consensus: explicit hatred of Jews is unacceptable and dangerous.

What is less settled is how society responds when similar animus appears in more indirect, politically coded forms. The case invites a broader examination of consistency – of whether antisemitism is being judged by its substance or merely by the vocabulary through which it is expressed.

There is no question that Palestinians have endured profound and ongoing suffering. The devastation in Gaza, mass civilian death, displacement, and the long history of occupation and statelessness demand serious moral attention. Anger, grief, and protest in response to these realities are understandable, and often justified. Acknowledging Palestinian suffering is not a concession; it is a moral necessity.

Yet since October 7, this moral urgency has unfolded alongside a striking rise in hostility directed at Jews well beyond the scope of political critique. Synagogues and Jewish schools have been vandalised. Jewish businesses have been targeted for boycotts based on ownership rather than conduct. Individuals have been harassed, doxed, or pressured to publicly renounce Israel as a condition of social or professional acceptance. These acts are widely acknowledged as regrettable, but they are often treated as peripheral to the movement that surrounds them, rather than as evidence of a deeper moral asymmetry.

That asymmetry becomes clearer when language is examined more closely. Explicit statements condemning “Jews” as a collective are swiftly identified as racist and, in some cases, criminal. By contrast, sweeping denunciations of “Zionists” are frequently treated as legitimate political speech, even when they rely on imagery of disease, conspiracy, or collective guilt.

This distinction matters because “Zionist” is not an abstract or neutral category. In practice, it commonly refers to Jews who support the existence of a Jewish homeland – a position held by a substantial majority of Jewish people in Australia. Surveys consistently indicate that around 80 per cent of Australian Jews identify, in some form, as Zionist. As a result, hostility directed at “Zionists” often functions as hostility toward Jews as a group, translated into a more socially acceptable register. For more on this, see below, “Looking for the good Jews”.

Those who use such rhetoric often insist that they oppose only an ideology, not a people. That claim deserves to be taken seriously. Criticism of Israel – of its government, its military conduct, and its laws – is legitimate and necessary. Opposition to Zionism as a political project is not, in itself, antisemitic. Jewish political opinion is diverse, and many Jews themselves are critical of Zionism in some or all its forms. Israelis are themselves politically divided

The problem arises when this distinction collapses in practice. When Zionists are described as uniquely evil, conspiratorial, or beyond moral consideration, the language begins to mirror longstanding antisemitic tropes. The shift is not always conscious or malicious, but it is real. What would be immediately recognised as hate speech if applied to Jews directly is often defended when routed through political terminology.

This pattern is reinforced by the dynamics of contemporary public discourse. Slogans such as “from the river to the sea,” “globalize the intifada,” and “death to the IDF” circulate widely, in part because they are rhetorically efficient and algorithmically rewarded. They compress history into chant, complexity into certainty. Yet these slogans are also widely heard—by Jews and Israelis—as eliminationist in implication. They gesture toward the disappearance of Israel, invoke campaigns associated with violence against civilians, or endorse the killing of a collective. Comparable language directed at other groups would not be treated as permissible political speech.

Here again, the double standard is evident. A far-right speaker who names Jews directly is prosecuted and publicly shunned. More educated or progressive actors, using different language to express closely related ideas, face little scrutiny. In some cultural and institutional spaces, their rhetoric is actively celebrated.

This uneven moral landscape is sustained by a broader condition of moral capture. In activist environments shaped by social media, intensity is rewarded, hesitation penalised. Historical complexity gives way to moral theatre; political literacy is displaced by symbolic alignment. Once captured, movements become resistant to self-critique. Harm that flows from their rhetoric—such as the intimidation of Jews with no connection to Israeli policy—is reframed as incidental, or simply ignored.

The result is not the elimination of antisemitism, but its adaptation. It becomes more fluent, more respectable, more compatible with prevailing moral fashions. Speech-policing approaches that focus on the crudest expressions may satisfy the desire to be seen to act, but they leave this refined version largely untouched.

The Koschel case thus illustrates a deeper problem. By punishing explicit hatred while tolerating its coded forms, society draws a moral line based on style rather than substance. Prejudice is not challenged; it is merely taught to speak a different language.

A society genuinely committed to opposing antisemitism would need to confront both its vulgar and its sophisticated manifestations. That means applying the same moral standards to hatred expressed from a rally stage and to hatred embedded in politically sanctioned rhetoric. Without that consistency, condemnation becomes selective—and antisemitism endures, renamed but intact.

Coda: On Consistency

What ultimately emerges from this discussion is not a dispute about free speech or political passion, but a question of moral consistency. Antisemitism is widely condemned when it appears in its most explicit and vulgar forms. When it reappears in coded, politicised, or culturally fashionable language, it is often reclassified as critique and exempted from scrutiny.

This distinction rests on vocabulary rather than substance. Hatred expressed without euphemism is punished; hatred expressed through politically approved categories is tolerated, and at times endorsed. The result is not a reduction in prejudice, but its translation into more socially acceptable forms.

Such selectivity undermines the very principles it claims to defend. If collective blame, dehumanisation, and eliminationist implication are wrong, they are wrong regardless of the speaker’s ideology or the language used to convey them. Moral seriousness requires applying the same standards across contexts, rather than adjusting them to fit cultural or political comfort.

A society that confronts antisemitism only when it is crude teaches a damaging lesson: that prejudice is unacceptable only when it is unsophisticated. In doing so, it leaves itself vulnerable to the more durable and corrosive versions—those that pass as conscience, activism, or moral clarity.

Consistency is not censorship. It is the refusal to let hatred rebrand itself as virtue.

Looking for the “good Jews”

An extract from Moral capture, conditional empathy and the failure of shock

In This Is What It Looks Like, we wrote: “… antisemitism does not arrive announcing itself. It seeps. It jokes. It chants. It flatters those who believe they are on the right side of history, until history arrives and asks what they tolerated in its name”.

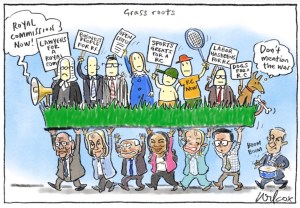

One of those jokes landed, flatly, on January 7 when the otherwise circumspect Age and Sydney Morning Herald published a caricature drawn by the award-winning cartoonist Cathy Wilcox. It presented those calling for a forthcoming royal commission into antisemitism as naïve participants in a hierarchy of manipulation. At the surface were the petitioners themselves; beneath them senior Coalition figures – Sussan Ley, Jacinta Nampijinpa Price, John Howard, David Littleproud – alongside Rupert Murdoch and Jillian Siegel, lawyer, businesswoman and Australia’s Special Envoy to Combat Antisemitism; and behind them all, setting the rhythm, Israel’s prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu. Each layer marched to a beat not its own.

Critics argued that the image revived a familiar and corrosive trope: the suggestion of hidden Jewish influence directing political life from the shadows. The cartoon, titled Grass roots, depicts a cluster of foolish-looking figures demanding a royal commission. They are presumably meant to represent the families of the dead, as well as lawyers, judges, business leaders and sporting figures who had urged government action long before the Prime Minister concluded that continued indifference might stain his legacy. When he finally announced a royal commission—expanded, without explanation, to include the elastic phrase “social cohesion”—no journalist paused to ask what that addition was meant to clarify.

In the drawing, a dog stands among these Australians, holding a placard and thinking, “Don’t mention the war.” The grass beneath their feet is supported by a menacing cast: and stock villains of the anti-Zionist imagination. The implication is unmistakable: that the pleas of grieving families and prominent citizens are neither organic nor sincere, but choreographed – another performance conducted from afar.

That implication did not arise in isolation. Across social and mainstream media, many progressives called for Jillian Segal to be removed and her report rejected out of hand. Others elevated Jewish critics of the war, of Zionism, or of Netanyahu as moral exemplars – “good Jews,” “some Jews tell the truth” – as if Jewish legitimacy were contingent on ideological alignment. Some wrote openly that Jews, “for their numbers,” exercised excessive influence. One circulating meme complained, “We didn’t vote for a Zionist voice”, whilst other posts informed their echo chamber that Chabad Bondi, a branch of the global Jewish outreach organisation, which had organised the Hanukkah gathering on the fateful Sunday evening and also the local commemorations for the victims (and later, the tribute at the Sydney Opera House) was but another tentacle of the sinister and uber-influential Jewish Lobby. Some of the most incongruous postings have been of ultra Orthodox Jews – Haredim – with signs condemning the Gaza war and Zionism, as if to say these are the authentic, “good” Jews. Some footage actually shows Haredim protesting against the Israeli government’s efforts to conscript exempt yeshiva students into the IDF – but, as they say, every picture tells a story.

Running beneath this was a persistent misconception. Judaism was treated as a religion, detachable and voluntary, rather than as an ethnoreligious identity shaped by lineage, memory and shared fate. Jews were asked not simply to oppose Israeli policy but to renounce their “homeland,” their inheritance, their sense of collective belonging. Census figures were deployed to minimise Jewish presence, overlooking the fact that many Jews, with Germany in the 1930s still in mind, remain reluctant to advertise religious affiliation. Genealogical platforms tell a different story: the number of people who discover Jewish ancestry far exceeds those who publicly profess the faith.

Another factor further clouds understanding. Jews are rarely dogmatically regarded as part of what Australians loosely call our “multicultural” society – a variegated demographic more often reserved for the post–White Australia waves of migration – communities that are visibly non-European or culturally distinct. Jews slipped beneath that radar. Many arrived well before the Second World War, and those who came before and after tended to integrate, to go mainstream, to succeed, and therefore not to stand out.

As a result, Jews were quietly folded into an older Judeo-Christian demographic, grouped alongside Protestants and Catholics as part of the cultural furniture rather than recognised as a minority with a distinct history and vulnerability. In most urban, and even regional settings, many Australians would be unaware that Jewish families live among them at all. At the same time, a surprising number of people carry Jewish ancestry several generations back, or are connected through marriage or descent, without regarding this as identity in any conscious way.

This invisibility cuts both ways. It has allowed Jews to belong without friction, but it has also made Jewishness strangely abstract – easy to misclassify as belief rather than continuity, easy to overlook as lived experience, and easy, when political passions rise, to treat as conditional.

Here the paradox sharpens, particularly among progressives. There is genuine respect for Indigenous Australians’ reverence for history, genealogy and Country: an understanding that identity is inherited as much as chosen, that land carries memory and obligation across generations. Yet the Jewish connection to Zion is denied that same conceptual dignity. What is recognised as ancestral continuity in one case is dismissed in the other as theology, nationalism or ideology.

The inconsistency is telling. Jewish attachment to place is stripped of its historical depth and cultural persistence, judged by standards not applied elsewhere. In that light, the cartoon does more than offend. It gives visual form to a deeper habit of thought: one that sorts Jews into acceptable and unacceptable categories, organic grief and foreign orchestration, legitimate belonging and suspect attachment- depending on who is being asked to explain themselves, and to whom.

All of this helps to explain the dangerous and disturbing upsurge in antisemitism over the past two years and earlier.

The Bondi massacre did not invent anti-Semitism in Australia; it exposed a system already bent, quietly, against seeing it. Two recent articles in The Australian show in complementary ways two faces of the same failure: one structural, one intimate. On the one hand, Professor Timothy Lynch diagnoses the intellectual and institutional blindness that allows hatred to incubate unchecked; on the other, author Lee Kofman shows the personal toll when grief itself is made conditional on passing someone else’s moral purity test. Together, they reveal a society in which moral frameworks have become cages rather than guides.

For decades, Australian multiculturalism has performed a delicate contortion: apologising for its own history while demanding loyalty from newcomers. Original British settlement is framed as a sin; multiethnic immigration is a progressive corrective. The paradox, Lynch notes, is that the very order migrants join is simultaneously denigrated by the leaders they are expected to trust. Within this structure, Jews occupy an uncomfortable space: electorally negligible, culturally visible, historically persecuted, yet paradoxically recoded as white and colonial. Zionism – a project of survival and refuge – is reframed as a form of imperial wrongdoing, while other nationalisms pass without scrutiny. Anti-Semitism, filtered through progressive identity politics, becomes an exception to the very rules designed to prevent harm.

Bondi rendered these abstract asymmetries concrete. The massacre forced recognition that anti-Semitism, once dismissed as campus rhetoric or aestheticised resistance, could and would become lethal.

Author’s note …

This opinion piece is one of several on the attitudes of progressives towards the Israel, Palestine and the Gaza war.

The first is Moral capture, conditional empathy and the failure of shock, a discussion on why erstwhile liberal, humanistic, progressive people from all walks of life have been caught up in what can be without subtly described as that anti-Israel machinery Shaping facts to feelings – debating intellectual dishonesty– regarding the Gaza war, intellectual dishonesty is everywhere, on both sides of the divide, magnified by mainstream and social media’s hunger for moral simplicity and viral outrage. Standing on the high moral ground is hard work! discusses the issues of free speech and “cancellation”, and boycotts with regard to the recent self-implosion of the Adelaide Writers’ Festival, one of the country’s oldest and most revered.

There are moments when public argument stops being a search for truth and becomes a test of belonging. Facts are no longer weighed so much as auditioned; empathy is rationed; moral language hardens into a badge system, issued and revoked according to rules everyone seems to know but few are willing to articulate. One learns quickly where the trip-wires are, which sympathies are permitted, which questions are suspect, and how easily tone can outweigh substance.

What interests me here is not the quarrel itself – names, borders, histories—but the habits of mind it exposes. The ease with which conviction can slide into choreography. The way intellectual honesty is praised in the abstract and punished in practice. The curious transformation of empathy from a human reflex into a conditional licence, granted only after the correct declarations have been made.

Across these pieces I circle the same uneasy terrain: the shaping of facts to fit feelings; the capture of moral language by ideological gravity; the performance of righteousness as both shield and weapon. Cultural spaces that once prided themselves on curiosity begin to resemble courts, where innocence and guilt are presumed in advance and the labour lies not in thinking, but in signalling.

This is not an argument against passion, nor a plea for bloodless neutrality. It is, rather, a meditation on how quickly moral seriousness curdles into moral certainty – and how much intellectual work is required to stand on what we like to call the high ground without mistaking altitude for clarity.

The position of In That Howling Infinite with regard to Palestine, Israel and the Gaza war is neither declarative nor devotional; it is diagnostic. Inclined – by background, sensibility, and experience – to hold multiple truths in tension, to see, as the song has it, the whole of the moon. It is less interested in arriving at purity than in resisting moral monoculture and the consolations of certainty. That disposition does not claim wisdom; it claims only a refusal to outsource judgment or to accept unanimity as a proxy for truth.

On Zionism, it treats it not as a slogan but as a historical fact with moral weight: the assertion – hard-won, contingent, imperfect – that Jews are entitled to collective political existence on the same terms as other peoples. According to this definition, this blog is Zionist. It is not interested in laundering Israeli policy, still less in romanticising state power, but rejects the sleight of hand by which Israel’s existence is transformed from a political reality into a metaphysical crime. Zionism is not sacred, but its delegitimisation is revealing – because it demands from Jews what is demanded of no other nation: justification for being.

On anti-Zionism, it has been unsparing. It sees it not as “criticism of Israel” (which you regard as both legitimate and necessary) but as a categorical refusal to accept Jewish collective self-determination. What troubles it most is not its anger but its certainty: its moral absolutism, its indifference to history, its willingness to borrow the language of justice to license erasure. It is attentive to how anti-Zionism recycles older antisemitic patterns – collectivisation of guilt, inversion of victimhood, and the portrayal of Jews as uniquely malignant actors – while insisting, with studied innocence, that none of this concerns Jews at all. If not outright antisemitism, the line separating it from anti-Zionism is wafer—thin, and too often crosses over.

The interest in moral capture is analytical rather than accusatory. It is not arguing that writers, academics, or institutions are malicious; rather, it argues that they have become intellectually narrowed by the desire to belong to the “right side of history.” Moral capture explains how good intentions curdle into dogma, how solidarity becomes performative, and how the fear of social exile replaces the discipline of thought. It accounts for the strange phenomenon whereby intelligent people outsource their moral judgment to slogans, and experience constraint not as an intolerable injury to the self.

The Adelaide Writers’ Festival affair iss seen not primarily about Randa Abdel-Fattah, nor even about free speech. It is a case study in institutional failure and cultural self-deception. The mass withdrawals are viewed not as acts of courage or principle but as gestures of affiliation – ritualised displays of virtue by people largely untouched by the substance of the dispute. What is disturbing is the asymmetry: the speed with which a festival collapsed to defend eliminationist rhetoric, and the silence that greeted the doxxing, intimidation, and quiet cancellation of Jewish writers and artists. Adelaide did not fall because standards were enforced, but because those standards were applied selectively and then disowned at the first sign of reputational discomfort.

Running through all of this is a consistent stance: a resistance to moral theatre, an impatience with historical amnesia, and a belief that intellectual honesty requires limits – on language, on fantasy, and on the indulgent belief that one’s own righteousness exempts one from consequence.

We are not asking culture to choose sides; you are asking it to recover judgment

.See in In That Howling Infinite, A Political World – Thoughts and Themes, and A Middle East Miscellany. and also: This Is What It Looks Like, “You want it darker?” … Gaza and the devil that never went away … , How the jihadi tail wags the leftist dog, The Shoah and America’s Shame – Ken Burns’ sorrowful masterpiece, and Little Sir Hugh – Old England’s Jewish Question

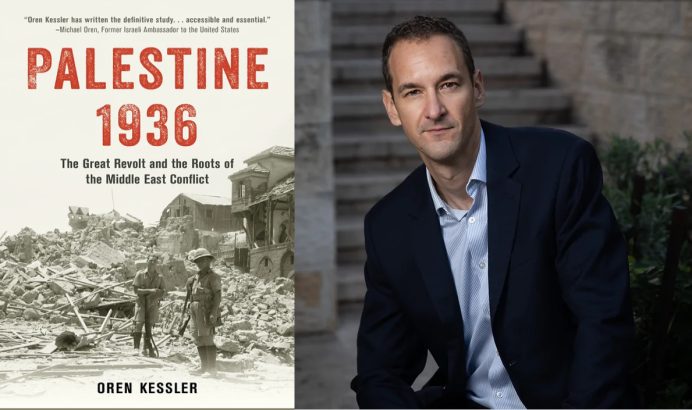

“VISIT OF H.R.H. PRINCESS MARY AND THE EARL OF HARWOOD. MARCH 1934. PRINCESS MARY, THE EARL OF HARWOOD, AND THE GRAND MUFTI, ETC. AT THE MOSQUE EL-AKSA [I.E., AL-AQSA IN JERUSALEM].” LIBRARY OF CONGRESS, LC-M33- 4221.

“VISIT OF H.R.H. PRINCESS MARY AND THE EARL OF HARWOOD. MARCH 1934. PRINCESS MARY, THE EARL OF HARWOOD, AND THE GRAND MUFTI, ETC. AT THE MOSQUE EL-AKSA [I.E., AL-AQSA IN JERUSALEM].” LIBRARY OF CONGRESS, LC-M33- 4221.